Полная версия

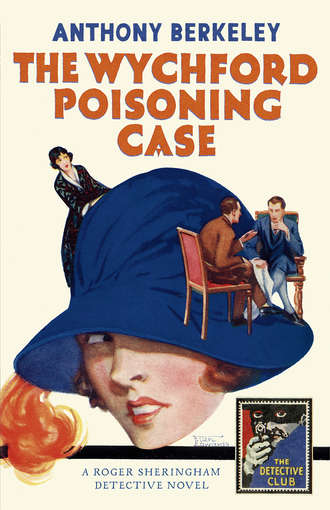

The Wychford Poisoning Case

‘Yes?’ Alec asked with interest. ‘Or else what?’

Roger looked up suddenly. ‘Why, or else that she didn’t murder her husband at all!’ he said equably.

‘But my dear chap!’ Alec was compelled to protest. ‘How on earth do you make that out?’

Roger folded his arms and fixed an unseeing gaze on the meadow on the other side of the little stream.

‘There’s too much evidence!’ he began in an argumentative voice. ‘A jolly sight too much. It’s all too cut and dried. Now somebody manufactured that evidence, didn’t they? Do you mean to tell me that Mrs Bentley deliberately manufactured it herself?’

‘Well,’ said Alec doubtfully. ‘that’s all very well, but who else could have done.’

‘The real criminal.’

‘But Mrs Bentley being the real criminal—!’

‘Now, look here, Alec, do try and clear your mind of prejudice for the moment. Let’s take it that we’re not sure whether Mrs Bentley is guilty or innocent. No, let’s go a step further and assume for the moment her complete innocence, and argue on that basis. What do we get? That somebody else poisoned Bentley; that this somebody else wished Mrs Bentley not only to be accused of the crime but also, apparently, to suffer for it; and that this somebody therefore laid a careful train of the most convincing and damning evidence to lead to the speedy and complete undoing of Mrs Bentley. Now that gives us something to think about, doesn’t it? And take into consideration at the same time the fact that not only was Mrs Bentley to be disposed of in this way, but Bentley himself as well. In other words, this mysterious unknown had a motive for getting rid of Mr just as much as Mrs Bentley; whether one more than the other we can’t yet say, but certainly both. And the plot was an ingenious one; the very fact of getting rid of the second clears the perpetrator of all suspicion of getting rid of the first, you see. Oh, yes, there’s a lot to think about here.’

‘You’re going too fast,’ Alec complained. ‘What about the evidence?’

‘Yes, the evidence. Well, assuming still that Mrs Bentley is innocent, she’ll have an explanation of some sort for the evidence. But unless I’m very much mistaken, it’s going to be a not particularly convincing one and quite incapable of proof—the mysterious unknown, we know, has quite enough cunning to have made sure of that. In fact we now arrive at a positively delightful anomaly—if Mrs Bentley’s explanations by any chance do carry conviction, I should say she is probably guilty; if they’re feeble and childish, I shall be morally sure of her innocence!’

‘Good Lord, what an extraordinary chap you are!’ Alec groaned. ‘How in the world do you get that?’

‘I should have thought it was quite clear. If they’re feeble and childish, it’ll probably be because they’re true (you’ve no idea how frightfully unconvincing the truth can very often be, my dear Alexander); whereas, if they’re glib and pat, it’ll certainly point to their having been prepared beforehand. Once more I repeat—poisoning is a deliberate and cold-blooded business. The criminal doesn’t leave his explanations to the spur of the moment when the police tap him on the shoulder and ask him what about it; he has it all very carefully worked out in advance, with chapter and verse to support it too. That’s why poisoning trials are always twice as long as those for murder by violence; because there’s so much more difficulty in bringing his guilt home to the criminal. And that, in turn, is not because poison in itself is a more subtle means of murder, but because the kind of person who has recourse to it is, in seven cases out of ten, a careful, painstaking and clever individual. Of course you do get plenty of mentally unbalanced people using it too, like Pritchard or Lamson, but they’re rather the exceptions than the rule. The cold, hard, calculating type, Seddon, Armstrong, that kind of man, is the real natural poisoner. Crippen, by the way, was a poisoner by force of circumstances; but then he’s an exception to every rule that you could possibly formulate. I’m always very sorry for Crippen. If ever a woman deserved murdering, Cora Crippen did, and it’s my opinion that Crippen killed her because he was a coward; she had established a complete tyranny over him, and he simply hadn’t got the moral courage to run away from her. That, and the fact that she had got control of all his savings, of course, as Mr Filson Young has very interestingly pointed out. An extraordinarily absorbing case from the psychological standpoint, Alexander. One day I must go into it with you at the length it deserves.’

‘Lord!’ was Alec’s comment on this first lesson in criminology. ‘How you do gas!’

‘That’s as may be,’ said Roger, and betook himself to his pipe again.

‘Well, what about it all?’ Alec asked a minute or two later. ‘What do you want to do about it?’

Roger paused for a moment. ‘It’s a nice little puzzle, isn’t it?’ he said, more as if speaking his thoughts aloud than answering the other question. ‘It’d be nice to unearth the truth and prove everybody else in the whole blessed country wrong—always providing that there is any more truth to unearth. In any case, it’s a pretty little whetstone to sharpen one’s wits on. Yes.’

‘What do you want to do?’ Alec repeated patiently.

‘Take it up, Alexander!’ Roger replied this time, with an air of briskness. ‘Take it up and pull it about and scrabble into it and generally turn it upside down and shake it till something drops out; that’s what I’ve a jolly good mind to do.’

‘But there’ll be people doing that for her in any case,’ Alec objected. ‘Solicitors and so on. They’ll be looking after her defence, if that’s what you mean.’

‘Yes, that is so, of course. But supposing her solicitors and so on are just as convinced of her guilt as everybody else is. It’s going to be a pretty half-hearted sort of defence in that case, isn’t it? And supposing none of them has the gumption to realise that it’s no good basing their defence just on explanations of the existing evidence—that their client is going to be hanged on that as sure as God made little apples—that if they want to save her they’ve got to dig and ferret out new evidence! Supposing all that, friend Alec.’

‘Well? Supposing it?’

‘Then in that case it seems to me that somebody like us is pretty badly needed. Dash it all, they have detectives to ferret out things for the prosecution, don’t they? Well, why not for the defence? Of course, her solicitors may be clever men; they may be going to do all this and employ detectives off their own bat. But I doubt it, Alexander; I can’t help doubting it very much indeed. Anyhow, that’s what I’m going to be—honorary detective for the defence. I appoint myself on probation, pending confirmation in writing. Now then, Alec—what about coming in with me?’

‘I’m game enough,’ Alec replied without hesitation. ‘When do we start?’

‘Well, let’s see; the assizes come on in about six weeks’ time, I think the paper said. We shall want to get finished at least a fortnight before that. That gives us a month. I don’t think we ought to waste any time. What about pushing off tomorrow morning?’

‘Right-ho! But what I want to know is, what exactly are we going to do?’

‘My dear chap, I haven’t the least idea! Whatever happens to occur to us. We shall have to make a bee-line for Wychford, of course, and the first thing we shall want to know is what the defence is to be. That’s going to take a bit of finding out too, by the way; but I don’t see that we can take up any definite line until we’ve heard Mrs Bentley’s story. I’ll try and hammer out a plan of some kind in the meantime. And Alec!’

‘Yes?’

‘For heaven’s sake do try and give me a little more encouragement over this affair than you did at Layton Court!’

CHAPTER IV

ARRIVAL AT WYCHFORD

‘I’VE had one brain-wave at any rate, Alec,’ Roger remarked, settling himself comfortably in the corner of the first-class smoker and hoisting his feet on to the seat opposite.

Alec had just brought the upper part of his body into the carriage after bidding goodbye to a frankly derisive Barbara, and was now lifting their suitcases on to the rack as the train gathered speed—that same half-past ten train, by the way, to which Roger’s attention had been called on the previous morning.

‘Oh?’ he said. ‘What’s that?’

‘Why, the editor of the Daily Courier is by way of being rather a pal of mine. I’m going to call round there on our way through London to ask him if he’ll take me on as unofficial special correspondent.’

‘Are you?’ Alec asked, dropping into his seat. ‘What’s the idea of that?’

‘Well, it occurred to me that we shall be in rather a more favourable position for ramming our way into the heart of things if we’ve got the weight of the Courier behind us than if we just show up as two independent and vulgarly curious gentlemen on their own. The Courier’s name ought to help loosen a hesitating tongue quite a lot. Oh, and by the way, here’s something for you, a list of the important dates in the case that I typed out last night. I’ve got a copy for myself; you can keep that.’

Alec took the paper which Roger was holding out to him and examined it. It was inscribed as follows:

DATES IN THE CASE

June 27 Saturday Mrs Bentley stays with Allen. June 29 Monday Mrs Bentley goes home again. Quarrel. July 1 Wednesday Mrs Bentley buys fly-papers. July 5 Sunday Picnic. Bentley first taken ill. July 6 Monday Bentley better, but stays in bed. July 7 Tuesday Bentley back to business. Mrs Bentley to Four Arts Ball, and stays with Allen. July 8 Wednesday Mrs Bentley goes home. Quarrel, and Mrs Bentley is knocked down. July 9 Thursday Bentley takes flask down to office, subsequently found to contain arsenic. Makes new will in Alfred’s favour. July 10 Friday Bentley taken ill for a second time. July 11 Saturday Bentley much the same. July 12 Sunday Bentley slightly better. July 13 Monday Bentley better still. July 14 Tuesday Bentley has a slight relapse. Second doctor called in. July 15 Wednesday Bentley’s condition unchanged. Mrs Bentley’s letter to Allen intercepted. Nurse arrives. Episode of the Bovril. Bentley taken much worse in evening. July 16 Thursday Bentley dies. Search of Mrs Bentley’s effects and large quantity of arsenic discovered. Doctors refuse death certificate. July 17 Friday Mrs Bentley arrested.‘Thanks,’ said Alec, tucking the paper away in his pocket. ‘Yes, that’ll be useful. Now then, what are you going to do about finding out the lines of Mrs Bentley’s defence, as you said?’

‘Well, I shall take the bull by the horns; go straight to her solicitor, tell him who I am and simply ask him.’

‘Humph!’ said Alec doubtfully. ‘Not likely to get much change there, are you? Not a solicitor who knows his job.’

‘No, none at all. I don’t expect him to tell me for a minute. But I do expect to be able to catch a glimpse of a word or two between the lines. Anyhow, my name ought to be enough to stop them kicking me point-blank out of the door; they will do it politely at any rate. If they ever have heard of me, that is—which I hope and pray!’

‘Yes, there are advantages in being a best-seller, no doubt. How many editions has the latest run through now?’

‘Pamela Alive? Seven, in five weeks. Thanking you kindly. Bought your copy yet?’

The conversation became personal. Very personal.

Arrived at Waterloo a couple of hours later, Roger gave brisk directions. ‘You take the cases along to Charing Cross and put them in the cloakroom, look up a train for Wychford sometime about three o’clock, and then come along and pick me up at the Courier office in Fleet Street. I’m going to get through on the ’phone right away and stop Burgoyne going out to lunch till I’ve seen him, and I’ll wait for you there. Then we can have a spot of lunch at Simpson’s or the Cock, and go on to Charing Cross afterwards. So long!’

They separated on the platform and Roger hurried off to telephone. Burgoyne was in and he made an appointment with him for ten minutes’ time. Jumping into a taxi, he was carried swiftly over Waterloo Bridge and down Fleet Street, arriving in the Great Man’s office with exactly fifteen seconds to spare. Roger rather liked that sort of thing.

It was not Roger’s intention to give any hint, either to Burgoyne himself or to anyone else, of his theory that Mrs Bentley might possibly be the victim of somebody else’s plot rather than the contriver of one of her own making. For one thing it was more of a suspicion than a theory, and his arguments to Alec, interesting though he had made them sound, had been delivered more with the idea of clarifying his own mind on the matter than of stating an actual case. For another thing he preferred, should anything eventually come of this surprising notion, to keep himself the only one in the field. His words to Burgoyne were therefore chosen with some care.

‘This Wychford case,’ he said, when they had shaken hands. ‘Interesting, isn’t it?’

‘It’s been a God-send to us, I can tell you,’ Burgoyne smiled. ‘Carried us all through August, thank heaven. Interesting, is it? Well, I suppose it is in a way. Going to write a book about it, eh?’

‘Well, I might,’ Roger said seriously. ‘At any rate, I want to have a look at it at close quarters. That’s what I’ve come to see you about. You know I’m a keen criminologist, and on top of that the case is simply packed with human interest. Those Allens! There are half a dozen characters down there I’d like to study. Well, what I want to ask you is this. Can I use the Courier’s name as an inducement for them to open their mouths to me? Can you appoint me honorary special correspondent, or something like that? You know I won’t abuse it, and I’d really be awfully grateful.’

But Burgoyne was not editor of the Courier for nothing. He was a wise man.

‘You’ve got something up your sleeve, Sheringham,’ he grinned. ‘I can see that with half an eye. No—don’t trouble to perjure yourself! I see you don’t want to talk about it, so I’m not asking. Yes, you can use the Courier’s name all right. On one condition.’

‘Yes?’ Roger asked, not without apprehension.

‘That if you find out anything (and that’s what I take it you’re really going down for: good lord, man, haven’t I heard you expounding theories on detective-work and the rest of it by the half-mile at a time?)—if you do find out anything, you give us the first option on printing it. At your usual rates, needless to say.’

‘Great Scott, yes—rather! Only too pleased. But don’t expect anything, Burgoyne. I don’t mind admitting that I am going to nose around a bit when I get there, but I’m really only going down out of sheer interest in the case. The psychology—’

‘Write it to me, old man,’ advised Burgoyne. ‘Sorry, but I’m up to the eyes as usual, and you’ve had your two minutes. Don’t mind, do you? That’s all right, then. You chuck our name about as much as you like, and in return you give us first chance on any stuff you write about the case and so on. Good enough. So long, old man; so long.’ And Roger found himself being warmly hand-shaken into the passage outside. There were few people who could deal with Roger, but the editor of the Courier was certainly one of them.

Alec was waiting in the vestibule downstairs, and together they left the building, Roger recounting the success of his mission with considerable jubilation.

‘Yes, that’s going to help us a lot,’ he said, as they marched down Fleet Street. ‘There’s nothing like the hope of seeing your name in a paper like the Courier to make a certain type of person talk. And I have a pretty shrewd idea that both brother William and Mrs Saunderson are just that type, to say nothing of the unpleasant domestic, Mary Blower.’

‘But won’t the Courier have had their own man down there all this time?’

‘Oh, yes; but that doesn’t matter in the least. He won’t have asked the questions that I want to ask. Besides,’ Roger added modestly, ‘there’s another factor in our favour for worming our way into people’s good graces. I hate to keep on reminding you of it, Alexander, but you really are rather inclined to overlook it, you know.’

‘Oh? What’s that?’

‘The fact that I’m Roger Sheringham,’ said that unblushing novelist simply.

Alec’s reply verged regrettably upon crudity. One gathered that Alec was lamentably lacking in a proper respect for his distinguished companion.

‘That’s the worst of making oneself so cheap,’ sighed Roger, as they turned into their destination. ‘If a man is never a hero to his valet, what is he to his fat-headed friends?’

After a thick slab of red steak and a pint of old beer apiece they hailed a taxi and were driven to Charing Cross.

‘Do you know Wychford at all?’ Alec asked when they were seated in the train once again, with a carriage to themselves.

‘Just vaguely. I’ve motored through it, you know.’

‘Um!’

‘Why, do you?’

‘Yes, pretty well. I stayed there for a week once when I was a kid.’

‘Good Lord, why didn’t you tell me that before? You don’t know anybody there, do you?’

‘Yes, I’ve got a cousin living there.’

‘Really, Alec!’ Roger exclaimed with not unjustifiable exasperation. ‘You are the most reticent devil I’ve ever struck. I have to dig things out of you with a pin. Don’t you see how important this is?’

‘No,’ said Alec frankly.

‘Why, your cousin may be able to give us all sorts of useful introductions, besides being able to tell us the local gossip and all sorts of things like that. For goodness’ sake open your mouth and tell me all about it. What sort of a place is Wychford? Does your cousin live in the town itself, or outside it? What can you remember about Wychford?’

Alec considered. ‘Well, it’s a pretty big place, you know. I suppose it’s much the same as any other pretty big place. Lots of sets and cliques and all that sort of thing. My cousin lives pretty well in the middle, in the High Street. She married a doctor there. Nice old house they’ve got, red brick and gables and all that. Just before you get to the pond on the right, coming from London. You remember that pond, at the top of the High Street?’

‘Yes, I think so. Married a doctor, did she? That’s great. We’ll be able to have a look at the medical evidence from the inside, you see, if we want to. What’s the doctor’s name, by the way?’

‘Purefoy. Dr Purefoy. She’s Mrs Purefoy,’ he added helpfully.

‘Yes, I gathered something like that. Not one of the doctors in the case. All right; go on.’

‘Well, that’s about all, isn’t it?’

‘It’s all I shall be able to get out of you, Alec,’ Roger grumbled. ‘That’s quite evident. What taciturn devils you semi-Scotch people are! You’re worse than the real thing.’

‘You ought to be thankful,’ Alec grinned. ‘There’s not much room for the chatty sort when you’re anywhere around, is there?’

‘I disdain to reply to your crude witticisms, Alexander,’ replied Roger with dignity, and went on to reply to them at considerable length.

His harangue was still in full swing when the train stopped at Wychford, and the poorly disguised relief with which Alec hailed their arrival at that station very nearly set him off again. Suppressing with an effort the expression of his feelings, he joined Alec in following the porter with their belongings. They mounted an elderly taxi of almost terrifying instability, and were driven, for a perfectly exorbitant consideration, to the Man of Kent, a hotel which the driver of the elderly taxi was able to recommend with confidence as the best in the town; certainly it was the farthest from the station.

The business of engaging rooms and unpacking their belongings occupied some little time, and Roger ordered tea in the lounge before setting out. Over the meal he expounded the opening of his plan of campaign.

‘There’s nothing like going straight to the fountain-head,’ he said. ‘Nobody in Wychford can tell us so much of what we want to know as Mrs Bentley’s solicitors, so to Mrs Bentley’s solicitors I’m going first of all.’

‘How are you going to find out who they are? Bound to be several solicitors in a place this size.’

‘That simple point,’ Roger said not without pride, ‘I have already attended to. Three minutes’ conversation with the chambermaid gave me the information I wanted.’

‘I see. What do you want me to do? Come with you, or stay here?’

‘Neither. I want you to go and call on your admirable cousin and see if you can wangle an invitation to some meal in the very near future for both of us. Not tea, because I want the husband to be present as well and doctors’ hours for tea are a little uncertain. Don’t say why we’ve come; just tell her that we expect to be here for a few days. You can say that I’ve come to inspect the local Roman remains, if you like.’

‘Are there any Roman remains here?’

‘Not that I know of. But it’s a pretty safe remark. Every town of any size must have Roman remains: its a sort of guarantee of respectability. And use the cunning of the serpent and the guilelessness of a dove. Can I rely on you for that?’

‘I’ll do my best.’

‘Spoken like a Briton!’ approved Roger warmly. ‘And after all, who can do more than that? Answer, almost anybody. But don’t ask me to explain that because—’

‘I won’t!’ said Alec hastily.

Roger looked at his friend with reproach. ‘I think,’ he said in a voice of gentle suffering, ‘that I’ll be getting along now.’

‘So long, then!’ said Alec very heartily.

Roger went.

He was back again in less than half an hour, but it was after six before Alec returned. Roger, smoking his pipe in the lounge with growing impatience, jumped up eagerly as the other’s burly form appeared in the doorway (Alec had got a rugger blue at Oxford for leading the scrum, and he looked it) and waved him over to the corner-table he had secured. The lounge was fairly full by this time, and Roger had been at some pains to keep a table as far away from any other as possible.

‘Well?’ he asked in a low voice as Alec joined him. ‘Any luck?’

‘Yes. Molly wants us to go to dinner there tonight. Just pot-luck, you know.’

‘Good! Well done, Alec.’

‘She seemed quite impressed to hear I was down with you,’ Alec went on with pretended astonishment. ‘In fact, she seems quite keen about meeting you. Extraordinary! I can’t imagine why, can you?’

But Roger was too excited for the moment even to wax facetious. He leaned across the little table with sparkling eyes, making no attempt to conceal his elation.

‘I’ve seen her solicitor!’ he said.

‘Have you? Good. Surely you didn’t get anything out of him, did you?’

‘Didn’t I just! Roger exclaimed softly. ‘I got everything.’

‘Everything?’ repeated Alec startled. ‘Great Scott, how did you manage that?’

‘Oh, no details. Nothing like that. I was only with him for a couple of minutes. He was a dry, precise little man, typical stage solicitor; and he wasn’t giving away if he knew it. Oh, nothing at all. But he didn’t know it, you see, Alexander. He didn’t know it!’