Полная версия

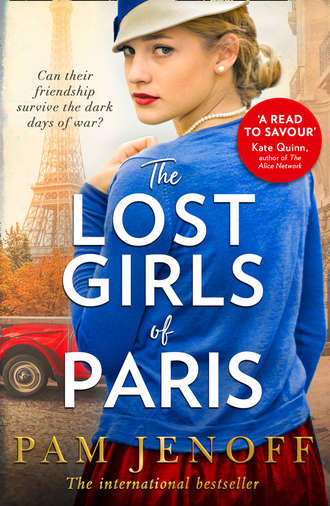

The Lost Girls Of Paris

A blonde woman about her age seated across from Marie reached over and patted her arm. “I’m Brya. Don’t let her worry you, dear.”

“In French,” Madame Poirot scolded from the doorway. Even among themselves they were to maintain the fiction they would have to portray once deployed. “Good habits start now.” Josie mimicked this last phrase, mouthing the words silently.

A whistle, shrill and abrupt, caused Marie to jump. She turned to see a burly colonel in the doorway to the dining hall. “Breakfast canceled—all of you back to barracks for inspection!” There was a nervous murmur among the girls as they started from the table.

Marie swallowed a last mouthful of baguette, then followed the others hurriedly down the corridor and up a flight of stairs to their dormitory-style room. She flung the nightdress she’d hung to dry on the radiator beneath her pillow. The colonel burst in without knocking, followed by his aide-de-camp.

Josie was staring at her oddly. It was the necklace, Marie realized. A tiny locket shaped like a butterfly on a simple gold chain, Hazel had given it to her when Tess was born. Marie had hidden it, a flagrant violation of the order that all personal belongings be surrendered at the start of training. This morning, in the scramble to get dry and dressed, she had forgotten to take it off.

Josie reached around Marie’s neck and unclasped the necklace quietly and slipped it into her own pocket. Marie started to protest. If Josie got caught with it, the necklace would be confiscated and she would be in trouble as well.

But the gesture had caught the attention of the colonel. He walked over and flung open the trunk lid and studied Marie’s belongings, seizing on her outside clothes, which she had folded neatly in the bottom. The colonel pulled out her dress and reached for the collar, where Marie had darned a small hole. He tore out the thread. “That isn’t a French stitch. It would give you away in an instant.”

“I wasn’t planning to wear it here,” Marie blurted out before realizing that answering back was a mistake.

“Having it on you if you were caught would be just as bad,” he snapped, seemingly angered by her response. “And these stockings...” The colonel held up the pair she’d worn when she’d arrived the night before.

Marie was puzzled. The stockings were French, with the straight seam up the back. What could possibly be wrong with that? “Those are French!” she cried, unable to restrain herself.

“Were French,” the colonel corrected with disdain. “No one can get this type in France anymore, or nylons at all for that matter. The girls are painting their legs now with iodine.” Anger rose in Marie. She had not been here a day; how could they expect her to know these things?

The aide-de-camp joined in, snatching a pencil from the nightstand beside Marie’s bed, which wasn’t even hers. “This is an English pencil and the Germans know it. Using this would give you away immediately. You would be arrested and likely killed.”

“Where?” Josie burst out suddenly, interrupting. All eyes turned in her direction. “We don’t ask questions,” she had admonished just a few minutes earlier at breakfast. But she seemed to do it deliberately now to draw the focus from Marie. “Where would it get me killed? We still don’t know where we are bloody well going!” Marie admired Josie’s nerve.

The colonel walked over to Josie and stood close, glowering down his nose at her. “You may be a princess, but here you’re no one. Just another girl who can’t do the job.” Josie held his gaze, unwavering. Several seconds passed. “Radio training in five minutes, all of you!” he snapped, before turning on his heel and leaving. The aide followed suit.

“Thank you,” Marie said to Josie when the others girls had left the room for training.

“Here.” Josie handed Marie back her necklace. She went to her own drawer of clothing and rummaged about, then pulled out a pair of woolen tights. “They have this kind in France, so they won’t dock you for it. They’re my last pair, though. Don’t wreck them.”

“He called you a princess,” Marie remarked as they straightened out the belongings that had been set topsy-turvy during the inspection. “Is it true?” She reminded herself that she should not be asking. They were not supposed to talk about their backgrounds.

“My father was the leader of a Sufi tribe.” Marie would not have taken Josie for Indian, but it explained her darker complexion and beautiful, coal-like eyes.

“Then what on earth are you doing fighting for Britain?” Marie asked.

“A lot of our boys are fighting. There’s a whole squadron who are spitfire pilots—Sikhs, Hindus—but you don’t hear about that. I’m not supposed to be here, really,” she confided in a low voice. “But not because of my father. You see, my eighteenth birthday isn’t until next month.” Josie was even younger than she thought.

“What do your parents think?”

“They’re both gone, killed in a fire when I was twelve. It was just me and my twin brother, Arush. We didn’t like the orphanage, so we lived on our own.” Marie shuddered inwardly; it was the nightmare she feared in leaving Tess, a child left parentless. And Tess would not even be left with a sibling. “Arush has been missing in action since Ardennes. Anyway, I was working in a factory when I heard they were looking for girls, so I turned up and persuaded them to take me. I keep hoping that if I get over there, I can find out what happened to him.” Josie’s eyes had a determined look and Marie could tell that the young girl who seemed so tough still hoped against the odds to find her brother alive. “And you? What tiara are you wearing when you aren’t fighting the Germans?”

“None,” Marie replied. “I’ve got a daughter.”

“Married then?”

“Yes...” she began, the lie that she had created after Richard left almost a reflex. Then she stopped. “That is, no. He left me when my daughter was born.”

“Bastard.” They both chuckled.

“Please don’t tell anyone,” Marie said.

“I won’t.” Josie’s expression grew somber. “Also, since we are sharing secrets, my mother was Jewish. Not that it is anyone’s business.”

“The Germans will make it their business if they find out,” Brya chimed in, sticking her head in the doorway and overhearing. “Hurry now, we’re late for radio training.”

“I don’t know why I’m here,” Marie confessed when it was just the two of them once more. She had signed up largely for the money. But what good was that if it cost her life?

“None of us do,” Josie replied, though Marie found that hard to believe. Josie seemed so strong and purposeful. “Every one of us is scared and alone. You’ve said it aloud once. Now bury it and never mention it again.

“Anyway, your daughter is your reason for being here,” Josie added as they started for the doorway. “You’re fighting for her and the world she will live in.” Marie understood then. It was not just about the money. To create a fairer world for Tess to grow up in; now, that was something. “In your moments of doubt, imagine your daughter as a grown woman. Think then of what you will tell her about the part you played in the war. Or as my mother said, ‘Create a story of which you will be proud.’”

Josie was right, Marie realized. She had been made all her life, first by her father and then Richard, to feel as though she, as a girl, had no worth. Her mother, though loving, had done little through her own powerlessness to correct that impression. Now Marie had a chance to create a new story for her daughter. If she could do it. Suddenly Tess, the one thing that had held her back, seemed to propel her forward.

Chapter Six

Eleanor

Scotland, 1944

Eleanor stood at the entrance to the girls’ dormitory, listening to them breathe.

She hadn’t been planning to come north to Arisaig House. The trip from London wasn’t an easy one: two train transfers before the long overnight that reached the Scottish Highlands that morning at dawn. She hoped the sun might break through and clear the clouds. But the mountains remained shrouded in darkness.

Upon arrival, she slipped into Arisaig House unannounced, but for showing her identification to the clerk at the desk. There was a time to be seen and a time to keep hidden from sight. The latter, she’d decided. She needed to see herself how the training was going with this lot, whether or not the girls would be ready.

It was a cool midmorning in March. The girls had finished radio class and were making their way to weapons and combat. Eleanor watched from behind a tree as a young military officer demonstrated a series of grappling moves designed to escape a choke hold. Hand-to-hand combat training had been one of the harder-fought struggles for Eleanor—the others at Norgeby House had not thought it necessary for the women, arguing that they would not possibly find themselves in a situation where it was needed. But Eleanor had been firm, bypassing the others and going straight to the Director to make her case: the women would be in exactly the same position as the men; they should be able to defend themselves.

She watched now as the instructor pointed out the vulnerable spots (throat, groin, solar plexus). The instructor gave an order, which Eleanor could not hear, and the girls faced each other with empty hands. Josie, the scrappy young Sikh girl they’d recruited from the north, reached up and grabbed Marie in a choke hold. Marie struggled, seeming to feel the limits of her own strength. She delivered a weak jab to the solar plexus. It was not just Marie who struggled; almost all of the girls were ill at ease with the physicality of the drill.

The doubts that had brought Eleanor north to check on the girls redoubled. It had been three months since they had dropped the first of the female recruits into Europe. There were more than two dozen deployed now, scattered throughout northern France and Holland. From first, things had not gone smoothly. One had been arrested on arrival. Another girl had her radio dropped into a stream and she had to wait weeks until a second could be sent to begin transmitting. Still others, despite the months of training, were simply unable to fit in and pass as Frenchwomen or maintain the fiction of their cover stories and had to be recalled.

Eleanor had fought for the girls’ unit, put forth the idea and defended it. She had insisted that they receive the very same training, just as rigorous and thorough as the men. Watching them struggle in training now, though, she wondered if perhaps the others had been right. What if they simply didn’t have what it took?

A shuffling behind Eleanor interrupted her thoughts. She turned to find Colonel McGinty, the senior military official at Arisaig House, standing behind her. “Miss Trigg,” he said. They had met once before when the colonel had come to London for a debriefing. “My aide told me you were here.” So much for quiet arrivals. Since taking charge of the women’s unit, Eleanor’s reputation and profile within SOE had grown in ways that made it difficult to operate discreetly.

“I’d prefer the girls not know, at least not yet. And I’d like to review all of their files when I’m done here.”

He nodded. “Of course. I’ll make arrangements.”

“How are they doing?”

The colonel pursed his lips. “Well enough, I suppose, for women.”

Not good enough, Eleanor fought the urge to scream. The women needed to be ready. The work they would be doing, delivering messages and making contact with locals who could provide safe houses for weapons or fleeing agents, was every bit as dangerous as the men’s. She was sending them into Occupied France and several of them into the Paris area, a viper’s nest controlled by Hans Kriegler and his notorious intelligence agency, the SD, whose primary focus was finding and stopping agents exactly like the girls. They would need every ounce of wit, strength and skill to evade capture and survive.

“Colonel,” she said finally. “The Germans will not treat the women any more gently than the men.” She spoke slowly, trying to contain her frustration. “They need to be ready.” They needed this group of girls on the ground as soon as possible. But sending them before they were ready would be a death sentence.

“Agreed, Miss Trigg.”

“Double their training, if necessary.”

“We’re using every spare minute of the day. But as with the men, there are some who simply aren’t suited.”

“Then send them home,” she said sharply.

“Then, ma’am, there would be none.” These last words were a dig, echoing the sentiments of the officers at Norgeby House that the women would never be up to the task. He bowed slightly and walked away.

Was that true? Eleanor wondered, as she followed the girls from the field where they’d practiced grappling to the nearby firing range. Surely they could all not be so unfit for the job.

A new instructor was working with them now, showing them how to reload a Sten gun, the narrow weapon, easily concealed, that some of them might use in the field. The women, as couriers and radio operators, would not be issued guns as a rule. But Eleanor had insisted they know how to use the kinds of weapons they might encounter in the field. Eleanor followed at a distance. Josie’s hands were sure and swift as she loaded ammunition into the gun, then showed Marie how to do it. Though younger, she seemed to have taken Marie under her wing. Marie’s fingers were clumsy with the weapon and she dropped the ammunition twice before managing to get it in place. Eleanor watched the girl, doubts rising.

Several minutes later, a bell rang eleven thirty. The girls moved in a cluster, leaving the weapons field and starting for a barn on the corner of the property. Keep the girls busy, that was the motto during training. No time to worry or think ahead, or to get into trouble.

Eleanor followed them from a distance so they would not notice. The converted barn, which still had bits of hay on the floor and smelled faintly of manure, was an outpost of Churchill’s Toyshop, the facility in London where gadgets designed for the agents were made. Here, the girls learned about the makeup compacts that hid compasses and lipstick containers that were actually cameras—things that each would be issued just prior to deployment.

“Don’t touch!” Professor Digglesby, who oversaw the toyshop, admonished as one of the girls went too near to a table where the explosives were live. Unlike the other instructors, he was not military, but a retired academic from Magdalen College, Oxford, with white hair and thick glasses. “Today we are going to learn about decoys,” he began.

Suddenly a loud shriek cut through the barn. “Aack!” a girl called Annette cried, running for the door. Eleanor stepped back so as not to be seen, then peered through the window to see what had caused the commotion. The girls had scattered, trying to get as far away as possible from one of the tables where a rat perched in the corner, seeming strangely unafraid.

Marie did not run, though. She crept forward carefully, so as not to startle the rat. She grabbed a broom from the corner and raised it above her head, as if to strike a blow. “Wait!” Professor Digglesby said, rushing over. He picked up the rat, but it didn’t move.

Marie reached out her hand. “It’s dead.”

“Not dead,” he corrected, holding it up for the others to see. The girls inched closer. “It’s a decoy.” He passed the fake rat around so the girls could inspect it.

“But it looks so real,” Brya exclaimed.

“That’s exactly what the Germans will think,” Professor Digglesby replied, taking back the decoy and turning it over to reveal a compartment on the underbelly where a small amount of explosives could be placed. “Until they get close.” He led them outside, then walked several meters away into the adjacent field and set down the rat. “Stay back,” he cautioned as he rejoined the group. He pressed a button on a detonator that he held in his hand and the rat exploded. A murmur of surprise rippled through the girls.

Professor Digglesby walked back into the workshop and returned with what appeared to be feces. “We plant detonators in the least likely of places,” he added. The girls squealed with disgust. “Also fake,” he muttered good-naturedly.

“Holy shit!” Josie said. A few of the others giggled. Professor Digglesby looked on disapprovingly, but Eleanor could not help but smile.

Then the instructor’s expression turned grave. “The decoys may seem funny,” he said. “But they are designed to save your life—and to take the enemy’s.”

As Professor Digglesby herded the girls back inside the barn to learn more about hidden explosives, Eleanor made her way to the manor and asked for the records room and a tray for tea. She spent the rest of the day sitting at a narrow desk beside a file cabinet on the third floor of Arisaig House, reviewing records on the girls.

There was a file on each, meticulous notes dating from her recruitment through each day of training. Eleanor read them all, committing the details to memory. “The girls,” they were called, as though they were a collective, though in fact they were so very different. Some had been at Arisaig House for just a few weeks; others were about to graduate on to finishing school at Beaulieu, a manor in Hampshire, which was the last step before deployment. Each had her own reasons for signing up. Brya was the daughter of Russians, driven by a hatred of the Germans for what they had done to her family outside Minsk. Maureen, a working-class girl from Manchester, had left the funeral of her husband and enlisted to take his place.

Josie, though the youngest, was the best of this lot, perhaps the best SOE had ever seen. Her skills came from the need to survive on the street. Her hands, which had surely stolen food, were sure and swift, and she ran and hid with the speed of someone who had fled the police more than once, to avoid arrest, or perhaps being sent to a children’s home. She was whip-smart, too, with a kind of instinct that was bred, not taught. There was a tenacity in how she fought that reminded Eleanor of the dark places in her own past.

Eleanor had been just fifteen at the time of the pogrom in their village outside Pinsk. She had hidden in an outhouse while the Russians savaged their village, raping wives and mothers, and killing children before their parents’ eyes. She kept the knife under her pillow after that, sharpened it in the darkness when no one was looking. She’d watched helplessly as her mother whored herself to a Russian officer who lingered behind in the village. She’d done so in order to feed Eleanor and her stunning younger sister, Tatiana, who had skin of alabaster and eyes that were robin’s-egg blue. But it wasn’t enough for the bastard. So when Eleanor woke up one night to find him standing over her little sister’s bed, she didn’t hesitate. She had been preparing for that moment and she knew what she had to do.

Later in the village, they would tell the story of the Russian captain who had disappeared. They couldn’t imagine that he lay buried just steps from the house, killed by the young girl who had fled with her mother and sister into the night.

But her effort to save Tatiana had come too late; she died shortly after they arrived in England, weakened by the Russian’s brutal assault. If Eleanor had only known what was happening and been able to stop it sooner, her little sister might still be here today.

Eleanor and her mother never spoke of Tatiana after that. It was just as well; Eleanor suspected that if her mother did let herself think about the daughter she had lost, she would have blamed Eleanor, who hadn’t been half as pretty or as good, for fighting back against the Russian. Everyone handled grief in their own way, Eleanor reflected now. For Eleanor’s mother it was escaping the life she had known in the old country, changing their surname to sound more English and eschewing the Jewish neighborhood of Golders Green for the tonier Hampstead address. For Eleanor, who had felt quite literally on the run since the old country, SOE had given her a place. But it was in the women’s unit that she had found her life’s work.

Eleanor analyzed each file thoroughly now. The records charted progress in each girl, to be sure, a growing sureness in marksmanship, wireless transmissions and the other skills they would need in the field. But would it be enough? In each case, it fell to Eleanor to make sure the girl had what she needed. Headquarters might deploy them too soon in the name of expediency and getting support into the field. But Eleanor would not send a single girl a moment before she was ready. And if that meant blowing the whole operation, then so be it.

Sometime later, an aide appeared at the door. “Ma’am, it’s dinnertime if you’d like to come down.”

“Please have a tray sent up.”

The next file was Marie’s. Her basic skills were competent enough, she noted from the instructor’s comments. But they described her as having a lack of focus and resolve. That was something that could not be taught or punished to overcome. She recalled watching Marie struggle earlier with weapons and grappling. Had recruiting her been a mistake? The girl had looked weak, a society girl not able to last the week in these strange circumstances. But she was a single mother raising her child in London, or at least she had been before the war. That took grit. She would test the girl tomorrow, Eleanor decided, and make the call whether to keep her or send her packing once and for all.

It was nearly eleven o’clock, well after the lights-out bell had sounded in the barracks below, when her vision blurred from too much reading and she was forced to stop. She set down the files and crept from the records room to the barracks below.

She listened to the girls’ breathing in the darkness, almost in unison. She could just make out Marie and Josie in adjacent beds, their heads tilted toward one another conspiratorially in sleep, as though they were still talking. Each girl had come from a different place, united here into kind of a team. But they would be scattered again just as quickly. They could not find their strength from one another because out in the field they would have to rely on themselves. She wondered how they would take the news tomorrow, how one would fare without the other.

The aide who had brought her food earlier came up behind her. “Ma’am, a phone call from London.”

Eleanor walked to the office he indicated and lifted the receiver to her ear. “Trigg here.”

The Director’s voice crackled across the line. “How are the girls?” he asked without preamble. “Are they ready?” It was not like him to be at headquarters so late and there was an unmistakable urgency to his voice.

Eleanor struggled with how to answer the question. This was her program and if anything was out of sorts, she would be held to blame. She could hear the men back at headquarters, saying that they had known it all along. But more important than her reputation or her pride was the girls. Their actual preparedness was all that would save them and the aims they were trying to achieve.

She pushed aside her doubts. “They will be.”

“Good. They must. The bridge mission is a go.” Eleanor’s stomach did a queer flip. SOE had taken on dozens of risky missions, but blowing up the bridge outside Paris would be by far the most dangerous—and most critical. And one of these girls would be at the center of it. “It’s good that you are there to deliver the news in person. You’ll let her know tomorrow?”

“Yes.” Of course, she would not be telling the girl everything, just that she was going. The rest would come later, when she needed to know.

Then remembering the sleeping girls, she was flooded with doubts anew. “I don’t know if she’s ready,” she confessed.

“She has to be.” They couldn’t wait any longer.

There was a click on the other end of the line and then Eleanor set the receiver back into the cradle. She tiptoed back to the girls’ dorm.

Josie was curled into a ball like a child, her thumb close to her mouth in a habit she had surely broken years ago. A wave of protectiveness broke and crested over Eleanor as she remembered the sister she had lost so many years ago. She could protect these girls in a way she hadn’t been able to her own sister. She needed them to do a job that was dangerous, potentially lethal, though, and then she needed them to come home safely. These were the only two things that mattered. Would she be able to manage both?