Полная версия

The Golden Age of Murder

Copyright

Published by Collins Crime Club

An imprint of HarperCollinsPublishers Ltd

1 London Bridge Street

London SE1 9GF

www.harpercollins.co.uk

Copyright © Martin Edwards 2015

Jacket illustration © HarperCollinsPublishers Ltd. 2015

Martin Edwards asserts the moral right to be identified as the author of this work.

A catalogue copy of this book is available from the British Library.

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the non-exclusive, non-transferable right to access and read the text of this e-book on screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, down-loaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins.

Source ISBN: 9780008105969

Ebook Edition © 2015 ISBN: 9780008105976

Version: 2015-04-20

Dedication

To the members of the Detection Club, past and present.

Contents

Cover

Title Page

Copyright

Dedication

Introduction

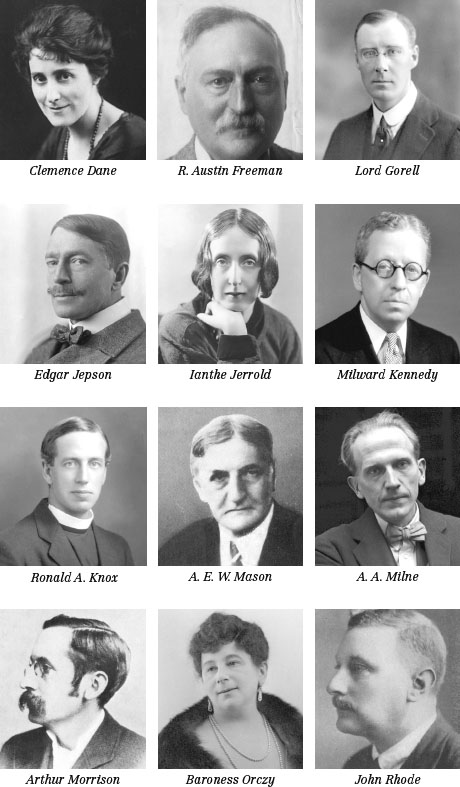

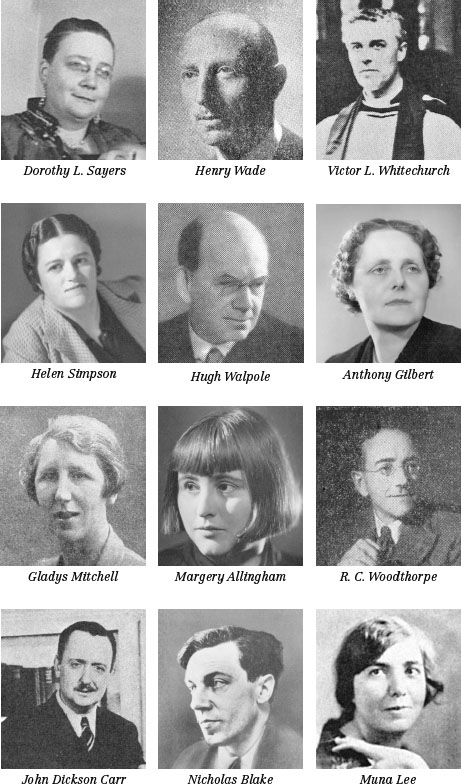

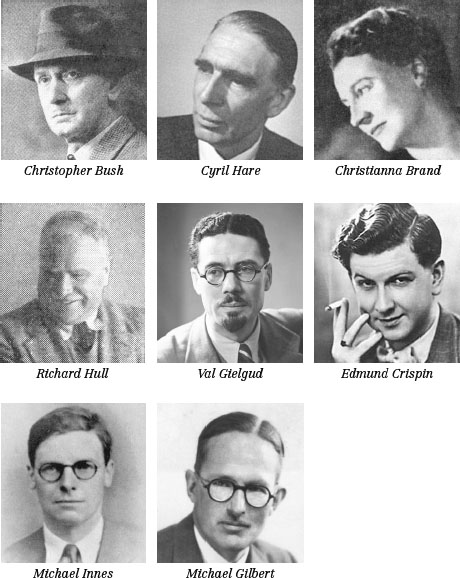

Members of the Detection Club elected 1930–49

Author Gallery

Part One: The Unusual Suspects

The Ritual in the Dark

A Bitter Sin

Conversations about a Hanged Woman

The Mystery of the Silent Pool

A Bolshevik Soul in a Fabian Muzzle

Wearing their Criminological Spurs

The Art of Self-Tormenting

Part Two: The Rules of the Game

Setting a Good Example to the Mafia

The Fungus-Story and the Meaning of Life

Wistful Plans for Killing off Wives

The Least Likely Person

The Best Advertisement in the World

Part Three: Looking to Escape

‘Human Life’s the Cheapest Thing There Is’

Echoes of War

Murder, Transvestism and Suicide during a Trapeze Act

A Severed Head in a Fish-Bag

‘Have You Heard of Sexual Perversions?’

Clearing Up the Mess

What it Means to Be Stuck for Money

Neglecting Demosthenes in Favour of Freud

Part Four: Taking on the Police

Playing Games with Scotland Yard

Why was the Shift Put in the Boiler-Hole?

Trent’s Very Last Case

A Coffin Entombed in a Crypt of Granite

Part Five: Justifying Murder

Knives Engraved with ‘Blood and Honour’

Touching with a Fingertip the Fringe of Great Events

Collecting Murderers

No Judge or Jury but My Own Conscience

Part Six: The End Game

Playing the Grandest Game in the World

The Work of a Pestilential Creature

Frank to the Point of Indecency

Shocked by the Brethren

Part Seven: Unravelling the Mysteries

Murder Goes On Forever

Appendices

Constitution and Rules of the Detection Club

Bibliography

Index

Index of Titles

Acknowledgments

About the Author

About the Publisher

Introduction

The origins of my quest to solve the mysteries of the Detection Club date back to when I was eight years old. A rich American called John L. Snyder II, who retired to the picturesque Cheshire village of Great Budworth after making a fortune in Hollywood, hosted the annual summer fete at his country house, Sandicroft. He decided to show a film in a marquee in Sandicroft’s extensive grounds – and set about pulling strings with Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer. A remarkably persuasive man, Snyder secured permission to present the world premiere of MGM’s brand new movie, Murder Most Foul.

This stranger-than-fiction initiative guaranteed publicity in the local and national Press. Snyder’s ambition was demonstrated by his search for a celebrity to open the fete. He began by approaching Brigitte Bardot, but when Brigitte declared herself unavailable (did this surprise him? I wonder), he changed tack and recruited the star of the film – Margaret Rutherford. My family lived near Great Budworth, and my parents took me to the fete as a birthday treat. So many people wanted to go that it was impossible to drive there. A fleet of coaches bussed everyone to Sandicroft.

I can still picture that afternoon among the crowds under the July sun. And I remember the excitement as a noisy helicopter circled overhead, coming in to land on a cleared patch of lawn before disgorging Margaret Rutherford, alias Miss Jane Marple. After much queuing, we squeezed into a showing of the film. Already I loved reading and writing stories, but this was my first exposure to Agatha Christie, and I was thrilled by the confection of clues and red herrings, suspects and surprises. I went home in a daze, dreaming that one day I would concoct a story that fascinated others as this light-hearted murder puzzle had fascinated me. I soon discovered the film bore little resemblance to the novel on which it was based, but that didn’t matter. I was hooked.

How fitting that my love of traditional detective fiction was inspired by a country house party in a village reminiscent of St Mary Mead. That evening, I took from a bookshelf a paperback copy of The Murder at the Vicarage, and my fate was sealed. I devoured every book Christie wrote, and tried to learn anything I could about the woman whose story-telling entranced me. In the mid-Sixties, with no internet, no social media, and not much of a celebrity culture (apart from Bardot and Margaret Rutherford, of course), finding out more about Christie proved surprisingly difficult. Eventually I moved on to other crime writers, ranging from past masters like Dorothy L. Sayers and Anthony Berkeley to Julian Symons, then at the cutting edge of the present. From Symons’ masterly study of the genre, Bloody Murder, I learned about the Detection Club, an elite but mysterious group of crime writers over which Sayers, Christie and Symons presided for nearly forty years.

Years later, I became a published detective novelist, writing books set in the here and now. A delightful moment came when a letter arrived out of the blue from Simon Brett, President of the Detection Club, explaining that the members had elected me by secret ballot to join their number. Subsequently, I was invited to become the Detection Club’s first Archivist.

The only snag was that there were no archives. Although the Detection Club once possessed a Minute Book, it has not been seen since the Blitz. Even the extensive Club library, packed with rare treasures, had been sold off.

At the time of writing, there seems little hope of ever recovering all the missing papers, in the absence of one of those lucky breaks from which fictional detectives so often benefit. But inevitably the loss of the Club’s records of its early days sharpened my curiosity. To a lover of detective stories, what more teasing challenge than to solve the mysteries of the people who formed the original Detection Club? I quickly discovered far more puzzles, especially about Christie and other early members of the Club, than I expected. I began to question my own assumptions, as well as those of critics whose judgements were often based on guesswork and prejudice.

My investigation sent me travelling around Britain, as I tracked down and interviewed relatives of former Detection Club members and other witnesses to the curious case of the Golden Age of murder. Some of the people I talked to joined in with the detective work, and the more I discovered, the more I came to believe that the story of the Club and its members demanded to be told. I explored remote libraries and dusty second bookshops, and badgered people in Australia, the United States, Japan and elsewhere in the hunt for answers. Sometimes memories proved maddeningly vague or erroneously definite. Biographies of Club members were packed with as many inconsistencies as the testimony of witnesses with something to hide.

I met with much kindness and generosity, often from those I shall never meet in person. One or two who knew secrets about the Detection Club did not want to be traced, or to recall past traumas, and this I understood. A couple of times, I reined in my curiosity when the quest risked becoming intrusive or hurtful – as Poirot recognises at the end of Murder on the Orient Express, sometimes the truth is not the only thing that matters. Exciting breakthroughs spurred me on, as when two clues, one in the form of an email address, and another discovered on my own bookshelves, led me to identify someone with personal knowledge of the dark side of one of my prime suspects.

Luck often played a part, as when I stumbled across Dorothy L. Sayers’ personal copy of the transcript of the murder trial described in The Suspicions of Mr Whicher, with pages of detailed notes in her neat hand recording her own interpretation of the evidence. Authors’ inscriptions in rare novels supplied fresh leads, and even an apparent confession by Agatha Christie to ‘crimes unsuspected, not detected’. The chance acquisition of a signed book led to my learning of a secret diary written in a unique code.

Clues to extraordinary personal secrets were hidden in the writers’ work. I sifted through the evidence with an open mind, and as real-life detectives often find, I needed to use my imagination from time to time, to fill in the inevitable gaps. Studying the work of two writers over the course of a decade and a half of their lives helped to build a convincing picture of their doomed love affair, and to understand a strange relationship that changed their lives, but has eluded all previous literary critics and their biographers. Many of the finest Golden Age sleuths sometimes relied on intuition, and what was good enough for Father Brown and Miss Marple was good enough for me. In the end, I uncovered enough of the truth to round up the prime suspects for a suitable denouement in the final chapter.

How can one discuss detective stories without giving away the endings? Some reference books contain ‘spoiler alerts’, but these can result in a fragmented read. I’ve tried not to give too much away, although in the case of a few books, readers will be able to put the pieces together.

My respect for the earliest members of the Detection Club did not diminish as I spotted flaws in their detectives’ reasoning, or chanced upon curious and sometimes embarrassing incidents in their own lives. On the contrary, I came to respect their prowess in skating over thin ice, in fiction and in everyday life. They were writing during a dangerous period in our history, years when recovery from the shocking experience of one war became overshadowed by dread of another. At this distance of time, we can see that Detection Club members had much more to say about the world in which they lived than either they acknowledged or critics have appreciated. They entertained their readers royally, but there was more to their work than that.

Even the most gifted Golden Age detectives did not work in isolation, and my own investigation benefited enormously from the help and hard work of others. My profoundest thanks go to Christie, Sayers, Berkeley and all their colleagues, who have given me so much pleasure – not only in their writing, but in the puzzles they posed as I followed their trail. That trail reaches back to the long ago July afternoon when I was lucky enough to see Miss Marple make her improbable descent from the skies, and discover a new world which, from that day to this, I have found utterly spellbinding.

Notes

Even in a book of this length, it is impossible to explore in detail every issue touched on in the text. The notes provided at the end of each chapter, inevitably selective, seek to amplify some facets of the story of the Golden Age and its exponents, and to encourage further reading, research – and enjoyment.

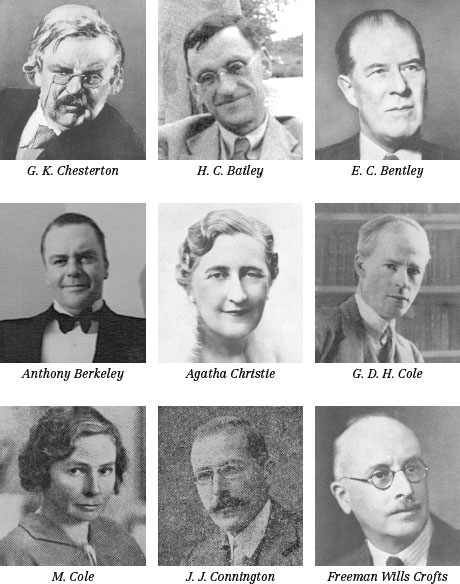

Members of the Detection Club elected 1930–49

1930

G. K. Chesterton 1874–1936

H. C. Bailey 1878–1961

E. C. Bentley 1875–1956

Anthony Berkeley 1893–1971

Agatha Christie 1890–1976

G. D. H. Cole 1889–1959

M. Cole 1893–1980

J. J. Connington 1880–1947

Freeman Wills Crofts 1879–1957

Clemence Dane 1887–1965

Robert Eustace 1871–1943

R. Austin Freeman 1862–1943

Lord Gorell 1884–1963

Edgar Jepson 1863–1938

Ianthe Jerrold 1898–1977

Milward Kennedy 1894–1968

Ronald A. Knox 1888–1957

A. E. W. Mason 1865–1948

A. A. Milne 1882–1956

Arthur Morrison 1863–1945

Baroness Orczy 1865–1947

Mrs Victor Rickard 1876–1963

John Rhode 1884–1965

Dorothy L. Sayers 1893–1957

Henry Wade 1887–1969

Victor L. Whitechurch 1868–1933

Helen Simpson (Associate Member) 1897–1940

Hugh Walpole (Associate Member) 1884–1941

1933

Anthony Gilbert 1899–1971

E. R. Punshon 1872–1956

Gladys Mitchell 1901–1983

1934

Margery Allingham 1904–66

1935

Norman Kendal 1880–1966

R. C. Woodthorpe 1886–1971

1936

John Dickson Carr 1906–77

1937

Nicholas Blake 1904–72

Newton Gayle (Muna Lee 1895–1965 and Maurice Guinness 1897–1991)

E. C. R. Lorac 1894–1958

Christopher Bush 1888–1973

1946

Cyril Hare 1900–58

Christianna Brand 1907–88

Richard Hull 1896–1973

Alice Campbell 1887–1976

1947

Val Gielgud 1900–81

Edmund Crispin 1921–78

1948

Dorothy Bowers 1902–48

1949

Michael Innes 1906–94

Michael Gilbert 1912–2006

Douglas G. Browne 1884–1963

Author Gallery

1

The Ritual in the Dark

On a summer evening in 1937, a group of men and women gathered in darkness to perform a macabre ritual. They had invited a special guest to witness their ceremony. She was visiting London from New Zealand and a thrill of excitement ran through her as the appointed time drew near. She loved drama, and at home she worked in the theatre. Now she felt as tense as when the curtain was about to rise. To be a guest at this dinner was a special honour. What would happen next she could not imagine.

Striking to look at, the New Zealander was almost six feet tall, with dark, close-set eyes. Elegant yet enigmatic, she exuded a quiet, natural charm that contrasted with her flamboyant dress sense and artistic taste for the exotic. Fond of wearing men’s clothes, smart slacks, a tie and a beret, this evening she had opted for feminine finery, her favourite fur wrap and extravagant costume jewellery. In common with her hosts, she had a passion for writing detective stories. Like them, she guarded her private life jealously.

Until tonight, she had only known these people from reading about them – and from reading their books. Many were household names, distinguished in politics, education, journalism, religion, and science, as well as literature. Most were British, a handful came from overseas. A young American was here, and so were the Australian granddaughter of a French marquis, and an elderly Hungarian countess who each year made a special journey for the occasion, travelling to England from her home in Monte Carlo.

The ritual was preceded by a lavish banquet in an opulent dining room. As the wine flowed, the visitor fought to conquer her nerves. Her escort, a discreet young Englishman, attentive and admiring, did his best to put her at ease. The food was superb, and the company convivial, but she preferred to let others talk rather than chatter herself. Sipping at her coffee, she half-listened to the speeches. At last came the moment she was waiting for. Everyone rose, and the party retired to another room. At the far end stood a large chair, almost like a throne. On the right side was a little table, and on the left, a lectern and a flagon of wine, its mouth covered with cloth.

All of a sudden, the lights went out, plunging the room into darkness. As if at a given signal, everyone else swept out through the door, leaving the woman from New Zealand and her companion alone. She became conscious of a faint chill in the air. Both of them were afraid to break the silence. As the moments ticked away, they dared to exchange a few words, speaking in whispers, as if in church.

Without warning, a door swung open. The Orator had arrived.

Resplendent in scarlet and black robes, and wearing pince-nez, a statuesque woman entered the room. She marched towards the lectern, holding a single taper to light the way. As she mounted the rostrum, the New Zealander saw that, in the folds of her gown, the Orator had secreted a side-arm. The visitor caught her breath. In the gloom, she could not identify the weapon. Was it a pistol, or a six-shooter?

Stern and purposeful, the Orator lit a candle. She gave no hint that she knew anyone was watching. At her command, a sombre procession of men and women in evening dress filed into the room. In the flickering candle-light, the visitor glimpsed unsmiling faces. Four members of the group carried flaming torches. Others clutched lethal weapons: a rope, a blunt instrument, a sword, and a phial of poison. A giant of a man brought up the rear. On the cushion that he carried, beneath a black cloth, squatted a grinning human skull.

The New Zealander was spellbound. The Orator cleared her throat and began to speak. She administered a lengthy oath to a burly man in his sixties. This secretive and elitist gathering had elected him to preside over their affairs, and he pledged to honour the rules of the game they played:

‘To do and detect all crimes by fair and reasonable means; to conceal no vital clues from the reader; to honour the King’s English … and to observe the oath of secrecy in all matters communicated to me within the brotherhood of the Club.’

As the ritual approached its end, the Orator lifted her revolver. Giving a faint smile, she fired a single shot. In the enclosed space, the noise was deafening. Her colleagues let out blood-curdling cries and waved their weapons in the air.

The eyes of the skull lit up the blackness, shining with a fierce red glow.

Stunned, the New Zealander found herself unable to speak. Her companion, familiar with the eccentric humour of crime writers, laughed like a hyena.

The visitor from New Zealand was Ngaio Marsh, who became one of her country’s most admired detective novelists, as well as a legendary theatre director. Her escort, Edmund Cork, was her literary agent, and he also represented Agatha Christie. The Orator who led the procession was Dorothy L. Sayers, and the bearer of the skull was another popular detective novelist, John Rhode. The satiric ritual followed a script so elaborate that Sayers, its author, thoughtfully supplied an explanatory diagram. The occasion was the installation of Edmund Clerihew Bentley as second President of the Detection Club.

Ngaio Marsh remembered that night for the rest of her life. Long after she returned home, she dined out on stories about what she had seen, embellishing details as time passed, and memory played tricks. In one account, she identified the setting for the ritual as Grosvenor House; in her biography, written in old age, she said it was the Dorchester. She also made conflicting claims about whether or not she met Agatha Christie that night. Detective novelists, like their characters, often make suspect witnesses and unreliable narrators.

Dorothy L. Sayers and John Rhode with Eric the Skull, photographed by Clarice Carr (by permission of Douglas G. Greene).

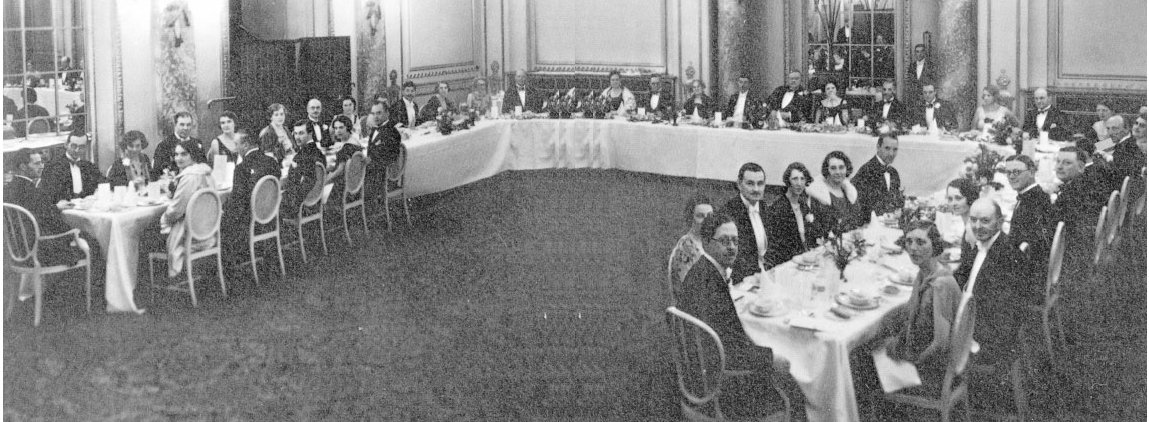

The Detection Club annual dinner, presided over by G.K. Chesterton.

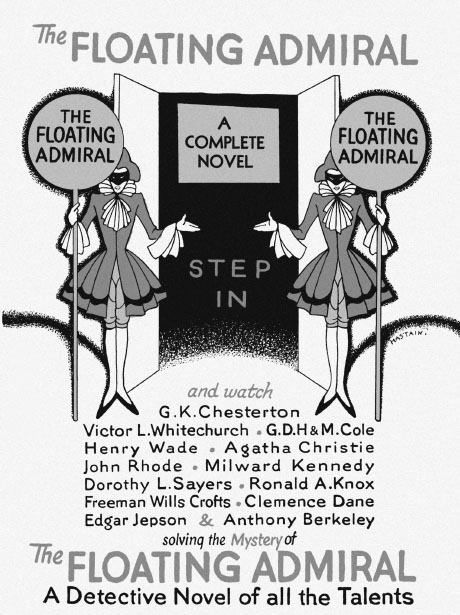

The Detection Club was an elite social network of writers whose work earned a reputation for literary excellence, and exerted a profound long-term influence on storytelling in fiction, film and television. Their impact continues to be felt, not only in Britain but throughout the world, in the twenty-first century. Yet a mere thirty-nine members were elected between the Club’s inception in 1930 and the end of the Second World War. The process of selecting suitable candidates for membership was rigorous, sometimes bizarrely so. The founders wanted to ensure that members had produced work of ‘admitted merit’ – a code for excluding the likes of ‘Sapper’ and Sydney Horler, whose thrillers starring Bulldog Drummond and Tiger Standish earned a huge readership, but were crude and jingoistic.