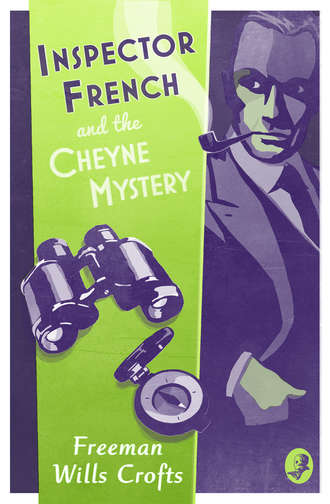

Полная версия

Inspector French and the Cheyne Mystery

The sealed envelope was of a size which would hold a foolscap sheet folded in four, and was fairly bulky. It was inscribed: ‘To Maxwell Cheyne, of Warren Lodge, Dartmouth, Devonshire, from Arnold Price, third officer, S.S. Maurania,’ and on the top was written: ‘Please retain this envelope unopened until I claim it or until you have received authentic news of my death. Arnold Price.’ Cheyne had acknowledged it, promising to carry out the instructions, and had then sent the envelope to his bank, where it had since remained.

The insinuating voice of Lamson broke through his thoughts.

‘I think, Mr Cheyne, when you hear the reasons for our request, you will give it all due consideration. For one—’

What? Break faith with Price? Go back on his friend? Rage again choked Cheyne’s utterance. Stutteringly he cursed the other, once again demanding under blood-curdling threats of future vengeance his immediate liberty. Through his passion he heard the voice of the other saying he was sorry but he really could not help it, the panel slid shut, and darkness and silence, save for the sounds of the sea, reigned in the Enid’s cabin.

4

Concerning A Peerage

When Maxwell Cheyne’s paroxysm of fury diminished and he began once more to think collectedly about the unpleasant situation in which he found himself, a startling idea occurred to him. Here at last, surely, was the explanation of his previous adventures! The drugging in the hotel in Plymouth, the burglary at Warren Lodge, and now his kidnapping on the Enid were all part and parcel of the same scheme. It was for Price’s letter that his pocket-book was investigated while he lay asleep in the private room at the Edgecombe; it was for Price’s letter that his safe was broken open and his house searched by other members of the conspiracy, and it was for Price’s letter that he now lay, a prisoner aboard this infernal launch.

A valuable document, this of Price’s must surely be, if it was worth such pains to acquire! Cheyne wondered how it had never occurred to him that it might represent the motive of the earlier crimes, but he soon realised that he had never thought of it as being of interest to anyone other than Price. Indeed, Price himself referred to his enclosure as ‘some private papers, of interest to myself only.’ In that last phrase Price had evidently been wrong, and Cheyne wondered whether he had been genuinely mistaken, or whether he had from distrust of himself deliberately misstated the case in order to minimise the value of the document. Price had certainly not shown himself anxious to regain it at the earliest possible moment. On the conclusion of peace he had not accepted demobilisation. He had applied for and obtained a transfer to the middle East, where he had commanded one of the transports plying between Basrah and Bombay in connection with the Mesopotamian campaign. So far as Cheyne knew, he was still there. He hadn’t heard of him for many months, not, indeed, since he went out.

While Cheyne had been turning over these matters in his mind the launch had evidently been approaching land, as its rather wild rolling and pitching had gradually ceased and it was now floating on an even keel. Cheyne had been conscious of the fact despite his preoccupation, but now his musings were interrupted by the stopping of the motor and a few seconds later by the plunge of the anchor and the rattle of the running chain. In the comparative silence he shouted himself hoarse, but no one paid him the least attention. He heard, however, the dinghy being drawn up to the side and presently the sound of oars retreating, but whether one or both of his captors had left he could not tell. In an hour or two the boat returned, but though he again shouted and beat the door of his cabin, no notice was taken of his calls.

Then began for Cheyne a period which he could never afterwards look back on without a shudder. Never could he have believed that a night could be so long, that time could drag so slowly. He made himself as comfortable as he could in one of the bunks, but as the clothes and the mattress had been removed, his efforts were not crowned with much success. In spite of his weariness and of the growing exhaustion due to hunger, he could not sleep. He wanted something to drink. He was surprised to find that thirst was not localised in a parched throat or dry mouth. His whole being cried out for water. He could not have realised nor described the sensation, but it was very intense, and with every hour that passed it grew stronger. He turned and tossed in the narrow bunk, his restlessness and discomfort continually increasing. At last he dozed, but only to fall into horrible dreams from which he awaked unrefreshed and thirstier than ever.

Cheyne had plenty of spirit and dash, but he lacked in staying power, and when the inevitable period of reaction to his excitement and rage came he became plunged in a deep depression. These fellows had him in their power. If this went on and they really carried out their threat he would have to give way sooner or later. He hated to think he might betray a trust; he hated still more to be coerced into doing anything against his own will, but when, as it seemed to him, weeks later, the panel shot back and Lamson’s face appeared, his first decision was shaken and he waited sullenly to hear what the other had to say.

The man was polite and deprecating rather than blustering, and seemed anxious to make it as easy as possible for Cheyne to capitulate.

‘I hope, Mr Cheyne,’ he began, ‘you will allow me to explain this matter more fully, as I cannot but think you have at least to some extent misunderstood our proposal. I did not tell you the whole of the facts, but I should like to do so now if you will listen.’

He paused expectantly. Cheyne glowered at him, but did not reply and Lamson resumed:

‘The matter is somewhat complicated, but I will do my best to explain it as briefly as I can. In a word, then, it relates to a claim for a peerage. I must admit to you that Lamson is not my name—it is Price, and the Arnold Price whom you knew during the war is my second cousin. Arnold’s uncle and my father’s cousin, St John Price, is, or rather was, in the diplomatic service, and it is through his discoveries that the present situation has arisen.

‘It happened that this St John Price had occasion to visit South Africa on diplomatic business during the war, and as luck would have it he took his return passage on the Maurania, the ship on which his nephew Arnold was third officer. But he never reached England. He met his death on the journey under circumstances which involved a coincidence too remarkable to have happened otherwise than in real life.’

In spite of himself Cheyne was interested. Price glanced at him and went on:

‘One night at the end of the voyage when they were running without lights up the Channel, a large steamer going in the same direction as themselves suddenly loomed up out of the darkness and struck them heavily on the starboard quarter … My cousin was on deck, though not in charge. He saw the outlines of the vessel as she was closing in, and he also saw that a passenger was standing at the rail just where the contact was about to take place. At the risk of his own life he sprang forward and dragged the man back. Unfortunately he was not in time to save him, for a falling spar broke his back and only just missed killing Arnold. Then, as you may have guessed from what I said, it turned out that the passenger was none other than St John Price. My cousin had tried to save his own uncle.’

Once more Price paused, but Cheyne still remaining silent he continued:

‘St John lingered for some hours, during most of which time he was conscious, and it was then that he told Arnold about his belief that he, Arnold, was heir to the barony of Hull. I don’t know, Mr Cheyne, if you are aware that the present Lord Hull is a man well on to eighty and is in failing health. He has no known heir, and unless some claimant comes forward speedily, the title will in the course of nature become extinct. As you probably know also, Lord Hull is a man of enormous wealth. St John Price believed that he, Arnold and myself were all descended from the eldest son of Francis, the fifth Baron Hull. This man had lived an evil, dissolute life, and England having become too hot to hold him, he had sailed for South Africa in the early part of the last century. On his father’s death search was made for him, but without result, and the second son, Alwyn,-inherited. St John had after many years’ labour traced what he believed was a lineal descent from the scapegrace, and he had utilised his visit to South Africa to make further inquiries. There he had unearthed the record of a marriage, which, he believed, completed the proofs he sought. As he knew he was dying, he handed over the attested copy of the marriage register to Arnold, at the same time making a new will leaving all the other documents in the case to Arnold also.

‘When Arnold received his next leave he went fully into the matter with his solicitor, only to find that one document, the register of a birth, was missing. Without this he could scarcely hope to win his case. The evidence of the other papers tended to show that the birth had taken place in India, probably at Bombay, and Arnold therefore applied for a transfer into a service which brought him to that country, in the hope that he would have an opportunity to pursue his researches at first hand. It was there that I met him—I am junior partner in Swanson, Reid & Price’s of that city—and he told me all that I have told you.

‘Before going to the East he sealed up the papers referring to the matter and sent them to you. If you will pardon my saying so, I think that there he made a mistake. But he explained that he knew too much about lawyers to leave anything in their hands, that they would fight the case for their own fees whether there was any chance of winning it or not, and that he wanted the papers to be in the hands of an honest man in case of his death.

‘I pointed out that I was interested in the matter also, but he said No, that he was the heir and that during his life the affair concerned him alone. Needless to say, we parted on bad terms.

‘Now, Mr Cheyne, you can see why I want those papers. Though Arnold is my cousin I doubt his honesty. I want to see exactly how we both stand. I want nothing but what is fair—as a matter of fact I can get nothing but what is fair—the law wouldn’t allow it. But I don’t want to be done. If I had the papers I would show them to a first-rate lawyer. If Arnold is entitled to succeed he will do so, if I am the heir I shall, if neither of us no harm is done. We can only get what the law allows us. But in any case I give my word of honour that, if I succeed, Arnold shall never want for anything in reason.’

Price was speaking earnestly and his manner carried conviction to Cheyne. Without waiting for a reply he proceeded.

‘You, Mr Cheyne, if you will excuse my saying it, are an outsider in the matter. Whether Arnold or I or neither of us succeeds is nothing to you. You want to do only what is fair to Arnold, and you have my most solemn promise that that is all I propose. If you enable me to test our respective positions by handing over the papers to me you will not be letting Arnold down.’

When Price ceased speaking there was silence between the two men as Cheyne thought over what he had heard. Price’s manner was convincing, and as far as Cheyne could form an opinion, the story might be true. It certainly explained the facts adequately, and Cheyne believed that the statements about Lord Hull were correct. All the same he did not believe this man was out for a square deal. If he could only get what the law allowed, would not the same apply whether he or Arnold conducted the affair? Cheyne, moreover, was still sore from his treatment, and he determined he would not discuss the matter until he had received satisfactory replies to one or two personal questions.

‘Did you drug me in the Edgecombe hotel in Plymouth a week ago and then go through my pockets, and did you the same evening burgle my house, break open my safe and mishandle my servants?’

It was not exactly a tactful question, but Price answered it cheerfully and without hesitation.

‘Not in person, but I admit my agents did these things. For these also I am anxious to apologise.’

‘Your apologies won’t prevent your having a lengthened acquaintance with the inside of a prison,’ Cheyne snarled, his rage flickering up at the recollection of his injuries. ‘How do your confederates come to be interested?’

‘Bought,’ the other admitted sweetly. ‘I had no other way of getting help. I have paid them twenty pounds on account and they will get a thousand guineas each if my claim is upheld.’

‘A self-confessed thief and crook as well as a liar! And you expect me to believe in your good intentions towards Arnold Price!’

An unpleasant look passed across the other’s face, but he spoke calmly.

‘That may be all very well and very true if you like, but it doesn’t advance the situation. The question now is: Are you prepared to hand over the letter? Nothing else seems to me to matter.’

‘Why did you not come to me like an ordinary honest man and tell me your story? What induced you to launch out into all this complicated network of crime?’

Price smiled whimsically.

‘Well, you might surely guess that,’ he answered. ‘Suppose you had refused to give me the letter, how was I to know that you would not have put it beyond my reach? I couldn’t take the risk.’

‘Suppose I refuse to give it to you now?’

‘You won’t, Mr Cheyne. No one in your position could. Circumstances are too strong for you, and you can hand it over and retain your honour absolutely untarnished. I do not wish to urge you to a decision. If you would prefer to take today to think over it, by all means do so. I sent the wire to Mrs Cheyne shortly before six last night, so she will not be uneasy about you.’

Though the words were politely spoken, the threat behind them was unmistakable and fell with sinister intent on the listener’s ears. Rapidly Cheyne considered the situation. This ruffian was right. No one in such a situation could resist indefinitely. It was true he could refuse his consent at the moment, but the question would come up again that evening and the next morning and again and again until at last he would have to give way. He knew it, and he felt that unless there was a strong chance of victory, he could not stand the hours of suffering which a further refusal would entail. No, bitter as the conclusion was, he felt he must for the moment admit defeat, trusting later to getting his own back. He turned back to Price.

‘I haven’t got the letter here. I can only get it for you if you put me ashore.’

That this was a victory for Price was evident, but the young man showed no elation. He carefully avoided anything in the nature of a taunt, and spoke in a quiet, businesslike way.

‘We might be able to arrange that. Where is the letter?’

‘At my bank in Dartmouth.’

‘Then the matter is quite simple. All you have to do is to write to the manager to send the letter to an address I shall give you. Directly you do so you shall have the best food and drink on the launch, and directly the letter is in our hands you will be put ashore close to your home.’

Cheyne still hesitated.

‘I’ll do it provided you can prove to me your statements. How am I to know that you will keep your word? How am I to know that you won’t get the letter and then murder me?’

‘I’m afraid you can’t know that. I would gladly prove it to you, but you must see that it’s just not possible. I give you my solemn word of honour and you’ll have to accept it because there is nothing else you can do.’

Cheyne demurred further, but as Price showed signs of retreating and leaving him to think it over until the evening, he hastily agreed to write the letter. Immediately the electric light came on in his cabin and Price passed in a couple of sheets of notepaper and envelopes. Cheyne gazed at them in surprise. They were of a familiar silurian gray and the sheets bore in tiny blue embossed letters the words ‘Warren Lodge, Dartmouth, S. Devon.’

‘Why, it’s my own paper,’ he exclaimed, and Price with a smile admitted that in view of some development like the present, his agents had taken the precaution to annex a few sheets when paying their call to Cheyne’s

‘If you will ask your manager to send the letter to Herbert Taverner, Esq., Royal Hotel, Weymouth, it will meet the case. Taverner is my agent, and as soon as it is in his hands I will set you ashore at Johnson’s wharf.’

Seeing there was no help for it, Cheyne wrote the letter. Price read it carefully, then sealed it in its envelope. Immediately after he handed through the panel a tumbler of whisky and water, then hurried off, saying he was going to despatch the letter and bring Cheyne his breakfast.

Oh, the unspeakable delight of that drink! Cheyne thought he had never before experienced any sensation approaching it in satisfaction. He swallowed it in great gulps, and when in a few moments Price returned, he demanded more, and again more.

His thirst assuaged, hunger asserted itself, and for the next half-hour Cheyne had the time of his life as Price handed in through the panel a plate of smoking ham and eggs, fragrant coffee, toast, butter, marmalade and the like. At last with a sigh of relief Cheyne lit his pipe, while Price passed in blankets and rugs to make up a bed in one of the bunks. Some books and magazines followed and a hand-bell, which Price told him to ring if he wanted anything.

Comfortable in body and fairly easy in mind, Cheyne made up his bed and promptly fell asleep. It was afternoon when he awoke, and on ringing the bell, Price appeared with a well-cooked lunch. The evening passed comfortably if tediously and that night Cheyne slept well.

Next day and next night dragged slowly away. Cheyne was well looked after and supplied with everything he required, but the confinement grew more and more irksome. However, he could not help himself and he had to admit he might have fared worse, as he lay smoking in his bunk and brooding over schemes to get even with the men who had tricked him.

About half-past ten on the second morning he suddenly heard oars approaching, followed by the sounds of a boat coming alongside and someone climbing on board. A few moments later Price appeared at the panel.

‘You will be pleased to hear, Mr Cheyne, that we have received the letter safely. We are getting under way at once and you will be home in less than three hours.’

Presently the motor started, and soon the slow, easy roll showed they were out in the open breasting the Channel ground swell. After a couple of hours Price appeared with his customary tray.

‘We are just coming into the estuary of the Dart.’ he said. ‘I thought perhaps you would have a bit of lunch before going ashore.’

The meal, like its fellows, was surprisingly well cooked and served, and Cheyne did full justice to it. By the time he had finished the motion of the boat had subsided and it was evident they were in sheltered waters. Some minutes later the motor stopped, the anchor was dropped and someone got into a boat and rowed off. A quarter of an hour passed and then the boat returned, and to Cheyne’s misgivings and growing concern, the motor started again. But after a very few minutes it once more stopped and Price appeared at the panel.

‘Now, Mr Cheyne, the time has come for us to say good-bye. For obvious reasons I am afraid we shall have to ask you to row yourself ashore, but the tide is flowing and you will have no difficulty in that. But before parting I wish to warn you very earnestly for your own sake and your own safety not to attempt to follow us or to set the police on our track. Believe me, I am not speaking idly when I assure you that we cannot brook interference with our plans. We wish to avoid “removals,”’ he lingered over the word and a sinister gleam came into his eyes, ‘but please understand we shall not hesitate if there is no other way. And if you try to give trouble there will be in your case no other way. Take my advice and be wise enough to forget this little episode.’ He took a small automatic pistol from his pocket and balanced it before the panel. ‘I warn you most earnestly that if you attempt to make trouble it will mean your death. And with regard to trying to follow us, please remember that this launch has the heels of any craft in the district and that we have a safe hiding-place not far away.’

As Price finished speaking he unlocked and threw open the cabin door, motioning his prisoner to follow him on deck. There Cheyne saw that they were far down the estuary, in fact, nearly opposite Warren Lodge and a mile or more from the town.

‘I thought you were going to take me to Johnson’s jetty,’ he remarked.

‘An obvious precaution,’ the other returned smoothly. ‘I trust you won’t mind.’

The freshness and the freedom of the deck were inexpressibly delightful to Cheyne after his long confinement in the stuffy cabin. He stood drawing deep draughts of the keen invigorating air into his lungs, as he gazed at the familiar shores of the estuary, lighted up in the brilliant April sunlight. Nature seemed in an optimistic mood and Cheyne, in spite of his experiences and Price’s gruesome remarks, felt optimistic also. He still felt he would devote all his energies to getting even with the scoundrels who had robbed him, but he no longer regarded them with a sullen hatred. Rather the view of the affair as a game in which he was pitting his wits against theirs gained force in his mind, and he looked forward with zest to turning the tables upon them in the not too distant future.

In the launch’s dinghy, which was made fast astern, was Lewisham, engaged in untying the painter of a second dinghy which bore on its stern board the words ‘S. Johnson, Dartmouth.’ The explanation of the starting and stopping of the motor now became clear. The conspirators had evidently gone in to pick up this boat and had towed it down the estuary so as to ensure their escape before Cheyne could reach the shore to lodge any information against them.

The painter untied, Lewisham passed it aboard the launch and Price, drawing the boat up to the gunwale, motioned Cheyne into it.

‘As I said, I’m sorry we shall have to ask you to row yourself ashore, but the run of the tide will help you. Good-bye, Mr Cheyne. I deeply regret all the inconvenience you have suffered, and most earnestly I urge you to regard the warning which I have given you.’

As he spoke he threw the end of the painter into the dinghy and the launch’s motor starting, she drew quickly ahead, leaving Cheyne seated in the small boat.

Full of an idea which had just flashed into his mind, the latter seized the oars and began pulling with all his might not for Johnson’s jetty, but for the shore immediately opposite. But try as he would, he did not reach it before the launch Enid had become a mere dot on the seaward horizon.

5

An Amateur Sleuth

Cheyne’s great idea was that instead of proceeding directly to the police station and lodging an information against his captors, as he had at first intended, he should himself attempt to follow them to their lair. To enter upon a battle of wits with such men would be a sport more thrilling than big game hunting, more exciting than war, and if by his own unaided efforts he could bring about their undoing he would not only restore his self-respect, which had suffered a nasty jar, but might even recover for Arnold Price the documents which he required for his claim to the barony of Hull.

Whether he was wise in this decision was another matter, but with Maxwell Cheyne impulse ruled rather than colder reason, the desire of the moment rather than adherence to calculated plan. Therefore directly a way in which he could begin the struggle occurred to him, he was all eagerness to set about carrying it out.