Полная версия

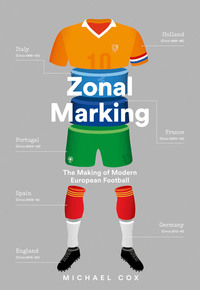

Zonal Marking

Upon his return to Ajax in 1993, Rijkaard was less mobile, more mature and happier playing defensively – so the position Van Gaal had earmarked for him was perfect. In Ajax’s 3–4–3, he played as the number 4, essentially anchoring the midfield ahead of captain Blind but dropping back to become a defender when necessary. But crucially, for a player who always wanted to be a playmaker, that’s precisely what Van Gaal demanded from him, and although asked to track opposition forwards, Rijkaard was also free to join the attack.

Rijkaard played a crucial role in Ajax’s 1995 European Cup Final win against Milan with his assist for Patrick Kluivert, but arguably more significant was the fact that he had taken control in the Ajax dressing room at half-time, laying into Clarence Seedorf and rallying his teammates, a moment Van Gaal would repeatedly cite as an example of a teammate stepping up and assuming responsibility. Rijkaard retired from football immediately after the triumphant final – which meant that his first departure from Ajax, in 1987, came after his manager Cruyff complained about his lack of leadership skills, and his second departure, in 1995, came after his manager Van Gaal was delighted with them.

Alongside Blind and Rijkaard was Frank de Boer, capable of playing left-back or left-sided centre-back, and therefore ideal for the flexible nature of Ajax’s defence. He was a wonderful distributor, particularly when spraying long, diagonal passes to a centre-forward who had drifted into the opposite channel. The classic example was the most famous Dutch pass of the 1990s, the pinpoint 60-yard diagonal to Dennis Bergkamp in the dying seconds of the 1998 World Cup quarter-final against Argentina. It was a good ball, made into a great one by Bergkamp’s extraordinary feat of bringing the ball down, beating Roberto Ayala and lifting the ball into the net with three quick touches. But Bergkamp’s favourite goal owed everything to his existing relationship with De Boer, as he explained when outlining how he received the pass. ‘You’ve had the eye contact … Frank knows exactly what he’s going to do. There’s contact, you’re watching him. He’s looking at you, you know his body language: he’s going to give the ball.’

Bergkamp knew, because De Boer had played that pass to him so often at club level, the best instance coming on Valentine’s Day 1993 at PSV. De Boer moved forward on the left of the Ajax defence and thumped a perfect curling ball into the right-hand channel for Bergkamp, who responded with a typical three-card trick: controlling the ball with his right thigh, then knocking the ball past the defender with his left foot, before chipping the ball over the goalkeeper with his right. Stripping away the context and looking purely at the technical skill involved, it was arguably more impressive than the Argentina strike. ‘It wasn’t a simple thing to do, but I’d done it so often with Dennis when we’d played together at Ajax,’ De Boer recalled when speaking of the Argentina goal. ‘When you watch the footage of Dennis at Ajax, I must have given him assists like that three or four times. We felt good together – when he went forward, I knew he wanted to go deep, and vice-versa … everything went right, and the pass was beautiful. But that was one of my strengths, and the chances of the pass getting there are higher for me than for other players.’ That’s because De Boer was simply an excellent passer, and that specific diagonal ball, from De Boer to the centre-forward, became a familiar part of Ajax’s attacking under Van Gaal.

Ajax’s final defender, right-sided Michael Reiziger, was a different type of footballer entirely: less creative but extremely quick, which meant he was the most effective defender at covering the space in behind, and lithe and tricky when bursting forward. Reiziger was another academy product, and when loaned out to Groningen was deployed as a right-winger, such were his attacking skills. ‘He’s quick, has good anticipation and sufficient ability to participate in build-up play,’ said Van Gaal, with ‘sufficient’ a telling choice of word. ‘Initially his defensive play was not so good, but this is an aspect which can be taught quickly – I give a player like him more time to play himself into the team. It’s not such a big gamble, we play near the halfway line, so Reiziger has time to use his basic speed to correct any mistakes.’

It’s crucial that Van Gaal suggested defending could be ‘taught quickly’, whereas Ajax’s passing patterns took longer to master. It was therefore much easier to convert an attacker into a defender than the other way round. In truth, Reiziger sometimes appeared to be Ajax’s weak link, but the importance of his speed shouldn’t be underestimated in combination with the guile of his defensive colleagues, and athleticism and adaptability meant that Van Gaal once declared him ‘the symbol of this Ajax side’. In all, this was the most technically gifted four-man defence football had witnessed. Significantly, three would later head to Barcelona: Reiziger in 1997, De Boer in 1999 and Rijkaard, as coach, in 2003.

But the Dutch defensive style had already been imposed at the Camp Nou by Cruyff in the early 1990s, and was naturally best epitomised by a Dutchman, the magnificent Ronald Koeman, who demonstrated a determination to attack like few other centre-backs in history. The most notable feature of his career – among eight league titles, two European Cups, the European Championship and 78 Dutch caps – is his extraordinary goalscoring tally at club level, 239 in all. He even finished joint-top goalscorer in the 1993/94 Champions League, with eight goals. Three were penalties, and Koeman also scored a number of free-kicks throughout his career – the 1992 European Cup Final winner against Sampdoria the most significant – but 239 remains a staggering figure for a player in his position. It’s 39 more than Kluivert and only 25 behind Bergkamp. Koeman is regarded as the most prolific central defender of all time.

‘I was a defender who wasn’t really a defender,’ Koeman explained. ‘I scored so many goals because I used to step forward out of defence a lot, and my coaches asked and expected me to do that. My set-pieces were a big strength too, but even in general play, I would be in those kind of positions, able to take long-range shots.’ His greatest mentor was clearly Cruyff, whom he’d played under at Ajax in 1985/86 and then, after a controversial switch to PSV, rejoined at Barcelona in 1989. His booming diagonal balls became a regular feature of Barca’s play, particularly when switching the ball out to left-winger Hristo Stoichkov, and Cruyff had a very special trust in Koeman, perhaps only rivalled by his affection for Pep Guardiola. ‘Koeman likes the football that I preach about,’ said Cruyff. ‘He’s the ideal man at the back, a defender who is good for 15 goals a season. He can live in that position because I want players like him, who can make decisive moves in tiny spaces.’

‘Koeman was one of the first central defenders with the quality not just to defend,’ said Guardiola, who Koeman took under his wing at Barca. ‘I think Johan Cruyff bought Ronald Koeman to show us, to teach us, why we need a central defender like Ronald … most of the quality was his build-up, amazing long balls, forty metres, quick balls. He is one of the best central defenders I’ve ever seen in my life.’ Koeman’s regular forward charges rarely exposed Barcelona in a defensive sense because they could rely on Guardiola’s selfless, intelligent play in the holding midfield position. This was particularly crucial when Cruyff played the 3–4–3, with Koeman the centre-back and Guardiola the holding midfielder. Guardiola, often wearing number 3 at this stage, would effectively become Barcelona’s main defender, covering for his attack-minded teammate in the original manner of Total Football.

While Guardiola is widely considered a deep midfielder, Cruyff often referred to him as a defender. ‘As a player he was tactically perfect but he said he couldn’t defend,’ said Cruyff. ‘I said: “I agree – in a limited way. You’re a bad defender if you have to cover this whole area. But if you have to defend this one small area, then you’re the best. Make sure that there are people to cover the other areas. As long as you do that, you can be a very good defender.” And he did become very good.’ Cruyff sometimes deployed Guardiola as a conventional centre-back; in late 1991 Cruyff even handed him the job of man-marking Real Madrid’s outstanding striker Emilio Butragueño, the reigning Pichichi. Perhaps the most significant example came in a 2–2 UEFA Cup draw away at Bayern Munich in April 1996; the idea of Guardiola, a midfielder, being deployed in defence would prove particularly prescient considering his own use of Javier Mascherano and Javi Martínez when later coaching these two clubs.

Cruyff insisted that Koeman and Guardiola, two players he praised primarily for their passing, were a perfectly functional pairing because of their positional strength and intelligence. ‘As the central defensive duo, they weren’t fast and they weren’t defenders,’ Cruyff admitted. But he believed there were only three passes that Barca needed to worry about: balls over the top would be intercepted by his goalkeeper, the aggressive Busquets; crossfield balls would be dealt with by his speedy full-backs Albert Ferrer and Sergi Barjuán, academy products and converted wingers; balls down the centre, meanwhile, wouldn’t be a problem because Cruyff was confident Koeman and Guardiola communicated well, and were flawless in a positional sense. Sometimes he referred to the duo as both ‘midfielder-defenders’, which summarised the Dutch interpretation of defenders – they aren’t really defenders at all.

Transition: Netherlands–Italy

Juventus required a penalty shoot-out to confirm their triumph over Ajax in the 1996 Champions League Final, but this nevertheless felt like a turning point in European football, the moment when Dutch dominance gave way to Italian ascendency. Ajax, the previous season’s Champions League winners, found themselves unable to cope with the speed and power of Juve’s forwards, and the Italian side should have killed the game before half-time.

For Ajax, the problem wasn’t simply defeat and the failure to retain their trophy, but the knowledge it was the end of an era. Midway through 1995/96 European football had been shaken by the Bosman ruling, which had two major impacts. First, players could run down their contracts and transfer elsewhere for free. Second, the three-foreigner rule was now illegal, and European clubs could field as many EU nationals as they liked.

No club suffered as much as Ajax. At the end of 1995/96 Edgar Davids, arguably Europe’s most coveted midfielder, left for AC Milan on a free transfer – previously, Ajax would have received a fee and reinvested the proceeds. Meanwhile, the liberalisation of the rules regarding the number of foreign players permitted meant there was now extra overseas demand for Ajax’s other stars, and within three years they found almost their entire Champions League-winning side had departed. Davids, Winston Bogarde, Edwin van der Sar, Michael Reiziger, Nwankwo Kanu and Patrick Kluivert all headed to Serie A, mirroring the shift in power. Bosman had made players, and Europe’s major leagues, considerably more powerful, and Ajax were no longer among Europe’s elite.

1996 also saw Ajax depart their much-loved De Meer Stadion, moving to the Amsterdam Arena – later renamed the Johan Cruyff Arena – in the south of the city. They encountered serious problems with the new stadium, which wasn’t simply a football ground, but a multipurpose arena also used for concerts. Grass didn’t grow properly, which hampered Ajax’s passing football, and to many supporters it just didn’t feel like home. Louis van Gaal initially intended to leave in 1996, but stuck around one more year for personal reasons. Cruyff, meanwhile, left Barcelona in 1996 and would never coach again, while Holland were hugely disappointing at Euro 96, thrashed 4–1 in the group stage by England, and exiting after a quarter-final penalty shoot-out defeat to France. Holland’s customary tournament arguments seemed particularly serious, too, with various suggestions of a divide between black and white players.

With Dutch football’s reputation taking a battering, then, Italy became the centre of European football. Serie A had been Europe’s strongest league throughout the 1990s, evidenced by their clubs’ dominance of the European competitions, but only now, with the sexier, more forward-thinking Ajax out of the picture, was its superiority unquestionable.

Whereas Ajax focused on youth development, Italian clubs depended on financial clout. The country’s major clubs were owned by absurdly wealthy businessmen – at least in theory, as many later found themselves financially ruined – who competed to sign the world’s greatest talents. The so-called ‘seven sisters’ of Italian football had emerged: Juventus, Milan, Inter, Roma, Lazio, Parma and Fiorentina all boasted world-class players, and all seven started each season with a genuine chance of glory. In terms of overall strength and competitiveness, there has probably never been a better league than Serie A during the mid- to late-1990s.

Stylistically, Serie A was in a peculiar place. Italian football had always been considered defensive, with its infamous catenaccio of the 1960s still influencing tactical thought. While the attack-minded Milan boss Arrigo Sacchi had revolutionised football in the late 1980s by overhauling catenaccio and introducing the pressing game, he’d been inspired by Ajax’s Total Football, and his approach was atypical for an Italian coach.

During this period Italian football’s major tactical themes were essentially debates between coaches who were pro-Sacchi and those who were Italian traditionalists. Sacchi promoted a proactive style of football in an inflexible 4–4–2 system, which featured no trequartista (the number 10) or libero (the sweeper). But, by nature, Italian coaches adapted their system to the opposition’s approach, most loved their trequartisti and many still insisted on a libero. Italian football during this era was not about following Sacchi’s Dutch-centric ideals, but about returning Serie A to the old Italian way.

4

Flexibility

In the closing stages of Juventus’s 1996 Champions League Final victory over Ajax, there was an unusual incident that summed up so much about Juventus, and so much about Italian football.

Ajax, in keeping with their customary approach, constantly switched play in the first half between right-winger Finidi George and left-winger Kiki Musampa. Juve’s aggressive 4–3–3 system, featuring three outright forwards in Alessandro Del Piero, Gianluca Vialli and Fabrizio Ravanelli, meant that neither of Juventus’s most impressive performers on the night, the unheralded full-back pairing of Gianluca Pessotto and Moreno Torricelli, were afforded protection against Ajax’s wingers, but both defenders were magnificent, sticking tight and refusing to let the Ajax wingers turn. Pessotto completely nullified Finidi, while Torricelli intercepted passes and launched quick counter-attacks. Louis van Gaal evidently decided that Ajax weren’t likely to get the better of Torricelli, and at half-time he removed Musampa. Ronald de Boer, who had started in central midfield, moved to the left.

Late in the game, however, Torricelli started to struggle with cramp, so for extra-time Van Gaal introduced Nordin Wooter, another speedy winger, to attack Torricelli, testing the right-back’s mobility. Juventus boss Marcello Lippi had already used his three substitutes, and therefore devised a novel solution: he switched his full-backs. Pessotto had played 90 minutes at left-back, but played extra-time at right-back, and stopped Wooter. Torricelli made the reverse switch, and was less troubled by the fatigued Finidi.

It was, on paper, a simple solution, but it’s difficult to imagine other full-back pairings of this era doing likewise. You wouldn’t have witnessed Brazil switching Cafu and Roberto Carlos, or Barcelona moving Albert Ferrer to the left and Sergi Barjuán to the right; it would have been unthinkable and fundamentally compromised their natural game. Italian sides, though, weren’t about playing their natural game; they were about stopping opponents from playing theirs. They were – and still are – defensive-minded, reactive and tactically intelligent. Torricelli and Pessotto weren’t playing out of position, they were in another position they could play.

For all Juventus’s superstars during the mid- to late-1990s, it’s those underrated, jack-of-all-trades, versatile squad players who best exemplify the nature of Italian football. Lippi could depend on four players who would struggle to identify their best position, something that would be considered a sign of weakness elsewhere but was very much a virtue in Serie A. Torricelli, Pessotto, Angelo Di Livio and Alessandro Birindelli could play as full-back, wing-back or wide midfielder, they could play on the left or the right and sometimes through the centre. These were the club’s leaders. ‘Every year we sold our best players, but the backbone of the squad stayed,’ remembered Lippi. ‘And when new players would arrive and wouldn’t work as hard, players like Di Livio or Torricelli would put an arm around them and say, “Here, we never stop, come on!,” and the message would come from these players who had won the league and the Champions League, and on the pitch they worked their arses off. They were exceptional examples.’

This quartet of players were workers rather than geniuses, with a single year of Serie A experience between them upon their arrival at Juventus. Torricelli was plucked straight from amateur football at a cost of just £20,000; Pessotto had played five of his six full campaigns in the lower leagues; Di Livio had played eight seasons without any Serie A experience; and Birindelli had played more in Serie C than Serie B, never mind in Serie A. ‘It’s not just the real quality players like Zinedine Zidane or Del Piero that captured everyone’s attention,’ observed Roy Keane, whose Manchester United side regularly faced Juventus in the Champions League during this era. ‘But tough, wily defenders, guys nobody’s ever heard of, who closed space down, timed their tackles to perfection, were instinctively in the right cover positions and read the game superbly.’

That described Torricelli, Pessotto and Birindelli perfectly; they were probably defenders who could play in midfield, while Di Livio was the reverse. He was nicknamed Il soldatino by Roberto Baggio, who observed that he continually sprinted up and down the touchline like a little soldier. It didn’t matter which touchline, and while Di Livio was right-footed, he occasionally took corners with his left. Usually the mark of a technically outstanding player, the workmanlike Di Livio hardly falls into that category. In his case, it was a sign of a flexible player who had worked hard to improve his weaknesses and could adapt to any situation.

The rest of Juventus’s backbone were similarly versatile. Ciro Ferrara and Mark Iuliano were centre-backs, but when Juventus defeated Ajax again the following season, this time in the semi-finals, both were deployed in the full-back positions and performed excellently, while Alessio Tacchinardi, usually a holding midfielder, filled in at centre-back. Meanwhile, Antonio Conte was the epitome of the Italian midfielder: a dependable general capable of performing equally well in the centre or out wide. These players could seemingly be deployed anywhere within the defensive section of the side, which allowed their manager, Lippi, to become Europe’s most revered tactician, changing formations regularly, between games and within games. ‘If you have smart players who understand tactics and are comfortable in big systems, then making frequent changes can be a big plus,’ Lippi believed. So did his compatriots.

Lippi was the most celebrated graduate from Coverciano, the Italian Football Federation’s technical headquarters. Based in Florence, just over a mile east of Fiorentina’s Stadio Artemio Franchi, Coverciano was different from Clairefontaine in France, for example, which was famous for its development of players. Instead, Coverciano focused primarily on the development of coaches, and was effectively football’s version of Oxford – Europe’s greatest university of football coaching.

Coverciano’s highest coaching certificate was necessary to coach in Serie A, but entry requirements were strict, with only 20 places per year. You needed to be an Italian citizen or to have resided in the country for two years, you needed to have qualified from the second level of coaching course, and then you had to complete an assessment based upon your playing career (35 points), coaching career (40 points) and academic career (5 points), with 20 points on offer for your performance in an interview.

Playing and coaching careers were assessed according to an absurdly complicated points system that awarded 0.02, 0.04 and 0.06 points for club appearances in Serie C, B and A respectively, with bonus points available for winning Serie A, playing internationally or appearing in the World Cup. The famous quote from Arrigo Sacchi, who never played football professionally, about how ‘a jockey doesn’t need to have been a horse’, becomes more significant when you realise the extent to which the Italian coaching school was predisposed to favour former players.

In all, graduating from Coverciano involved over 550 hours of study, and because it is mandatory for coaching in Serie A, Italian coaches were furious when Sampdoria circumvented the rules and appointed the underqualified David Platt, although technically he was only an assistant because he lacked the requisite certificates. ‘It’s like a student nurse conducting a heart operation,’ blasted Bari manager Eugenio Fascetti. There was widespread glee when Platt departed after an unsuccessful two-month tenure. Luciano Spalletti unexpectedly found himself as a manager in Serie A without the necessary qualifications after back-to-back promotions with Empoli and, after publicly questioning whether he was good enough for the top flight, juggled coaching with studying, regularly making the trip across Tuscany to Coverciano. The academic approach has proved invaluable to numerous Italian coaches. With modules on ‘Football technique’, ‘Training theory’, ‘Medicine’, ‘Communication’, ‘Psychology’ and ‘Data’, they are thoroughly prepared for the rigours of Serie A. Before graduation, students are obliged to write a dissertation. Carlo Ancelotti wrote about ‘Attacking Movements in the 4–4–2 Formation’, Alberto Zaccheroni’s was concisely titled ‘The Zone’ and Alberto Malesani offered ‘General Considerations from Euro 96’. These documents are stored in Coverciano’s library, which boasts 5,000 such papers.

Lippi is among the greatest advocates of Coverciano. ‘I started to understand why, as players, you were asked to do certain things,’ he explained in Vialli’s book The Italian Job. ‘It was an eye-opener because it encouraged me to question and evaluate everything we take for granted in football. That’s what I truly found important about Coverciano, the exchange of ideas between myself and my colleagues. The more I think about it, what I hold dear is not just the course in itself, it’s the atmosphere around it, that challenging, thought-provoking environment … Coverciano does not give you truths, it gives you possibilities.’

That sense of openness was echoed by Gianni Leali, head of Coverciano during the mid-1990s. ‘We don’t teach one system,’ he said. ‘We teach them all, and then show the advantages and disadvantages of each one. There’s a variety here, and that makes Serie A a lot more interesting.’ Whereas Dutch football was fixated on 4–3–3 or 3–4–3, Italian football featured almost every possible formation, and just as Juventus’s versatile defensive players had no defined position, Lippi and other Italian coaches had no defined system. They reacted to the opposition’s tactics to a greater extent than coaches elsewhere, and they routinely substituted star forwards to introduce defensive reinforcements.