Полная версия

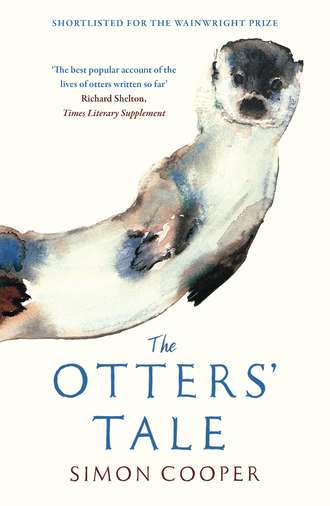

The Otters’ Tale

To find her place within this singularly convoluted riverine society, Kuschta established a pattern whilst alone during the summer and autumn months, exploring and testing each new place she came across. Sniffing tell-tale marks, she was now old enough to make a swift decision whether to move on or stay. Moving on was always her first choice because it involved least risk of confrontation, whilst staying was more nuanced, but on one particular night her luck changed.

Kuschta sat for a while at the base of the ash tree at the end of the promontory where the river split; she was perplexed. Everything she’d ever learnt told her this junction pool was a classic boundary marker, a feature in the river landscape that all otters would recognise and mark accordingly. But she had been up and down, crisscrossing the entire isthmus to check for signs of other otters, and … nothing. So if her nose told her nothing, maybe her ears would reveal some other presence, for otters have acutely sensitive hearing. To look at their tiny ears you wouldn’t think so, but I’ve frequently learnt this to my cost – until they dismissed it as benign, the slightest click of a door lock from my mill in the dead of the night was enough to scare the otters away before I ever saw them. No wonder that for me and so many others they can be such elusive creatures.

Otter hearing breaks down into two categories: in air good, in water bad. Despite water being such a good conductor of soundwaves, otters are not adapted for underwater hearing like, say, a dolphin or some seals, and in fact the auricle – the furry, half-moon visible part of the ear outside of the head – has a reflex response, closing over the ear hole when the otter submerges. Beneath the surface, touch, smell and sight are more potent senses. In air it is an altogether different story because otters have a range of hearing that is far more sensitive than that of humans, taking in a spectrum of high-pitched sounds something akin to that of a dog. For a creature that lives by the night and which has vision limited to movement and blurry shadows, acute hearing makes perfect sense.

After a long while of waiting, Kuschta had heard nothing beyond the usual night sounds, so with no real way of telling which was best, she took the right-hand fork; it was smaller than the other side but the stream appealed to her, the overgrown banks seemingly untrodden by human or otter. From her low viewpoint she couldn’t see far, but the dense reeds, interspersed with stunted alders crowding in up to the river edge, gave her a comforting sense of protection. At its narrowest point the reeds had fallen across the stream, supporting each other at the middle, creating a cathedral-arch-like tunnel that stretched into the darkness.

The mass of vegetation barred any further progress along the bank, which suited her just fine. Otters are not ideally built for walking or running; watch them move anything faster than ambling pace and you’ll see their back end rise and fall in a sort of jerky, lolloping, uncomfortable way. You worry that with all the strength in their hindquarters the front end won’t stand the strain, or at the very least the otter will tumble into an involuntary front roll as the rear end overtakes the front. Otters are a bit of a mammal oddity; a creature that lives on land but is really best adapted to life in the water. They clearly know this – in all the years I’ve lived amongst otters they have never tried to outrun me for any distance. Actually, though I’m certainly not an Olympic athlete, they couldn’t anyway, as the top otter speed is little more than fast human walking pace. When in flight, the otter tactic is clear – head for water as fast as you can. It always amuses me because they go from sheer panic on land to total confidence in the water within the blink of an eye. Once immersed, rather than swimming away into the distance at speed, they’ll take a couple of strokes to where they feel safe, surfacing to gaze back at me as if to say ‘Fooled you!’ before disappearing off.

Unless in flight, an otter is not the type of animal that hurls itself into the water. The act of movement from land to water is one of the most fluid motions you will ever see in nature. It is a sublime rendering of evolution: that moment when a creature is so totally in harmony with the many elements it occupies that you can only marvel at the grace. To say an otter pours itself into the river is no exaggeration; it is almost as if the water parts to welcome the creature home. Slipping into the water creates no alarm. Draws no attention. For an animal that relies on the element of surprise to hunt, stealth is no bad thing.

It was with this sinuous action that Kuschta moved from land to water, content in her own mind that, for once, she was perhaps entering vacant territory. Otters may be elusive but they are big, leaving distinct trails in the landscape. They may be able to enter water like a spoon sliding into honey, but getting out is something else altogether. Steep banks, together with that long, heavy frame, leave their mark – a few ins and outs at the same spot creates a slide, a muddy runway in the grassy bank. Kuschta saw no such slide. Otters are great creatures of habit in the routes they follow. Kuschta made the simple evaluation – no slides, no otters.

Cruising upstream with flicks of her webbed paws, Kuschta is barely visible, leaving only a slight silvery wake through the tunnel of reeds. As otters swim, at least nine-tenths of the body is below the surface; only the top of the head protrudes, with the nostrils open, eyes wide and ears pricked, ever alert. Sometimes, when extra effort is required, the rump and tail will appear above the surface, giving the impression of a three-humped creature, but for the most part the strong legs and tail stay beneath the surface, giving propulsion enough. Though perfectly at home in the river, the otter is an alien and ominous presence to most other river dwellers. They may be silent and invisible to people, but Kuschta’s entry into the stream created enough disturbance to frighten the small trout that were using the cover of night to feed away from the preying presence of larger fish. Alarmed by her arrival, they fled for cover amongst the roots of the reeds. All this Kuschta sensed through her whiskers, the tiny vibrations at first close, then far. But she paid them no heed. She was after bigger prey. For now she needed to move on, so as her own vibrations faded the trout headed back out in her wake to continue their search for food, life returning to normal.

After a while the reeded, scrubby bank gave way to open meadows, the river now wider and shallower. Shorn of any bank cover, the moon shone down directly on the surface, lighting a bright path of water ahead. Other than Kuschta, nothing moved or stirred. She was in that nether time of night when the chill had settled and the bats and owls were back in their roosts. The grass had turned cold damp, enough to send the furred creatures to ground – rabbits and voles care little for getting wet when there is scant prospect of warmth; they would be waiting for dawn before reappearing. The isolation suited her just fine, so she swam on strongly against the steady current, putting distance between her and the stream junction. As the river meandered first this way, then that, she began to tire, getting a little cold herself. Easing up onto a tree root that dipped down into the water on the inside of a sharp bend, she took stock.

Otters are rarely idle. Kuschta surveyed the river whilst all the while grooming herself, both the effort and the effect gradually bringing the warmth back into her body. Perched on the root, dried and rested, she could afford to take her time – she had chosen the warmest spot on the river. Otters exploit the smallest wrinkles in nature; her perch was one such wrinkle. With certain rivers, at particular times of the year, the water is considerably warmer than the air, and where the two meet a blanket of warm air, a layer no more than a foot or so thick, hugs the surface. If you ever see a ‘smoking’ river, that’s the evidence, and by inserting herself beneath the mist, close to the water, Kuschta was exploiting nature’s very own greenhouse effect.

Everything about the bend in the river screamed fish; the tapering flow on the inside bank on which she sat had just enough slack water where a fish might rest. The faster middle would be empty, the effort/reward ratio too much for any fish to bother to hold station in. The far bank, with its undercuts, back eddies, tree roots and depth, was fish heaven – they could lie in there night and day, ready to dart out to any food that drifted their way. It was time for Kuschta to make a move. Slipping into the water, she let the current carry her downstream for a few yards, then simultaneously turned and dived, pushing herself hard and fast along the inside bend, as close to the gravel river bed as she could – the closer she stayed to the bottom, the fewer options the fish had to escape; they could go left, right or up, but not down. In the dark she could see very little. But no matter; her whiskers were doing all the seeing.

She couldn’t be sure, but maybe a fish had darted off into the distance. She let it go. Her hopes were really pinned on the far bank. By her estimation the fish would be facing upstream, looking out for food, so if she came at them head-on she’d have a crucial moment of advantage as they had to turn to flee. So surfacing well upstream, she coughed in that way that otters do, noisily sucked in air and dived. Her swimming, combined with the current, moved her fast. For a short moment the fish didn’t notice her coming, her movements masked by the midstream current. But then in total alarm they knew there was something dangerous amongst them. Kuschta’s whiskers were alive with information. She lunged as a trout slipped for cover under a tree root. Her teeth grazed another that bounced off her head. She accelerated after a third but it had too much of a head start. Undeterred, she surfaced, paddled for a moment to recover and then headed down deep, preparing to get amongst the roots this time.

It is something of an irony that any fish would be best advised to do nothing when hunted by an otter; by remaining still, the chances of detection in the dark, swirling water would be next to zero. But flight is the natural instinct of fish, so otters exploit this primordial reaction to danger. The fact was, Kuschta had no exact idea where the fish lay, she just knew that they were probably hiding in the cavity beneath the tree roots, and if she could spook them their instinct for flight would lead her to them.

Rising from below and slipping between the trailing roots that hung down in the water, Kuschta’s bulk filled the confined space. Any speed advantage the fish might have had over her was gone as she drove them down a watery cul-de-sac. Was it two, three or four fish? She couldn’t really tell, such was the confusion as they tried to push past her to the safety of open water. However many it was, it didn’t really matter – she needed just one, the currents of vibration honing her in on a fish trapped between her and the bank. The soft belly of the fish gave a little as she made contact with it with her mouth before she drove her long, curved canine teeth into the flesh. The now-wounded trout flexed head and tail in unison to escape the pain and capture. Reversing out, Kuschta kept her jaws clamped tight, the backwardly curved teeth maintaining a certain grip on the struggling fish. Breaking the surface, Kuschta’s nostrils flared open to breathe in air, whilst the trout splashed and crashed about her head, in a flailing death throe now exposed to the same air. Swimming back across the river, Kuschta headed for the root perch, scrabbling up and out, sending a spray of water all around as she delivered the coup de grace, violently shaking the fish to snap its spine.

Kuschta didn’t bother to groom or preen; she ate as if her life depended on it. By the time the first fingers of the cold winter dawn showed across the meadows she was done, the leftovers just a ragged tail. It was time to hide. Her eye was drawn to a mess of dried reeds and twigs that had been gathered up then left behind by a recent flood, piled up against the base of the tree. Pawing at the pile, she exposed a gap in the web of roots at the base of the tree. Squeezing through, she found a small cavern beyond, the sides and roof made up of old, gnarled brown alder roots, most of their growing done. The floor was softer, still alive, a bed of little pink nodules ready to sprout in the spring. Dragging some of the leaf litter inside, she circled around as best she could in the tiny space, fashioning a comfortable mattress which she nestled into. Sleep was not long coming, but before Kuschta finally drifted off she sensed she might finally have found a place to call home.

CHAPTER 3

SOMETHING IN THE AIR

Winter

I’ve lived on and around rivers pretty well all my life, but it wasn’t until my fourth decade that I finally saw an otter. And even after all that waiting, that first sighting wasn’t under particularly auspicious circumstances.

I had just bought an abandoned water mill that straddles a small chalkstream in southern England, called Wallop Brook. It did, and still does, comprise two buildings – the miller’s cottage and the mill building. The former was just about habitable and the latter was really nothing more than a foursquare brick structure rising over three storeys, completely empty bar one important element: the mill wheel itself. I gleaned from the villagers (not all overly friendly when I first moved in …) that the corn-grinding mechanism had been stripped out years before, the last production sometime soon after the Second World War. A few things remained to remind a casual visitor of a past that stretched back over a thousand years – you will find the Nether Wallop Mill listed in the Domesday Book. The side wall of the building was hung with slates, faded white signwriting emblazoning in two-foot-tall letters the legend F. VINCENT’S NOTED GAME FOODS. The mill had produced both bird food for a wider market and, on a lesser scale, flour for Nether Wallop and the surrounding villages. Out in what is now the garden, where in the past sheep grazed up to the back door, there can be found a complicated array of a mill pond, pools, hatches, carriers and relief streams. It might look antediluvian to us today, but in Mr Vincent’s time, and long before that, too, these old-fashioned devices controlled the flows that were vital for driving the water wheel and sustaining the milling industry. In more modern times, and for my purposes, they are far from defunct, their control being the difference between me having a wet or dry house in times of flood.

As I write this today my feet are poked under a giant cast-iron spindle, the central core to an even more giant cast-iron mill wheel, the height of two men, that is separated from me by a low wall, topped by a glass partition to the ceiling. Effectively my office is divided in two – one half for me and the other half for the mill wheel. Despite the constant pummelling roar of the water next door (yes, every minute, of every hour, of every day, year in year out), I chose to build a desk over what used to be the drive mechanism for the grinding stones. If I look up I can see the marks in the ceiling beams where the power take off gear connected to the spindle to the grinding gear. Behind me is an old-fashioned winding handle that turns two cogs, which in turn lift an iron gate that controls the flow of water into the stream that powers the mill wheel. I only need turn the cogs two or three notches and the wheel will turn. It is a slow, powerful, creaking turn, the thirty-two buckets (the official term of a mill wheel paddle) taking nearly a minute to go full circle. I have to remember to keep my feet clear of the turning spindle when it is in motion.

But it wasn’t always like this. When I first arrived, the wheel was stopped and had been that way for years. In some distant past it had slipped out of level alignment; for a while it obviously continued to turn despite being out of kilter, cutting circular gouges in the wall that are still plain to see. But at some point it must have jumped out of the shoe in which the nub of the spindle sat, to lean at a crazy angle jammed up against the wall. The iron control gate had rusted away to nothing, the cogs that raised and lowered it long gone. You’d think that it was a hopeless case. Plenty suggested that I might just as well sell the iron for scrap. However, I am not that easily deterred. Believe it or not, there are still skilled wheelwrights working today. Men with boiler suits, toolboxes full of mighty spanners and hands perpetually ingrained with grease. They took one look at it, pronounced it sound and returned some weeks later with newly made parts that made the wheel operation whole again.

You might wonder why this is relevant to my first otter sighting. Well, there is a vaulted tunnel where the mill straddles the river, carrying away the water after it has powered through the wheel. After years of disuse that tunnel was virtually blocked. We had donned waders to check it out, jammed as it was with logs, mud, brushwood and all sorts, but really it was too dark and confined to tell much. I was all for some extreme raking to clear it, but the millwright guys assured me that the water would do all the work. So with great ceremony the iron gate was lifted for the first time in decades. The water flowed, the mill wheel turned and the tunnel gradually filled with water until the force was so great that a plug of ancient detritus burst through into the mill pool below. Suddenly the pool went from shallow and clear to deep and dirty. Tree roots, bald tennis balls, reeds, twigs and all sorts swirled in the surface, but something in the back eddy caught my eye. It looked like an over-inflated, half-sunk, part-hairy, grey and pink balloon. I dragged it closer with a stick.

I guessed it was something dead. At first I assumed it was a badger, but the long tail, denuded of hair in death, told another story. As the corpse flipped over, it was clearly an otter. I am no pathologist, but years of living in the country usually gives you some ability to tell what a creature has died of, or been killed by, but this otter was too far gone for any postmortem. The fur was peeling away, exposing the greying pink skin beneath. Bones were showing through the flesh of the legs. I suspect in a week or two it would have been unrecognisable even as an otter. So I can only surmise as to how it had died. In all probability it had crawled into the tunnel as a last place of refuge, hit perhaps by a car, which is common enough. Or maybe it was on the wrong end of a fight. Or perhaps it was simply old age. Whatever the reason, it was a sad way to see my first otter.

I must admit, at the time I didn’t think very much more about it, putting it down to a freak occurrence, but as I spent more time at my desk beside my newly refurbished mill wheel I started to have unexpected company. As I mentioned earlier, the wheel housing is a separate room of the mill, through which the river flows, splitting into two channels. One channel takes up about two-thirds of the width, over which hangs the wheel itself. The other third is the mill race, where the water pummels through. The race is a sort of relief channel through which the river is diverted when the wheel is not running. The whole wheel housing is effectively open to the elements with brick arches over the river at either end of the building. On the upriver, or inflow, side, two huge, ancient oak beams straddle the width of the room from which are hung the iron gates that control the flow through the two channels. It was these beams that the otters adopted as couches.

I say ‘the otters’, but I really have no true idea whether it was the same otter who arrived often or a series of visitors. The sightings were nearly always fleeting as I came into the room to sit at my desk; a blur caught in the corner of my eye followed by a splash. At first I ignored it, thinking it was, well, I don’t really know what I thought it was. A mink perhaps, or a stoat; they are far more common. Even a rat maybe. But one day when I was adjusting the control gates I saw shining atop one of the oak beams what today I would instantly recognise as a spraint. Back then, less so, or, if I’m being honest, not at all. A trip to my desk and a visit to Google put me right. I determined to be more discreet when entering the office next time.

However, my definition of discreet and that of an otter is a very long way apart. Two or three steps into the room was only ever the best I could do before the splash and the rapid departure. I did take to rushing outside to at least have the satisfaction of following the bubble trail as the otter headed off underwater. Sometimes he, or it could have been she, would surface to look back, but generally the last I would see was a wet sliver of fur slide itself over the weir and disappear into the pool below.

A few times I did get closer. One summer afternoon I went into the mill wheel room, blinking as I went from the bright sunshine to semi-darkness, only to be struck rigid at the sight of two otters sitting on the oak beams. Who was more shocked I have no idea. I looked at them, they looked at me. I didn’t move but they did, twisting and diving into the water, fleeing at speed. The other times were when I worked very early or very late at my desk. I’d hear some splashing and coughs of exertion as an otter hauled itself out of the water using the ironwork as a sort of ladder to perch on one of the beams, grooming and generally making itself comfortable before settling down. It was then, and still is now, a wonderful thing to see up close. Occasionally the otter would spy me, our eyes meeting and the reaction variable. Sometimes instant flight, other times mild curiosity before choosing to ignore me. The latter was fine by me. Working with an otter peering over your shoulder is an oddity worth getting used to.

It might seem odd that an otter would choose the mill wheel as such a regular stopping-off point, being, as it is, in the midst of a human habitation. But I think it is something of a combination of things that makes it so attractive – the antiquity, the lie of the land around the mill, the location and, more recently, an awful lot of fish. There is no doubt that they have been using that oak beam as a couch for a very long time. Spraints are not just odorous but are also pretty toxic in dung terms. Regular sprainting spots on grassland will turn the turf brown then dead. It will really take the ground a long while to recover, the deposits having much the same effect as spilling fuel or oil on your lawn; once you know what to look for, it is an easy way to tell whether otters are around. In a similar fashion, otters who live by the sea will take a particular liking to a prominent rock or outcrop. Clearly the spraints can’t do much damage to solid stone, but the spot will turn green in time, much like the copper roof of a church. Back closer to home, my oak beams have suffered a slightly different fate; each now has rotten indentations where the otters have laid down their marks over the years.

The land around the mill is a regular Spaghetti Junction of water courses; not only does the water go under the building but it goes around it on both sides – we are effectively moated. To put that into some sort of perspective, imagine you are looking directly at a rugby ball; from the top the three lines of stitching represent where the single river is split into three. Down the left goes the original Wallop Brook, a fast clear stream that burbles over gravel. Down the middle is a much wider, deeper slower river which we (confusingly) call the Mill Pond. It is this that drives the mill wheel, which is where the rugby ball laces would be. Down the right is a side stream, or carrier, a man-made channel that was created to regulate the level of the Mill Pond. All have been dug or adapted by man in past centuries to manage the water flow, with the addition of some connecting channels that run crossways between them. Downstream of the mill, at the base of the rugby ball, if you like, all three come back together where a united brook continues on its way into the water meadows.