Полная версия

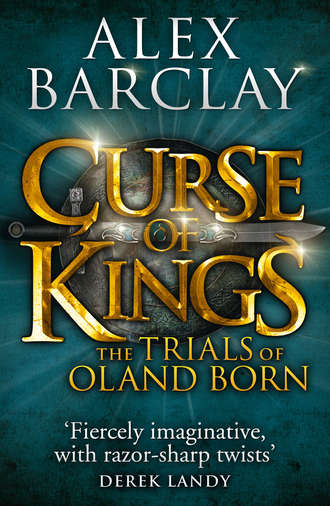

Curse of Kings

Roxleigh’s very best friend was a Derrington man called Rowe, who was as tall as Roxleigh, but moved, as he would himself admit, “with more ballast”. His canted walk was no match for Roxleigh’s loping stride, and he would bound behind him like a giant puppy. Rowe spoke from his warm heart and shining mind, his head swooping down, then up with a flourish at the end of each burst of inspiration. And he had many, as did Roxleigh. Both fiercely intelligent, they were part of a small group of great thinkers who met every month in The Derrington Inn to discuss matters of importance in the Kingdom of Decresian, always with the intention of enhancing the life of its people.

But in the year before he was carried, wailing and flailing, from the castle, something had changed in Prince Roxleigh. Rowe, from whom he had been inseparable, had vanished from Derrington quite suddenly. Roxleigh had begun to pace the dungeon hallways of the arena at night, talking of beasts and monsters, of dark creatures with secret chambers, scribbling his notions on reams of paper that he stacked to the ceiling in the musty cells.

From then until now, if you were called ‘roxley’ or ‘roxling’ or if your actions were deemed ‘roxworthy’, the message was clear: you were as mad as the mad prince that was locked away in the madhouse. Years later, when Roxleigh’s younger brother, Prince Stanislas – King Micah’s father – became King of Decresian, a messenger arrived at the castle to say that Prince Roxleigh did not mind one bit. But everyone agreed: Roxleigh had no mind with which to mind.

Oland left Viande and the sleeping beasts of The Craven Lodge behind. As he walked, he pondered the story of Prince Roxleigh. The year leading up to his descent into madness had been a bleak one for the kingdom, when a bermid-ant plague struck the northern coast. The small black ants moved south, ravaging the land, turning the rich vegetation from vibrant green to barren bronze. No one had ever seen such a beautiful trail of destruction. The bermids poisoned crops and the animals that fed on them. The people of Envar died from eating the produce of the land, the meat of diseased livestock, or they died from eating neither.

Prince Roxleigh’s father, King Seward, a kind, strong leader, vowed to the surrounding territories that he would do everything he could to contain the plague within Decresian’s borders. Yet, despite the best efforts of this honourable king, it was not to be, and the plague spread.

Almost one hundred years had passed since Roxleigh and Rowe had last walked the plague-ravaged ground to the village market, ground that had eventually been restored, only to be ravaged again by neglect. It was as if, from the parapets of Castle Derrington, The Craven Lodge had thrown a grey veil over the whole of Decresian.

Oland had one stall to visit in Merchants’ Alley – that of the butcher, Malachy Graham. It was Oland’s fourth visit that week and it was not just for meat for The Craven Lodge.

“Your leg of lamb,” said Malachy, but, as he reached under the stall, he stopped when a voice rose over the bustle of the market.

“The Great Rains are nigh! The Great Rains are nigh!”

The crowd parted and allowed the shouting man through. He looked to be in his sixties, his hair grey and his face battered by the elements, lined by suffering, sunken by hunger. His pale, doleful eyes were sparking with panic. Between cries, his lips were pursed and trembling. He was dressed in a long, faded blue robe. The ties at the neck hung loose, exposing his bony chest and a scattering of wispy hair. Over his robe, he wore a beautiful, pristine sheepskin. Oland had seen the man before and heard his wild preachings about the impending return of The Great Rains.

“He’s roxley!” laughed the butcher’s young son, sticking his head up from behind the stall.

Malachy laid his hand on the boy’s shoulder. “Daniel, I don’t ever want to hear you say that again,” he said. “Great tragedy lies behind that man’s ramblings, and it is no surprise that his mind broke under the weight of it.”

“But Father! The Great Rains are over!” said Daniel. “Everyone knows that.”

“The Great Rains are nigh!” shouted the rambling man again as he disappeared into the crowd ahead.

Daniel laughed.

Malachy leaned down to him. “Son, some people’s minds travel back to the past and are forever trapped there. We need to care for them, not mock them.” He was wrapping slices of ham as he spoke. He handed the package to his son. “Go after the man, and give him this. His name is Magnus Miller. Call him by his name.”

Daniel was open-mouthed.

“He won’t bite,” said Malachy. He smiled as he turned back to Oland. Then his face darkened. “I wish I could threaten him with no trip to The Games tonight, but who am I to overrule the decrees of The Craven Lodge?”

Oland nodded. He had no desire to go to The Games either, but, as The Craven Lodge’s servant, he had no choice. “I should get back to the castle,” he said.

Malachy lowered his voice. “Before you go, you need to know that there are already whisperings around the village about the final round, Oland. One of the soldiers has been talking…”

Oland raised his eyebrows. “What has he said?”

“Well, what you told me: that instead of King Micah’s final round, Acuity, a test of sharpness of mind, Villius’ final round is to be called Agility and that it’s more about the sharpness of a blade.”

Oland took in a breath. “Has he said any more than that?”

Malachy shook his head. “No, but no one needs a fool soldier to tell them that the final round will be a bloody one. It’s Villius Ren – it will be designed not just to bring a contender the dishonour of defeat, but to bring him the dishonour of a savage and public demise.”

He reached under the stall. “The lamb,” he said. He slid another thick package underneath it as he handed it over. “And the rest…”

“Thank you,” said Oland. He turned to leave, then glanced back. “Do you know anyone competing?”

“Two of my nephews were taken by The Lodge from their homes last night,” said Malachy. “‘To make up numbers’ they were told. A neighbour’s son is competing willingly, believing the promises of land and glory that we both know will never come… no matter how many medals hang from his neck.”

“I wish them well,” said Oland.

Oland hurried back to Castle Derrington, first to the kitchen, then to the dungeons beneath the arena and the same dark hallways the troubled Prince Roxleigh had paced. As Oland passed the cramped cells, lions, tigers and leopards moved towards him, swiping at the bars that had imprisoned them for weeks. Oland’s task was to starve them ahead of the Agility round, when they were to be unleashed for a man-versus-beast battle to satisfy Villius’ bloodlust.

He unwrapped the second package Malachy Graham had given him, revealing the bloody steaks that would quiet the animals’ hunger and tame their angry spirits.

Oland sat in the corner as the animals ate. He was reading a play called The Banon Servant, about a servant boy who bravely faced his master’s taunts. Oland wished he had his courage and was eager to read what became of him. The light in the dungeon suddenly dimmed. Oland pushed the play back into his bag. In the entrance ahead, Villius Ren stood blocking out the sun.

“Get over here,” he roared. As Villius walked down the steps, the light again streamed in. Barely breaking his stride, he slapped Oland across the face.

“You will never run from me again,” said Villius.

Oland nodded.

“Speak!” said Villius. “Find your tongue! There’s nothing more pathetic than a cowering mute.” But he didn’t even wait to hear Oland. “Now, show me the starving monsters you have made me…”

Oland’s heart pounded. Barely half an hour had passed since the animals had eaten their largest meal of the week. They were curled up and resting in the back of their cells. Oland’s hands were still stained with the blood of the meat he had fed them.

Villius Ren walked past the cells, studying each animal. He rattled some of the bars, and got little response.

“They are weak with hunger,” said Oland.

“They should react,” spat Villius.

“There are bars between you,” said Oland. “They know that it’s pointless to attack.”

In a flash, Villius grabbed Oland by the wrists and held up his palms.

“Weak with hunger…” said Villius. As he spoke, each word was lengthened, its delivery darkly mocking. “Yes. That explains why a ravenous beast wouldn’t rush to feast on the blood-stained hands of a foolhardy boy.”

He flung Oland’s hands from his grip. “I’ll have Viande slaughter these worthless beasts… and you will help him.” He raised his eyebrows. “Have you nothing to say?”

“I… I’m sorry,” said Oland.

“I… I… I…” spat Villius, pushing his face closer and closer to Oland’s. “Ha! Look at you – you’re paler than Wickham.” If Villius could insult more than one person at a time, it gave him great pleasure.

He spun around and walked away, leaving Oland staring after him, deeply ashamed of the single trickle of cold sweat that ran down his side.

The voice of Villius Ren boomed from above.

“Guards, for our final round, remove the females from the arena.”

The crowd was silenced by his feigned chivalry: Villius Ren excusing women from watching violent scenes of his own making, and standing in front of the Decresian people whose lives he had destroyed, to offer them entertainment of the kind only a twisted few sought.

Oland always knew enough of The Craven Lodge’s plans to fulfil his role as servant, but never enough that he could not be surprised by new ones hatched in his absence. Without the slaughtered beasts, Oland no longer knew what Villius Ren would do for the final round.

Around the arena, The Craven Lodge began to light torches as lines of women and girls were guided roughly along their rows.

“Oland Born!” whispered Villius, leaning over the edge of the box, stretching a hooked, gloved finger towards him.

Oland turned and looked up at him. “Yes, master?”

“I thought perhaps you might clean up after our next event. I’ll be watching, of course, because it appears that working unsupervised is something of which you are incapable.”

Oland had no plans to reply, until Villius’ eyes continued to bore into him. “Yes, master,” he said.

“You don’t have much ambition, do you?” said Villius. “There is not much point to you. But you do have a moderate talent for cleaning up. At the very least, I can remind you of that.”

He stood up straight, and gripped the edge of the royal box.

“Gentlemen!” he roared. “It is time for a test of… Agility! Time for a champion to step forward! For a true leader, one who can be declared the champion of all champions, and forever be seen as the ultimate power in Envar, someone the Kingdom of Decresian can look to with pride!”

It was clear to everyone that Villius Ren was setting himself up to garner this impressive string of accolades, because he would never bestow such praise on another man. Whatever he had planned, he was confident that he would be victorious.

Oland looked around and realised how easy that would be – there appeared to be no remaining contenders. Not one man had made it through the earlier rounds.

“I promised you a spectacle,” roared Villius, “and a spectacle I will deliver!”

To Oland’s left, at the entrance to the dungeons, a chained panther slowly made his way into the arena, dragging two guards behind him. As he struggled wildly against them, a shaft of torchlight struck the protruding contours of his ribs. Without warning, a thickset man was thrown into the arena from the gates at the opposite side. He was clearly no athlete. He appeared to be a simple villager, a hairy, stocky man, with a huge belly and small wide feet that turned inward. He was holding a sword as if for the first time.

As he came closer, Oland was struck by a sickening recognition. It was the butcher, Malachy Graham.

“Tonight,” roared Villius, thrilled by the rippling fear before him, “our panther will confront his opponent, a gentleman you may recognise as one who is used to slaughtering animals. Shall we see the panther’s fine haunches on his market stall by morning?” He laughed, joined only by The Craven Lodge, then gestured for the animal’s release.

The guards struggled again with the panther’s chains, fighting to keep their balance. When he was finally set free, he stood, blinking in the fading light, casting a long shadow across the dusty earth. Then, snarling and grunting, his belly close to the ground, he moved, painfully slowly, towards his prey.

Malachy Graham trembled before him, smelling, as he always did, of blood.

Oland was possessed by something that he had no time to comprehend. Before he realised what he was doing, he had jumped up on to the barrier, and was roaring. The panther spun towards him, whipping up a cloud of dust. The crowd gasped. A man who was clutching his young son to his chest reached out with his other hand to pull Oland back. But Oland broke free and he jumped into the arena. The panther pounced, but, as he moved through the air, Oland rolled underneath him, and was quickly on his feet. He reached down for the butcher’s sword.

The panther pounced again, his jaws gaping. Oland vaulted into the air, wielding the sword above his head, swinging it swiftly downward, slicing through the animal’s flesh. The panther howled. Oland stared, horrified at the depth of the wound; he had almost halved him. The panther slumped to the ground where he writhed briefly, whimpered, then died.

Oland could not speak. The first sound he heard was that of the sword hitting the ground as it slid through his sweat-soaked palm. The second was the thanks that coughed out of the fallen butcher. The third sound – the loudest – came from the cheering crowd. But it was short-lived; they quickly fell silent as the dungeon gates were opened and two more panthers were released.

As if possessed, Oland picked up his sword in one hand and, with the other, grabbed Malachy Graham and dragged him to the barriers, where people rushed to haul him over to the other side.

Oland ran towards the centre of the arena, drawing the panthers away from the crowd. He turned and roared as he ran towards them, swiftly engaging them in a converging fight. The battle between them was a blur of sword and blood. First one fell, then the other. And, in minutes, it was over.

The three panthers lay dead in the arena and, beside them, stood Oland Born, rigid in the smoking torchlight. The crowd was as silent as six in the morning. Oland felt as if he were among them, a spectator watching a boy he did not know. Slowly, their cheers filled the night sky. Oland’s eyes were fixed on his own bare feet, mesmerised by the dark blood spattered across them. It led to a rich crimson pool that spread from beneath the animals. A violent image of a ferocious, towering beast flashed into Oland’s mind, and his chest started to heave.

Cries broke out across the arena and, when Oland looked up, a boy no older than him was being wrestled from the crowd by a guard. He had short, choppy black hair and fierce, dark eyes that were almost black. He fought hard, struggling against the guard’s bulging arm around his waist. Oland wondered what the boy had done. He watched as the guard carried him up to the last step. The boy struggled one last time. He raised his arm, tensed it, tightened his hand into a fist, then sent a sharp elbow backward into the stomach of the guard. The man’s face contorted and he dropped him. A smile broke out across the boy’s face and it was transformed. Oland’s eyes shot wide. He knew then why the boy was being kicked out. For he was not a boy at all. He was a girl. A very pretty girl, in fact. And then she was gone.

A loud bell tolled over the uproar, until the still-cheering crowd was quietened. Villius Ren gestured for Oland to approach the royal box. Oland didn’t move. Villius beckoned him again. Oland moved slowly towards him.

“People of Decresian,” roared Villius, “are we witnessing the historical first meeting of slavery and bravery?” He laughed loud.

The crowd was utterly silent as Oland walked up the steps to the royal box and stood beside Villius. Oland’s heart pounded. He looked out at the people of Decresian. He knew that they had been cheering not because he had taken lives, but because he had saved one.

A rumbling noise grew from the crowd.

Ignoring it, Villius laid his hands on Oland’s shoulders and turned him slowly towards him. He leaned down and whispered into his ear: “I will enjoy seeing if you can clean up the mess that will be the rest of your life.”

Oland thought about his mother and father, their goodness and badness, the terrible circumstances in which he was born: a night of violence and betrayal, of murder and flames and loss. Could any good come of a child born amid such devastation? Would misfortune forever shadow him?

A man’s voice echoed from across the arena: “Champion!”

Another voice joined it. “Oland Born! Champion!”

And another. “Champion! Champion!”

“Enough!” roared Villius, raising his head, his eyes wild. “Enough! Enough! Enough!”

He was still gripping Oland’s shoulders. His fingertips were white. As he pulled away, he locked eyes with his young servant.

In that moment, Oland could have sworn he saw, in the eyes of Villius Ren, a spark of fear.

Villius Ren was turned towards Wickham as Oland passed.

Wickham was speaking. “Yes, Villius,” he was saying, “for how long?”

“No more than a week,” said Villius. “I suppose you could call it a commission. I am anticipating the arrival of many dignitaries to Decresian. They will expect after-dinner tales that reflect a more… Envarly view. Settings that go beyond small tales of Decresian.”

Oland could see Wickham’s jaw clench and unclench rapidly.

“We must show these dignitaries that we understand their culture…” said Villius.

Wickham leaned to the side to allow Oland to fill his goblet. “Perhaps, Villius, as an alternative,” he said, “I could speak with the countless soldiers you have taken from all these dignitaries’ homelands… and have them enlighten the dark recesses of my tiny mind.”

Oland’s arm froze between Wickham’s shoulder and Viande’s on the other side. He had never heard Wickham so bold. He glanced at Villius Ren to see his reaction.

At first, Villius was silent. “You may leave immediately,” he said, after a moment. He stood up and walked away. This came as no surprise to Oland. Villius Ren delivered orders, never expecting them to be questioned, so he often left without registering a response. It was, in fact, Wickham’s reaction that surprised Oland: he was sitting motionless, with an expression of utter panic on his face.

As Oland moved on to Viande, Wickham jumped up and fled. Viande had pushed back his chair and positioned himself with one leg bent to the side, the other one straight out in front as if he were poised to trip someone up. He had been throwing Brussels sprouts into the air and catching them in his mouth, and he was now gnawing on a bone, drooling, snorting through his cavernous nostrils. He came to a piece of gristle and he growled, spitting it out with such force that it shot forward, striking Oland’s face, where it hung briefly from his jaw, then fell. Oland’s stomach turned. He rushed from the room, ignoring the familiar discord of The Craven Lodge’s laughter.

Oland scrubbed his face at the kitchen sink and, while he was there, took two plates of leftovers to eat in The Holdings – the second to keep for later that night. The Craven Lodge would not miss him for half an hour, and, certainly, he would not miss them. He took out his tinderbox and lit a small fire. He sat on a stool beside it with a plate on one knee and The Banon Servant open on the other. As he turned to the page where he had left off, something slipped from the play and fell to the floor. He glanced down. It was a teal-coloured envelope, sealed in gold wax stamped with the intricate royal D of Decresian. Teal and gold were the colours of King Micah’s reign. Oland set his plate and the play on the floor, wiped his hand on his napkin and picked up the envelope. He turned it over. He froze. There was a name written across it. And the name was Oland Born.

You live in the ruins of a once-proud kingdom destroyed by greed and misguided ambition. But fear not – Decresian shall be restored. And it falls to you, Oland Born, to do so. On such young shoulders, it will prove astonishing how light this burden will be.

Your quest is to find the Crest of Sabian before The Great Rains fall, lest the mind’s toil of a rightful king be washed away.

In life, a father’s folly may be his son’s reward.

In case this letter were to fall into the wrong hands, to guide you, know this:

Depth and height

From blue to white

What’s left behind

Is yours to find.

Be wise in your choice of companion and, by nightfall, be gone.

In fondness and faith,

King Micah of Decresian

The letter was dated the night King Micah died. Oland reread his name on the envelope. He reread it in the letter. He was utterly bewildered. How could King Micah have ever known the name of a boy who was born after his death? Oland read the king’s words several times more and, each time, new questions arose. Where was Sabian? Why was its crest important to Decresian? Why was he chosen to find it? Oland thought of the homeless man in the village, how only a crazy man believed that The Great Rains would return. A crazy man and a dead king. Whose ‘mind’s toil’ was King Micah speaking of? Who was the rightful king? King Micah and Queen Cossima had had no children; Oland knew that to be the absolute truth. What father, what son was King Micah talking about? Why was he to leave before nightfall? How could King Micah have even known what night he would discover the letter? How could Oland possibly just leave everything to go on a quest?