Полная версия

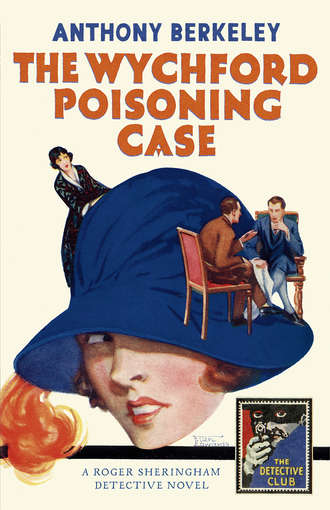

The Wychford Poisoning Case

‘Diagnosis granted,’ Alex agreed: ‘I noticed that. Hysterical kind of ass, I thought. Go on.’

‘Well, when our couple returned from France, they bought a large and comfortable house in the town of Wychford, which lies about fifteen miles south-east of London and possesses an excellent train-service for the tired businessman. Thence, of course, friend John would travel up to town every day except Saturdays, a day on which nobody above the rank of assistant-manager dare show his face in the streets of London or everybody would think his firm is going bankrupt: remember that if you ever go into business, Alec.’

‘Thanks, I will.’

‘Well, eighteen months after the Bentley’s arrival in England, the father, instead of retiring from work in the ordinary way, makes a better job of it and dies, leaving the business to the two sons who are in it, in the proportion of two-thirds to John and one-third to William, the second son. To the third son, Alfred, he left most of the residue of his estate, which amounted in value to much the same as William’s share of the business. John, then, who seems to have been the old man’s favourite, came off very decidedly the best of the three. John therefore picked up the reins of the business and for the next three years all went well. Not quite so well as it had done, because John wasn’t the man his father had been; still, well enough. So much, I think, for the family history. Got all that?’

Alec nodded. ‘Yes, I knew most of that before, I think.’

‘So now we come from the general to the particular. In other words, to the Bentley ménage. Now, have you formed any estimate of the characters of these two, Monsieur and Madame? Could you give me a short character-sketch of Bentley himself, for instance?’

‘No, I’m blessed if I could. I was concentrating on the facts, not the characters.’

Roger shook his head reprovingly. ‘A great mistake, Alexander; a great mistake. What do you think it is that makes any great murder case so absorbingly interesting? Not the sordid facts in themselves. No, it’s the psychology of the people concerned; the character of the criminal, the character of the victim, their reactions to violence, what they felt and thought and suffered over it all. The circumstances of the case, the methods of the murderer, the reasons for the murder, the steps he takes to elude detection—all these arise directly out of character; in themselves they’re only secondary. Facts, you might say, depend on psychology. What was it that made the Thompson-Bywaters case so extraordinarily interesting? Not the mere facts. It was the characters of the three protagonists. Take away the psychology of that case and you get just a sordid triangle of the most trite and uninteresting description. Add it, and you get what the film-producers call a drama packed with human interest. Just the same with the Seddon case, Crippen, or, to become criminologically classical, William Palmer. A grave error, my Alexander; a very grave error indeed.’

‘Sorry; I seem to have said the wrong thing. All right. What about the psychology of the Bentleys, then?’

‘Well, John Bentley seems to emerge to me as a fussy, rather irritating little man, very pleased with himself and continually worrying about his health; probably a bit of a hypochondriac. Reading between the lines, I don’t think brother William got on at all well with him—no doubt because he was much the same sort of fellow himself. It doesn’t need any reading between the lines to see that his wife didn’t. She appears as a happy, gay little creature, not overburdened with brains but certainly not deficient in them, always wanting to go out somewhere and enjoy herself, theatres, dance-clubs, car-rides, parties, any old thing. Well, just imagine the two of them together—and remember that she’s sixteen years younger than her husband. She wants to go to a dance, he won’t take her because it would interfere with his regular eight-hours’ sleep; she wants to go to a race-meeting, he thinks standing about in the open air would give him a cold; she wants to go to the theatre, he thinks the man in the next seat might be carrying influenza germs. Of course the inevitable happens. She gets somebody else to take her.’

‘Ah!’ observed Alec wisely. ‘Allen!’

‘Exactly! Allen. Well, that’s where the facts of the case proper seem to begin; with that weekend Mrs Bentley spent with Allen at the Bischroma Hotel.’

‘Now we’re getting to it.’

Roger paused to re-light his pipe, which had gone out under the flood of this eloquence.

‘Now,’ he agreed, ‘we’re getting to it. That was on the 27th of June; Mrs Bentley going home to Wychford again on the 29th and telling her husband that she’d been staying with a girl friend of hers from Paris. Bentley doesn’t seem to have suspected anything: which is what one might expect with that complacent, self-centred little type. But he has got his doubts about Allen. Allen’s name crops up in the conversation that same night, we learn from brother William, who was staying in the house for the whole summer, and Bentley forbids his wife to have anything more to do with the chap. Madame laughs at him and asks if he’s jealous.’

‘The nerve of her!’

‘Oh, quite natural, in the circumstances. He says he’s not jealous in the least, thank you, but he’s just given her his instructions and will she be kind enough to see that they are carried out (can’t you just see him at it!) Madame, ceasing to laugh, tells him not to be an ass. Bentley retorts suitably. Anyhow, the upshot is that they have a blazing row, all in front of brother William, and Madame flies upstairs, chattering with fury, to pack her bag for France that very minute.’

‘Pity she didn’t!’

‘I agree. Brother William steps in, however, and persuades her to stay that night at any rate, and in the morning he gets in a Mrs Saunderson from down the same road, with whom Mrs Bentley has been getting very pally during the last couple of years, and she manages to pacify the lady to such an extent that there is a grand reconciliation scene that same evening, with John and Jacqueline in the centre surrounded by the triumphant beams of Brother William and Mrs Saunderson. That was on June the 29th. On July the 1st Mrs Bentley buys two dozen arsenical fly-papers from a chemist in Wychford.’

‘Well, you must admit that’s suspicious, at any rate.’

‘Oh, I do. Suspicious isn’t the word. The parlourmaid, Mary Blower, and the housemaid, Nellie Green, both see these fly-papers soaking in three saucers during the next two days in Mrs Bentley’s bedroom. There had never been fly-papers of that kind in the house before, and they were not a little intrigued about them; Mary Blower especially, as we shall see later. That same day Bentley, fussing as usual over his health, goes to see his doctor in Wychford, Dr James, and gets himself thoroughly over-hauled. Dr James tells him that he’s a little run down (the stock comment for people of that kind), but that there’s nothing constitutionally wrong with him; he gives the man a bottle of medicine to keep him quiet, a mild tonic, mostly iron. Four days later, on a Sunday, Bentley complains at breakfast that he’s not feeling up to the mark. William tells us with a properly shocked air that Mrs Bentley received this information callously and told him straight out that there was nothing the matter with him; but really, the poor lady must have heard the same thing at so many breakfasts before that one can understand her not being exactly prostrated by it. In any case, he’s not feeling so bad that he can’t go out for a picnic that same afternoon with her and William, and Mr and Mrs Allen.’

‘Having climbed down over the Allen business, apparently,’ Alec commented.

‘Yes. But of course he had to. With the possible exception of Mrs Saunderson, the Allens were their closest friends in Wychford. Unless he wanted to precipitate an open scandal, he couldn’t maintain his stand about Allen. To do so would be tantamount to informing Mrs Allen that, in Bentley’s opinion, her husband was in danger of becoming unfaithful to her. One’s sympathies are certainly with Bentley there; the position was a very nasty one for him. And I can’t imagine him liking the man much. They must have been complete opposites, mustn’t they? Bentley, fussy, peevish, and on the small side; Allen, big, breezy, hearty, strong, and packed with self-confidence—or so I read him. Yes, I can quite understand Bentley’s uneasiness about friend Allen just about that time.’

‘And Mrs Allen didn’t know her husband was taking Mrs Bentley out all this time?’

‘So I should imagine. She probably guessed he was taking somebody out, but not that it was Mrs Bentley. I can’t quite get Mrs Allen. She seemed perfectly calm, even icy, in the police-court; and probably her deliberate manner did Mrs Bentley actually more harm than Mrs Saunderson’s hysteria. She is the wronged wife, you see, and she’s certainly investing an ignominious rôle with a good deal of quiet dignity. Mrs Saunderson’s the person who appears to me to emerge worse than anybody else in the whole case; she seems really rancorous against her late best friend. What inhuman brutes some of these women can be to each other, when one of them’s properly up against it! However. Well, Bentley comes back from the picnic complaining that he feels a good deal worse and goes straight to bed, where shortly afterwards he is very sick. He attributes his trouble to sitting about on damp grass at the picnic; the police say that it followed the first administration to him by his wife of the solution of arsenic obtained from the fly-papers.’

‘Um!’ said Alec thoughtfully.

‘He passed a fairly good night, but stayed in bed during the next day though feeling decidedly better. Dr James called in during the morning and, after a thorough examination, came to the conclusion that the man was a chronic dyspeptic. He changed his medicine and gave instructions about his diet, and the next day, Tuesday, Bentley was well enough to go back to business. That same night Mrs Bentley went with Allen to the Four Arts Ball at Covent Garden, the last big public event of the season, going back with him afterwards to the Bischroma again. The evidence of the proprietor, Mr Nume, is quite conclusive on that point.’

‘Bit risky, after the last row.’

‘Oh, yes, risky enough. But as I see Madame Bentley at that time (leaving the question of her subsequent guilt or innocence out of it for the moment), she just didn’t care a rap what happened. We don’t know whether she was really in love with Allen or not, but we do know that her middle-aged husband not only bored her, but irritated her as well; and in these circumstances a woman is simply ripe for madness. The effects of the late reconciliation had probably quite worn off, and she simply didn’t mind whether she were found out or not. Quite possibly she hoped she would be, so that Bentley would divorce her and give her her freedom. There were no children to complicate things, you see.’

‘Might be something in that,’ Alec admitted.

‘Well, after that matters begin to move swiftly. There’s a blazing row when she gets back the next day, and this time Bentley loses his head altogether, knocks her down and gives her a black eye. Again Madame flies upstairs to pack for France, again brother William and Mrs Saunderson intervene in the rôle of good angels, and again the quarrel is patched up somehow or other. Madame Bentley stays at home. That is Wednesday. Bentley has been to his office that day, and he goes on Thursday too, this time taking in a thermos flask some food specially prepared for him by Mrs Bentley herself. He left the flask there, as you know; the residue inside was subsequently analysed and it was found to contain arsenic.’

‘How is she going to get over that?’

‘How, indeed? That’s just what I’m wondering. On this day, Thursday, Bentley’s younger brother, Alfred, calls in during the morning and Bentley tells him that, in consequence of his wife’s behaviour, he is altering his will, leaving her only a bare pittance; nearly the whole of his estate, which consisted chiefly of his holding in the business, he is dividing between his two brothers—not much to William, because he and William don’t get on very well, by far the greater share to Alfred himself. On his death, therefore, Alfred will own the larger holding in the business, although he has never been in it and William has been there all his life.’

‘Yes, I saw that. Why on earth did he do that?’

‘Well, it’s obvious enough. Bentley, though a big enough fool in private life, wasn’t so in business at all. William, on the other hand, was, and Bentley knew it. Once let the business get into William’s full control, and in no time it would go pop. Alfred, on the contrary, is a very different sort of fellow—very different from both his brothers. His character strikes me as more like that of a Scotch elder than a member of the Bentley family—dour, stern, uncompromising, hard and not far removed from cruel; also a bit, if I’m not wrong, on the avaricious side. An amazing contrast. Anyhow, there can’t be a better way of throwing light on his character than by reminding you that as soon as he heard this news, prudent brother Alfred took his brother off to a solicitor there and then that very morning and stood over him while the new will was drawn up! Oh, a very canny man, brother Alfred.’

‘I think I prefer him to Bentley himself though, for all that.’

‘That’s the Scotch strain in you coming out, Alec; you recognise a fellow-feeling for brother Alfred, no doubt. Well, and so we come to Bentley’s last illness and death. Do you want to break off here and go on tickling the trout?’

‘No!’ said Alec surprisingly. ‘It’s rather interesting to hear the whole thing like this in one connected whole instead of in snippets; though what you’re getting at I’m hanged if I can see. Carry on!’

‘Alec,’ said Roger with emotion, ‘this is the most remarkable tribute I have ever had in the course of a long and successful career.’

CHAPTER III

MR SHERINGHAM ASKS WHY

‘THE next day,’ Roger continued after a short pause, ‘Friday, the 10th of July, Bentley felt too ill in the morning to go to work. He complained of pains in the leg, and was vomiting. Dr James was called in and prescribed for him. The next day the pains had disappeared, but the vomiting continued, which Dr James attributed to the morphia he had given him on the previous day. On the Sunday he was a little better; on the Monday a little better still. On the next day Dr James expected him to be almost recovered, but instead of this a slight relapse set in and, on Mrs Bentley’s suggestion, another doctor was called in, Dr Peters. Dr Peters also diagnosed acute dyspepsia, and gave the patient a sedative. On the Wednesday he was no better.

‘Now this day, the 15th of July, is a very important one indeed, and we must examine it in some detail. It was in the course of this day that the idea was first mooted that all was not as it should be.

‘All this time Mrs Allen and Mrs Saunderson had been continually in and out of the house, while Mrs Bentley was nursing her husband—doing the household shopping for her, running errands, giving advice and generally fussing round. On this evening Mary Blower (who seems to have a grudge of some sort against her mistress) told Mrs Saunderson of the fly-papers she had seen soaking a fortnight before. Mrs Saunderson, twittering with excitement, tells Mrs Allen, and in three minutes these two excellent ladies have decided that Mrs Bentley is poisoning her husband. And since that time not a single person seems to have had the least doubt of it. Off goes Mrs Saunderson to telephone brother William at the office and tell him to come back to Wychford at once, while Mrs Allen runs round to the post-office to send a mysterious telegram to brother Alfred. Of all this Mrs Bentley, of course, remains in complete ignorance. Late in the morning the brothers arrive, and you can imagine the seething excitement.

‘In the meantime, Mrs Bentley has decided that she can’t go on nursing her husband alone and has telegraphed for a nurse, who arrived just after lunch. Brother Alfred, who already seems to have assumed entire control of the household, takes the nurse aside at once and tells her that nobody but herself is to administer anything to the patient, as they have reason to believe that something mysterious is going on. With the consequence that we now have a twittering nurse as well as twittering friends and twittering brothers. In fact, the only person in the house just at that time who does not seem to have been twittering is Mrs Bentley herself.

‘But there’s more excitement to come. During the afternoon Mrs Bentley handed a letter to Mary Blower and asked her to run out to the post with it. Mary Blower looks at the address and sees that it is to Mr Allen, who was at this time away from Wychford on business in Bristol. Instead of posting it, she hands it over to Mrs Allen, who promptly opens it. And then the fat was in the fire with a vengeance, for Mrs Bentley had not only been idiot enough to make reference to their weekend at the Bischroma, but she had mentioned her husband’s illness in terms that certainly weren’t very sympathetic—though it’s more than possible that she didn’t then realise the serious state he was in.

‘Anyhow, coming after the fly-papers revelation, that was enough for the four. Where there had been any possibility of doubt before, there was none now. Brother Alfred put on his hat at once, went round to the two doctors and told them both the whole story. The three of them held a council of war, and decided that Mrs Bentley must be watched continuously.

‘Well, that was bad enough, but there was still another piece of news waiting for brother Alfred when he got back, and that certainly is the most damning thing of all. The nurse had come down a short time ago with a bottle of Bovril in her hand and explained that she had seen Mrs Bentley pick it up in a surreptitious way and convey it out of the bedroom, hiding it in the folds of her frock; a few minutes later she brought it back and replaced it, when she thought the nurse’s back was turned, in the exact spot from which she had taken it. That bottle was handed over to the doctors next day and was subsequently found to contain arsenic.’

‘Well, that I am dashed if you can get over!’ Alec observed.

‘It isn’t for me to get over it,’ pointed out Roger mildly. ‘I’m not saying the woman is innocent. All I say is that we ought to bear the possibility of her innocence in mind, and not assume her guilt as a matter of course. In any case I am most uncommonly interested to hear what she’s got to say about that particular incident. Well, up to this time, you’ve got to remember, Bentley’s condition, though serious, wasn’t considered to be in any way dangerous (which does go a long way to explain the somewhat flippant tone of Mrs Bentley’s letter to Allen that has helped to create so much prejudice against her); but that same night things took a very rapid turn for the worse. Both doctors were hurriedly summoned, and they were with him all night. By the next morning Mrs Bentley and the others were warned that there could be very little hope for him, at midday he became unconscious and at seven o’clock in the evening he died.

‘But that wasn’t all. Mrs Bentley had been removed at once, by brother Alfred’s orders, to her own bedroom, where she was kept practically a prisoner, and the other four immediately began a systematic search of the whole place. Their efforts were not unrewarded. In Bentley’s dressing-room there stood a trunk belonging to his wife. In the tray of this was a medicine bottle containing, as shown later, a very strong solution of arsenic in lemonade, together with a handkerchief belonging to Mrs Bentley which was also impregnated with arsenic. In a medicine-chest were the remains of the bottles of medicine prescribed by Dr James (two) and Dr Peters (one). None of these prescriptions contained arsenic, but arsenic was subsequently discovered in each bottle in appreciable quantities. And lastly, in a locked drawer in Mrs Bentley’s own bedroom there was found a small packet containing no less than two whole ounces of pure arsenic—actually enough to kill more than a couple of hundred people! And that was that.’

‘I should say it was!’ Alec agreed.

‘Of course the doctors refused a death-certificate. The police were called in, and Mrs Bentley was promptly arrested. Two days later a post-mortem was held. There was no doubt about the cause of death. The stomach and the rest of it were badly inflamed. Death due to inflammation of the stomach and intestines set up by an irritant poison—which in this case was the medical way of saying death from arsenical poisoning. The usual parts of the body were removed and placed in sealed jars for examination by the Government analyst. You read the result this morning in his evidence before the magistrates—at least three grains of arsenic in the body at the time of death, or half a grain more than the ordinary fatal dose, meaning that shortly before death there must have been a good deal more still; arsenic in the stomach, intestines, liver, kidneys, everywhere! And also, significant in another way, arsenic in the skin, nails and hair; and that means that arsenic must have been administered some considerable time ago—a fortnight, for instance, or about the time of that picnic. Is it any wonder that the coroner’s jury brought in a verdict tantamount to wilful murder against Mrs Bentley, or that the magistrates have committed her for trial?’

‘It is not!’ said Alec with decision. ‘They’d have been imbeciles if they hadn’t.’

‘Quite so,’ said Roger. ‘Exactly.’ And he began to smoke very thoughtfully indeed.

There was a little pause.

‘Come on,’ said Alec. ‘You know you’ve got something up your sleeve.’

‘Oh, no. I’ve got nothing up my sleeve.’

‘Well, there’s something in your mind, then. Let’s have it!’

Roger took his pipe out of his mouth and pointed the short stem at his companion as if to drive his next remark home with it. ‘There is a question that I can’t find an answer to,’ he said slowly, ‘and it’s this—why the devil so much arsenic?’

‘So much?’

‘Yes. Why enough to kill a couple of hundred people when there’s only one to be killed? Why? It isn’t natural.’

Alec pondered. ‘Well, surely there might be two or three explanations of that. She wanted to make sure of the job. She didn’t know what the fatal dose was. She—’

‘Oh, yes; there are two or three explanations. But not one of them is the least bit convincing. You don’t think people go in for poisoning without finding out what the fatal dose is, do you? Poisoning is a deliberate, cold-blooded job. Such a simple measure as looking up the fatal dose in any encyclopædia or medical reference book would be the very first step.’

‘Um?’ said Alec, not particularly impressed.

‘And then there’s another thing. Why in the name of all that’s holy buy fly-papers when there’s all that amount of arsenic in the house already?’

‘But perhaps there wasn’t,’ Alec retorted quickly. ‘Perhaps she got the other arsenic after the fly-papers.’

‘Well, suppose she did. The same objection applies just as well. Why buy all that amount of arsenic when she’d already got half a dozen fatal doses out of the fly-papers? And once more, I haven’t seen any police evidence offered to prove that Mrs Bentley did buy that arsenic. It’s proved to have been in her possession, but it hasn’t been shown how it came there. The police seem to be taking it completely for granted that as she had it, it must have been she who bought it.’

‘Is that very important?’

‘I should have said, vitally! No, look at it how you like, the question of this superabundance of arsenic does not simplify the case, as everybody seems to have assumed; in my opinion it infernally complicates it.’

‘It is interesting,’ Alec admitted. ‘I’d never looked on it like that before. What do you make of it, then?’

‘Well, there seem to me only two possible deductions. Either Mrs Bentley is the most imbecile criminal who ever existed and simply went out of her way to manufacture the most damning evidence against herself—which, having formed my own opinion of her character, I am most unwilling to believe. Or else—!’ He paused and rammed down a few straggling ends of tobacco into the bowl of his pipe.