Полная версия

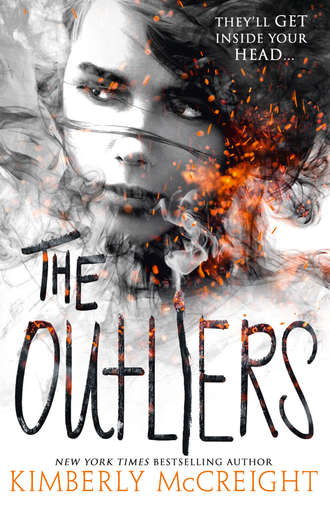

The Outliers

“Couldn’t Cassie just still be out then?” my dad asks. “It’s only dinnertime.”

“She was supposed to be home,” Karen says firmly. “She was grounded this whole week. Because she—well, I don’t even want to tell you what she called me.” And there it is. The tone. The I-hate-Cassie-a little-bit, maybe even more than she hates me. “I told her if she wasn’t home, I really was going to put a call into this boarding school I’d been looking into—you know, one of those therapeutic ones. And no, I’m not proud of that threat. That we’ve sunk as low as me shipping her off. But we have, that’s the honest truth. Anyway, I also found this.”

Karen fishes something out of her pocket and hands it to my dad. It’s Cassie’s ID bracelet.

“She hasn’t taken that bracelet off since the day I gave it to her three years ago.” Karen’s eyes fill with tears. “I didn’t even really mean it about that stupid school. I was just so worried. And angry. That’s the truth. I was angry, too.”

My dad looks down quizzically at the bracelet looped over his fingers, then at Karen again. “Maybe it fell off,” he says, his voice lifting like it’s a question.

“I found it on my pillow, Ben,” Karen says. “And it wasn’t there this morning. So Cassie must have come back at some point and left again. It was meant as a sign—like a ‘screw you, I’m out of here.’ I know it.” Karen turns to me then. “You haven’t heard from her, have you, Wylie?”

Back when things were still okay between us, Cassie and I wouldn’t have gone more than an hour without at least texting. But that’s not true anymore. I shake my head. “I haven’t talked to her in a while.”

It’s been a week at least, maybe longer. Being at home, it’s easy to lose track of the exact number of days. But it’s the longest stretch since the accident that we’ve gone without talking. It was bound to happen eventually: we couldn’t be pretend-friends forever. Because that’s all we were really doing when Cassie came back after the accident: pretending.

The accident happened in January, but Cassie and I had stopped talking the first time right after Thanksgiving. Nearly two long months, which, let’s face it, might as well be a lifetime when you’re sixteen. But the morning after the accident, Cassie had just showed up on our doorstep. My eyes had been burning so badly from crying that I’d thought I was seeing things. It wasn’t until Cassie had helped me change out of the clothes I’d been dressed in for two days that I began to believe she was real. And it wasn’t until after she’d pulled my hair out of its ragged, twisted bun, brushed it smooth, and braided it tight—like she was arming me for battle—that I knew how badly I needed her to stay.

I don’t know what Cassie has told Karen about our best-friend breakup and our temporary get-back-together. And it ended anyway a few weeks ago. But I can bet it’s not much. The two of them aren’t exactly close. And it’s not like the reasons we stopped talking reflect so well on Cassie.

“You haven’t talked to Cassie in a while?” my dad asks, surprised.

My mom knew about Cassie and me having a falling-out back when it first happened. She apparently just never told him. It is possible that I asked her not to—I don’t remember. But I do remember the day I told my mom that Cassie and I weren’t friends anymore. We were lying side by side on her bed, and when I was done talking, she said, “I would always want to be your friend.”

I shrug. “I think the last text I got from her was last week? Maybe on Tuesday.”

“Last week?” my dad asks, eyebrows all scrunched low.

The truth was, I really wasn’t sure. But it was the following Thursday now. And it was definitely at least a week since we’d spoken.

“Oh, that long.” Karen is more disappointed than surprised. “I noticed that the two of you hadn’t been talking as much, but I didn’t realize …” She shakes her head. “I called the police, but of course because Cassie’s sixteen and we’ve been fighting they didn’t seem in a big rush to go after her. They filed a report and they’ll check the local hospitals, but they’re not going to start combing the woods or anything. They’ll send a car out looking, but not until the morning.” Karen presses her fingertips against her temples and rocks her head back and forth. “Morning. That’s twelve hours from now. Who knows who Cassie will be with or what shape she’ll be in by then? Think of all the horrible— Ben, I can’t wait until morning. Not with the way she and I left things.”

I’m surprised that Karen seems to know even partly how out of control Cassie has gotten. But then, without me to help cover for her, Cassie was bound to get busted eventually. And this scenario Karen has in her head—Cassie well on her way to passed out somewhere—isn’t crazy. Even at that hour, just before seven p.m., it’s possible.

“Nooners,” the kids at Newton Regional called them. Apparently getting totally wasted in the middle of the day was what all the cool kids were doing these days. The last time I rushed out to help Cassie back in November, it was only four or five in the afternoon. I had to take a cab to pick her up at a party at Max Russell’s house, because she was way too drunk to get home on her own. Lucky for her, my mom had been traveling, my dad had been, like always, working at his campus lab on his study, and Gideon was still at school, working late on his Intel Science Competition application. I slipped out and we slipped back in with no one ever the wiser, Cassie bumping into walls as she swayed. After, I held her hair back over the toilet when she threw up again and again. And later I called Karen to say she had a migraine and wanted to stay the night.

I told Cassie the next morning that she needed to stop drinking or something terrible would happen. But by then I wasn’t her only friend. I was just the one telling her the things she didn’t want to hear.

“Are you okay, Wylie?” My dad is staring at me. And he’s been staring at me for who knows how long. I realize then why. I’ve got myself pressed hard up against the back wall of the living room like I’m trying to escape through the plaster. “Why don’t you sit down?”

“I’m fine,” I say. But I do not sound fine.

“Oh, honey, I’m sorry.” Karen looks at me, seems again like she might cry. “The last thing all of you need is my, is our—” She forces a wobbly smile, looks even closer to falling apart. I stare down. If I see her really start to lose it, I will too. “Cassie will be fine, Wylie, I’m sure. The police are probably right that I’m overreacting. I can have a bit of a short fuse for this kind of …”

She doesn’t finish her sentence. Because of Cassie’s dad, Vince, that’s what she means. Cassie’s parents were already divorced when we met, but Cassie told me all about life before. And Vince was never a quiet drunk. Fights with neighbors at summer barbecues, calling home to be rescued from whatever latest bar he’d been tossed out of. But the final straw was the second DUI, the one where he’d crashed his car into a mailbox downtown. Karen is as afraid of Vince’s history repeating itself in Cassie as I’ve been. When I glance up from the carpet, my dad is still looking at me.

“I’m fine,” I say again, but too loud. “I just want to help find Cassie.”

“Wylie, of course you want to help,” my dad starts. “But right now, I don’t think you—”

“Please,” I say, willing my voice to sound determined, not desperate. Desperate is not my friend. “I need to do this.”

And I do. I don’t realize how bad until the words are out of my mouth. Partly because I want to prove to myself that I can. But also, I do feel guilty. I didn’t agree with the things Cassie was doing, was scared about what might happen to her if she didn’t stop. But maybe I should have made more sure that she knew I’d always love her no matter what mistakes she made.

“It was so selfish of me to come here.” Karen rests her forehead against her hand. “After everything all of you have been through—I wasn’t thinking clearly.”

My dad’s eyes are on mine. Narrowed, like he’s assessing some tricky quadratic equation. Finally, he takes a deep breath.

“No, Wylie is right. We want to help. We need to,” he says. And my heart soars. Maybe he can hear me after all. Maybe he does understand a little bit of something. He turns back to Karen. “Let’s back up. What exactly happened this morning?”

Karen crosses her arms and looks away. “Well, we were rushing around getting ready, and Cassie and I were snapping at each other as usual, because she wouldn’t get out of bed. She’s missed the bus five times in the last two weeks. And I had to be somewhere this morning and I couldn’t—” Her voice tightens as she pulls a crumpled tissue out of her pocket. “Anyway, I totally lost my patience. I—I screamed at her, Ben. Completely let her have it. And she called me the most horrible word. One that I won’t repeat. A word that I have never in my life said out loud. But there was Cassie calling me that.” Her voice catches again as she stares down at her fingers, twisting the bunched tissue between them. “So I told her I was finally going to call that boarding school and have them cart her away. So they could scare some sense into her.”

My dad nods like he knows exactly what Karen means. Like he’s yelled the exact same kind of thing at me countless times. But the only time I can remember him ever yelling at me about anything was one Fourth of July at Albemarle Field when I was barefoot at the fireworks and almost stepped on a broken chunk of bottle.

“The worst part is that what started it—my big rush—wasn’t even about a work meeting or an open house or a prospective client. Nothing I needed to do to put food on our table. Nothing that actually mattered.” Karen looks up, toward the ceiling. Like she’s searching for an answer up there. “It was a yoga class. That’s why I lost it.” She looks at my dad like maybe he can explain her own awfulness. “I fought Vince through the entire divorce for Cassie to live with me, so I could be there for her, and now—I am so selfish.”

Karen drops her face in her hands and rocks it back and forth. I can’t tell if she’s crying, but I really wish she wouldn’t. Because I am worried about Cassie. But not that worried. Ironic that I—of all people—would ever be less worried than anyone else. Makes me feel like maybe I’m in denial. And whatever it is could definitely be bad. Would any of the people Cassie hangs out with these days really call for help if she needed it? Would they stay to make sure she didn’t vomit in her sleep, that no one took advantage of her while she was passed out cold? No. The answer on all fronts is no.

“Karen, you can’t do this to yourself. No one is perfect.” My dad steps toward her and leans in like he might actually put a hand on her back. But he crosses his arms instead. “Was Cassie absent from school?”

“There was no message from them. But I guess—” Karen twists her tissue some more. “Cassie could have deleted it when she came back to leave the bracelet. She did that a couple weeks ago when she skipped school. I was going to change the school contact number to my cell, but I forgot.”

Cassie’s been skipping school, too? These days there is so much about her I don’t know.

“Why don’t you try texting her now, Wylie?” my dad suggests. “Maybe hearing from you—you never know.”

Maybe she’s just not answering Karen. He doesn’t say that, but he’s thinking it. And after Karen threatened her with that boarding school boot camp, Cassie might never talk to her again. But then if she’s avoiding her mom, she’ll probably avoid me, too, for the exact same reason: we both make her feel bad about herself.

“Okay, but I don’t know …” I pull my phone out of my sweatshirt pocket and type, Cassie, where r u? Your mom is freaking. I wait and wait, but she doesn’t write back. Finally, I hold up my phone. “It can take her a minute to respond.”

Actually, it never does. Or never did. The Cassie I knew lived with her phone in her hand. Like it was a badge of honor to respond to every tweet or text or photo within seconds. Or maybe it was more of a life vest. Because the skinnier and drunker and more popular Cassie got, the more desperate she seemed.

“Can you think of anywhere Cassie might be, Wylie?” Karen asks. “Or anyone she could be with?”

“You tried Maia and those guys?” I ask, hating the feel of her name in my mouth.

The Rainbow Coalition: Stephanie, Brooke, and Maia—still best friends after all these years. All except me. They started calling themselves the Rainbow Coalition freshman year because of their array of hair colors. (And they seemed not to care that their all being white made their nickname totally offensive.) More beautiful than ever, they’d also gotten much cooler. By junior year, Maia, Brooke, and Stephanie had clawed their way to the top of the Newton Regional High School popularity pile. Cassie had always hated the Rainbow Coalition for what they’d done to me, right up until they reached down and invited her to climb up and join the pile.

“Maia and those girls.” Karen rolls her eyes. “I honestly don’t know what Cassie sees in them.”

That they see her, I want to say. In a way you never did. But then, I’m hardly one to talk. At the beginning, Cassie tried to hide how proud she was that she’d been invited to join the Rainbow Coalition at one of their “hangouts.” Not “parties,” because that would be “so basic.” (And yes, they actually talk like that.) She pretended that she was doing it for research purposes only. It was at the very first Rainbow Coalition “hangout” that Cassie met Jasper. And after that, she seemed to care a whole lot less about pretending anything.

It was exciting for her. I did get that part. But I also thought Cassie would get over it pretty fast, that she’d come to her senses. Instead, she just got more and more drunk at more and more parties. More than once, I played back to her what she had always told me about her dad: that she never wanted to end up like him. I told her again and again that, as her friend, I was worried. But what did she need me for when all I did was make her feel bad about herself? She had the Rainbow Coalition to fill her days and, at night, she was falling in love, hard. I could see it, but I was trying hard to pretend it wasn’t happening. Because Jasper Salt didn’t lift Cassie out of the gutter the way a real friend would, the way someone who really cares about you does. No, he grabbed Cassie’s hand and leaped with her right down the drain.

“You know, Jasper really is a good person, Wylie,” Cassie had started in the Monday after Thanksgiving. “You need to get to know him.”

We were eating lunch at Naidre’s, the one coffee shop near school where upperclassmen were allowed to go off campus. Soup and a sandwich for me, a dry bagel for Cassie, which she was busy tearing into small pieces and rearranging on her plate so it seemed like she was eating.

We’d only been together five minutes after not seeing each other for four days and already we were back in a fight. But really, things had been off between us since Cassie came home from fitness summer camp at the end of August. “Fat camp,” Cassie had called it when her mother had forced her to go the summer before eighth grade. But this time had been Cassie’s idea. Even though it was hard to see how she had any more weight to lose. When she got home, she was absolutely skeletal, a comparison that delighted her.

It wasn’t just the weight loss, either. Cassie also had new hair, longer and blown straight, and stylish clothes. It was hard to believe she was the same person who’d hunched over that toilet with me. I wasn’t surprised weeks later when the Rainbow Coalition had come knocking or even that somebody like Jasper—popular, good-looking, an athlete (and an asshole)—had noticed Cassie. I just couldn’t believe how much she’d liked them back.

“I know everything about Jasper that I need to know,” I said, then burned my mouth on my tomato soup.

Rumor was he had knocked some senior out with a single punch his freshman year. In one version, Jasper had broken the kid’s nose. I still couldn’t figure out why he wasn’t in jail, much less still in school. But I hadn’t liked Jasper even before I’d heard about that punch, and maybe some of those reasons were shallow—his body-hugging T-shirts, his swagger, and his stupid, put-on surfer lingo. But I also had proof that he was an actual asshole. I had Tasha.

Tasha was our age but seemed way younger. She hugged people without warning and laughed way too loud, always wearing pink or red with a matching headband. Like a giant Valentine’s Day card. But no one was ever mean to Tasha; that would have been cruel. No one except for Jasper, that is. A couple of weeks after he and Cassie started hanging out—the beginning of October—I saw Jasper talking to Tasha down at the end of an empty hall. They were too far away to hear, but there was no mistaking Tasha rushing back my way in tears. But when I told Cassie about it afterward, she just said Jasper would never do something mean to Tasha. Which meant, I guess, that I was lying.

“Jasper might not be perfect, but he’s had a really hard life. You should cut him a break,” Cassie went on now, readjusting her bagel scraps. “It’s just him and his mom, who’s totally selfish, and his older brother, who’s a huge asshole. And his dad’s in jail,” she added defensively, but also kind of smugly. Like Jasper’s dad being a criminal was somehow proof that he was a good person.

“In jail for what?”

“I don’t know,” she snapped.

“Cassie, what if it’s something really bad?”

“Just because Jasper’s father did something doesn’t mean there’s something wrong with him. It’s actually really messed up that you would even think that.” Cassie shook her head and crossed her arms. The worst part was that she was right: it was pretty awful that my mind had jumped there. “Besides, Jasper understands me. That matters more than his stupid dad.”

I felt a flash of heat in my chest. So here it was, the real truth: Jasper understood her and I did not.

“Which you, Cassie?” I snapped. “You have so many faces these days, how can he even keep track?”

Cassie stared at me, mouth hanging open. And then she started gathering her things.

“What are you doing?” I asked, my heart beating hard. She was supposed to get angry. We were supposed to have a fight. She wasn’t supposed to disappear.

“I’m leaving,” Cassie said quietly. “That’s what normal people do when someone is awful to them. And in case you’re confused, Wylie”—she motioned to herself—“this is normal. And you are awful.”

“Anyway, I did speak to Maia and the other girls,” Karen goes on. “They said they last saw Cassie in school, though none of them could seem to remember exactly when.”

“Have you talked to Jasper?” I ask, trying not to sound like I’ve already decided that he is—in spirit if not in fact—100 percent responsible for every bad thing that has ever happened to Cassie.

Karen nods. “He exchanged texts with Cassie when she was on the bus on her way to school, but that’s the last time he heard from her. At least, supposedly.” She squints at me. “You don’t like Jasper, do you?”

“I don’t really know him, so I’m not sure my opinion means anything,” I say, even though I think just the opposite.

“You’re Cassie’s oldest friend,” Karen says. “Her only real friend, as far as I’m concerned. Your opinion means everything. You don’t think he would hurt her, do you?”

Do I think that Jasper would actually do something to Cassie? No. I think many bad things about Jasper, but I have no reason to think that. I do not think that.

“I don’t know,” I say, being vague on purpose. But I can’t even half accuse Jasper of something that serious just because I don’t like him. “No, I mean. I don’t think so.”

“And Vince hasn’t heard from her either?” my dad asks.

“Vince,” Karen huffs. “He’s hanging out with some new ‘girlfriend’ in the Florida Keys. Last I heard he was going to try to get his private detective’s license. Ridiculous.”

The insane part is that Cassie might actually call her dad. Cassie is crazy about Vince, despite everything. They email and text all the time. It’s their distaste for Karen that unites them.

“You should probably try to reach him,” my dad suggests gently. Then he heads over to the counter, picks up his wallet, and peers at the little hooks on the wall where we hang our keys. “Just in case. And you and I will go out looking for her.”

Karen nods as she looks down at her fingers, still working them open and closed around the mostly shredded tissue.

“He’s going to blame me, you know. Like if I wasn’t such a hateable hardass, Cassie would still be—” Karen clamps her hand over her mouth when her voice cuts out. “And he’ll be right. That’s the worst part. Vince has problems, but he and Cassie—” She shakes her head. “They always connected. Maybe if I—”

“Nothing is that simple. Not with kids, not with anything,” my dad says as he finally finds his keys in a drawer. “Come on, let’s stop back at your place first. Make sure there’s no sign of Cassie there. We’ll call Vince on the way. I’ll even talk to him if you want.” My dad steps toward the front door but pauses when he notices Karen’s feet. “Oh, wait, your shoes.”

“That’s okay,” she says with an embarrassed wave of her hand. Even now, trying to reclaim a small scrap of perfect. “I’ll be fine. I drove here this ridiculous way. I can get back home.”

“What if we end up having to stop someplace else? No, no, you need shoes. You can borrow a pair of Hope’s.”

Hope’s? So casually, too, like he didn’t just offer Karen a sheet of my skin. Of course, it’s not like he can offer Karen a pair of my spare shoes. After a panic-fueled anti-hoarder’s episode after the funeral, I only have one pair of shoes left. The ones I’m wearing. But it’s the way my dad said it: like it would be nothing to give away all my mom’s things.

Sometimes I wonder if my dad had stopped loving my mom even before she died. I have evidence to support this theory: their fight, namely. After an entire life of basically never a mean word between them, they had suddenly been at each other constantly in the weeks before the accident. And not really loving her would definitely explain why he hasn’t seemed as broken up as me in the days since she died.

Don’t do it, I think as he moves toward the steps for her shoes. I will never forgive you if you do. Luckily, he stops when his phone buzzes in his hand.

He looks down at it. “I’m sorry, but this is Dr. Simons.” Saved by my dad’s only friend: Dr. Simons. The one person he will always drop everything for. That never bothered me before. But right now, it is seriously pissing me off. “Can you take Karen upstairs, Wylie? See if there’s something of your mom’s that will fit her?”

I just glare at him.

“Are you okay?” he asks, when I still don’t move. His face is tight.

“Yeah,” I say finally, because he’ll probably use me being angry as more proof that we shouldn’t be helping Karen. “I’m awesome.”

But the whole way upstairs, I still try to think of an excuse not to give Karen the shoes. One that doesn’t seem crazy. One that my mom would approve of. Because my mom would want me to give Karen whatever she needs. You can do it, she’d say if she was there. I know you can.

Soon enough, Karen is behind me in my parents’ room as I stand frozen in front of their closet. We’re only lending them, I remind myself, as I pull open the closet door and crouch down in front of my mom’s side of the closet. I close my eyes and try not to take in her smell as I feel around blindly for her shoes. Finally, my hands land on what I think are a pair of low dress boots that my mom only wore once or twice. But I feel sick when I open my eyes and see what I’ve pulled out instead. My mom’s old Doc Martens, the ones she loved so much she had the heels replaced twice.