Полная версия

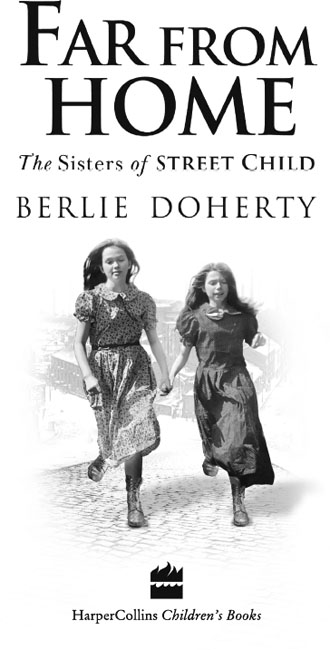

Far From Home: The sisters of Street Child

First published in Great Britain by HarperCollins Children’s Books in 2015

HarperCollins Children’s Books is a division of HarperCollinsPublishers Ltd,

1 London Bridge Street

London SE1 9GF

www.harpercollins.co.uk

Far From Home

Text copyright © Berlie Doherty, 2015

Cover design © HarperCollins Publishers 2015

Berlie Doherty asserts the moral right to be identified as the author of this work

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the non-exclusive, non-transferable right to access and read the text of this e-book on-screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, down-loaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins.

Source ISBN: 9780007578825

Ebook Edition © 2014 ISBN: 9780007578696

Version: 2014-11-19

Praise for Street Child, the companion novel to Far From Home:

‘A terrific adventure story, heart-warmingly poignant and a tribute to the resilience of the human spirit. A magnificent story.’

Daily Mail

‘Berlie Doherty has magic in her’

Junior Bookshelf

For Tommy, Hannah, Kasia, Anna-Merryn, Eda, Leo and Tess

CONTENTS

Cover

Title Page

Copyright

Praise

Dedication

Tell Me Your Story, Emily and Lizzie

1. Take Us With You, Ma

2. Safe Till Morning

3. The Two Dearies

4. Lame Betsy

5. Where You Go, I Go

6. Snatched in the Night

7. No Charity Children Here

8. Alone

9. Mrs Cleggins

10. We’re Going to a Mansion, Remember?

11. Bleakdale Mill

12. What Kind of Life?

13. A Pattern of Sundays

14. Winter

15. Miss Blackthorn

16. I Knew Your Ma

17. Cruel Crick

18. Sunshine

19. I Can Buy Our Freedom

20. Buxford Fair

21. Clog Dancing

22. Bess

23. The Lost Children

24. The Terrible Accident

25. No News for Emily

26. Where Am I?

27. Robin’s Plan

28. The Sheen

29. Revenge

30. I Can’t Remember

31. After the Fire

32. A letter from Dr Barnardo

33. Plans

34. One Last Thing

Acknowledgements

About the Author

By the same author

About the Publisher

We’re Emily and Lizzie Jarvis. We’re sitting by the window in our room. Outside, we can hear a soft kind of sighing, like the wind in the trees, though we know it isn’t that really. It’s a comforting sound, and it’s lulling us to sleep. But we can’t sleep yet. There’s so much to think about first, so much to talk about. So much remembering to do.

Would you like to know our story?

There used to be five of us in our family, and now there’s only two. After Pa died we had to move into a room in a big, crowded tenement house with Ma and our little brother, Jim, and we just managed to keep going because Ma got a job as cook in a Big House. But then she fell ill and she had to stop working. There was no money left to live on, no money for the rent. She gave her last coin to Jim and told him to buy a nice pie for us all, full of meat and gravy. He was so excited. He was too young to understand that Ma thought it was the last good meal we would ever have. But she couldn’t eat it, she was too ill.

And then the owner of the room came for the rent, and when he saw Ma’s empty purse, and her too sick to earn anything, he turned us out on the streets. Where was there to go? Ma took us to the Big House, down the steps to the kitchen, and she begged her friend Rosie to look after us. And then she told us we must stay there, without her. She must take Jim with her, and she must leave us behind. It broke her heart to tell us that, we knew. It breaks our hearts to think about it. But we must think about it. We must tell our story, every bit of it, so we never forget what it was like for us before we came here.

This is our story.

“Take us with you, Ma! Don’t leave us here!” Lizzie begged.

“I can’t,” her mother said. She didn’t turn round. “Bless you, I can’t. This is best for you. God bless you, both of you.”

Mrs Jarvis took Jim’s hand and bundled him quickly out of the door. It swung shut behind them with a loud thud.

Immediately Lizzie broke into howls of grief. “Ma! Ma! Don’t leave us behind!” she sobbed. “Don’t go without us!”

She tried to wrench open the door, but her sister put her arms round her, holding her tight. “It’s all right. It’s all right, Lizzie,” she whispered.

“We might never see them again!” Lizzie shook her away and covered her face with her hands. She didn’t want to see anything, didn’t want to hear anything.

“I know. It’s just as bad for me,” Emily said. “I didn’t want her to go. I didn’t want Jim to go.” Her voice was breaking up now; tiny rags of sound like brave little flags in the wind. “But Ma had no choice, did she? She wants to save us; that’s what she said. She brought us here so Rosie can take care of us.”

Rosie, their mother’s only friend in the world, came over to the two girls and drew them away from the door. “I’ll do my best,” she told them. She sat them down at the kitchen table where she had been making bread for the master of the house. She started smoothing flour away with the wedge of her hand, then tracing circles into it with her plump fingers. It was as if she was looking for words there to help her. All that could be heard were the shivering sobs that Lizzie made.

“Listen, girls,” Rosie said at last. “Your ma’s ill. You know that, don’t you? She ain’t going to get better.”

Lizzie stifled another sob. This time she let Emily creep her hand into her own, and squeezed and squeezed to keep the unimaginable pain of those words away.

“And you heard what Judd said? She’s the housekeeper, and what she says, goes. She’s the law round here, she is. She said she’d let you stay a bit, if you keep quiet and hidden, but not for ever. She can’t be feeding two grown girls on his lordship’s money, now, can she? She’d lose her job if he found out you were here, and so would I. I’ll do what I can for you, I promise, but I really don’t know what it is I can do. But at the very least I’ll save you from the streets, or even worse than that, from a life in the workhouse.” She shuddered, rubbing her stout upper arms vigorously as if the thought of the workhouse had chilled her bones. “Never, never. I’ll never let you go there, girls.”

She flapped her hands along her sleeves to try to dust away the flour.

“Busy, let’s be busy! Em’ly, you’ve got bread to make. See if it’s as good as your ma used to make. Lizzie, you’ve got a floor to sweep because I can’t touch flour without getting it everywhere I turn! And I’ve got a fire to mend. For pity’s sake, look at it! It’s crawling away like a rat down a hole.”

She lifted a pair of bellows from the side of the range and knelt in the hearth, working them into the dying embers to coax the flames back, then threw some knuckles of wood onto the glowing ashes. She sat back, watching the dance of the flames, and listened to the girls behind her. She could hear Emily standing up at last from the bench and starting to knead the dough on the table, popping the air out of it with a sure, firm touch, and at last settling into a rhythm, breathing with a slow kind of satisfaction as she did so. Rosie smiled to herself. She sounds just like her ma, she thought. And nothing ever calmed Annie Jarvis down as much as making bread. I’d enjoy working with Em’ly in the kitchen, if only Judd could find a way of letting her stay. Annie’s daughter, working alongside of me. What a pleasure that would be.

She lifted coals onto the fire, one by one, taking time over her task, not wanting to disturb the girls. At last, she heard Lizzie push the bench away and stand up; heard her gently sweeping the floor with the kitchen broom, scattering drops of water as she went so the dust didn’t fly. Rosie turned and saw that tears were still streaming down Lizzie’s face, burning her cheeks. “Ma, Ma,” she whispered as she worked. “I want you, Ma.”

As soon she had finished that task Rosie asked her to help with setting a tray to take upstairs, and with sorting out clean knives, forks and spoons to be locked away by Judd in the silver cabinet. The cutlery jittered in Lizzie’s hands, she was so scared of making a mistake, but at last the job was done and Rosie smiled her satisfaction.

“We get along very well in this job, don’t we, girls?” she said. “I think I can even sit down for a minute now.” She eased herself onto the bench, slipping her boots off, wriggling her toes.

There was the sudden pounding of feet down the stairs, the kitchen door was flung open, and there stood the housekeeper, lips pursed, grey eyes sharp and cold as points of ice. Rosie jumped to her feet, as though she’d sat on a cat.

“His lordship has come in early from his afternoon walk,” Judd announced. She jangled the keys that were hanging in a bunch from her belt. “I want you to get these girls out of my sight.”

“But he never comes down here, Judd,” Rosie said. “And the mistresses are away.”

“I said, out of my sight.” Judd took in the blazing fire, the clean floor, the dough rising plump as a chicken in the bread tins, and sniffed. “Now! I’ve never seen them in my life.” She turned her back, arms akimbo, so her elbows stuck out sharp and angled in her tight black sleeves.

Rosie took the girls by the hand and hustled them into the pantry. “He never comes down to the kitchen,” she muttered. “Judd’s behaving like a mother goose watching out for the fox. I’ll let you out when I can.”

She closed the pantry door quietly. The glow of the fire disappeared, and the sisters stood in complete darkness. Lizzie moved, and something thumped against her face. She stifled a shriek of shock, and nervously lifted up her hand to feel what it was, her other hand grasping Emily’s arm.

“Ducks!” she whispered, feeling a brace of the birds hanging above their heads. “Dead ducks!” and for some reason all the emotions of the day, the need to be quiet, the strangeness of everything, the knowledge that Emily was standing next to her breathing the same ducky air, and that Judd was watching out for his lordship, the fox; everything about the day welled up in her, until a pent-up explosion of sound burst out of her mouth.

“Are you crying?” Emily whispered.

“No,” Lizzie whispered back. Her voice was shaking. Her whole body was shaking. Tears of pain and laughter burnt her cheeks. “I am a bit. But I can’t stop giggling, Emily. Can’t stop.”

It seemed as if hours were passing while Emily and Lizzie stood in the dark pantry, listening to the to and fro of bustle in the kitchen: food being scraped off plates, pans being washed, the fire being raked. All this time they daren’t move, except to lower themselves away from the dangling ducks and squat down on the cold stone floor. Eventually the door opened a crack, the glow of a candle warmed the darkness, and Rosie’s face appeared.

“Me and Judd have finished down here,” she whispered. “I’ll put some cold meat out for you, and you must eat it before the mice do. There’s a water closet in the back yard for your necessaries, and a couple of rugs by the fire, so you can curl up there. Out you come.”

She helped them to stand and they stumbled out, stiff and cold, into the cosy firelight of the kitchen. Rosie rubbed their numb hands to warm them up. Her face was creased with concern. “His lordship’s eaten his supper, and he’s dozing in front of the fire like he always does when the ladies are away. He’ll totter off to bed any time now, so you’re quite safe till morning.”

“Is his lordship really a lord?” Lizzie asked.

“Heavens, no!” Rosie laughed. “We’d be in a much bigger house if he was, and there’d be servants all over the place. No, he’s a barrister or something like, and he can be as grumpy as I don’t know what if we get things wrong by mistake.” She led the girls over to the table and pushed the plates of meat and potatoes in front of them.

“He makes us feel like criminals sometimes because his coffee’s not hot enough or there’s too much salt in his potatoes. He hates it when the mistresses are away and there’s just him and the two Dearies. He can snap at you like a bear with a sore head sometimes.” She sat on the bench next to Lizzie and untied her house boots, letting her toes wriggle deliciously in the air. “Ooh, that’s better. Judd’s right, he’d put us out on the street, all of us, if he thought we was doing something behind his back, feeding waifs and strays.”

“We’re not waifs and strays!” Lizzie protested.

“We are now,” Emily reminded her. “Where’s home, now Mr Spink has kicked us out?”

Rosie undid the ties of her cap and loosened her long, dark hair. She patted Emily’s hand and stood up. “But he ate every bit of that bread you made, Em’ly, and then asked for more! That’s the first time since Annie left off working here. So we’ve high hopes for you. But then you might do me out of a job, and where would I be? You teach me, just like your ma taught you. It’ll take a bit of doing, so I’ll need you here a while!” She bent down to pick up her boots, and quickly kissed the tops of their heads. “Good night, girls. God bless.”

“I’m too tired to eat anything,” Lizzie said when Rosie had gone, locking the door behind her. “I just want to go to sleep, Emily.”

“You heard what Rosie said. Eat, before the mice get it. And suppose we get chucked out in the middle of the night? We’ll wish we had food in our bellies then, won’t we?”

Lizzie swallowed her cold meat dutifully, and Emily did the same. It was good meat, she could tell that, tender and tasty, but every mouthful seemed to clog up her throat and choke her. She cleared the plates away and then curled up next to Lizzie in front of the fire.

“You won’t stay here without me, Emily?” Lizzie murmured.

“Course I won’t. I’ll never leave you, Lizzie.” She stared into the pale flicker of the dying flames. “I wonder where Ma and Jim are now?” But Lizzie was already asleep. Images of Ma’s face swooned in and out of the darkness. It was as if, for a moment, she was still there with them, until the room grew into its night-time dark around her. “Please, God, let them both be safe,” Emily whispered. “Please let someone as kind as Rosie take care of them.”

A grey and drizzly dawn was seeping down through the basement window when Rosie shook the girls awake.

“I shall have to move you so’s I can get this fire lit,” she said. “Let’s hope that other nice loaf of yours was cooked proper before it went out, cos I forgot all about it in the excitement. That’s my trouble.”

“It’s all right, Rosie. I saw to it.” Emily yawned and opened the oven door to lift out the new loaf, freshly baked and barely cool. It smelled wonderful.

“Just how he likes it!” Rosie marvelled. “He’ll be a happy man this morning. He won’t be complaining that he’s breaking a tooth with every bite of my bread.”

Lizzie sat up and huddled the rug round her shoulders. She stared blankly round the strange kitchen, dazed by memories of yesterday: her mother, bent with pain and weakness; her brother, white-faced with shock and sorrow as he was bundled outside; the slam of the door; the sound of her own fists pummelling. Don’t leave us behind! Don’t go without us! Dimly she heard Rosie chattering away as if today was a day like any other.

“There’s a pump in the back yard to wash the sleep out of your faces,” she was saying. “And while you’re out there, you can pump up some water for me to boil for his breakfast tea, Em’ly. Lizzie, here’s a bowl of scraps; you can chuck these at the hens in the yard. I’ve got to fetch coal and get this fire going again. Then we can start the day proper.”

It was cold and damp in the yard, with a few sparks of snow in the air. Emily pumped up water to splash on her face, then nodded to Lizzie. Lizzie dipped her face down and then lifted up her head from the water; gasping with cold, her hair damp and clinging to her cheeks.

“Now you’ll feel a bit brighter,” Emily said. “And you like hens, so you’ve got a nice job to do next. And I reckon Jim would have liked my job, sprat though he is! He’d pretend he’s got muscles!” She paused, shocked with memory. I don’t know if we’ll ever see him again, she thought.

As if she had heard her, Lizzie burst out, “Why did Ma take him away with her, and leave us behind?”

“How could she leave him here? How could she expect Rosie to help all three of us?” Emily snapped. There came the tears again, sharp as needles behind her eyes. She smiled weakly at her sister. “Do your job, just do it. Let Rosie be pleased with us.”

The kitchen was warm again when they went back in. Rosie was trudging up from the cellar with a bucket of coal in each hand.

“I’m going up to light the house fires,” she told them. “Luckily, there’s only four to do today, as the mistresses are away.”

“What shall we do?” Emily asked.

“You could lay his tray for breakfast,” Rosie said. “He has tea, a boiled egg, bread and butter, and marmalade. I’ve put some aside for us, but we have it when he’s done. When you hear Judd coming down you’ll have to hide for ten minutes, while she has her breakfast. We have to pretend you’re not here, then she can say she knows nothing about you. Silly woman. I think she’ll relax a bit once his lordship leaves for work.”

Lizzie found the things that were needed for the tray. Emily put the kettle on the hob to boil, and sliced and buttered the bread neatly. When they heard footsteps on the stairs they scrambled into the pantry and waited, breathless, listening to Judd scraping porridge from the pan and slicing herself some bread. They heard Rosie return and Judd giving her orders for the day, and then their door was opened and they stumbled back into the light of the kitchen.

“Breakfast soon,” Rosie said. “I don’t know about you two, but I’m starving. It’s making the fires that does it, lugging ashes down the stairs and coals up. And when the mistresses are here there’s even more fires to do.”

“What are the mistresses like?” Lizzie asked.

“Well, his wife is as sour as a crabapple and his sister is like a crocodile! Heard of crocodiles? They’re all teeth and snap. That’s what she’s like. They’re away visiting relatives in the country, so things are a bit easy just now. But when they get back, I’ll be hustled off my feet. And then there’s the two Dearies.”

“And is there just you and Judd looking after everyone?”

“Lor, do you never stop asking questions?” Rosie gasped. “The Crabapple and the Crocodile have taken their own maids with them. They wouldn’t have me or Judd touching their clothes or their hair. Those maids are a hoity-toity pair, and I’m always glad to see them gone. And there’s a girl who comes in weekdays to help Judd with the beds and the dusting and polishing upstairs. Judd’s training her, but she’ll never be much good. She’s as lazy as a cat.”

“I could do her job!” Lizzie said, but Rosie shook her head. “She’s Judd’s niece,” she mouthed, glancing at the door. “That’s how it works in service. Someone speaks for you, and if you get the job, they have to train you and be responsible for you. I was lucky. Your mother spoke for me. She used to buy salmon and shrimps off me for his lordship’s supper, and we got to be pals. Like sisters. Oh.” She covered her face with her apron and emerged, red-eyed. “How was she to know I couldn’t make decent bread for the life o’ me!”

One of the bells over the kitchen door jangled sharply, making Lizzie jump.

“That’s it,” Rosie said. “Time for his lordship’s breakfast. Let me see. Bread’s done. Tea’s done. Tea cosy, marmalade, bread, butter, cup, saucer, spoon, milk, plate, knife. Sugar. Well done, Em’ly love. Tra-la! Open the door for me, Lizzie.” She sailed out of the kitchen and up the stairs with the tray, humming to herself.

Emily hugged her sister. “It’s all right here,” she said. “We’re fine for a bit, aren’t we?”

“Maybe Ma will be able to come back and fetch us, when she’s better,” Lizzie whispered. “That’s what I want.”

But Emily just shook her head, too upset to answer. She looked away, forcing back the sharp sting of tears before she could speak again. “Just try to be happy here, Lizzie. That’s what Ma wants for us. I like this big warm kitchen, and all the shiny pots and pans. I like being where Ma used to be when she was well, and doing the sorts of things she used to do, and cooking lovely food. I hope Rosie speaks for me. If I can’t be with Ma, and I know I can’t, I hope I can stay here.”

Lizzie turned away from her sister and slumped herself down on the bench. She knew Ma had loved this place too. Sometimes she used to bring bits of pie and bowls of stew home, when Judd allowed her to, and told the girls exactly how she had cooked them before she doled out their share. “What’s lovely, is cooking with good quality food,” she told them. “I can only afford scrag-ends and entrails for us usually, and coarse flour for bread. I do my best to make it taste good – but ooh, it’s another world, the way they live at the Big House. I want that for you, girls. Working in a fine big house!”

“I’d prefer to live in one!” Lizzie had said, and they had all laughed because the very idea was so crazy.

But here they were in the Big House, and Emily was doing her best to be as useful and as good a cook as Ma had been. Rosie wanted her to stay – that was clear. Lizzie bit her lip. What about me? she wanted to ask, but daren’t. What if Rosie spoke up for Emily and got her a job there? What if Emily could stay, and Lizzie couldn’t? What if Rosie couldn’t find another job for her? She hardly dared to let herself think about it. What would happen to her, wandering the streets all on her own? She’d rather go to the workhouse. She watched miserably as Emily busied herself tidying away pans, washing Judd’s breakfast plates, putting fresh water to boil. She seemed to know exactly what to do here, where things went, how to keep the kitchen neat and clean. She was even humming to herself as she worked. It’s true, Lizzie thought. She loves it here. Even though she’s crying inside like I am, she’s found out how to be a little bit happy.