Полная версия

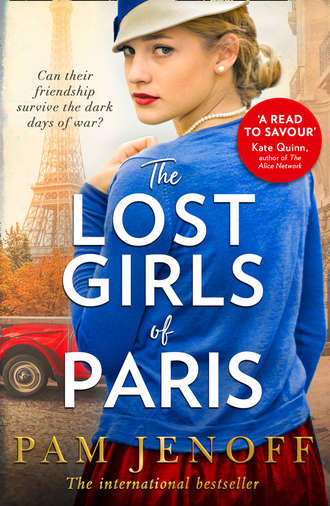

The Lost Girls Of Paris

A faint smile played about Josie’s lips and Eleanor wondered what she was dreaming. Just a young girl with a young girl’s dreams. Eleanor would let her remain that—at least for a few more hours.

She tiptoed from the room, closing the door softly behind her.

Chapter Seven

Marie

Scotland, 1944

Marie still hated running.

She had been at Arisaig House for almost six weeks and every morning it was the same: five miles up and back, partway around the loch and up a dreaded incline only known among the girls as “The Point.” Her heels were cracked and bleeding and the blisters on her feet from all of the damp hikes seemed on the constant verge of infection. Just thinking about doing it again made her bones ache.

But, she reflected as she made her way to breakfast after splashing some water on her face to freshen up, she no longer ran at the rear of the pack. Over the weeks she had been here, she had built up speed and stamina she hadn’t imagined herself to possess. She liked to keep up with Josie so that they could talk as they ran. Nothing detailed really, just a few words here or there. Josie, who had spent much of her early childhood summers in the mountains of Cumbria, would point out bits of the Scottish landscape or tell stories she’d heard from the war.

Marie had gotten to know Josie well during her weeks at training. Not just through the classes and meals; they spent long sleepless nights talking, Josie sharing stories of her childhood on the streets of Leeds with her brother, fending off scoundrels who wanted to take advantage of defenseless children. Marie shared her own past, too, of how Richard had left her penniless. She felt silly, though, complaining after all Josie had been through at such a young age. Her own childhood, while cruel, had been one of unmistakable privilege, not at all like Josie’s street urchin–like experience. The two would not have known each other in different circumstances. Yet here they had become fast friends.

In the dining hall, they took their usual spots at the women’s table, Josie at the head, Marie and Brya on either side. Marie unfolded her napkin carefully and placed it in her lap and started eating right away, mindful that Madame Poirot was, as ever, watching. Meals were constantly part of the lesson. The French wipe up their gravy with bread, she’d learned soon after arrival. And never ask for butter—they no longer have any. Even at mealtime, it seemed the girls were being scrutinized. The slightest mistake could trip you up.

Marie recalled a night shortly after she had arrived at Arisaig House when they had been served a really good wine at dinner. “Don’t drink it,” Josie had whispered. Marie’s hand froze above her glass. “It’s a trick.” For a second she thought Josie meant the drink had been poisoned. Marie lifted the wineglass and held it beneath her nose, sniffing for the hint of sulfur as she had been trained but finding none. She looked around and noticed them plying girls with a second glass, then a third. The girls’ cheeks were becoming flushed and they were chatting as if they didn’t have a care. Marie understood then that the test was to see if they would become reckless after drinking too much.

“You’re in an awful hurry,” Josie observed as they ate breakfast. “Hot date?”

“Very funny. I have to retake codes.”

Josie nodded, understanding. Marie had already failed the test for the previous unit in radio operator class once. There would not be a third chance. If she couldn’t do it today and prove that she could transmit, she would be sent packing.

What would be so bad about that? Marie mused as she ate. She had not asked for this strange, difficult life, and a not-so-small part of her wanted to fail and go home so she could see Tess.

She’d trained intensively from morning until night since coming to Arisaig House. Most of her time was spent in front of a radio set, studying to be a wireless telegraph operator (W/Ts, they were called). But she’d learned other things, too, things she could not have possibly imagined: how to set up dead and live letter drops and the difference between the two (the former being a pre-agreed location where one agent could leave a message for another; the latter an in-person, clandestine meeting), how to identify a suitable rendezvous spot, one where a woman could plausibly be found for other reasons.

But if running had gotten easier, the rest of the training had not. Despite all she learned, it was never enough. She couldn’t set an explosives charge without her fingers shaking, was hopeless at grappling and shooting. Perhaps most worryingly, she could not lie and maintain a cover story. If she could not do that under mock interrogation, when the means of coercion were limited, how could she ever hope to do it in the field? Her one strength was French, which had been better than everyone else’s before she arrived. On all other fronts, she was failing.

Marie was suddenly homesick. Signing on had been a mistake. She could take off the uniform and turn it in, promise to say nothing and start home to Tess. Such doubts were nothing new; they nagged at her all through the long hours of lecture and at night as she studied and slept. She did not share them again, of course. The other girls didn’t have doubts, or if they did they kept them to themselves. They were resolute, focused and purposeful, and she needed to be, too, if she hoped to remain. She could not afford to show fear.

“Headquarters is here,” Josie announced abruptly. “Something must be going on.”

Marie followed Josie’s gaze upward to a balcony overlooking the dining hall where a tall woman stood, looking down on them. Eleanor. Marie had not seen the woman who had recruited her since that night more than six weeks earlier. She’d thought of Eleanor often, though, during these long, lonely weeks of training. What had made Eleanor think she could do this blasted job, or that she would want to?

Marie stood and waved in Eleanor’s direction, as though seeing an old friend. But Eleanor eyed her coolly, giving no sign of recognition. Did Eleanor remember their meeting in the toilet, or was Marie one of so many faceless girls she had recruited? At first, Marie’s cheeks stung as if slapped. But then Marie understood: she was not to acknowledge her past life or anyone in it. Another test failed. She sat back down.

“You’ve met her?” she asked Josie.

Josie nodded. “When she recruited me. She was up in Leeds, for a conference, she said.”

“She found me, too,” Brya added. “In a typing pool in Essex.” Each, it seemed, had been selected by Eleanor personally.

“Eleanor designed the training for us,” Josie said in a low voice. “And she decides where we will go and what our assignment might be.”

So much power, Marie thought. Remembering how cold and disdainful Eleanor seemed during their initial meeting in London, Marie wondered if this perhaps did not bode well for her.

“I like her,” Marie said. Despite Eleanor’s undeniable coldness, she possessed a strength that Marie admired greatly.

“I don’t,” Brya replied. “She’s so cold and she thinks she’s so much better than us. Why doesn’t she put on a uniform and fly to France herself if she can do better?”

“She tried,” Josie said quietly. “She’s asked to go a dozen times, or so I’ve heard.” Josie had an endless network of connections and sources. She made friends with everyone from the kitchen staff to the instructors and those relationships provided valuable bits of information. “But the answer is always the same. She has to remain at headquarters because her real value is here getting the lot of us ready.”

Watching Eleanor on the balcony, looking out of place and almost ill at ease, Marie wondered if it might be lonely to stand in her place, and whether she sometimes wished she was one of them.

The girls finished their breakfast swiftly. Fifteen minutes later, they slipped into the lecture hall. A dozen desks were lined three by four, a radio set atop each. The instructor had posted the assignment, a complex message to be decoded and sent. Eleanor was in the corner of the room, Marie noticed, watching them intently.

Marie found her seat at the wireless and put on the headset. It was an odd contraption, sort of like a radio on which one might listen to music or the BBC, only laid flat inside a suitcase and with more knobs and dials. There was a small unit at the top of the set for transmitting, another below it for receiving. The socket for the power adapter was to the right side, and there was a spares kit, a pocket with extra parts to the left. The spares pocket also contained four crystals, each of which could be inserted in a slot on the radio to enable transmission on a different frequency.

While the others started working on the message on the board, Marie looked down at the paper the instructor had left for her to take the retest. It was the text of a Shakespeare poem:

From this day to the ending of the world,

But we in it shall be remember’d;

We few, we happy few, we band of brothers;

For he to-day that sheds his blood with me

Shall be my brother; be he ne’er so vile,

This day shall gentle his condition:

And gentlemen in England now a-bed

Shall think themselves accursed that they were not here,

And hold their manhoods cheap whiles any speaks

That fought with us upon Saint Crispin’s day.

The message first had to be coded through a cipher. The ciphers were contained in a small satchel, each printed on an individual square of silk, one inch long by one inch wide. Each silk contained what was called a “worked-out key,” a printed onetime cipher that would change each letter to another (for example, in this key, a became m and o became w) until the whole message made no sense at all to the naked eye. Each cipher was to be used to code the message, then discarded. Marie changed the letters in the message into the code given on the cipher and wrote down the coded message. She lit a match and burned the silk cipher as she’d been taught.

Then she began to tap out the message using the telegraph key. Marie had spent weeks learning to tap out the letters in Morse code and had spent so much time practicing she had even begun to dream in it. But she still struggled to tap swiftly and smoothly and not make mistakes, as she would need to in the field.

Operating the wireless, though, was more than a matter of simple coding and Morse. During her first week of training, the W/T instructor, a young lieutenant who had been seconded to SOE from Bletchley Park, had pulled her aside. “We have to record your fist print and give you your security checks.”

“I don’t understand.”

“You see, radios are interchangeable—if someone has the coils and the crystals to set the frequency, the transmission will work. Anyone who gets his hands on those can use the radio to transmit. The only thing that lets headquarters know it is really you is your security checks and your fist print.”

The instructor continued, “First, your fist print. Type a message to me about the weather.”

“Uncoded?”

“Yes, just type.” Though it seemed an odd request to Marie, she did it without question, writing a line about how the weather changed quickly here, storms blowing through one moment and giving way to sunshine the next. She looked up. “Keep going. It can be about anything really, except your personal background. The message needs to be several lines long for us to understand your fist print.”

Puzzled, Marie complied. “There,” she said when she had filled the page with nonsense, a story about an unexpected snowstorm the previous spring that had left snow on blooming daffodils.

The transmission printed on the teletype at the front of the room. The instructor retrieved it and held it up. “You see, this is your fist print, heavy on the first part of each word with a long pause between sentences.”

“You can tell that from a single transmission?”

“Yes, although we have your other transmissions from training on file to compare.” Though it made sense, Marie hadn’t considered until that moment that they might have a file on her. “But really, it doesn’t change from session to session. You see, your fist print is like your handwriting or signature, a style that identifies your transmission as uniquely you. How hard you strike the transmission key, the time and spacing between letters. Every radio agent has her own fist print. That’s one of the ways we know it is you.”

“Can I vary my fist print as kind of a signal if something is wrong?”

“No, it is very hard to communicate unlike oneself. Think about it—you don’t choose your handwriting consciously. It just flows. If you wanted to write really differently, you might need to switch to your nondominant hand. Same with your fist print—it’s subconscious and you can’t really change it. Instead, if something is wrong, you must let us know in other ways. That’s what the security checks are for.”

The instructor had gone on to explain that each agent had a security check, a built-in quirk in her typing that the reader would pick up to know that it was her. For Marie, it was always making a “mistake” and typing p as the thirty-fifth letter in the message. There was a second security check, too, substituting k where a c belonged every other time a k appeared in the message. “The first security check is known as the ‘bluff check,’” the instructor explained. “The Germans know we have checks, you see, and they will try to get yours out of you. You can give away the bluff check if questioned.” Imagining it, Marie shuddered inwardly. “But it’s the second check, the true check, that really verifies the message. You must not give it up under any circumstances.”

Marie completed the retest now, making sure to include both her bluff and true checks. She looked behind her. Eleanor was still there and she seemed to be watching her specifically. Pushing down her uneasiness, Marie started on the assignment on the board, picking up speed as she worked through the longer message with a new silk cipher. A few minutes later, Marie finished typing the message. She looked up, feeling pleased.

But Eleanor ripped the transmission off the teletype and strode toward her with a scowl. “No, no!” she said, sounding frustrated. Marie was puzzled. She had typed the message correctly. “It isn’t enough to simply bang at the wireless like a piano. You must communicate through the radio and ‘speak’ naturally so that your fist print comes through.”

Marie wanted to protest that she had done that, or at least ask what Eleanor meant. But before she had the chance, Eleanor reached over and yanked the telegraph key from the wireless. “What on earth!” Marie cried. Eleanor did not answer but picked up a screwdriver and continued dismantling the set, tearing it apart piece by piece with such force that screws and bolts clattered across the floor, disappearing under the tables. The other girls watched in stunned silence. Even the instructor looked taken aback.

“Oh!” Marie cried, scrambling for the pieces. She realized in that moment she felt a kind of connection to the physical machine, the same one she had worked with since her arrival.

“It isn’t enough just to be able to operate the wireless,” Eleanor said disdainfully. “You have to be able to fix it, build it from the ground up. You have ten minutes to put it together again.” Eleanor walked away. Marie’s anger grew. This was more than payback for her earlier outburst; Eleanor wanted her to fail.

Marie stared at the dismantled pieces of the wireless set. She tried to recall the manual she’d studied at the beginning of W/T training, trying to envision the inside of the wireless set in her mind. But it was impossible.

Josie came to her side then. “Start here,” she said, righting a piece of the machine’s base that had fallen on its side and holding it so that Marie could reattach the baseplate. As she worked, the other girls stood and helped to gather the pieces that had scattered, going on hands and knees for the missing bolts. “Here,” Josie said, handing her a knob that screwed into the transmitter. She managed to tighten a screw Marie was struggling with, her tiny fingers quick and deft. Josie pointed to a place where she had not inserted a bolt just right.

At last the machine was reassembled. But would it transmit? Marie tapped the telegraph key, waited. There was a quiet click, a registering of the code she had entered. The radio worked once more.

Marie looked up from her work, wanting to see Eleanor’s reaction. But Eleanor had already left.

“Why does she hate you so much?” Josie whispered as the others returned to their seats.

Marie didn’t answer. Her spine stiffened. Not bothering to ask permission, Marie stormed from the hall, looking into doorways until she found Eleanor in an empty office, reviewing a file. “Why are you so hard on me? Do you hate me?” Marie demanded, repeating Josie’s question. “Did you come here just to finish me off?”

Eleanor looked up. “This isn’t personal. You either have what it takes or you don’t.”

“And you think I don’t.”

“It doesn’t matter what I think. I’ve read your file.” Until that moment, Marie had not considered what it might say about her. “You are defeating yourself.”

“My French is as good as any of the others, even the men.”

“It is simply not enough to be as good as the men. They don’t believe we can do this and so we have to be better.”

Marie persisted, “My typing is getting quicker by the day, and my codes...”

“This isn’t about the technical skills,” Eleanor interjected. “It’s about the spirit. Your radio, for example. It isn’t just a machine, but it is an extension of yourself.”

Eleanor reached down for a bag by her feet that Marie had not noticed before and held it out. Inside were Marie’s possessions that she had arrived with that first night, her street clothes and even the necklace from Tess. Her belongings, the ones that she had stowed in the locker at the foot of her bed, had been taken out and packed. “It’s all there,” Eleanor said. “You can change your clothes. There will be a car out front in one hour, ready to take you back to London.”

“You’re kicking me out?” Marie asked, disbelieving. She felt more disappointed than she might have imagined.

“No, I’m giving you the choice to leave.” She could have left anytime, Marie realized; it wasn’t as if she’d enlisted. But Eleanor was holding the door open, so to speak. Inviting her to go.

Marie wondered whether it was some sort of test. But Eleanor’s face was earnest. She was really giving Marie the chance. Should she take it? She could be back in London tomorrow, be with Tess by the weekend.

But curiosity nagged at her. “May I ask a question?”

Eleanor nodded. “One,” she said begrudgingly.

“If I stay, what would I actually be doing over there?” For all of the training, the actual mission in the field was still very difficult to see.

“The short answer is that you are to operate a radio, to send messages to London for the network about operations on the ground, and to receive messages about airdrops of personnel and supplies.” Marie nodded; she knew that much from training. “You see, we are trying to make things as difficult as possible for the Germans, slow their munitions production and disrupt the rail lines. Anything we can do to make it easier for our troops when the invasion comes. Your transmissions are critically important in keeping communications open between London and the networks in Europe so they can do that work. But you might be called on in dozens of other ways as well. That is why we must prepare you for anything.”

Marie started to reach for the bag, but something stopped her. “I put the radio back together. The other girls helped a good deal, too,” she added quickly.

“That’s quite good.” Eleanor’s face seemed to soften a bit. “Well done, too, with the rat during explosives training.” Marie hadn’t realized Eleanor had been watching. “The others were startled. You weren’t.”

Marie shrugged. “We’ve had plenty in our house in London.”

Eleanor looked at her evenly. “I would have thought your husband dealt with them.”

“He did, that is he does...” Marie faltered. “My husband’s gone. He left when our daughter was born.”

Eleanor didn’t look surprised and Marie wondered if she had learned the truth during the recruitment process and already knew. She didn’t think Josie would have told. “I would say I’m sorry, but if that’s the kind of scoundrel he is, it sounds like you are better off without him.”

The thought had crossed Marie’s mind more than once. There were lonely times, nights racked with self-doubt as to what she had done to make him leave, how she would ever survive. But in the quiet moments of the night as she nursed Tess at her breast, there came a quiet confidence, a certainty in knowing she could only rely on herself. “I suppose I am. I’m sorry I didn’t say anything sooner.”

“Apparently,” Eleanor said drily, “you are capable of maintaining a cover story after all. We all have our secrets,” she added, “but you should never lie to me. Knowing everything is the only way for me to keep you safe. I suppose, it doesn’t matter, though. You’re leaving, remember?” She held out the bag containing Marie’s clothes. “Go change and turn in your supplies before the car arrives.” She turned back to the file she had been reviewing and Marie knew that the conversation was over.

When Marie returned to the barracks, W/T class had ended and the others were on break. Josie was waiting for her, folding clothes on her neatly made bed. “How are you?” she asked with just a hint of sympathy in her voice.

Marie shrugged, not quite sure how to answer. “Eleanor said I can leave if I want.”

“What are you going to do?”

Marie dropped to the edge of the bed, her shoulders slumped. “Go, I suppose. I never had any business being here in the first place.”

“You never had a good reason to be here,” Josie corrected unsentimentally, still folding clothes. Her words, echoes of what Eleanor had said, stung Marie. “There has to be a why. I mean, take me, for instance. I’ve never really had a place to call home. Being here is just fine for me. It’s what they want, you know,” Josie added. “For us to quit. Not Eleanor, of course, but the blokes. They want us to prove that they were right—the women don’t have what it takes after all.”

“Maybe they are right,” Marie answered. Josie did not speak, but pulled a small valise out from under her bed. “What are you doing?” she asked, suddenly alarmed. Surely Josie, the very best of them, had not been asked to leave SOE school. But Josie was placing her neatly folded clothes in the suitcase.

“They need me to go sooner,” Josie said. “No finishing school. I’m headed straight to the field.”

Marie was stunned. “No,” she said.

“I’m afraid it’s true. I’m leaving first thing tomorrow morning. It isn’t a bad thing. This is what we came for after all.”

Marie nodded. Others had left to deploy to the field. But Josie had been their bedrock. How would they go on without her?

“It isn’t as if I’m dying, you know,” Josie added with a wry smile.

“It’s just so soon.” Too soon. Though Josie couldn’t say anything about her mission, Marie saw the grave urgency that had brought Eleanor all the way from London to claim her.

Remembering, Marie reached into her footlocker. “Here,” she said to Josie. She pulled out the scone she’d bribed one of the cooks to make. “I had it made for your birthday.” Josie was turning eighteen in just two days’ time. Only now she wouldn’t be here for it. “It’s cinnamon, just like you said your brother used to get you for your birthday.”

Josie didn’t speak for several seconds. Her eyes grew moist and a single tear trickled down her cheek. Marie wondered if the gesture had been a mistake. “I didn’t think after he was gone that anyone would remember my birthday again.” Josie smiled slightly then. “Thank you.” She broke the scone into two pieces and handed one back to Marie.