Полная версия

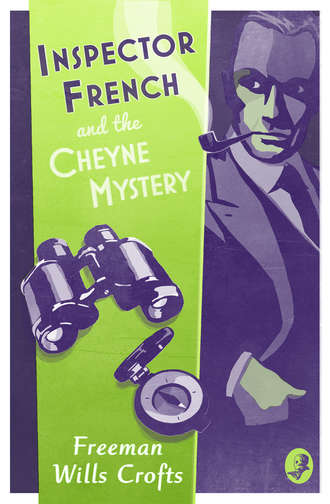

Inspector French and the Cheyne Mystery

The whole episode had a curious effect on Cheyne. It seemed, as he considered it, to lose its character of an ordinary breach of the law, punishable by the authorised forces of the Crown, and to take on instead that of a personal struggle between himself and these unknown men. The more he thought of it the more inclined he became to accept the challenge and to pit his own brain and powers against theirs. The mysterious nature of the affair appealed to his sporting instincts, and by the time he rejoined the sergeant in the study, he had made up his mind to keep his own counsel as to the Plymouth incident. He would call up the manager of the Edgecombe, tell him to carry on with his private detective, and have the latter down to Warren Lodge to go into the matter of the burglary.

He found the sergeant attempting ineffectively to discover fingerprints on the smooth walls of the safe, sympathised with him in the difficulty of his task, and asked a number of deliberately futile questions. On the grounds that nothing had been stolen he minimised the gravity of the affair, questioned his power to prosecute should the offenders be forthcoming, and instilled doubts into the other’s mind as to the need for special efforts to run them to earth. Finally, the man explaining that he had finished for the time being, he bade him good-night, locked up the house and went to bed. There he lay for several hours tossing and turning as he puzzled over the affair, before sleep descended to blot out his worries and soothe his eager desire to be on the track of his enemies.

3

The Launch ‘Enid’

For several days after the attempted burglary events in the Cheyne household pursued the even tenor of their way. Cheyne went back to Plymouth on the following morning and interviewed the manager of the Edgecombe, and the day after a quiet, despondent looking man with the air of a small shopkeeper arrived at Warren Lodge and was closeted with Cheyne for a couple of hours. Mr Speedwell, of Horton and Lavender’s Private Detective Agency, listened with attention to the tales of the drugging and the burglary, thenceforward appearing at intervals and making mysterious inquiries on his own account.

On one of these visits he brought with him the report of the analyst relative to the dishes of which Cheyne had partaken at lunch, but this document only increased the mystification the affair had caused. No trace of drugs was discernable in any of the food or drink in question, and as the soiled plates or glasses or cups of all the courses were available for examination, the question of how the drug had been administered—or alternatively whether it really had been administered—began to seem almost insoluble. The cocktail taken with Parkes before lunch was the only item of which a portion could not be analysed, but the evidence of the barmaid proved conclusively that Parkes could not have tampered with it.

But in spite of the analysis, the coffee still seemed the doubtful item. Cheyne’s sleepy feeling had come one very rapidly immediately after drinking the coffee, before which he had not felt the slightest abnormal symptoms. Mr Speedwell laid stress on this point, though he was pessimistic about the whole affair.

‘They know what they’re about, does this gang,’ he admitted ruefully as he and Cheyne were discussing matters. ‘That man in the hotel that called himself Parkes—if we found him tomorrow we should have precious little against him. However he managed it, we can’t prove he drugged you. In fact it’s the other way round. He can prove on our evidence that he didn’t.’

‘It looks like it. You haven’t been able to find out anything about him?’

‘Not a thing, sir; that is, not what would be any use. I can prove that he sent your telegram all right; the girl in the Post Office recognised his description. But I couldn’t get on to his trail after that. I’ve tried the stations and the docks and the posting establishments and the hotels and I can’t get a trace. But of course I’ll maybe get it yet.’

‘What about the address given on his card?’

‘Tried that first thing. No good. No one of the name known in the district.’

‘When did the man arrive at the hotel?’

‘Just after you did, Mr Cheyne. He probably picked you up somewhere else and was following you to see where you’d get lunch.’

‘Oh, well, that explains something. I was wondering how he knew I was going to the Edgecombe.’

‘It doesn’t explain so very much, sir. Question still is, how did he get all that other information about you; the name of your lawyer and so on?’

Cheyne had to admit that the prospects of clearing up the affair were not rosy. ‘But what about the burglary?’ he went on more hopefully. ‘That should be an easier nut to crack.’

Speedwell was still pessimistic.

‘I don’t know about that, sir,’ he answered gloomily. ‘There’s not much to go on there either. The only chance is to trace the men’s arrival or departure. Now individually the private detective is every bit as good as the police; better, in fact, because he’s not so tied up with red tape. But he hasn’t their organisation. In a case like this, when the police with their enormous organisation have failed, the private detective hasn’t a big chance. However, of course I’ve not given up.’

He paused, and then drawing a little closer to Cheyne and lowering his voice, he went on impressively: ‘You know, sir, I hope you’ll not consider me out of place in saying it, but I had hoped to get my best clue from yourself. There can be no doubt that these men are after some paper that you have, or that they think you have. If you could tell me what it was, it might make all the difference.’

Cheyne made a gesture of impatience.

‘Don’t I know that,’ he cried. ‘Haven’t I been racking my brains over that question since ever the thing happened! I can’t think of anything. In fact, I can tell you there was nothing—nothing that I know of any way,’ he added helplessly.

Speedwell nodded and a sly look came into his eyes.

‘Well, sir, if you can’t tell, you can’t, and that’s all there is to it.’ He paused as if to refer to some other matter, then apparently thinking better of it, concluded: ‘You have my address, and if anything should occur to you I hope you’ll let me know without delay.’

When Speedwell had taken his departure Cheyne sat on in the study, thinking over the problem the other had presented, but as he did so he had no idea that before that very day was out he should himself have received information which would clear up the point at issue, as well as a good many of the other puzzling features of the strange events in which he had become involved.

Shortly after lunch, then, on this day, the eighth after the burglary and drugging, Cheyne on re-entering the house after a stroll round the garden, was handed a card and told that the owner was waiting to see him in his study. Mr Arthur Lamson, of 17 Acacia Terrace, Bland Road, Devonport, proved to be a youngish man of middle height and build, with the ruggedly chiselled features usually termed hard-bitten, a thick black toothbrush moustache and glasses. Cheyne was not particularly prepossessed by his appearance, but he spoke in an educated way and had the easy polish of a man of the world.

‘I have to apologise for this intrusion, Mr Cheyne,’ he began in a pleasant tone, ‘but the fact is I wondered whether I could interest you in a small invention of mine. I got your name from Messrs Holt & Stavenage, the Plymouth ship chandlers. They told me you dealt with them and how keen you were on yachting, and as my invention relates to the navigation of coasting craft, I hoped you might allow me to show it to you.’

Cheyne, who had had some experience of inventors during six weeks special naval war service after his convalescence, made a non-committal reply.

‘I may tell you at once, sir,’ Mr Lamson went on, ‘that I am looking for a keen amateur who would be willing to allow me to fit the device to his boat, and who would be sufficiently interested to test it under all kinds of varying conditions. You see, though the thing works all right on a motor launch I have borrowed, I have exhausted my leave from my business, and am therefore unable to give it a sufficiently lengthy and varying test to find out whether it will work continuously under ordinary everyday sea-going conditions. If it proves satisfactory I believe it would sell, and if so I should of course be willing to take into partnership to a certain extent anyone who had helped me to develop it.’

In spite of himself Cheyne was impressed. This man was different from those with whom he had hitherto come in contact. He was not asking for money, or at least he hadn’t so far.

‘Have you patented the device?’ he asked, reckoning willingness to spend money on patent fees a test of good faith.

‘No, not yet,’ the visitor answered. ‘I have taken out provisional protection, which will cover the thing for four months more. If it promises well after a couple of months’ test it will be time enough to apply for the full patent.’

Cheyne nodded. This was a reasonable and proper course.

‘What is the nature of the device?’ he asked.

The young man’s manner grew more alert. He leaned forward in his chair and spoke eagerly. Cheyne frowned involuntarily as he recognised the symptoms.

‘It’s a position indicator. It would, I think, be useful at all times, but during fog it would be simply invaluable: that is, for coasting work, you know. It would be no good for protection against collision with another ship. But for clearing a headland or making a harbour in a fog it would be worth its weight in gold. The principle is, I believe, old, but I have been lucky enough to hit on improvements in detail which get over the defects of previous instruments. Speaking broadly, a fixed pointer, which may if desired carry a pen, rests on a moving chart. The chart is connected to a compass and to rollers operated by devices for recording the various components of motion one is driven off the propeller, others are set, automatically mostly, for such things as wind, run of tide, wave motion and so on. The pointer always indicates the position of the ship, and as the ship moves, the chart moves to correspond. Steering then resolves itself into keeping the pointer on the correct line on the chart, and this can be done by night without guide lamps, or in a fog, as well as in daytime. The apparatus would also assist navigation through unbuoyed channels over covered mud flats, or in time of war through charted mine fields. I don’t want to be a nuisance to you, Mr Cheyne, but I do wish you would at least let me show you the device. You could then decide whether you would allow me to fix it to your yacht for experimental purposes.’

‘I should like to see it,’ Cheyne admitted. ‘If you can do all you claim, I certainly think you have a good thing. Where is it to be seen?’

‘On my launch, or rather, the launch I have borrowed.’ The young man’s eagerness now almost approached excitement. His eyes sparkled and he fidgeted in his chair. ‘She is lying off Johnson’s boat slip at Dartmouth. I left the dinghy there.’

‘And you want me to go now?’

‘If you really will be so kind. I should propose a short run down the estuary and along the coast towards Exmouth, say for two or three hours. Could you spare so much time?’

‘Why, yes, I should enjoy it. I shall be back, say, between six and seven.’

‘I’ll have you back at Johnson’s slip at six o’clock. I have a taxi waiting now, and I’ll arrange with Johnson to call another for you as soon as he sees us coming up the estuary.’

‘I’ll go,’ said Cheyne. ‘Just a moment until I tell my people and get a coat.’

The day was ideal for the run. Spring was in the air. The brilliant April sun poured down from an almost cloudless sky, against which the sea horizon showed a hard, sharp line of intensest blue. Within the estuary it was calm, but multitudinous white flecks in the distance showed a stiff breeze was blowing out at sea. Cheyne’s spirits rose. It was a glorious sport, this of battling with the foaming, tumbling waves in the open. How he loved their blue-black depth with its suggestion of utter and absolute cleanness, the creamy purity of their seething crests, their steady, irresistible onward movement, the restless dancing and swirling of the wavelets on their flanks! To him it was life to feel the buoyant spring of the craft beneath him, to hear the crash of the bows into the troughs and the smack of the spindrift striking aft. He was glad this Lamson had called. Even if the matter of the invention was a washout, as he more than half expected, he felt he was going to enjoy his afternoon.

Three or four minutes brought them to Johnson’s boat slip on the outskirts of Dartmouth. There Lamson drew the proprietor aside.

‘See here,’ he directed, ‘we’re going out for a run. I want you to keep a lookout for us coming back. We shall be in about six. As soon as you see us send for a taxi and have it here when we get ashore. Now Mr Cheyne, if you’re ready.’

They climbed down into a small dinghy and Lamson, taking the oars, pulled out towards a fair-sized motor launch which lay at anchor some couple of hundred yards from the shore. She was not a graceful boat, but looked strongly built, showing a high bluff bow, a square stern and lines suggestive of speed.

‘A sea boat,’ said Cheyne approvingly. ‘You surely don’t run her by yourself?’

‘No, a motoring friend has been giving me a hand. I am skipper and he engineer. We hug the coast, you know, and don’t go out if it is blowing.’

As he spoke he pulled round the stern of the launch upon which Cheyne observed the words ‘Enid, Devonport.’ At the same time a tall, well-built figure appeared and waved his hand. Lamson brought up to the tiny steps aud a moment later they were on deck.

‘Mr Cheyne has come out to see the great invention, Tom. I almost hope that he is interested. My friend, Tom Lewesham, Mr Cheyne.’

The two men shook hands.

‘Lamson thinks he is going to make his fortune with this thing, Mr Cheyne,’ the big man remarked, smiling. ‘We must see that there is no mistake about our percentages.’

‘If you want a percentage you must work for it, my son,’ Lamson declared. ‘Mr Cheyne must be back by six, so get your old rattle-trap going and we’ll run down to the sea. If you don’t mind, Mr Cheyne, we’ll get under way before I show you the machine, as it takes both of us to get started.’

‘Right-o,’ said Cheyne. ‘I’ll bear a hand if there’s anything I can do.’

‘Well, that’s good of you. It would be a help if you would take the tiller while I’m making all snug. There’s a bit of a tumble on outside.’

The boat was certainly a flier. The charmingly situated old town dropped rapidly astern while Lamson ‘made snug.’ Then he came aft, shouted down through the engine-room skylight for his friend, and when the latter appeared told him to take the tiller.

‘Now, Mr Cheyne,’ he went on, ‘now comes the great moment! I have not fixed the apparatus up here in front of the tiller, partly to keep it secret and partly to save the trouble of making it weatherproof. It’s down in the cabin. But you understand it should be up here. Will you come down?’

He led the way down a companion to a diminutive saloon. ‘It’s in the sleeping part, still forward,’ he pointed, and the two men squeezed through a door in the bulkhead into a tiny cabin, lit by electric light and with a table in the centre and two berths on either side. On the table was a frame on the top of which was stretched a chart, and a light rod ran out from one side to a pointer fixed over the middle of the chart.

‘You can see that it’s very roughly made,’ Lamson went on, ‘but if you look closely I think you’ll find that it works all right.’

Cheyne bent forward and examined the machine, and as he did so mystification grew in his mind. The chart was not of the estuary of the Dart, nor, stranger still, was it connected to rollers. It was simply tacked on what he now saw was merely the lid of a box. How it was moved he couldn’t see.

‘I don’t follow this,’ he said. ‘How do you get your chart to move if it’s nailed down?’

There was no answer, but as he swung round with a sudden misgiving there was a sharp click. Lamson had disappeared and the door was shut!

Cheyne seized the handle and turned it violently, only to find that the bolt of the lock had been shot, but before he could attempt further researches the light went off, leaving him in almost pitch darkness. At the same moment a significant lurch showed that they were passing from the shelter of the estuary into the open sea.

He twisted and tugged at the handle. ‘Here you, Lamson!’ he shouted angrily. ‘What do you mean by this? Open the door at once. Confound you! Will you open the door!’ He began to kick savagely at the woodwork.

A small panel in the partition between the cabins shot aside and a beam of light flowed into Cheyne’s. Lamson’s face appeared at the opening. He spoke in an old-fashioned, stilted way, aping extreme politeness, but his mocking smile gave the lie to his protestations.

‘I’m sorry, Mr Cheyne, for this incivility,’ he declared, ‘and hope that when you have heard my explanation you will pardon me. I must admit I have played a trick on you for which I offer the fullest apologies. The story of my invention was a fabrication. So far as I am aware no apparatus such as I have described exists: certainly I have not made one. The truth is that you can do me a service, and I took the liberty of inveigling you here in the hope of securing your good offices in the matter.’

‘You’ve taken a’ bad way of getting my help,’ Cheyne shouted wrathfully. ‘Open the door at once, damn you, or I’ll smash it to splinters!’

The other made a deprecatory gesture.

‘Really I beg of you, Mr Cheyne,’ he said in mock horror at the other’s violence. ‘Not so fast, if you please, sir. I have an answer to both your observations. With regard to the door you will—’

Cheyne interrupted him with a savage oath and a fierce onslaught of kicks on the lower panels of the door. But he could make no impression on them, and when in a few moments he paused breathless, Lamson went on quietly.

‘With regard to the door, as I was about to observe, it would be a waste of energy to attempt to smash it to splinters, because I have taken the precaution to have it covered with steel plates. They are bolted through and the nuts are on the outside. I mention this to save you—’

Cheyne was by this time almost beside himself with rage. He expressed his convictions and desires as to Lamson and his future in terms which from the point of view of force left little to be desired, and persistently reiterated his demand that the door be opened as a prelude to further negotiation. In reply Lamson shook his head, and remarking that as the present seemed an inopportune moment for discussing the situation, he could postpone the conversation, he closed the panel and left the inner cabin once more in darkness.

For an hour Cheyne stormed and fumed, and with pieces which he managed to knock off the table tried to break through the door, the bulkheads and the deadlighted porthole, all with such a complete absence of success that when at last Lamson appeared once more at the panel he was constrained to listen, though with suppressed fury, to what he had to say.

‘You see, it’s this way, Mr Cheyne,’ the erstwhile inventor began. ‘You are completely in our power and the sooner you realise it and let us come to business, the sooner you’ll be at liberty again. We don’t wish you any harm; please accept my assurances on that. All we want is a slight service at your hands, and when you perform it you will be free to return home; in fact we shall take you back as I said, with profuse apologies for your inconvenience and loss of time. But it is only fair to point out that we are determined to get what we want, and if you are not prepared to come to terms now we can wait until you are.’

Cheyne, still at a white heat, cursed the other savagely. Lamson waited until he had finished, then went on in a smooth, almost coaxing tone:

‘Now do be reasonable, Mr Cheyne. You must see that your present attitude is only wasting time for us both. Not to put too fine a point on it the situation is this: You are there, and you can’t get out, and you can’t attract attention to your predicament—that is why the deadlights are shipped. It grieves me to say it,’ Lamson smiled sardonically, ‘but I must tell you that you will stay there until you do what we want. In order to prevent Mrs Cheyne becoming uneasy we shall wire her in your name that you have left for an extended trip and won’t be back for some days. “To Cheyne, Warren Lodge, Dartmouth. Gone for yachting cruise down French coast. Address Poste Restante, St Nazaire. All well. Maxwell.” You see, we know exactly how to word it. All suspicion would be lulled for some days and then,’ he paused and something sinister and revolting came into his face, ‘then it wouldn’t matter, for it would be too late. For you see there is neither food nor drink in the cabin and we don’t propose to pass any in. You won’t get any, Mr Cheyne, no matter how many days you remain aboard: that is,’ his manner changed, ‘unless you are reasonable, which of course you will be. In that case no harm is done. Now won’t you hear our little proposition?’

‘I’ll see you in hell first,’ Cheyne shouted, his rage once again overwhelming him. ‘You’ll pay for this, I can tell you. It’ll be the dearest trip you ever had in your life,’ and he proceeded with threats and curses to demand the immediate opening of the door. Lamson, a whimsical smile curling his lips, shrugged his shoulders at the outburst, and replied by withdrawing his head from the opening and sliding the panel to.

Cheyne, left once more in almost complete darkness, sat silent, his mind full of wrath against his captors. But as time passed and they made no sign his fury somewhat evaporated and he began to wonder what it was they wanted with him. His rage had made him thirsty, and the mere fact that Lamson had stated that nothing would be given him to drink, made his thirst more insistent. It was impossible, he said to himself, that the scoundrels could carry out so diabolical a threat, but in spite of his assurance, little misgivings began to creep into his mind. At all events the vision of his usual cup of afternoon tea grew increasingly alluring. When therefore after what seemed to him several hours, but what was in reality about forty minutes only, the panel suddenly opened, he admitted sullenly that he was prepared to listen to what Lamson had to say.

‘That’s good,’ the young man answered heartily. ‘If you could just see your way to humour us in this little matter there is no reason why we should not part friends.’

‘There’s no question of friends about it,’ Cheyne declared sharply. ‘Cut your chatter and get on to business. What do you want?’

A smile suffused Mr Lamson’s rough-hewn countenance.

‘Now that’s talking,’ he cried. ‘That’s what I’ve been hoping to hear. I’ll tell you the whole thing and you’ll see it’s only a mere trifle that we’re asking. I can put it in five words: We want Arnold Price’s letter.’

Cheyne stared.

‘Arnold Price’s letter?’ he repeated in amazement. ‘What on earth do you know about Arnold Price’s letter?’

‘We know all about it, Mr Cheyne—a jolly sight more than you do. We know about his giving it to you and the conditions under which he asked you to keep it. But you don’t know why he did so or what is in it. We do, and we can justify our request for it.’

The demand was so unexpected that Cheyne sat for a moment in silence, thinking how the letter in question had come into his possession. Arnold Price was a junior officer in one of the ships belonging to the Fenchurch Street firm in whose office Cheyne had spent five years as clerk. Business had brought the two young men in contact during the visits of Price’s ship, and they had become rather friendly. On Cheyne’s leaving for Devonshire they had drifted apart, indeed they had only met on one occasion since. That was in 1917, shortly before Cheyne received the wound which invalided him out of the service. Then he found that his former companion had volunteered for the navy on the outbreak of hostilities. He had done well, and after a varied service he had been appointed third officer of the Maurania, an eight-thousand ton liner carrying passengers, as well as stores from overseas to the troops in France. The two had spent an evening together in Dunkirk renewing their friendship and talking over, old times. Then, two months later, had come the letter. In it Price asked his friend to do him a favour. Some private papers, of interest only to himself, had come into his possession and he wished these to be safely preserved until after the war. Knowing that Cheyne was permanently invalided out, he was venturing to send these papers, sealed in the enclosed envelope, with the request that Cheyne would keep them for him until he reclaimed them or until news of his death was received. In the latter case Cheyne was to open the envelope and act as he thought fit on the information therein contained.