Полная версия

Britain in the Middle Ages: An Archaeological History

What were these ‘productive’ sites like? Were they towns, administrative centres, trading posts, religious houses, settlements – or what? Here we are confronted with the biggest problem of all: none in Britain has yet been thoroughly or totally excavated. So the short answer is that we don’t know. But some work on the setting of these sites has been done, and of course we do have the non-ferrous metal finds themselves to guide us. As we will see shortly, most are located on rivers or at spots where roads are readily accessible. It’s possible that some ‘productive’ sites were temporary fairs, but so far this has not been demonstrated for certain. Many of the finds – which we must remember are a highly biased selection – compare well with what one might expect to find at a settlement. So it does seem likely that people were actually living at these places.

It is possible to view the growth and development of individual British ‘productive’ sites in two ways. They might have sprung up as trading centres because of their location close to rivers and roads. Prehistorians have found that a safe or ‘neutral’ position at some distance from a large centre of population might help in the establishment of such a place, where trade and exchange could happen with some assurance of security. After a while the trading post would grow as a settlement and soon it would acquire other facilities, such as the provision of justice, administration and financial services – a mint, for example.

But there is another way of looking at the situation. J.D. Richards, basing his remarks on fieldwork he carried out at Cottam, a ‘productive’ site in East Yorkshire, wonders whether we are placing the cart before the horse by putting so much stress on the productiveness of ‘productive’ sites.23 He asks whether, if they had been found by more conventional archaeological techniques, they would simply have been seen as important regional communal centres – rich settlements, in other words. Although he seems at first glance to be taking a less dramatic, and rather more conventional, view of the period, I find his ideas ring archaeologically true. His suggestion is persuasive because it helps to demystify the concept of ‘productive’ sites, which otherwise seem to lack a rationale.

It is not often that I come across an academic paper that excites me so much that its implications keep me awake at night, but it happened recently when I read Ben Palmer’s thoughts on emporia and ‘productive’ sites in southern England.24 It happened to be the first chapter I read in Tim Pestell and Katharina Ulmschneider’s Markets in Early Medieval Europe: Trading and ‘Productive’ Sites, 650–850, a collection of essays that I have already drawn upon quite heavily and that will undoubtedly have a profound effect on the way we think about the archaeology of early medieval Europe for years to come. Palmer’s paper is original because it focuses on what used to be called inter-site (as opposed to intra-site) archaeology. Most archaeologists spend their time wondering how people led their lives or conducted ceremonies on one specific site. This inevitably follows the process of excavation, which is intensely focused and usually has the archaeologist ‘by the throat’ – I speak from personal experience. Plainly one looks at other sites for comparisons and parallels, but that tends to happen very late in the post-excavation period.

Such short-sighted introspection is discouraged if the information is coming from a number of separate places, and when detailed excavation and survey are usually not involved. The result is what the prehistorian Robert Foley termed ‘off-site archaeology’, where one studies what was happening between rather than on sites. This approach helps one to understand both what it was that held the network of sites together, and why the system appeared on the landscape in the first place.25 Ben Palmer’s paper is an excellent example of the genre. He confines his attention to south-eastern England, the main region of rapid economic growth in the Middle Saxon period.

The first impression I had when I read Ben Palmer’s paper was of geographical ‘connectedness’. This paper could never have been written about prehistoric Britain, and it certainly did not resemble anything I knew on the archaeology of the post-Roman ‘Dark Ages’. These periods were simply too remote, and lacked the necessary information. It took just two centuries for that to change. The world he was discussing was a working, functioning trading system. We don’t know whether they had such things, but it would have been possible to compile road maps showing places where one could stay the night, get a meal and find fresh horses. It seems to me that the false emphasis on loot – on coins and ‘productive’ sites – tends to obscure the fact that Middle Saxon southern England was about more than just trade in objects from foreign parts: these networks were also about people living their daily lives – selling their wool, making their clothes and growing their food. We can now discern coherent trading landscapes where we can observe the relationship of the town to the countryside – and how each supported the other. To my eyes this paper showed the first signs of a geography that was recognisably modern.

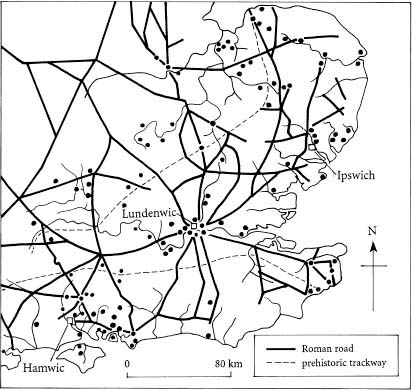

There has been some debate as to whether the three major centres (emporia or wics) at Ipswich, Lundenwic (London) and Hamwic (Southampton) were ‘true’ towns, in the sense that they supported a large population and were self-governed. Pre-Viking York (Eoforwic) is another likely contender for wic status. Personally I’m in little doubt that these settlements were fully urban, as we would understand the term today, because I cannot see how places with such a density of settlement could survive and prosper in any other way. Further, a significant proportion of the population must have spent all their time being merchants or artisans. They would have had little or nothing to do with the production of food from the land.

But I will leave that particular discussion aside, because I’m not sure it’s either relevant or interesting. What matters is that these places are something altogether different from anything that had gone before: not only are they larger and richer, but they are positioned at key points in a much larger network of settlement, trade and communication. It cannot be a coincidence that they are all more or less the same distance apart, and straddle the south-eastern approaches, like the open mouth of a vast trawler net being slowly towed towards the North Sea. The traditional view of wics and emporia is that they were one-offs, isolated and before their time. Ben Palmer describes the old view of them as a failed experiment in kingdom-building. They owed their existence to the fact that they were ‘gateway communities’ that stood on the periphery of the developed core of western Europe, represented by Francia, the Empire of the Franks.

FIG 5 South-eastern England in the Middle Saxon period, showing the location of the three major centres (emporia or wics) at Ipswich, Lundenwic (London) and Hamwic (Southampton). ‘Productive’ sites and other significant settlements or trading centres are shown by dots.

Here I must briefly break off to say a few words about Charlemagne and the Franks. Charlemagne is often seen as the father of modern Europe, and his empire the true ancestor of the European Community. Jacques Le Goff takes a more sceptical view. For him, Charlemagne produced an abortive Europe that nevertheless left behind a legacy.26 This is a view with which most archaeologists would probably agree.

The Franks were a Germanic people who expanded west across the Rhine in the late fifth and sixth centuries, under the command of their remarkable king Clovis (died c.511), to occupy most of central and eastern Gaul (France). This expansion was continued by their greatest emperor, Charles the Great, or Charlemagne (771–814). Under his leadership the Carolingian Empire was to occupy most of western Europe, excepting Spain and southern Italy. Charlemagne, who was barely literate himself, reformed and expanded the power of the Church and encouraged the development of art and letters. While he was in sole charge his empire was stable and very prosperous. The tradition of scholarship was continued by his successors Louis the Pious and Charles the Bald, but the old flair had gone, and Europe now entered a less stable period when political allegiances were shifting. By the mid-tenth century the driving force of the Carolingian Empire shifted towards Germany, with the accession of Otto I in 936.

The traditional view is that the wics and emporia stood at the boundary of the developed core (Francia) and the underdeveloped periphery, represented by Britain and Scandinavia. In today’s politically correct world we would doubtless refer to the latter as ‘developing’ – which the new archaeological evidence would suggest was factually correct too. As in subsequent core/periphery relations between an imperial centre and outlying regions, it was held that the wics and emporia were the places where raw materials were exchanged for luxury goods from Europe. Put cynically, the periphery produced the things that mattered, and received showy trinkets in exchange.

This view of the setting up and operation of wics and emporia was given added weight by scholars such as Richard Hodges, who analysed these processes in the contexts of European macro-economics. He reasoned that trade and exchange only make sense if you look at the whole picture. His approach was anthropological, and rings sort-of true to a prehistorian like myself. I say ‘sort-of’ because there are no such things as permanent, static laws in anthropology, and Hodges’s seminal study of the subject, which appeared in 1989, now seems to me at least somewhat dated and mechanistic, although at the time it deservedly had a huge impact.27 His views on the social and economic forces behind the growth of wics and emporia in the seventh and eighth centuries are still very influential, and are essentially based on the competitive relationship between the governing elites in the various emerging states and kingdoms.

Anthropologists love relationships. They believe that the way humans react to each other is governed by forces other than instinctive or emotional likes or dislikes. So anthropologists hold that a married man will tend to have strained relations with his mother-in-law because she resents the loss of her daughter, and he feels that his wife is reluctant to leave her original family because her mother wants her back. Such competitive relationships have also been found in the world of tribal politics, where family considerations also complicate matters. The competitive nature of the relations between ruling elites was first discussed in detail by the great anthropologist Bronislaw Malinowski in The Argonauts of the Western Pacific (1922). He studied the exchange of gifts between the inhabitants of the Trobriand Islands, and realised that the exchange formed part of a complex system of social obligation known as the Kula cycle. This cycle was based on what anthropologists refer to as ‘Malinowski’s principle of reciprocity’ – a sonorous phrase which suggests that no gift-giving is without some form of motive. As the words imply, each ‘gift’ was actually nothing of the sort, because it carried with it the prospect of something in return: either another gift later, or some form of social obligation. Malinowski also realised that these exchanges encouraged competition between the elites on different islands. So a particularly lavish gift was less a generous donation than an expression of power on the donor’s part.

Malinowski was an extraordinary man who also established the ground rules of anthropological fieldwork. Among other achievements he pioneered the process of structured interviews, which allowed him to compare the responses he received from different people right across the huge island archipelago he studied. Today his approach is seen as ‘functionalist’. In other words he based much of what he observed on common-sense observation and a rather masculine (dare I say it, simplistic) view of human relationships, perhaps summed up by: ‘one good turn deserves another’. Subsequent workers, most famously Margaret Mead in her wonderful book Coming of Age in Samoa (1928), showed that there was a great deal more to human relationships in the Pacific – and of course elsewhere – than could readily be defined by laws of reciprocity alone. Returning to ancient trade and exchange, more recent studies such as The Gift by Marcel Mauss (1950) and Stone Age Economics (1974) by Marshall Sahlins have been far less functionalist than Malinowski; but even so, his fundamental principle still seems to apply.28 Reciprocity and exchange are now seen as organising structures that are about more than the giving of gifts: they underlie most social, economic and administrative processes in both ancient and modern societies.

Archaeologically speaking it is very hard to distinguish between the exchange of gifts and trade, pure and simple, because each involves reciprocity of one form or another. Moreover, where exchange at an elite level happens, it is not unusual to find other, smaller transactions also taking place further down the social ladder. Transactions of this sort do resemble trade, when seen in the archaeological record, because a large variety of objects – even coinage – may be involved.

One useful rule of thumb that can help us define what was going on concerns the nature of the places where transactions took place. Traditionally the emporia and wics have been seen as rather isolated phenomena that contrasted markedly with the not-so-very-prosperous rural settlements that surrounded them. There are signs too that they were laid out by a central authority: for example, streets were arranged on a grid pattern, and many buildings seem to have been erected simultaneously. The finds include exotic items such as wine containers and pottery imported from the area around the Rhine. Taken together, these clues suggest that the wics and emporia were set up by powerful elites to control trade to and from the territories they ruled. The reason they wanted to control the trade was simply to establish a royal monopoly on prestige goods, which they could then use to grease the wheels of power both externally, as regards foreign policy, and internally, by rewarding the loyalty of key families and individuals. In a command economy which was based on the exchange of prestige goods, the control of commerce led naturally to the control of people.

It was believed that the establishment of the wics and emporia by royal patronage did not protect them forever, which is why they began to decline. They lost their central role by, and just after, the end of the eighth century. There was then a gap of about a century, during which time there was effectively no substantial urban presence in Britain. This apparent hiatus coincided with the first period of Viking raids and settlement (we will see that their first raid, on the monastery at Lindisfarne, took place in 793). The next set of major urban foundations were the fortified burhs, which we know for a fact were established by royal command, first as a defensive measure against raids and then as protection from Viking forces present in Britain. I will return to the burhs in the next two chapters, but the important point to make here is that the bulk of them were established in the late eighth and early ninth centuries.

The conventional wisdom on early towns and the separation of the earlier wics and emporia from the later burhs only really makes sense if we can detect good evidence for discontinuity – which in archaeology must always be proved, and never assumed. The idea of discontinuity also subsumes that of abandonment. In other words, one system replaces another after a period when people either moved elsewhere or the system itself collapsed in some way. Notions of discontinuity were more fashionable in the past, when there was far less data to play with. Archaeology was constructed with a textbook or a historical account in one hand – to provide some form of context – and site notebooks and photographs in the other. You concentrated on the details of the site you had just excavated, and only towards the end of the operation did you attempt to place it all in context. Nowadays all of that has changed, because context is being provided by new archaeological finds, as well as by documents.

I have touched on metal detecting, but a far more significant factor in shaping the way we view the past has been the explosion of new information from commercial archaeology, which I discussed in the Introduction. Thanks to computers and Geographical Information Systems (GIS) this store of new information is now available to archaeologists and others. To be more specific, this means that we now have the information to re-examine the way that wics and emporia have traditionally been interpreted.

Two questions spring immediately to mind. The first is perhaps the most obvious: were they isolated, one-off royal foundations that existed to promote and exploit a royal monopoly of imported prestige goods? The answer to that is relatively simple: yes they were, and no they were not. They were, inasmuch as they show all the signs of royal involvement, but they were not isolated, nor did they monopolise all trade – or even most of the trade that was taking place in and around them. There was simply too much going on to attribute everything to some form of royal prerogative. One glance at the map of southern England see (page 47) showing the three wics at Ipswich, London and Southampton reveals that the hinterland of these three places was liberally peppered with subsidiary, but still very significant, settlements and ‘productive’ sites which are positioned close to either Roman roads, ancient routes or navigable rivers. It is most noticeable that none is positioned on the more remote hills of the southern Midlands, in East Anglia or the South Downs. Good access and easy communication were clearly essential. These must be seen as trading places, but that of course does not mean they could not have been settlements or small towns in their own right. It does suggest, however, that royal power was not employed to confine all trade and exchange to the major wics and emporia. The evidence suggests that Middle Saxon trade was indeed organised around the wics and emporia, but that these formed just one part of an integrated system in which many people played an active part.

The second question that we can re-examine with the benefit of so much new information concerns the demise of the wics and emporia. Can we still confidently assert that the best part of a century of abandonment separated the appearance of the first burhs from the last feeble gasps of the declining wics? This suggestion becomes increasingly hard to support if the wics were indeed part of an integrated system, because if they declined and vanished, then surely the system as a whole must also have collapsed. But there is no evidence to suggest that anything of the sort happened. Yes, the wics and emporia declined in the late eighth and early ninth centuries, but certainly Lundenwic never disappears off the map. Nor do ‘productive’ sites simply vanish. Trade within Britain has slowed down by, say, 850, and the Late Saxon successors to the widely traded pottery known as Ipswich Ware (Thetford Ware, Stamford Ware, etc.) were never as widely distributed as their Middle Saxon precursor. This winding down can be attributed in part to political turmoil within the Carolingian Empire across the Channel, and to increasing Viking raids and conflict within Britain. But trade within Britain certainly didn’t cease. There was no hiatus; the Late Saxon economy never hit the buffers.

The emphasis on coins and metalwork from both the wics and the smaller ‘productive’ sites has tended to obscure the true nature of much of the trading that was taking place. I’ve already mentioned that Richard Hodges considers that something of an ‘industrial revolution’ was happening in the eighth century, and the best evidence for this comes in the form of Ipswich Ware.

I remember when I first came across this starkly functional, unglazed, dark grey pottery. I was with my friend and colleague Keith Wade, who had been the deputy director of the Saxon and medieval dig, which I had co-supervised in 1970, at North Elmham Park in central north Norfolk. In the late summer, when digging ended, I went with Keith in search of Ipswich Ware, which he rightly felt was very important because it represented the beginnings of a major Saxon industry. I don’t think either of us realised back then just how important Ipswich Ware was to become. I recall looking at my first sherds and noticing that they were lightly dimpled on the outside, and Keith explaining that this was an example of the slow-wheel technique of manufacture, where the vessel being formed was on an unpowered turntable that was revolved by a sideways flick of the thumb on the vessel itself, which left the distinctive ‘girth grooves’. Thanks to the Ipswich Ware Project we now realise that this pottery was produced in very large quantities and was distributed widely across southern England, presumably along the same roads and rivers that linked the various wics and ‘productive’ sites. If we are not looking at actual batch-based mass production, then we must be getting very close to it. Whatever the true situation, we have now moved well beyond a simple craft-based rural manufacturing tradition to something more standardised and, indeed, industrial.

I have to admit that I was only slightly aware of its importance at the time, but when I was working at North Elmham one of us found a sherd – actually it was a handle – of fine dark pottery which somehow seemed to have acquired a diamond-shaped piece of tinfoil which had stuck to its outside – as if it had accidentally stuck there when the Christmas turkey was being cooked.29 The digger who found it had the good sense not to scrape the foil off with his finger – as I fear I might have done in my naïveté – and he showed it to Keith, who stared at it with eyes like saucers. ‘Good grief,’ he said (actually he used a stronger term), ‘it’s Tating Ware!’ And off he hurried to the director, Peter Wade-Martins, in the site hut. Peter was absolutely delighted, because Tating (pronounced ‘Tarting’) Ware mostly came from the Rhineland, and was the finest and most skilfully produced pottery in late-eighth- or ninth-century Europe.30 It was very high-status stuff indeed, and the best evidence possible for trade.

As I have already mentioned, Keith and I went in search of pottery and pottery kilns when we had finished at North Elmham. In the autumn I visited him on a dig behind a farmyard at the beautiful Essex village of Wicken Bonhunt. The first find he showed me when I got there was another sherd of Tating Ware.

In the early 1970s the gradually increasing quantities of exotic early imported pottery were causing something of a stir. What did it all mean? Today, because we have the coins and metalwork provided by the detectorists, we can see that it was part of a larger pattern of trade. At the time we put the presence of this exotic material down to the Church. There was good evidence that the ruined church at North Elmham, known locally as the Old Minster, which stood just outside the excavations, might in its early stages have been the minster church* of the Saxon see (or seat of the bishop) of the diocese of Elmham, which incorporated most of the northern part of the kingdom of East Anglia (i.e. most of Norfolk). When the dig had finished and all the finds were assessed, it became clear that North Elmham had produced about 30 per cent of all the imported sherds of pottery known from Norfolk. I had chosen the right dig to take part in.

It would now appear that we may not have been wrong in assuming a link with the Church. Other important places and ‘productive’ sites, such as Barking Abbey (Essex), Burgh Castle and Caister-on-Sea (Norfolk), have produced exotic imports and are known to have had links to the Church. So, rather like the links to the ruling elites, it would appear that the Church also wanted its slice of the action, and probably took an active part in encouraging trade: God and Mammon shared the same interests.