Полная версия

The Golden Age of Murder

Margaret’s frankness did not extend to describing how she felt about all this, but she confided in her friend, the Scottish writer Naomi Mitchison, that she ‘was made monogamous but not faithful’. She and Berkeley got on remarkably well, but even if he had designs on her, their political views were irreconcilable. Instead, she fell for Naomi’s husband Dick, an affable lawyer and future Labour MP, whose oysters-and-champagne lifestyle and baronial Scottish castle appealed to her almost as much as his personality and socialism. She described him slyly in her autobiography as ‘deceptive … because he looks so large and so respectable. He did, when I first knew him, all the things that a gentleman should, except play cricket.’ Their relationship did not jeopardize either marriage, and Margaret remained steadfast in her commitment to Douglas and their shared political values. When she wanted a break from politics, she took refuge in the Detection Club.

Notes to Chapter 5

‘snobbery with violence’

This phrase, often attributed to Alan Bennett, seems to have been coined as the title of a pamphlet published in 1932 by Count Geoffrey Potocki de Montalk (1903–1997). Colin Watson, himself a member of the Detection Club, borrowed it for his critique of pre-war thrillers and detective novels.

He remarked to a reactionary acquaintance, Colonel Farquharson

For this anecdote, I am indebted to crime novelist Keith Miles, also known as Edward Marston, who found it in L. G. Mitchell’s article ‘Murder, Univ and G. D. H. Cole’, in the University College Record, vol. xiv, no. 1 (2005).

the Liberal Party and centre-left were well represented among Golden Age authors

To take a few examples, A. E. W. Mason served briefly as Liberal MP for Coventry, and Helen Simpson campaigned as a Liberal candidate prior to her early death. Lord Gorell served in David Lloyd George’s government before defecting to the Labour Party.

One led the Jarrow Crusade, another married one of Stalin’s senior lieutenants, yet another was killed fighting for the Republican cause in Spain.

The writers concerned were Ellen Wilkinson, Ivy Low (also known as Ivy Litvinov) and Christopher St John Sprigg.

Douglas and Margaret Cole were the leading lights of the Left among Golden Age detective novelists.

The Coles’ lives have been extensively documented, with the predominant focus on their political activities. I have found Margaret’s autobiography, her biography of Douglas, and Betty Vernon’s biography of her especially valuable.

Margaret’s brother, Raymond Postgate

Postgate (1896–1971) published three crime novels in all, but neither Somebody at the Door (1943) nor The Ledger is Kept (1953) matched the success of Verdict of Twelve. His father-in-law, George Lansbury, leader of the Labour Party from 1932–35, was grandfather to Angela Lansbury, who played Jessica Fletcher in the television series Murder, She Wrote and Miss Marple in the film The Mirror Crack’d.

Freeman Wills Crofts’ novels about policemen who got results by sheer hard work

Authors whose early work shows the influence of Crofts include not only Douglas Cole and Henry Wade but also John Bude, the name under which Ernest Carpenter Elmore (1901–57) wrote a long series of detective novels.

Crofts explained his painstaking method of story construction in ‘The Writing of a Detective Novel’, reprinted in CADS 54, July 2008 with an introduction by Tony Medawar. Extensive discussion of his life and work is to be found in Curtis Evans’ Masters of the ‘Humdrum’ Mystery. ‘Humdrum’ is a term that Julian Symons applied in Bloody Murder to Crofts, Rhode and certain other novelists who ‘had some skill in constructing puzzles, nothing more’. An entertaining overview of their work is supplied in H. R. F. Keating’s Murder Must Appetize. Symons’ assessment was challenged by B. A. Pike and Stephen Leadbeatter in ‘Give a Dog a Bad Name …’, CADS 21, August 1993. Pike and Leadbeatter are champions of the ‘humdrums’, as is Evans.

T. S. Eliot rated him as the finest detective story writer to have emerged during the Twenties

See Curtis Evans, ‘Murder in the Criterion: T. S. Eliot on Detective Fiction’, in Mysteries Unlocked. Eliot’s other favourite was Richard Austin Freeman, who started writing detective stories much earlier.

Having settled a plot in outline, one spouse wrote a first draft which the couple then discussed and worked on together.

See ‘Meet Superintendent Wilson’ in Meet the Detectives. However, the extent to which the Coles’ books were joint endeavours is open to debate; see Curtis Evans, ‘By G. D. H. AND Margaret Cole?’, CADS 63, July 2012, which strives to identify the books written solely or predominantly by one or other of the Coles.

the Coles kept in touch with the working classes by engaging three servants

The Coles’ novels sometimes offered gentle satire, but penetrating social critiques tended to be in short supply. In Dead Man’s Watch (1931), for instance, the cast includes an eccentric and unpleasant husband and wife called Mr and Mrs Cole, who are members of a Pentecostal sect. Mention is made of a young unmarried woman who becomes pregnant, faints at work, and is sacked when her condition is revealed by the doctor called to attend her, but there is no hint that anyone would or should be surprised by this. Unusually, in Knife in the Dark (1941) a motive for murder is rooted in a xenophobe’s hostility towards foreign refugees; the well-evoked atmosphere of a university town in wartime compensates for a thin plot.

6

Wearing their Criminological Spurs

The first person who set out to solve ‘the riddle of the Detection Club’ was Clair Price, the London correspondent of The New York Times. Her quest led to a top-floor flat ‘in a remote suburb of London’. By this, she meant Watford. There, ‘a cloud of cigarette smoke, rising from the depths of an easy chair’ revealed the debonair presence of Anthony Berkeley. Having conducted the first press interview about the recently formed Club with its debonair but daunting founder, Price was left in no doubt whatsoever that its members were ‘neither meek nor humble’.

It was typical of Berkeley that, despite his occasional professions of misanthropy, he not only decided to create the first social network of crime writers, but also possessed the charisma and drive to transform his idea into reality. It was equally characteristic that he embarked on this initiative a mere three years after publishing his first detective novel.

Mystery has shrouded the origins of the Detection Club. Julian Symons, a historian as well as a crime writer of distinction and former Club President, mistakenly wrote that the Club started in 1932. The Club itself continues to circulate a private list of members’ details giving the same date. The misunderstanding arose because a formal constitution and rules were not adopted until 11 March 1932, but the Club effectively came into existence two years earlier, and its origins date back to 1928.

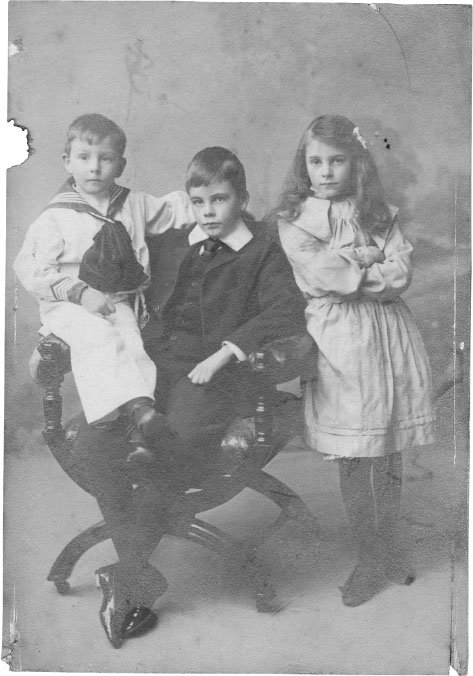

Anthony Berkeley (by permission of Celia Down).

The Cox siblings: Stephen, Anthony Berkeley, and Cynthia.

Berkeley approached several writers of detective fiction with, as John Rhode put it, ‘the suggestion that they should dine together at stated intervals for the purpose of discussing matters concerned with their craft’. He was taking a lead from the Crimes Club, a dining society focused on legal and criminological topics, with members including Sir Arthur Conan Doyle, P. G. Wodehouse, and A. E. W. Mason, a former spy and MP whose books featuring Inspector Hanaud also earned him membership of the Detection Club.

The first dinners were hosted by Berkeley and his wife Peggy, and held at their home. These were convivial occasions, and although no known records identify those who attended, it is safe to assume they included Sayers, Christie, Douglas and Margaret Cole, Ronald Knox, Henry Wade, H. C. Bailey, and John Rhode. All of them lived either in London or within easy reach, and were members of the generation of detective novelists whose careers began after the end of the war.

In the era of globalized media, when social networking by authors is encouraged by publishers to the extent that it feels almost compulsory, it is easy to forget that, in the Twenties, writers’ lives were often unconnected. Beyond small cliques whose members first met at public school or Oxbridge, writers had few opportunities to meet and talk together. Most of them prized their privacy, and not only loathed personal publicity, but kept direct contact with readers to a minimum.

‘I never supply biographical notes or photographs: a form of publicity which I deplore,’ Berkeley said, when refusing to allow his likeness to appear on Penguin paperback editions of his novels. ‘But seeing how often I myself am put off by a photograph of the author on the back of a book, I cannot but feel that some reason at any rate is on my side.’

Christie would never be so rude. She replied to fan letters by saying that she never sent out photographs of herself to anyone but personal friends, though she was willing to send autographed cards instead. Sayers took a similar line, happy to advertise her books but determined at all costs to keep her personal life under wraps. Berkeley may have been poking fun at a post-war Detection Club member, Mary Fitt (in real life, the classicist Kathleen Freeman), who did permit Penguin to publish a photograph of her, resembling a grim Borstal boy, complete with a short back and sides. In other respects Fitt, who lived with another woman, was as reticent as Berkeley: ‘It is, I think, the writer of fiction who is of interest to the public, not the person of whom the writer is part. Therefore I do not propose to give details of where I was born, where educated and so forth …’ As late as the mid-Fifties, it was perfectly credible for Christianna Brand (who was far from diffident) to conjure up a detective novel with a plot depending upon a successful writer’s hatred of personal publicity.

Keeping a distance from inquisitive strangers was one thing. A chance to meet fellow detective novelists was something special. It is no surprise that so many of those Berkeley approached leapt at the chance, just as Ngaio Marsh was thrilled to attend E. C. Bentley’s installation as President. Younger writers loved playing the game of whodunit, but that was not quite enough. Could the detective novel metamorphose into something more than a mere puzzle? Conversations over dinner at the Detection Club promoted fresh thinking, above all about collaborative writing projects.

For Sayers, as for Christie and Berkeley, the dinners offered a break from the acute stresses of their personal lives. Christie had been deserted by Archie, Berkeley wanted to be free of Margaret, and Sayers was finding Mac a trial. They were working long hours. Financial pressures meant the two women felt under pressure to write without let-up, while Berkeley was driven by the urge to show that he was as gifted as the rest of his family.

Margaret Cole was much more sociable than Douglas, and enjoyed crossing swords with intellectual equals, such as Sayers, Berkeley, and Ronald Knox, whose attitudes differed sharply from hers. They talked about real-life murder cases, crime writing, and (a constant refrain of writers the world over) the shortcomings of publishers. The dinners proved so popular that, within a year or so, about twenty writers had attended. Excited by the success of his initiative, Berkeley decided the time had come for them to organize themselves into a permanent club.

Berkeley reimagined his get-togethers as the Crimes Circle, whose activities are at the heart of The Poisoned Chocolates Case, published in 1929. The novel was an expansion of ‘The Avenging Chance’, a story often cited as an all-time classic, in which Roger Sheringham solves an ingenious murder committed by means of chocolates injected with nitrobenzene. The crime is broadly replicated in the novel, but this time Chief Inspector Moresby recounts the story to the Crimes Circle, a group of criminologists founded by Sheringham. Scotland Yard has given up hope of solving the mystery – can the amateurs do better?

Sheringham, like Berkeley, rejoiced in assembling a talented array of colleagues, and his elitist group prefigures the Detection Club: ‘Entry into the charmed Crimes Circle’s dinners was not to be gained by all and hungry.’ Membership was by election ‘and a single adverse vote meant rejection’. The intention was to have thirteen members, though only six had so far been admitted, and it is easy to imagine that plans for the Detection Club were at a similar stage of development. In addition to Sheringham, the Circle included a distinguished KC, a famous woman dramatist, ‘the most famous (if not the most amiable) living detective-story writer’, a meek little man called Ambrose Chitterwick, and ‘a brilliant novelist who ought to have been more famous than she was’.

Each of the six armchair detectives is tasked with looking into the murder of Joan Bendix and finding a culprit, and this enables Berkeley to poke fun at the methods of detective story writers. ‘Just tell the reader very loudly what he’s to think, and he’ll think it all right,’ proclaims Morton Harrogate Bradley, a crime novelist and former car salesman (like Berkeley). He makes his point by seeming to prove that he was the culprit, emphasizing: ‘Artistic proof is … simply a matter of selection. If you know what to put in and what to leave out, you can prove anything you like, quite conclusively.’

One by one, the members propound their solutions – and each identifies a different murderer. Sheringham takes fourth turn and comes up with the explanation from ‘The Avenging Chance’. He is followed by Alicia Dammers, who puts forward an even more convincing solution, which wins over all her colleagues except the diffident Chitterwick. He draws up a chart analysing the deductions of the other five members before explaining how they all went wrong. His is a classic ‘least likely culprit’ solution, delightfully revealed. Berkeley’s belief in the infinite possibilities of solutions to mysteries was confirmed half a century after the book’s publication when Christianna Brand devised yet another surprise ending to the book for an American publisher.

The Poisoned Chocolates Case is a tour de force. Julian Symons, a demanding critic, called it ‘one of the most stunning trick stories in the history of detective fiction’. Agatha Christie and P. G. Wodehouse admired each other’s work, but – regrettably – never collaborated with each other. Had they done so, they might have produced such a novel, blending wit with dazzling ingenuity. And as if to underline his cleverness while indulging in his new-found fascination with true crime, Berkeley drew a parallel between each of the solutions to the puzzle put forward by his characters and a real-life murder mystery. These included the story of Constance Kent, Carlyle Harris’s killing of his wife by morphine in New York, and the startling case of Christiana Edmunds, ‘the Chocolate Cream Poisoner’.

‘This correspondence must cease,’ declared Dr William Beard during the summer of 1870, in a frantic attempt to break off contact with a woman he had treated for nervous trouble. Christiana Edmunds had begun to frighten him. She lived quietly with her widowed mother in Brighton, but Beard failed to diagnose her long-standing mental illness, and Christiana started deluging him with letters proclaiming her devotion. Beard’s suspicions were not aroused when she turned up at his house with a box of chocolates as a present for his wife, but when his wife became sick after eating them, belatedly he put two and two together. However, Emily Beard recovered, and Beard said nothing to the police.

Christiana blamed Mrs Beard’s illness on a confectioner called Maynard, and set about acquiring supplies of strychnine from a local dentist, telling him that she meant to poison stray cats. She paid a number of boys to buy chocolate creams from Maynard’s shop, and duly laced them with strychnine, before leaving them around the town. One set of poisoned creams was returned to Maynard’s, and subsequently eaten by Sidney Barker, the four-year-old nephew of the man who bought them. Sidney died, and at his inquest, Christiana testified that she too had fallen ill after eating chocolates bought from Maynard’s. A verdict of accidental death was recorded, prompting Christiana to step up her campaign against the luckless scapegoat. She sent Sidney’s parents a series of anonymous letters blaming Maynard for the boy’s death, and gave arsenic-laced fruit and cake to a handful of local people, including the dentist who supplied the strychnine and Emily Beard. At last Dr Beard contacted the police, and showed them Christiana’s letters, although he always denied having had a sexual relationship with her. Christiana was tried at the Old Bailey for Sidney’s murder.

The Press loves nothing better than a sensational murder, and the journalists deduced homicidal tendencies from Christiana’s appearance in the dock: ‘Short of stature, attired in sombre velvet, bareheaded, with a certain self-possessed demureness in her bearing … a rather careworn, hard-featured woman … The character of the face lies in the lower features. The profile is irregular, but not unpleasing; the upper lip is long and convex; … chin straight, long, and cruel; the lower jaw heavy, massive, and animal in its development.’

Christiana was found guilty and sentenced to death. She tried to avoid the gallows by claiming that she was pregnant, a lie easily disproved, but the Home Secretary granted a reprieve on the ground of her insanity. She was sent to Broadmoor, where she made a memorable entrance, complete with rouged cheeks and an enormous wig. Thriving on her celebrity and self-image as a femme fatale, she remained incarcerated until her death, thirty-five years later.

Even before The Poisoned Chocolates Case appeared, Ronald Knox’s The Footsteps at the Lock hinted that Berkeley’s dinner parties might develop into a formal club. Knox’s story opens wittily with an account of two cousins who detest each other and are rival heirs to a fortune. They take a canoe trip together, and when one of them disappears, the other is the obvious suspect. The Indescribable Insurance Company calls in the amiable Miles Bredon to investigate. In the course of his enquiries, Bredon encounters an American called Erasmus Quirk, who says he is ‘a member of the Detective Club of America; and it was his duty to write up a detective mystery of some kind before the fall, as a condition of his membership’. Quirk, however, is not what he seems.

The pleasure of Berkeley’s dinners prompted Agatha Christie to add to her series of short stories parodying celebrated fictional detectives. ‘The Unbreakable Alibi’ sees the Beresfords tackling a puzzle in the manner of Freeman Wills Crofts’ Inspector French. She amalgamated the stories into Partners in Crime, which poked gentle fun at the detectives of twelve other writers, including eight founder members of the Detection Club, as well as Poirot. By an odd coincidence, given Conan Doyle’s interest in her disappearance, the Sherlock Holmes spoof story, written two years before she was discovered in Harrogate, was ‘The Case of the Missing Lady’. The lady in question had disappeared simply to indulge in a slimming cure.

On 27 December 1929, Berkeley wrote to G. K. Chesterton describing plans for the Club. The tone of the letter blended charm, dynamism, and impatience: ‘I do hope you will join. A club of the kind I have in mind would be quite incomplete without the creator of “Father Brown”, and one who has evolved such a very original turn to the detective story as you have … I want if possible to get things going for a first meeting in about the middle of January.’

He kept up the momentum. By 4 January 1930, a list of twelve ‘members to date’ was typed, along with a list of twenty-one writers invited to be the original members. Eight proposed Rules of the Club were sent to Chesterton, and the number of Rules grew to a dozen within days. Gathering members took time, and the Rules kept evolving. By the time the final version of the Rules and Constitution came into force, twenty-eight people had been elected to membership, although two were described as Associate Members.

With Sayers’ enthusiastic support, Berkeley asked Sir Arthur Conan Doyle to become Honorary President. Conan Doyle was the obvious choice, having created the most famous of all fictional characters, although like Douglas Cole he regarded his work in the genre as less ‘important’ than some of his other writing. The best Holmes stories belong to the nineteenth century, but Conan Doyle was still writing detective stories in the Golden Age. By now, though, his health was poor, and he could not accept Berkeley’s invitation.

Chesterton ranked second only to Conan Doyle in the pantheon of detective story writers, and he duly agreed to become President of the Detection Club. A committee was formed, and Berkeley became Honorary Secretary. He also awarded himself the title of ‘First Freeman’. This was a jokey way of distinguishing himself from R. Austin Freeman and Freeman Wills Crofts, although eventually the title’s supposed significance became a source of friction when Berkeley claimed it allowed him special privileges.

That lay far in the future. In the meantime, half a dozen members responded to an invitation from the BBC’s Talks Department to collaborate on a detective story for radio. Already, the Detection Club had earned a mention in the Daily Mirror’s gossip column – alongside snippets about horse racing and Gracie Fields’ holiday in Italy – as a dining club for writers whose stories ‘rely more upon genuine detective merit than upon melodramatic thrills’. Sayers probably fed the snippet to the newspaper. She was determined to make the public aware of the Club, and its meritocratic ethos.

The first episode of Behind the Screen aired on 14 June 1930, trumpeted in The Listener as a ‘co-operative effort on the part of six members of the well-known Detection Club’, a phrase that showed how effective Sayers’ promotional efforts had been in a short space of time. Ronald Knox brought the story to what the BBC called ‘a nerve-shattering and brain-racking conclusion’ on 19 July. Four days later, as a postscript to the serial, the BBC broadcast a conversation between Sayers and Berkeley on the subject of ‘Plotting a Detective Story’. As The Radio Times explained: ‘Miss Sayers will come to the microphone with a theme for a mystery story, Mr Berkeley with a new method of murder. They will endeavour to combine the two to form a plot for a story.’

Detection Club membership meant writers were no longer isolated when publishers annoyed them, and Sayers organized a rebuke to Collins, which launched a ‘Crime Club’ imprint for its detective fiction list, with a hooded gunman logo. Collins announced that ‘the sole and only object of the Crime Club is to help its members by suggesting the best and most entertaining detective novels of the day’. The books were supposedly chosen by a ‘panel of experts’. This was a shrewd public relations ploy, but the Crime Club was not a club in any meaningful sense. Fans’ addresses simply constituted a database for the despatch of quarterly newsletters about forthcoming titles. Detection Club members who were not published by Collins fumed at the implication that their books did not rank with the best. Sayers and Berkeley flexed their muscles with a letter to the Times Literary Supplement, signed by eight Club members. With icy understatement, they said: ‘We wish … to raise our eyebrows at a method of advertisement which is likely to mislead the public.’ Collective pressure made more impact than a moan from a single author, and although the Collins Crime Club flourished for more than half a century, its publicity became less provocative.