Полная версия

The Weirdstone of Brisingamen and The Moon of Gomrath

“Ah! But there goes he who can tell us more about the stone.”

He pointed to a speck floating high over the plain, and whistled shrilly.

“Hi, Windhover! To me!”

The speck paused, then came swooping through the air like a black falling star, growing larger every second, and, with a hollow beating of wings, landed on Fenodyree’s outstretched arm – a magnificent kestrel, fierce and proud, whose bright eyes glared at the children.

“Strange company for dwarfs, I know,” said Fenodyree, “but they have been prey of the morthbrood, and so are older than their years.

“It is of Grimnir that we want news. He went by here: did he seek the lake?”

The kestrel switched his gaze to Fenodyree, and gave a series of sharp cries, which obviously meant more to the dwarf that they did to the children.

“Ay, it is as I thought,” he said when the bird fell silent. “A mist crossed the plain a while since, as fast as a horse can gallop, and sank into Llyn-dhu.

“Ah well, so be it. Now I must away back to Cadellin, for we shall have much to talk over and plans to make. Farewell now, my friends. Yonder is the road: take it. Remember us, though Cadellin forbade you, and wish us well.”

“Goodbye.”

Colin and Susan were too full to say more; it was an effort to speak, for their throats were tight and dry with anguish. They knew that Cadellin and Fenodyree were not being deliberately unkind in their anxiety to be rid of them, but the feeling of responsibility for what had happened was as much as they could bear.

So it was with heavy hearts that the children turned to the road: nor did they speak or look back until they had reached it. Fenodyree, standing on the seat, legs braced apart, with Windhover at his wrist, was outlined against the sky. His voice came to them through the still air.

“Farewell, my friends!”

They waved to him in return, but could find no words.

He stood there a moment longer before he jumped down and vanished along the path to Fundindelve. And it was as though a veil had been drawn across the children’s eyes.

CHAPTER 8

MIST OVER LLYN-DHU

Autumn came, and in September Colin and Susan started school. Work on the farm kept them busy outside school hours, and it was not often they visited the Edge. Sometimes at the weekend they could go there, but then the woods were peopled with townsfolk who, shouting and crashing through the undergrowth, and littering the ground with food wrappings and empty bottles, completely destroyed the atmosphere of the place. Once, indeed, Colin and Susan came upon a family sprawled in front of the iron gates. Father, his back propped against the rock itself, strained, redder than his braces, to lift his voice above the blare of a portable radio to summon his children to tea. They were playing at soldiers in the Devil’s Grave.

Nothing remained. This place, where beauty and terror had been as opposite sides of the same coin, was now a playground of noise. Its spirit was dead – or hidden. There was nothing to show that svart or wizard had ever existed: nothing, except a barn full of owls at Highmost Redmanhey, and an empty wrist where once a bracelet had been.

The loss of the bracelet was the cause of slight friction between the Mossocks and the children. Bess was the first to notice that the stone had gone, and Susan, not knowing what to do for the best, poured out the whole story. It was really too much for anyone to digest at once, and Bess could not think what to make of it at all. She was upset over the loss of the Bridestone, naturally, but what troubled her more was the fact that Susan should be so fearful of the consequences that she would invent such a desperate pack of nonsense to explain it all away. Gowther, on the other hand, was by no means so certain that it was all fantasy. He kept his thoughts to himself, but in places the story touched on his recent experiences far too accurately for comfort. However, the affair blew over and no one mentioned it again, though that does not mean to say it was forgotten.

Shortly before Christmas Colin discovered that the owls had left the barn, and for days after, the children were in a fretful state of anxiety over what the disappearance could mean.

“Either Cadellin’s got the stone back again,” said Colin, “or he’s lost the fight.”

“Or perhaps it’s only that he’s sure we’re out of danger, or perhaps … no, that wouldn’t make sense … oh, I wish we knew!”

And although they spent two whole days ranging the woods from end to end, they found no clue to help them. If there had been a struggle as fierce as Cadellin had predicted, then it had left no trace that they could see.

It was a young winter of cloudless skies. The stars flashed silver in the velvet, frozen nights, and all the short day long the sun betrayed the earth into thinking it was spring. And late one Sunday afternoon at the end of the first week in January, Colin and Susan climbed out of Alderley village, pushing their bicycles before them. They walked slowly, for it was not a hill to be rushed, and the last stretch was the worst – straight and steep, without any respite. But once they were at the top, the going was comparatively good.

They did not ride more than a hundred yards, however, for Colin, who was leading, jammed on his brakes so violently that he half fell from his bicycle and Susan nearly piled on top of him.

“Look!” he gasped. “Look over there!”

It could be only Cadellin. He stood against the skyline of Castle Rock, staff in hand, facing the plain.

At once all promises were forgotten: the children dropped their bicycles and ran.

“Cadellin! Cadellin!”

The wizard spun round at the sound of their voices, and made as if to leave the rock. But after three strides he checked his pace, stood for a moment, and then walked to the bench and sat down.

“Oh, Cadellin, we thought something must have happened to you!” cried Susan, sobbing with relief.

“Many things have happened to me, but I do not feel the worse for that!”

There was displeasure in his face, tempered with understanding.

“But we were so worried,” said Colin. “When the owls disappeared we wondered if you’d … you’d …”

“I see!” said Cadellin, breaking into laughter. “No, no, no, you must not look on life so fearfully. We called the birds away because we knew that you were no longer in danger from the morthbrood.”

“Well, we thought of that,” said Colin, “but we couldn’t help thinking of other things, too.”

“But what about the morthbrood?” said Susan. “Have they still got my Tear?”

“Yes, and no,” said the wizard. “And in their greed and deceit lies all our present hope.

“Grimnir has the stone. He should have delivered it to Nastrond, but the morthbrood and he intend to master it alone. Perhaps they believe Firefrost holds power for them. If so, they are mistaken!

“And here we have wheels within wheels; for Grimnir and Shape-shifter, as rumour has it, are planning to reap all benefits for themselves, and to leave the brood and the svarts to whistle for their measure. So says rumour; and I can guess more. I know Grimnir too well to imagine that he would willingly share power with anyone, and the Morrigan, for all her guile, is no match for him. And it may be among all this treachery that we shall find our chance; but for the present we watch, and wait. Firefrost is not in Nastrond’s hand, and for that we must be thankful.

“There! You have it all, and now we go our ways once more.”

Colin and Susan were so relieved to find the wizard unharmed that parting from him did not seem anything like so bleak an experience as it had been before.

“Is there still nothing we can do?” asked Susan.

“No more than you have been doing all these months. You have played your part well (if we forget this afternoon!), and you must continue to do so, for we do not want you to fall foul of that one again.”

He pointed with his staff. About the trees through which the Black Lake could normally be seen hung a blanket of fog. Elsewhere, as far as the eye could see, the sunset plain was free of haze or mist, but Llyn-dhu brooded under a fallen cloud.

“It has been there for over a week,” said the wizard. “I do not know what he is about, but my guess is that he is trying to seal Firefrost within a circle of magic to prevent its power from reaching Fundindelve. He will not succeed, and he has not the strength to destroy the stone. But then, I have not the power to take it by force, so the matter rests, though we do not.”

Cadellin walked with the children as far as the road, and they left him, lighter at heart than they had been for many a day.

The mist was still there the following morning. Colin and Susan had set out on their bicycles soon after dawn to spend the day exploring the countryside, and when they had reached the top of the “front” hill Colin had suggested taking another look at Llyn-dhu. So there they now were, sitting on Castle Rock, and gazing at the mist.

For a long time they were silent, and when next Colin spoke he did no more than put his sister’s thoughts into words.

“I wonder,” he said, “what it’s like … close to.”

“Do you think we’d be breaking a promise if we went just to look?”

“Well, we’re looking now, and we’d be doing the same thing, only from a lot nearer, wouldn’t we?”

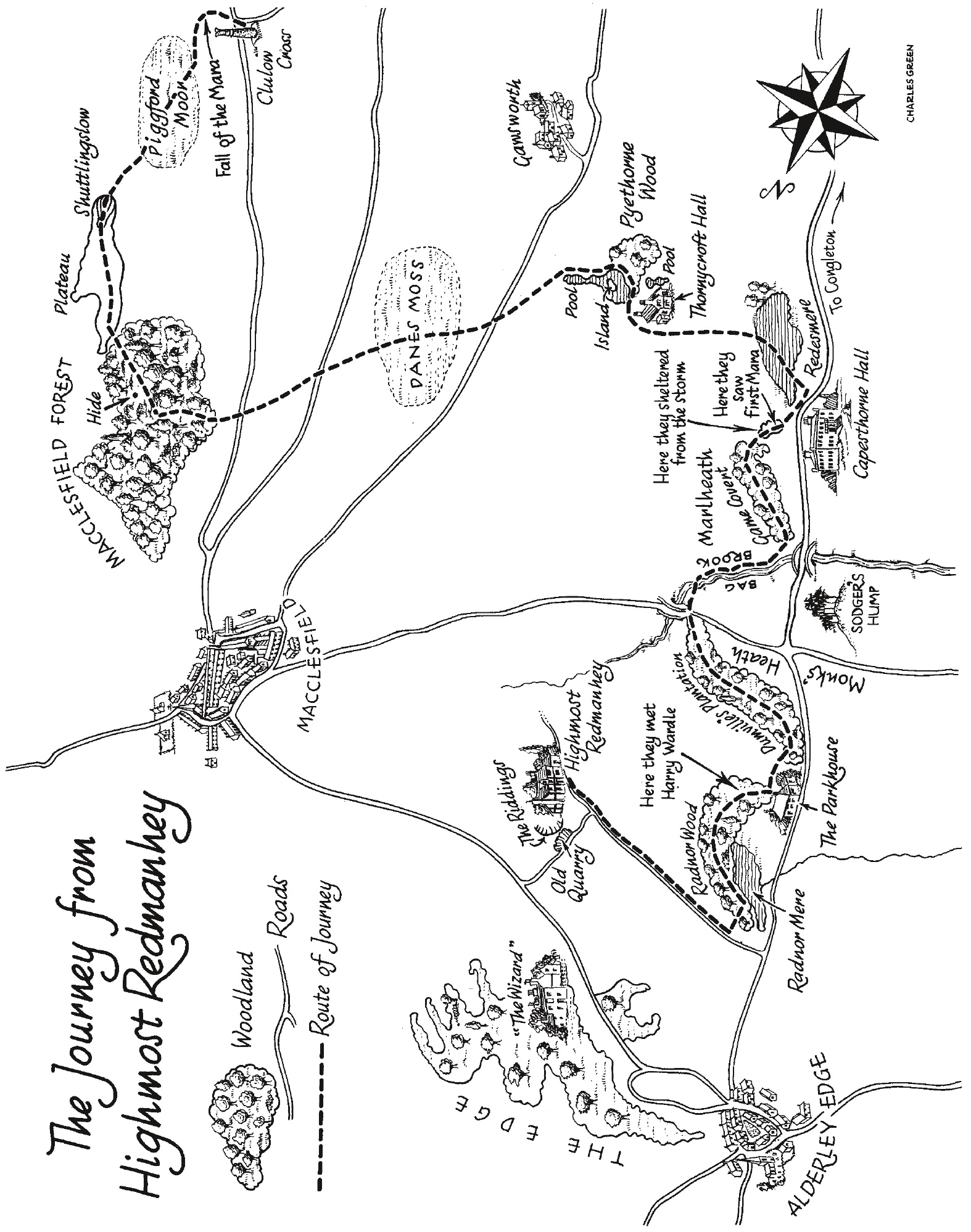

That decided it; but then they realised that they had not the least idea of how to reach the lake. However, by picking out what few landmarks they knew, it seemed that if they made for Wilmslow, and there turned left, they would be heading in something like the right direction. So, without further delay, Colin and Susan rode to Alderley, bought a bottle of lemonade to go with their sandwiches, posted a view of Stormy Point to their father and mother, and within thirty minutes of making their decision were in the centre of Wilmslow, and wondering which road to take next.

“There’s the man to ask,” said Colin.

He had seen a small beetle of a car, from which was emerging a police sergeant of such vast proportions that he hid the car almost completely from view. It was incredible that he could ever have fitted into it, even curled up.

The children cycled over to him, and Colin said:

“Excuse me, can you tell us the way to Llyn-dhu, please?”

“Where?” said the sergeant in obvious surprise.

“Llyn-dhu, the Black Lake. It’s not far from here.”

The sergeant grinned.

“You’re not pulling my leg, are you?”

“No,” said Susan, “we’re not – promise!”

“Then somebody must be pulling yours, because there’s no such place of that name round here that I know of, and I’ve been at Wilmslow all of nine years. Sounds more Welsh than anything.”

Colin and Susan were so taken aback that, for a moment, they could not speak.

“But we saw it from Castle Rock less than an hour ago!” said Susan, and tears of exasperation pricked her eyes. “Well, we didn’t really see it, because it was covered in mist, but we know it’s there.”

“Mist, did you say? Ah, now perhaps we’re getting somewhere. There’s been fog on Lindow Common for days, and the only lake in the district is there. Do you think that’s what you want?”

Llyn-dhu, Lindow: it could be: it had to be!

“Ye-es; yes, that’s it,” said Colin. “We must have got the name wrong. Is it far?”

They followed the sergeant’s directions, and after a mile came upon an expanse of damp ground, covered with scrub, and heather, and puddles. A little way off the road was a notice board which stated that this was Lindow Common, and that cycling was prohibited. And in the middle of the common was a long lake of black, peat-stained water.

The children stood on the slimy shore. The air was dank, and the scenery depressing. The common was encircled by a broken rash of houses, such as may be seen, like a ring of pink scum, on the outskirts of most of our towns and villages today.

“Garlanded with mosses and mean dwellings.” Fenodyree’s words came back to the children as they looked at the brick-pocked landscape. But what was most obviously wrong was that they could see all this. For if they were indeed at Llyn-dhu, then, within the space of an hour, it had rid itself of every trace of the mist that had shrouded it for the last ten days.

“Do you think this is it?” said Colin.

“Ugh, yes! There couldn’t be two like this, and it’s a black lake all right! I wonder what’s happened.”

“Oh, let’s go,” said Colin, “this place gives me the willies. We’ve done what we set out to do; now let’s enjoy the rest of the day.

After a cup of coffee in Wilmslow to dispel the Lindow gloom, the children pedalled back towards Alderley. They had no plans, but the sun was warm, and there were a good six hours of daylight left to them.

They were crossing the station bridge at Alderley when they saw it. A light breeze, blowing from the north-east, trailed the village smoke slowly along the sky, but halfway up the nearer slope of the Edge a ball of mist hung as though moored to the trees. And out of the mist rose the chimneys and gaunt gables of St Mary’s Clyffe, the home of Selina Place.

CHAPTER 9

ST MARY’S CLYFFE

The room was long, with a high ceiling, painted black. Round the walls and about the windows were draped black velvet tapestries. The bare wooden floor was stained a deep red. There was a table on which lay a rod, forked at the end, and a silver plate containing a mound of red powder. On one side of the table was a reading-stand, which supported an old vellum book of great size, and on the other stood a brazier of glowing coals. There was no other furniture of any kind.

Grimnir looked on with much bad grace as Shape-shifter moved through the ritual of preparation. He did not like witch-magic: it relied too much on clumsy nature spirits and the slow brewing of hate. He preferred the lightning stroke of fear and the dark powers of the mind.

But certainly this crude magic had weight. It piled force on force, like a mounting wave, and overwhelmed its prey with the slow violence of an avalanche. If only it were a quick magic! There could be very little time left now before Nastrond acted on his rising suspicions, and then … Grimnir’s heart quailed at the thought. Oh, let him but bend this stone’s power to his will, and Nastrond should see a true Spirit of Darkness arise; one to whom Ragnarok, and all it contained, would be no more than a ditch of noisome creatures to be bestridden and ignored. But how to master the stone? It had parried all his rapier thrusts, and, at one moment, had come near to destroying him. The sole chance now lay in this morthwoman’s witchcraft, and she must be watched; it would not do for the stone to become her slave. She trusted him no more than could be expected, but the problem of how to rid himself of her when she had played out her part in his schemes was not of immediate importance. The shadow of Nastrond was growing large in his mind, and in swift success alone could he hope to endure.

With black sand, which she poured from a leather bottle, Shape-shifter traced an intricately patterned circle on the floor. Often she would halt, make a sign in the air with her hand, mutter to herself, curtsy, and resume her pouring. She was dressed in a black robe, tied round with scarlet cord, and on her feet were pointed shoes.

So intent on her work was the Morrigan, and so wrapped in his thoughts was Grimnir, that neither of them saw the two pairs of eyes that inched round the side of the window.

The circle was complete. Shape-shifter went to the table and picked up the rod.

“It is not the hour proper for summoning the aid we need,” she said, “but if what you have heard contains even a grain of the truth, then we see that we must act at once, though we could have wished for a more discreet approach on your part.” She indicated the grey cloud that pressed against the glass, now empty of watching eyes. “You may well attract unwanted attention.”

At that moment, as if in answer to her fears, a distant clamour arise on the far side of the house. It was the eerie baying of hounds.

“Ah, you see! They are restless: there is something on the wind. Perhaps it would be wise to let them seek it out; they will soon let us know if it is aught beyond their powers – as well it may be! For if we do not have Ragnarok and Fundindelve upon our heads before the day is out, it will be no thanks to you.”

She stumped round the corner of the house to the outbuilding from which the noise came. Selina Place was uneasy, and out of temper. For all his art, what a fool Grimnir could be! And what risks he took! Who, in their senses, would come so obviously on such an errand? Like his magic, he was no match for the weirdstone of Brisingamen. She smiled; yes, it would take the old sorcery to tame that one, and he knew it, for all his fussing in Llyn-dhu. “All right, all right! We’re coming! Don’t tear the door down!”

Behind her, two shadows moved out of the mist, slid along the wall, and through the open door.

“Which way now?” whispered Susan.

They were standing in a cramped hall, and there was a choice of three doors leading from it. One of these was ajar, and seemed to be a cloakroom.

“In here, then we’ll see which door she goes through.”

Nor did they delay, for the masculine tread of Selina Place came to them out of the mist.

“Now let us do what we can in haste,” she said as she rejoined Grimnir. “There may be nothing threatening, but we shall not feel safe until we are master of the stone. Give it to us now.”

Grimnir unfastened a pouch at his waist, and from it drew Susan’s bracelet. Firefrost hung there, its bright depths hidden beneath a milky veil.

The Morrigan took the bracelet and placed it in the middle of the circle on the floor. She pulled the curtains over the windows and doors, and went to stand by the brazier, whose faint glow could hardly push back the darkness. She took a handful of powder from the silver plate and, sprinkling it over the coals, cried in a loud voice:

“Demoriel, Carnefiel, Caspiel, Amenadiee!!”

A flame hissed upwards, filling the room with ruby light. Shape-shifter opened the book and began to read.

“Vos omnes it ministri odey et destructiones et seratores discorde …”

“What’s she up to?” said Susan.

“I don’t know, but it’s giving me gooseflesh.”

“… eo quod est noce vos coniurase ideo vos conniro et deprecur …”

“Colin, I …”

“Sh! Keep still!”

“… et odid fiat mier alve …”

Shadows began to gather about the folds of velvet tapestry in the furthest corners of the room.

For thirty minutes Colin and Susan were forced to stand in their awkward hiding-place, and it took less than half that time for the last trace of enthusiasm to evaporate. They were where they were as the result of an impulse, an inner urge that had driven them on without thought of danger. But now there was time to think, and inaction is never an aid to courage. They would probably have crept away and tried to find Cadellin, had not a dreadful sound of snuffling, which passed frequently beneath the cloakroom window, made them most unwilling to open the outer door.

And all the while Shape-shifter’s chant droned on, rising at intervals to harsh cries of command.

“Come Haborym! Come Haborym! Come Haborym!”

Then it was that the children began to feel the dry heat that was soon to become all but intolerable. It bore down upon them until the blood thumped in their ears, and the room spun sickeningly about their heads.

“Come Orobas! Come Orobas! Come Orobas!”

Was it possible? For the space of three seconds the children heard the clatter of hoofs upon bare boards, and a wild neighing rang high in the roof.

“Come Nambroth! Come Nambroth! Come Nambroth!”

A wind gripped the house by the eaves, and tried to pluck it from its sandstone roots. Something rushed by on booming wings. The lost voices of the air called to each other in the empty rooms, and the mist clung fast and did not stir.

“Coniuro et confirmo super vos potentes in nomi fortis, metuendissimi, infandi …”

Just at the moment when Susan thought she must faint, the stifling heat diminished enough to allow them to breathe in comfort; the wind died, and a heavy silence settled on the house.

After minutes of brooding quiet a door opened, and the voice of Selina Place came to the children from outside the cloakroom. She was very much out of breath.

“And … we say the stone … will … be safe. Nothing … can reach it … from … outside. Come away … this is a dangerous … brew. Should it boil over … and we … near, that … would be the end … of us. Hurry. The force is growing … it is not safe to watch.”

Mistrustfully, and with many a backward glance, Grimnir joined her, and they went together through the doorway on the opposite side of the hall, and their footsteps died away.

“Well, how do we get out of this mess?” said Colin. “It looks as though we’re stuck here until she calls these animals off, and if she’s going to do any more of the stuff we’ve been listening to, I don’t think I want to wait that long.”

“Colin, we can’t go yet! My Tear’s in that room, and we’ll never have another chance!”

The air was much cooler now, and no sounds, strange or otherwise, could be heard. And Susan felt that insistent tugging at her inmost heart that had brushed aside all promises and prudence when she stared at the mist from the bridge by the station.

“But Sue, didn’t you hear old Place say that it wasn’t safe to be in there? And if she’s afraid to stay it must be dangerous.”

“I don’t care: I’ve got to try. Are you coming? Because if not, I’m going by myself.”

“Oh … all right! But we’ll wish we’d stayed in here.”

They stepped out of the cloakroom and cautiously opened the left-hand door.

The dull light prevented them from seeing much at first, but they could make out the table and the reading-desk, and the black pillar in the centre of the floor.

“All clear!” whispered Susan.

They tiptoed into the room, closed the door, and stood quite still while their eyes grew accustomed to the light: and then they saw.

The pillar was alive. It climbed from out the circle that Selina Place had so laboriously made, a column of oily smoke; and in the smoke strange shapes moved. Their forms were indistinct, but the children could see enough to wish themselves elsewhere.

Even as they watched the climax came. Faster and faster the pillar whirled, and thicker and thicker the dense fumes grew, and the floor began to tremble, and the children’s heads were of a sudden full of mournful voices that reached them out of a great and terrible distance. Flecks of shadow, buzzing like flies, danced out of the tapestries and were sucked into the reeking spiral. And then, without warning, the base of the column turned blue. The buzzing rose to a demented whine – and stopped. The whole swirling mass shuddered as though a brake had been savagely applied, lost momentum, died, and drooped like the ruin of a mighty tree. Silver lightnings ran upwards through the smoke: the column wavered, broke, and collapsed into the ball of fire that rose to engulf it. A voice whimpered close by the children and passed through the doorway behind them. The blue light waned, and in its place lay Firefrost, surrounded by the scattered remnants of Shape-shifter’s magic circle.

Colin and Susan stood transfixed. Then slowly, as if afraid that the stone would vanish if she breathed or took her eyes off it, Susan moved forward and picked it up.