Полная версия

Britain in the Middle Ages: An Archaeological History

So far, evidence for the vigorous trade in Middle Saxon southern Britain comes from coins and other metal objects, from Ipswich Ware and from imported pottery such as Tating Ware; but what were the other products being traded? I have already mentioned wool in the Thames Valley, and there are good indications that wool and indeed finished cloth were important commodities produced and manufactured in rural British sites. In modern terms the farmers of Middle Saxon England were ‘adding value’ in a significant fashion to their basic product, wool. The evidence for this comes from several sites, including Shakenoak in the Upper Thames, where sceattas (those early silver Saxon coins) were found associated with loomweights. Clear evidence that the trade was not always just for money, and involved the exchange of imported goods as well, comes from the Anglo-Saxon village at West Stow in the sandy Breckland of north Suffolk.31 What makes West Stow so interesting is its early date. Middle Saxon Ipswich Ware only makes its appearance in the village’s final phase, and it declines in importance during the seventh century. During this time families moved off the sandy knoll where the original settlement was positioned, probably towards the church of the existing village of West Stow nearby.

West Stow was a pioneering excavation by Stanley West, who successfully achieved what we are trying to do at Flag Fen in Peterborough. He excavated the village in 1965–72 and then set about reconstructing it, using authentic techniques. It became a major visitor attraction, and is growing in popularity year on year. Somehow he managed to obtain support from the local authorities, and this has made all the difference to the operation. I go there regularly in the springtime, and having lived with sticky, wet Fenland clay all winter, it makes a wonderful change to stand on warm, dry sand and listen to the wind in the Scots pines, or watch siskins feed on alder cones in the damp valley at the bottom of the knoll. It can be a magical spot.32

The excavations at West Stow produced a large number of finds, many of which were metal, and although this is a site where coins are rare because of its early date, it is hard not to imagine that had it been systematically worked over by competent detectorists, it would have proved very ‘productive’ – to reuse that slightly distasteful term. So was it a trading centre of some sort? A quick glance through the list of finds might suggest that it was. No fewer than thirteen buildings produced fragments of querns made from a volcanic lava which occurs in central Europe. There was abundant evidence for weaving, not just the familiar fired-clay loomweights, but an iron ‘weaving batten’ – a tool used to beat down and compact the threads. Trade was well under way by the late sixth century, when pottery made by an important group of regional workshops based around Lackford appears at West Stow. Other objects, such as the fine bronze brooches, together with glass and amber beads, found on bodies in the cemetery, suggest that many of the inhabitants could afford exotic finery. In the late phases trade with the outside world was expanding. We see this not just in the quantities of Ipswich Ware being brought to the site, but in very upmarket and unusual things, such as a cowrie shell and two silver miniature shields, probably worn around the neck as pendants.

There is nothing at West Stow to suggest that the inhabitants had access to, or controlled, any unusual resource such as salt or ore. Stanley West is convinced that this prosperous community earned its wealth by farming and by selling the surpluses it produced, such as wool (cloth), hides, meat and so forth. It’s quite possible that they sold slaves as well – an unpleasant trade for which there is good archaeological and documentary evidence in Saxon times. It’s hard not to conclude that it was this pattern of trading essentially rural products that was taken forward into the eighth and ninth centuries. In other words, by the mid-seventh century exchange and commerce were an integral part of rural life, and provided the goods that were traded from the emporia and ‘productive’ sites – many of which would have housed people who were also making and producing things.

If the economy at West Stow seems to have been mainly centred around wool, cloth and hides, other later sites show signs of greater specialisation. Sometimes the specialised production was encouraged by a local church; in other instances it seems to have been private enterprise by landowners and farmers. I’ve already mentioned Keith Wade’s site at Wicken Bonhunt in Essex, which produced many pig bones, suggesting that it specialised in the production of pork. Very close to where I am currently writing, a group of Fenland sites on the silty banks of tidal creeks surrounding the Wash were most probably cattle farms specialising in beef.

These cattle stations, as they might be called in Australia, were first revealed by Bob Sylvester and his colleagues of the Fenland Survey around 1984 when they spotted scatters of Ipswich Ware lying on the surface (being dark, it shows up quite well in dry weather, when the silty soil turns pale).33 Contrary to popular opinion, the Fens are not all boggy areas, and the so-called ‘Marshland’ soils around the Wash are naturally well-drained; they mainly consist of Iron Age tidal silts, which are actually quite porous because the individual particles of silt are halfway in size between sand and clay, so there are spaces for the water to pass through. This silty soil is very fertile – my vegetable garden grows sprouting broccoli the size of small trees – and it also makes excellent cattle pasture, being sufficiently dry on the surface to prevent foot problems in most animals.

Bob’s work was particularly important because it shows how archaeology can be used to extend and amplify the historical record. It has long been known from documentary sources that the silty marshland west of King’s Lynn was a very wealthy area. This wealth derived mainly from livestock, especially sheep, but salt was also extracted from the creeks around the Wash, and the proximity of the prosperous and growing port of King’s Lynn certainly aided this process. If we rely on documentary sources alone, it would seem that the wealth of the region began to increase from the time of Domesday (1086) until the thirteenth century, by when it was a very prosperous area indeed. There were, however, no reasons to suppose that Marshland was particularly important in Saxon times until Bob Sylvester and Andrew Rogerson started methodically to survey the Norfolk parish of Terrington St Clement.

I first met Andrew when I was working at North Elmham in 1970, and I knew him to be an imaginative but essentially hard-nosed specialist in early medieval archaeology. He was never one to jump onto bandwagons, and he scrupulously avoided exaggerated claims, which is why I well remember his huge enthusiasm about discoveries at a site named Hay Green, just outside the village. It was the scale that was so extraordinary. Andrew and Bob revealed a vast scatter of about a thousand Ipswich Ware sherds along the banks of an extinct tidal creek, or roddon. From the air you can see a network of pale, silt-filled roddons snaking their way across the landscape. At ground level they show up as low silty mounds which would have been where Middle Saxon communities placed their homes, their farms and their stockyards. This was the land that rarely flooded, even after the heaviest rains.

Bob and Andrew found Ipswich Ware across thirteen fields, covering about seven hectares (over seventeen acres) and extending along the roddon for a distance of 1.5 kilometres. This was a truly massive spread, but what was even more interesting was that Hay Green was almost entirely Middle Saxon – there was only very little later material, probably because by then Late Saxon and Norman settlement had moved to Terrington, just north of the fine medieval church. On the face of it, this might suggest that the life of the Middle Saxon farming settlement was short and sharp. The scatter was large, but it was difficult to say any more about it without digging some selective holes. This happened a few years later, when some of the most important sites revealed in the Fenland Survey were given a closer look.34

It would now seem that Hay Green was not alone. The Fenland Survey revealed six other comparable sites that were evenly spaced out across the Marshland silts. This arrangement strongly suggested that these farms or settlements were part of a Middle Saxon planned development. It was also suggested, in line with what we know happened somewhat later, that the individual farms or settlements could have been linked to upland estates on the higher ground of ‘mainland’ Norfolk, to the east.

Like all good surveys, the ‘field-walking’ was more than just a pot-pick-up.* Metal detectors were also used, but to everyone’s surprise they failed to find significant quantities of coins (sceattas) or any other metalwork. This was most peculiar, given the huge quantities of quite high-quality pottery. The surface survey also revealed a number of animal bones, many of which had been burnt. It was all rather mysterious. Everyone was agreed: trenches must be dug.

They decided to excavate at Hay Green and two other sites of the remaining six. All three sites produced a number of archaeological features, which was a relief to the excavators, who had feared that most would have been destroyed by modern farming. Big ditches had been dug along the roddon, and at Hay Green these ended in a series of large pits which were filled with quantities of animal bone and debris. Much of the animal bone showed obvious signs of butchery (butchery marks are now well-studied in archaeology), and it was clear that this had happened in situ. It therefore appears that meat was being exported from the site as joints or sides, rather than ‘on the hoof’.

So far no clear evidence for settlement has been found, but this probably reflects the fact that larger, ‘open area’ excavation was not possible. The excavators believe it is likely that the six sites were only occupied in the summer months, when the grazing was at its best and the risk of flooding was minimal. So this livestock enterprise represents the planned exploitation of an underused natural resource at a time when conventional history might have us believe that the economy was still largely underdeveloped. It shows not only that these farmers had the wealth to buy in quantities of pottery, but that their products could be distributed efficiently to markets that were sufficiently rich to justify such a large-scale enterprise. The more we look at the Middle Saxon period in southern Britain, the more we realise that it was about far, far more than mere subsistence farming.

Ben Palmer is of the opinion that some rural sites may have had access to traded goods because of their location close to one or more roads or rivers. Laying aside the fact that the same can be said for most settlements, he points to rural sites such as Lake End Road near Maidenhead which do not seem to have anything special to offer, but which contain traded goods. This site lies close to the Thames, and has produced imported pottery, lava quernstones and Ipswich Ware from filled-in pits. So far, and despite extensive excavation, there is no clear evidence for metalwork or for permanent settlement. Whoever frequented this rather enigmatic site could also ‘tap in’ to passing trade. That is the theory. Palmer also suggests a nearby Thames-side site at Yarnton in Oxfordshire as a place that benefited from the passing trade along the river. But in this particular case I think it was rather more than that.

I first came across Gill Hey’s complex multi-period project at Yarnton when I found my wife Maisie, a specialist in ancient woodworking, standing at the kitchen sink examining a waterlogged Bronze Age notched-log ladder. She had collected it the week before from the store at the Oxford Archaeological Unit, and was working indoors because it was bitterly cold in our barn, where she normally did such things. The ladder had been excavated by Gill Hey at Yarnton, which had also revealed a large Iron Age community, Roman settlement, Early Saxon and now Middle and Late Saxon occupation. Most of these important sites were later destroyed, either by gravel quarries or road schemes.

Maisie had known Gill as a student when Gill was doing research into Peruvian pottery, of all things. Subsequently she quit South America for the Thames Valley and began her remarkable project at Yarnton, which I first mentioned in Seahenge, my autobiographical book on Bronze Age religion.35 Yarnton is that rare thing, a large-scale excavation which also happens to be a thoroughgoing landscape project.

Gill recently published her report on the Saxon period at Yarnton.36 Yarnton lies on the very edge of the gravel terrace, on land that would have been just outside the limit of the river’s winter floodplain. This location ‘at the edge’, as it were, was deliberately chosen both in the Bronze and Iron Ages, as in Saxon and medieval times. The Thames floodplain is dressed with a thin layer of flood clay, known as alluvium, every time the river is in spate. This material is very fine, and is rich in natural fertilisers. As a result the grass gets away to a very good start in the spring, and gives young lambs and calves what farmers refer to as ‘a good bite’. In the past, before we learned how to ignore traditional ways of doing things, this land was never ploughed. Today it is, and surprise, surprise, the soil washes away and clogs up streams and drainage dykes.

Good arable land was to be found on the light, well-drained gravel soils around the villages that clustered at the edge of the floodplain, and up the gentle slopes of the valley sides to the north of them. Beyond this arable belt was another landscape of rough pasture, woodland and scrub. This was where most of the building material for houses and fences was grown. It was also a good ‘emergency reserve’ of fodder in wintertime and in very dry summers. Most grazing animals are quite happy to browse (in other words to eat the leaves of trees and shrubs) if grazing is running short – in fact my sheep prefer browsing the young shoots of hawthorn hedges around the fields to the rich Fenland grass at their feet. So Yarnton and the villages around were carefully positioned not just to be safe from flooding, but to exploit their natural surroundings as efficiently as possible.

Yarnton has produced huge quantities of Iron Age and Roman pottery. I can remember being in the finds shed surrounded by trays and trays of pottery stacked up to dry. This is what one would expect of an Iron Age site in the Thames Valley. But archaeology isn’t always predictable. As a general rule of thumb, in areas where pottery is common in the Iron Age, it remains popular in post-Roman times. The converse also applies, so in places like the west Midlands around Cirencester, the Iron Age is almost aceramic – presumably people used basketry and wooden bowls instead – then the usual types of semi-mass-produced Romano-British pottery appear in the Roman period. At the close of the Roman period people revert to their old ways and pottery vanishes from the scene. But at Yarnton, despite the richness of its Iron Age pottery, post-Roman sherds are rare. This is particularly odd given the size and seeming prosperity of the Saxon settlements. These were not pokey, subsistence-style farmsteads clinging onto a blasted hillside somewhere in the mountains, but a thriving and vigorous set of expanding communities in the heart of the pastoral lushness that is the Thames Valley. So what was going on?

Yarnton and other sites around it revealed Early Middle and Late Saxon settlements, yet the total number of pottery fragments found there was just 117, weighing a fraction more than two packets of sugar (actually 2.192 kg). I would have expected something more like a quarter of a tonne, comprising anything from 10–50,000 sherds. We must assume that there isn’t a simple physical reason for the rarity of potsherds, like very acid ground water, which can dissolve shell and other calcareous components of the pottery. So the answer has to be cultural. For some reason the people living in Saxon Yarnton didn’t make or use much pottery. To an archaeologist, and probably only to an archaeologist, that might seem odd. But it isn’t. In fact the decision not to use pottery is perfectly rational, if unusual, because good containers can be made from wood or basketry, and of course birch bark, which we happen to know was used in the Thames Valley in prehistoric times. These organic containers will only survive in waterlogged conditions, where the air needed for fungi and bacteria to break down organic materials is absent. Such containers are durable, they don’t shatter when dropped, and they don’t require complicated technology to make. In fact it’s interesting to note that two probable Iron Age pottery kilns are known from Yarnton. But in Saxon times they wanted none of it, and preferred instead to use local materials such as willow and birch bark that would have grown plentifully nearby. To me, this seems a perfectly reasonable choice.

The pottery that did manage to survive was very interesting, and Gill’s pottery specialist, Paul Blinkhorn, made the most of what little he had to work on.37 Perhaps the most remarkable result actually took very little analysis: the features of the Saxon settlement contained more Iron Age and Roman pottery (3.5 kg) than Saxon. This was material that was lying around on the surface when the Saxon houses were built, ditches were dug and so forth, a strange inversion of what one might normally expect. During the life of the settlement this earlier debris slipped into the various ditches, pits, wells and post-holes, along with fragments of the few contemporary Saxon pots.

The Saxon pottery included nine sherds of Ipswich Ware, and Yarnton is so far the most westerly site to have revealed this early form of mass-produced pottery. Paul Blinkhorn has pioneered a sophisticated form of chemical analysis, known as ICP-AES (or Inductively-Coupled Plasma Atomic Emission Spectroscopy), which has shown that all the Ipswich Ware we currently know about was made from clays occurring in Ipswich. It can therefore be considered a very reliable indicator of Middle Saxon trade. Ipswich Ware was made between about 720 and 850, but was not traded outside East Anglia until about 730. At the height of its popularity it was traded as far north as York and as far south as Kent. Huge quantities have been found in the emporium at London, and it is assumed that Yarnton would have been within its trading area. Recently other sites in the Thames Valley have revealed Ipswich Ware, so it would seem reasonable to suggest that Yarnton was part of this trading network. As at other non-East Anglian sites, the Ipswich Ware from Yarnton included just a few vessels (around seven), the majority of which were large jars that probably originally contained some traded commodity such as salt or oil. It is always a problem, when it comes to pottery, to determine whether the vessels were bought for themselves, or for what they may once have contained.

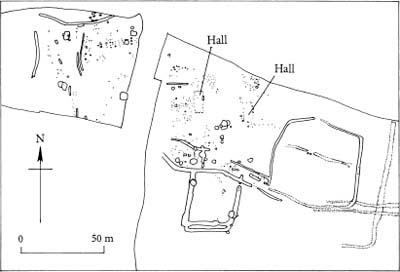

FIG 6 The Middle Saxon settlement in the Thames Valley at Yarnton, Oxfordshire (AD 700–900).

There have been relatively few recent excavations of Middle Saxon settlements, so Gill Hey’s work at Yarnton is most important. A series of radiocarbon dates has indicated that occupation began in the late seventh century and lasted through the ninth (say 700–900). There was occupation in and around Yarnton in the Early Saxon period, but Gill is keen to emphasise the contrast between that and what followed: ‘The contrast between the Early and Middle Saxon settlements at Yarnton is strong. There are radical differences in the size of the settlement area, in the degree of organisation within it, in building type and in the variety of structural remains and other features … but the coherence of the [Middle Saxon] settlement plan suggests that it was organised on this large scale from the beginning.’38

The settlement involved, for the first time, substantial timber buildings in addition to the more traditional building form of the Early Saxon period, the SFB or sunken feature building, which essentially consisted of a single-storey structure with a wooden floor over a cellar-like space beneath.39 This space probably served to keep the floor dry and would have helped the floor joists resist wet-rot.

The large buildings were a series of post-built rectangular halls and their outbuildings, including an impressive circular poultry house. These buildings were set within enclosures that were defined by ditches, and perhaps by hedges too. Gill notes that from the eighth to the tenth centuries the use of space within the settlement became increasingly formalised. She suggests that this may have been a reflection of two things: greater social control and authority, coupled with a growing shortage of land.

The changes visible in the layout of the settlement are mirrored in the surrounding countryside, where analysis of botanical samples suggests that farming was changing quite rapidly. Hay meadows were being laid out, major boundaries between larger holdings were being constructed, and manuring (using manure from farms and settlement) was introduced as a regular part of the farming cycle. Farming, in other words, was becoming more organised and intensive, yet at the same time it was also more diverse, with a greater variety of crops being grown. Technological improvements included the probable introduction of the mouldboard or heavy plough, which allowed soil to be cast to one side to form a true furrow.

The new form of plough was invented sometime in the mid-first millennium AD, and was one of the great unsung technological developments of the early medieval world. Suddenly proper ploughing became possible: the soil was cut, lifted and folded back on itself. This had all sorts of beneficial effects. The top growth of weeds was denied light beneath the surface, and died. Any manure spread on the surface was taken down into the ground, where the earthworms could give it their undivided attention. Earlier, non-mouldboard ploughs were known as ‘ards’ or scratch-ploughs. They were invented in the Near East in the fifth millennium BC, and were most effective if used in two directions, a pattern known as ‘cross-ploughing’. The best British example of the marks left by cross-ploughing with an ard was found below the mound of the South Street long barrow, just outside Avebury in Wiltshire, and dating to the fourth millennium BC.40 I once had the doubtful pleasure of actually using an ard. It was pulled by two oxen, took all my strength and weight to keep it in the ground, and I only managed to make it penetrate about four inches deep. It really was a struggle, despite the fact that the two oxen were remarkably tame and behaved themselves excellently. I concede that ancient farmers would have had generations of skill and practice to guide them, but even so, I found it extraordinarily difficult. These earlier ploughs acted more like a huge hoe or a modern tractor-towed sub-soiler, which simply breaks up and lifts the soil as it passes through. All the effort goes into encountering the soil’s initial friction and resistance; less attention is paid to what happens as the ploughshare passes through. It’s a subtly different way of looking at the problem and the process of ploughing.

This pattern of intensification coupled with new technology is also seen at other Middle Saxon sites in the Thames Valley. It echoes, too, what we saw in the Fens of the Norfolk Marshland – and there are many other examples that show how the Middle Saxon period was one of stability, increasing social control and rapid economic development, at home and abroad. These changes in the countryside were combined with the growth of the first towns and the spread of international trade. It must have been a remarkably dynamic time in which to have lived.

Michael McCormick’s view of early medieval Europe accords well with what we now know about the Middle and Late Saxon period in southern Britain. Increasingly archaeological evidence is revealing this as a time of vigorous change, trade and development, with regular communication over long distances. It seems no exaggeration to say that in the four centuries before the Norman Conquest, Later Saxon southern Britain was very much a part of Europe, and not just as a matter of economic convenience. The ties were also cultural, scholarly and ecclesiastical. Perhaps rather surprisingly, given the fact that William the Conqueror was a Norman with Viking family ties, the close relationship between Saxon England and its Continental neighbours failed to develop much further under him or his offspring. If anything, the Plantagenets and other high medieval monarchs took England in a more insular direction – whatever they might have claimed by way of territory across the Channel.