Полная версия

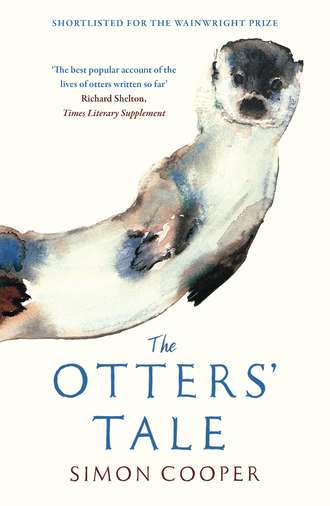

The Otters’ Tale

Copyright

William Collins

An imprint of HarperCollinsPublishers

1 London Bridge Street

London SE1 9GF

WilliamCollinsBooks.com

First published in the United Kingdom by William Collins in 2017

This William Collins eBook edition published in 2018

Text © Simon Cooper 2017

Cover illustration © Curious Otter, 2003 (w/c on paper), Adlington, Mark/Private Collection/Bridgeman Images

The author asserts his moral right to be identified as the author of this work.

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the non-exclusive, non-transferable right to access and read the text of this e-book on-screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, down-loaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins.

Source ISBN: 9780008189747

Ebook Edition © March 2018 ISBN: 9780008189723

Version: 2018-09-26

Praise for The Otters’ Tale:

‘He summarizes his observations by telling the detailed story of a mother and her young and the male otter with which they occasionally interact. He does so with the charm of a Kenneth Grahame but with the scientific rigour of modern behavioural science. It is the best popular account of the lives of otters written so far.’

Times Literary Supplement

‘Offers something new, and ultimately optimistic.’

New Scientist

‘A wonderful book.’

Daily Mail

Praise for Simon Cooper:

‘I loved the gentle flow of this book and the insight into both a pastime and a wonderful corner of the land.’

BBC Countryfile

‘Cooper’s enthusiasm is so infectious’

Daily Mail

‘[Simon Cooper] is a renowned fly-fisher himself and, in this book, he writes as well as he casts […] delightful […] Mr Cooper is in love with chalkstreams and anyone who reads this splendid book will soon hold the same view.’

Country Life

‘We are taken on a delightful journey overflowing with passages that capture our imagination […] It is both uplifting and therapeutic.’

Classic Angling

Dedication

To Mary and Minnie – muses both.

Epigraph

‘It’ll be all right, my fine fellow,’ said the Otter (to Ratty). ‘I’m coming along with you, and I know every path blindfold; and if there’s a head that needs to be punched, you can confidently rely upon me to punch it.’

Kenneth Grahame, The Wind in the Willows

Contents

Cover

Title Page

Copyright

Praise

Dedication

Epigraph

Prologue

Chapter 1 Alone and afraid

Chapter 2 A place to call home

Chapter 3 Something in the air

Chapter 4 Alone but determined

Chapter 5 And then there were five

Chapter 6 And then there were four …

Chapter 7 A country playground

Chapter 8 Life in the food chain

Chapter 9 To Autumn

Chapter 10 It’s a dangerous life

Chapter 11 Solstice

Chapter 12 Lutran’s tale

Chapter 13 Coming of age

Chapter 14 The long journey

Epilogue

Footnote

Bibliography

Acknowledgements

Index

About the Author

About the Publisher

PROLOGUE

Looking back on it, I was something of a fool; the signs had been there for years but it took a fall of January snow finally to reveal what I should have known all along. As night turned into day, the virgin snow around the lake was anything but virgin, the peninsula that divided the lake from the river criss-crossed with seemingly a thousand footprints or more. From river to lake, lake to river and back again, the night-time visitors had clearly been busy, the five clawed paw prints exposing the green grass beneath the broken snow. This animal runway was as churned up as any busy city-centre pavement, but with particularities that told its own unique tale.

The river bank spoke of great effort, the snow ground into mud. Deep impressions in the turf atop the bank were clearly purchase points, the lower bank a mess of icy earth where the creatures had scrabbled to haul themselves from the water. Where the track marks met the lake was a different story. An icy slide, which looked as fun as that of any water park, was worn smooth with regular use, forming the connection between land and water. At the approach a patch of snow, maybe the size of a large door mat, was crushed flat – smooth evidence, to my mind at least, of someone or something lying and rolling in the snow.

In the dull light of pre-dawn one corner of battered snow beneath the tall alder caught my eye. It looked different to the rest and, sure enough, as I approached I could see the mottled snow was flecked with blood, with a bright red patch at its centre. Little bright silvery grey specks, at first unfamiliar, decorated this collage of nature. I stooped down, licked my finger and dabbed at one. A fish scale, shining like translucent mother-of-pearl, glinted back at me. The cogs in my head were gradually clicking into alignment.

A raspy, wheezy cough cut through the silence, and there, at the base of the alder, on the roots that formed a sinewy platform at the lake edge, sat the otter that I would one day know as Kuschta. In truth, she seemed calmer about our accidental meeting than I was. In that fraction of a second in which our eyes locked she assessed me, dismissed me as irrelevant and then turned, in one fluid movement pouring herself into the lake. I, on the other hand, stood rooted to the spot, uncertain what to say or do. I mean really, how daft is that – what could you ever say to an otter? Or do? Well, I did nothing. She, clearly the more evolved one in this particular situation, surfaced a few yards out from the bank before heading for the island that sits in the middle of the lake. On reaching its edge she emitted a single eek, which was echoed a moment later by a short symphony of eeks that soon took form as four dark shapes plopped from the island into the water to join her.

From my rooted spot I could easily track the progress of the swimming party across the lake as they set course for the outflow where it joined the river at the waterfall created by the weir. The five flat, domed heads glistened against the inky blackness of the water. They were hurried rather than panicked, with the young otters swimming in a rough V formation behind their mother. As they scrambled over the weir I lost sight of each in turn, but it was a long time before I knew they were completely gone. For a while as they headed downstream I could hear them cavorting and splashing as they went, eeking to each other every few seconds in that otterly way that says, ‘Don’t worry, I’m fine, I’m still with you.’

But eventually all I had was silence and the red sky of dawn. Somewhere downstream, in the water meadows and woods that border the river, the otters would seek refuge from the day, curling up in the warm, dry comfort of a rotten tree trunk until dark. I’d lost them for now but somehow I knew they would return.

CHAPTER 1

ALONE AND AFRAID

Two years earlier

As dusk started to fall, Kuschta gradually uncoiled her body, stretching away the stiffness of a day spent asleep. Sniffing the air, she could tell the holt was empty without even opening her eyes. There was nothing unusual in that, but she was comforted by the slight warmth radiating from the indentation left by her mother in the soft bed of the rotten willow trunk which they shared. She was clearly not long gone. Kuschta weighed up her options. She guessed her mother would not be far, probably down at the weir pool diving for eels – easy pickings, as they gathered in great numbers before their summer migration to the sea.

In truth, Kuschta had options, but only of the no-win kind. On that fateful evening the outcome was to be the same, whatever her decision. Whether she stayed in the holt or went in search of her mother she was destined to greet the following dawn alone. But knowing none of that, Kuschta assumed her mother would return as she had done every day of her fourteen-month life. Maybe with a tasty eel that they would share? So oblivious to the future, Kuschta chose to stay put, recoiled herself, buried her nose in the crook of her hind leg, closed her eyes and was instantly asleep.

You could walk close by the spot where Kuschta slept and not give it a second glance. In fact, I’d hazard that even if you stopped and stared you might not be much the wiser. Otters are not like badgers, which dig elaborate setts, creating multiple cave-like entrances with the spoil of their digging spread around for all to see. In their choice of home otters are pragmatists, moving between ‘holts’, which are usually tunnels amidst the roots of trees beside the river, and ‘couches’, well-concealed resting places above ground. Neither is particularly easy to spot because they are so much a part of the landscape, used by generation after generation of otters. Twenty, thirty, forty years of continuous use is not uncommon – even a century has been recorded. This we know from otter hunts that combed every inch of bank until they were banned in the 1970s. A diligent huntsman would know every hover, as some called them, returning time and again to seek out their prey and record the locations for future hunts.

Otters are not builders like, say, beavers; they take what they find and adapt it. The best holts are created by Mother Nature. An ash or a sycamore grows tall beside the river until gravity takes a hold as the water erodes the bank beneath, so the tree starts to lean out over the river. These trees are well adapted to such a pose, the wide shallow roots providing enough support for some considerable elevations of lean. But it is in that process of tipping that the den is made; the movement lifts the bank to create a cavity under the roots, which in turn becomes the canopy of the holt. And in the otters go. Some judicious digging will create a labyrinth of dry tunnels and, if all goes according to plan, there may even be an underwater connection to the river.

Couches, on the other hand, are rather more at the making of otters, but they are, as the name suggests, the more informal of the two habitats. A pile of reeds, dry moss or leaves in a thicket of brambles a few yards from the river would be typical. It’s more of a good weather than a bad weather sort of place, though not always. In wet flood plains where dry holts are scarce, elaborate couches are created as alternative homes, but more generally the couch is the resting place where otters feel safe to sleep, catch the sun and play whilst whiling away the daylight hours, hidden from view.

I guess Kuschta would care little for my subtle differentiation between couches and holts. All she knew was that the hollowed-out crack in the willow branch had long been a favoured resting place for the family; warm, inviting and familiar. The willows that thrived by the river had this strange way of growing that helped the otters; shooting up fast, they soon outgrow themselves so much that the limbs burst or crack open lengthways before snapping away from the trunk and falling to the ground. Laid out, the cracked branches look a little like an open pea pod, and at first there would probably only be just enough room for an otter to squeeze inside the fissure in the wood. But in time the timber would start to rot from the inside out, the constant comings and goings of the otters gradually hollowing out the trunk. The bark and cortex, still connected to the mother tree, stay alive even to the extent that the bright green shoots continue to grow up to create a sort of curtain in front of the hollow. It is as natural a hiding place as you’d ever find.

It was well into the night when Kuschta woke up with a start; something or someone was passing by. She had no reason to be scared, but she was, freezing rigid until the sound faded into the distance before she raised her head to check the hollow. Empty. She pawed at the soft, rotten wood where her mother usually sat. Cold. Cold as if she had never been there. Something wasn’t right. Wishing it wasn’t so, Kuschta stared out at the river for a little while, the landscape bathed in the silver light of a half moon, until she reached a decision – she’d go to find her mother.

Parting the willow-whip curtain, Kuschta pushed herself out of the hollow and slid into the water. In her mind there was no doubt she would find her mother at the weir pool. It was one of their favourite haunts. As she swam she became more confident in her decision. Familiar landmarks marked the route. The moon lit the way. The weir was not far. Turning the last bend with it just ahead, Kuschta slowed her pace. She half expected to see the silhouette of her mother on the wooden beam that braced the right-hand side of the structure. The two of them often sat there to share the spoils, but tonight it was empty. No matter. Kuschta stopped paddling, letting the current take her along whilst straining her ears for familiar sounds above the regular pounding of the water as it crashed over the weir. Nothing.

Scrambling up, she took in the whole pool from the vantage point of the beam with one swift movement of her head. The fast plumes of water that washed to the centre of the pool then gathered together to push out and on through the mouth to continue on as one river. The gentle slope of the grassy bank that led down to the water on the far side. The line of alders on the nearside, all gaunt and black against the night sky. All utterly familiar but totally absent of the one thing she sought. Confused and deflated, Kuschta settled down on the beam to wait for her mother to return. Time was her only hope.

It is probably better that at this point Kuschta doesn’t know what we know, namely that she has been deserted by her mother forever. Deserted is a harsh word, but from such swift and brutal decisions, good will come. It’s just that sometimes it doesn’t seem that way at the time.

Otters are relatively unusual in the mammal kingdom of Britain, breaking with the norms of reproduction. In the standard way of things, offspring are born in spring, raised in the summer and go their own way by the autumn at the latest. But for otters it is somewhat different, the reproductive cycle being closer to biennial than annual, with the pups, the females in particular, staying with the mother until they are well over a year old. With so much time together, the bond between mother and pups is intense; the father is rarely a factor, moving on soon after mating. Otter pups are truly dependent on the mother; they can’t swim or hunt without being taught. But even when armed with those basics they can’t go it alone. Three months, six months, nine months, a year – they will starve without maternal oversight all the way into young adulthood.

The family group is everything in the upbringing of an otter. The litter, anywhere from one to four pups, will spend every waking and sleeping hour together with the mother until they go their separate ways. The first schism comes earlier for male pups. Approaching one year of age, he will be as big as his mother, and with increasingly unruly behaviour and becoming more dominant than she would like, the mother takes a stand against her son and drives him away. Shorn of her guidance and protection, this adolescent faces an uncertain future. Travelling alone, he has to fight for his life both in terms of finding a territory to call his own and food to live on. Mature males will care little for his intrusion and other mothers will be fiercely protective of their patch. He will find it hard to rest; the itinerant life will drain his strength as he is constantly moved on. His hunting skills are still evolving; surviving day to day in unfamiliar places is a constant battle. There are plenty for whom the battle is too much, dying of exhaustion and starvation. His sisters will eventually reach a similar fork in their lives.

Survival, and the search for food to ensure survival, can also determine otters’ habitat. Sometimes the choice of a coastal home is made of necessity, driven along to the mouth of a river in a search either for territory or for food. Otters are very ‘linear’ in their habits and outlook; they rarely stray far from water, preferring to travel great distances along watercourses rather than heading inland. The only common exception to this is the birthing holt, which, for reasons we will discover, is located well away from the water. So when an otter can’t find a territory to call his or her own, or possibly when there is not enough food, he keeps on travelling until, as with any river, he reaches the sea. Saltwater, freshwater – it is all the same to an otter. Coastlines offer the same opportunities for raising a family. Let’s face it, if your kind has been able to span so many continents and landmasses, you are going to be pretty adaptable.

It is, however, worth making a distinction here between sea otters and otters that live by the sea. Kuschta – and every single otter that has ever existed in the British Isles – is of the family Lutra lutra, more commonly referred to as the Eurasian or European otter, which is one of thirteen different known otter species around the globe. As the name suggests, the European otter is indigenous to Europe, but also to Asia and North Africa, with a truly phenomenal spread across the northern hemisphere. West to east, with a few exceptions, such as the Mediterranean islands, this species walks every landmass from the Atlantic Ocean to the Pacific Ocean. From northern Russia to the Indian Ocean, snowy Finland, dusty Morocco, the foothills of the Himalayas, humid Thailand or the frozen shores of the Bering Sea – if you know where to look, you’ll find Lutra lutra in all these lands.

On the other hand, sea otters – Enhydra lutris – are an entirely different species altogether, found along the shallow coastal waters of Russia, California and Alaska in the northern Pacific Ocean. They rarely venture onto land, living entirely in the water, and are famous for floating belly up in the kelp forest that hugs the shoreline. Conversely, British otters that live by the sea are just your normal inland otters that have picked a different type of home. In the Scottish islands, where they thrive, this way of life is the practical alternative, where there is more productive coastline than freshwater river or loch.

As the sky started to show fire red behind the grey clouds in the pre-dawn, Kuschta knew it was time to move. She had seen and heard nothing during her night-time vigil. Neither friend nor foe had broken the silence or the surface of the eel pool. Stretching her stiff body on the beam, she knew she should have used the darkness to hunt, but with the sun coming up fast it was now too late. Darkness is the friend of otters; they navigate their world in the secret time between dusk and dawn. Daylight is the time for rest, night the time for travel, food and adventure; this much Kuschta had learnt from her mother. Impelled by the rising sun, Kuschta needed to make it back to safety or at least somewhere familiar. Sliding into the water, she swam quickly upstream, sending out unruly waves that rocked at the reeds on either bank, first startling a moorhen who let out an anguished squawk of protest, and then a water vole who simply paused his weaving amongst the stems until the commotion was past. Silhouetted against her skyline, the cattle grazed in the meadows, their scrunching remarkably noisy, even to her ears. A fox trotted across a bridge, no doubt heading, just as she was, to a daytime lair. The dawn chorus was reaching fever pitch as the birds laid territorial claim to a busy day ahead. The rural community of creature kind was resetting the natural order of things as the night shift headed for bed and the day shift repopulated a valley in all the pomp of its summer plumage.

Heading for the crack willow couch, Kuschta sensed her life had changed. She had no expectation of finding a familiar body settled on the spongy, rotten wood. She was alone, and that, for now at least, was the way it would be. Pushing herself head first through the willow screen, she settled into the couch. Hunger was now her greatest concern. For a while she stared out from her hide as the river slowly woke up. A trout sipped at insects caught in the surface film. Damselflies began their hovering dance. The kingfisher took up his perch ready to feed. Bees created a symphony of buzzing as they sucked the nectar from the buttercups that blanketed the water meadows. As the familiar sounds and the warmth of the morning overtook Kuschta, she slowly drifted towards sleep, but not before resolving to find food as soon as darkness came.

It is fitting that Kuschta spent her first nights alone in the hollow of a tree, as she took her name from the myth of Native American tribes who both revered and feared otters. In legend otters dwelt in the roots of trees, transforming themselves into human form at will. In some tribes the kuschta, which literally translates as ‘root people’, were friendly and kind, leading the lost or injured to safety. But for other tribes these shape-shifters did so for evil intent, to become the stealers of souls by guile, luring the naïve or unsuspecting away from home where they were transformed into otters, thus deprived of reincarnation and the consequent promise of everlasting life that was at the core of Native American belief. Interestingly, dogs were considered the best protection against these ‘land otter people’, being the only animals the kuschta feared as their barking would force them to reveal themselves or flee. Today dogs still have a similar effect on otters.

By the time dusk arrived Kuschta was ravenous, as hungry as she had ever been in her life. In all probability she had never gone this long without food, so just as soon as the darkness felt safe she pushed out into the river. The eel pool was the obvious destination, so she swam with purpose, confident in her ability to hunt down a meal solo; after all, she’s been doing so for much of her life, but in the wild nothing is ever certain. Fish are faster than otters, which Kuschta had learnt very early on – over the first two yards a trout will always leave an otter trailing in its wake. Hours of fruitless pursuit had left her exhausted on the bank, reliant on the success of her mother or sharing with her siblings. But over time, through observation and imitation, she figured out that over ten yards, when stamina tells, the odds would start to tip in her favour. Add in a bit of stealth and suddenly she had a winning formula.