Полная версия

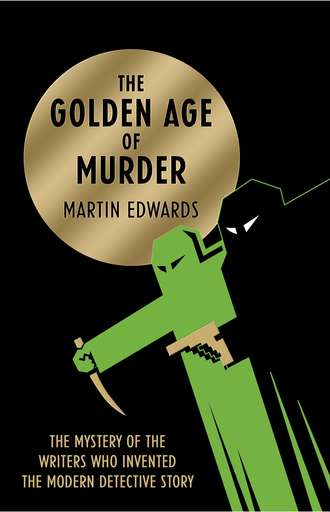

The Golden Age of Murder

Whelpton became involved with a married woman, and a chastened Sayers returned to London to lick her wounds. Her morale received a much-needed boost when – in the same post-war mood that saw women given the vote (provided they were thirty years old), the first female MP returned to office, and the first woman called to the Bar – Oxford University allowed women to graduate formally. Sayers was among the first group of female students from Oxford to be invested with both a B.A. and, because five years had passed since she had taken her finals, an M.A.

Equal rights for women remained, however, a distant dream. Working men worried about women taking their jobs, and trade union pressure pushed women towards the career cul-de-sac of domestic service. Even highly educated women found their horizons narrowing. Their choice was often between a career coupled with a life of celibacy, or redundancy and marriage.

With so many young men killed in combat, marriage was often not an option. The problem of the ‘surplus woman’ was widely debated by the chattering classes. One successful Golden Age suspense novel (written by a single woman) even saw a deranged serial killer decide to solve that problem by ridding the world of unmarried females. For Sayers, the answer lay in building an independent and fulfilling career, preferably as a writer. After being turned down for a series of jobs, she returned to teaching as a stopgap. Meanwhile, she tried her hand at a detective story.

She began with the mystery of ‘a fat lady found dead in her bath with nothing on but her pince-nez’. After the victim – a sympathetically presented Jew – underwent a sex change, this became the opening of Whose Body? In Sayers’ original version, Lord Peter Wimsey deduces that a body in a bath is not that of Sir Reuben Levy, a financier, because it is not circumcised. The publishers thought this too coarse for the delicate sensibilities of readers, and required her to change the physical evidence so as to suggest that the corpse belonged to a manual worker, rather than a rich man.

Originally, Wimsey featured as a minor character in an unpublished story. This was probably intended for the Sexton Blake series, produced by a writing syndicate. Sayers also toyed with the idea of introducing Wimsey in a play (‘a detective fantasia’ called The Mousehole) that she did not finish. When she embarked on a novel, she decided this son of a duke would be her detective.

Her intentions were satiric rather than snobbish. A detective who was not a professional police officer, she reasoned, needed to be rich and to have plenty of leisure time to devote to solving mysteries. She conceived Wimsey as a caricature of the gifted amateur sleuth, and found it amusing to soak herself in the lifestyle of someone for whom money was no object. When Wimsey first comes into the story, ‘his long amiable face looked as if it had generated spontaneously from his top hat, as white maggots breed from Gorgonzola.’

Sayers endowed Wimsey with criminology, bibliophily, music and cricket as favourite recreations. He is a Balliol man, equipped with a magnifying glass disguised as a monocle, a habit of literary quotation and an engaging, if often frivolous, demeanour. His valet and former batman, the imperturbable Mervyn Bunter, became devoted to him when they fought together during the war. Conveniently, his sister, Lady Mary, is to marry Detective Chief Inspector Charles Parker of Scotland Yard. Like many amateur sleuths, Wimsey benefits from keeping close to the police. The dialogue is flippant, but Wimsey’s worldview is darkened by his wartime experiences. He suffered shell-shock and had a nervous breakdown. When Parker is bothered by the idea of a corpse being shaved and manicured, Wimsey retorts, ‘Worse things happen in war.’

A distinctive amateur sleuth, a lively style and unorthodox storyline compensated for the fact that it is easy to guess whodunit. Sayers was always more interested in describing the culprit’s methods of carrying out and concealing the crime. In a nod to E. C. Bentley’s ground-breaking whodunit Trent’s Last Case, she had the killer refer to ‘that well-thought-out work of Mr. Bentley’s’. Later, it became a regular in-joke for Detection Club members to reference each other in their books.

Having fun with Wimsey offered relief from the depressing reality of life on a tight budget. The rent for her flat was seventy pounds a year, and she struggled to make ends meet. As she told her parents, in one of her innumerable frank and entertaining letters, writing about Wimsey ‘prevents me from wanting too badly the kind of life I do want, and see no chance of getting …’ If the novel did not sell, she intended to abandon her literary ambitions, and take up a permanent job as a teacher. But it was not what she wanted. When an American publisher offered to take Whose Body? she was overjoyed. Soon a British publisher accepted it as well.

While Sayers was working on her first novel, she began a relationship with someone very different from Whelpton, the writer John Cournos. Russian-born, Cournos came from a Jewish background, and his first language was Yiddish. His family emigrated to the United States when he was ten, but he moved to England and established a reputation as a novelist, poet and journalist. Cournos was disdainful about Sayers’ aristocratic detective, but she cheered up when Philip Guedella, a Jewish historian, asserted in the Daily News that ‘the detective story is the normal recreation of noble minds’.

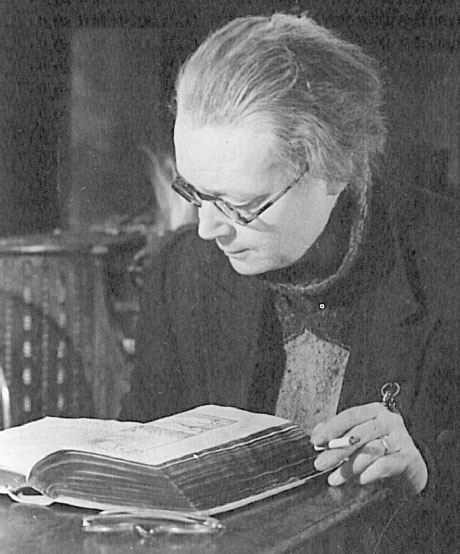

Dorothy L. Sayers and the mysterious Robert Eustace – photographed to publicise The Documents in the Case (by permission of the Marion E. Wade Center, Wheaton College, Wheaton, IL).

Dorothy L. Sayers (by permission of the Dorothy L. Sayers Society).

Cournos believed in free love, but Sayers, a High Anglican, was wary about sex outside marriage. Times were changing, and Marie Stopes, author of Married Love, had recently set up the country’s first clinic dispensing contraceptive products and advice – a crucial step towards making birth control socially acceptable. Sayers, however, had not yet overcome her objection to contraception as she did later with the Beast, Bill White. She did not want her relationship with Cournos to have the ‘taint of the rubber shop’.

This mismatch of expectations killed off their affair. She presented a fictionalized version of her emotional battle with Cournos eight years later, when she published Strong Poison. Harriet Vane, a detective novelist and Oxford graduate, is accused of murdering her selfish former lover Philip Boyes. She tells Wimsey that Boyes demanded her devotion, but ‘I didn’t like having matrimony offered as a bad-conduct prize’.

Cournos retaliated with a more intimate and brutal account of their relationship in The Devil is an English Gentleman. Stella, based on Sayers, resists Richard’s overtures, thinking: ‘If I give myself to him, he’ll forsake me.’ Meanwhile Richard ‘waited for the generous gesture, for a token of abandonment on her part; it did not come’. Cournos, who eventually emigrated to the USA, continued to publish books until the early Sixties. His destiny was to be remembered for his doomed romance with Sayers rather than for his own literary efforts.

Sayers started working for Benson’s shortly before Whose Body? was accepted. The job taught her how to use publicity to promote her writing, and the value of branding (before it was known as branding). Not from cussedness, but because she knew the value of a distinctive brand, she insisted on being known as Dorothy L. Sayers, not simply Dorothy Sayers. When her publisher, Ernest Benn, missed out her middle initial on the spine of one book a few years later, she was incandescent. After all, she said, people did not talk about E. Bentley, or G. Chesterton or G. Shaw.

Bill White was earthier than Cournos, and part of his appeal was that he did not share his predecessor’s lofty disdain for crossword puzzles and vulgar limericks. Thanks to him, Sayers experienced at last the sexual pleasure she craved. But once again, a man let her down. It was becoming a pattern in her life.

Sayers had never intended her affair with Bill White to be more than ‘an episode’. On returning to Benson’s, she worked furiously during the day, and then on her new book in the evenings. But the pretence of business as usual took a toll on her health. Her hair fell out, a visible symptom of severe emotional strain, and when it grew again, she decided her ‘little rat’s-tail plaits’ were hideous, and had her hair cut short and started wearing a silver wig.

She kept in touch with Cournos, but was deeply wounded when, having said he was not the marrying kind, he married Helen Kestner Satterthwaite, an American who wrote detective stories under the pen name of Sybil Norton. Biting back despair, Sayers wrote him a letter of congratulation, confiding that she had ‘gone over the rocks’, and that the result was John Anthony. Cournos’s reaction was anger that she had given herself to someone else, after refusing him. ‘Why not me?’ he demanded.

Sayers’ reply amounted to a scream of pain. ‘I have been so bitterly punished by God already, need you really dance on the body?’ The correspondence continued, as she agonized over what had gone wrong between them. One line explains a great deal about the way she led the rest of her life: ‘I am so terrified of emotion, now.’

That terror of emotion never left her. Sayers was devoted to her child, but in her own mind, she had committed ‘a bitter sin’. These were dark days, and she told Cournos, ‘It frightens me to be so unhappy.’ Although she had hoped things would improve, each day seemed worse than the last, and her work was suffering. She dared not even resort to suicide, ‘because what would poor Anthony do then?’ In Cournos’s novel, Stella threatens to kill herself, and Sayers did more than talk about self-harm in her correspondence: suicide forms a significant plot element in each of the first five Wimsey novels.

Yet there were lighter interludes. Cournos sent her an article by Chesterton about writing detective fiction, and she responded with a four-page critique. Game-playing mattered more to detective novelists at this point than the study of psychology, and she argued that characters in the detective story did not need to be drawn in depth. Clouds of Witness was most notable for a trial scene in the House of Lords where Peter Wimsey’s elder brother is accused of murder, a plot element she hoped would attract American readers.

Her next novel, Unnatural Death, displayed more interest in character, although the lesbianism of the heiress Mary Whittaker is implied rather than explicit. Thrifty as good novelists are, Sayers used a snippet of information from Bill White about an air-lock in a motorcycle feed pipe to provide a clue to the mystery. In a far from cosy passage, she describes how the arms of a corpse had been nibbled by rats. Years later, she explained to George Orwell (who had spoken of Wimsey’s ‘morbid interest’ in corpses) that in a detective novel, ‘where the writer has exerted himself to be extra gruesome, look out for the clue’. The frisson induced by the image of hungry rats was a ruse to distract readers from the possibility that the arm had been pricked by a hypodermic.

Wimsey is assisted by Miss Climpson and her undercover employment agency for single women. Climpson’s irrepressible verve was Sayers’ riposte to the likes of Charlotte Haldane, wife of the Marxist geneticist J. B. S. Haldane, who argued in Motherhood and its Enemies that a woman’s personal fulfilment depends on her inborn maternal instinct. Haldane is remembered as a feminist, but Sayers’ fiction was more sympathetic to single women, and her attitude towards them more progressive. Unnatural Death focused, as Sayers’ stories often did, more on the means by which death was caused than on whodunit; the culprit is obvious. The murder method involved injecting an air bubble into a vein. An ingenious idea, even if its feasibility was open to question.

She earned money by writing short stories, drawing on her own know-how for material. ‘The Problem of Uncle Meleager’s Will’ included a crossword puzzle clue, a nod to the fashionable craze which was also one of her own favourite pastimes. Motorcycling was an unlikely passion. She bought a ‘Ner-a-Car’ motorcycle, complete with sidecar, and rode it ‘in light skirmishing trim … with two packed saddle-bags and a coat tied on with string.’ ‘The Fantastic Horror of the Cat in the Bag’ features a race with a motorbike rejoicing in the improbable but factually accurate name of the Scott Flying-Squirrel.

The weirder realms of advertising presented her with the germ of ‘The Abominable History of the Man with Copper Fingers’, which is perhaps the best Wimsey short story. Sayers’ inspiration came from an American firm of morticians whose advertisements demanded: ‘Why lay your loved ones in the cold earth? Let us electroplate them for you in gold and silver.’

In April 1926, Sayers summoned up the nerve to drop a bombshell on her parents. She wrote a letter telling them, after a lengthy preamble including thanks for the present of an Easter egg, that she was ‘getting married on Tuesday (weather permitting) to a man named Fleming, who is at the moment Motoring Correspondent to the News of the World’. Hoping to soften the shock, she added, ‘I think you will rather like him.’ To her relief, they did.

The new man in her life, Oswald Arthur Fleming, was a divorced journalist twelve years her senior. She had only known him for a few months. A Scot hailing from the Orkneys, he liked to be known as ‘Mac’, though he wrote under the name Atherton Fleming. John Anthony, who knew Sayers as ‘Cousin Dorothy’, remained in Ivy Shrimpton’s care after the death of Ivy’s mother, and did not join the couple in their London flat.

Mac Fleming was a hard-living, hard-drinking newspaperman, keen on motor racing, and chronically hard up. He had two children by his first wife, but provided them with no financial support. He had written a book called How to See the Battlefields, based on his time as a war correspondent for the Daily Chronicle. For a time, he worked in advertising, which may explain how he and Sayers met.

She took to married life with gusto. She accompanied him to race meetings at Brooklands, and bought a motorcycle to ride herself, clad in goggles, gauntlets, and leather helmet. Motor racing was the latest craze, and leading drivers like Malcolm Campbell, Henry Segrave and J. G. Parry-Thomas – all of whom held the world land speed record in quick succession – were household names.

Racing offered thrills in abundance, but danger was ever present. The long, flat beach at Pendine Sands in Carmarthenshire was vaunted as ‘the finest natural speedway imaginable’, but while trying to regain the record, Parry-Thomas crashed his car. He was severely burned, and his head was ripped away from his neck by the drive chain. Mac, a friend of the dead man, was given the wretched task of reporting the horrific crash.

A less personally distressing project saw the News of the World pay for both Mac and Sayers to travel to France. Their task was to solve the murder of the English-born nurse May Daniels. Nurse Daniels had disappeared from a quayside waiting room when about to return to England after crossing the Channel with a friend for a day trip. Months later, her decomposed body, bearing signs of strangulation, was found by the roadside near Boulogne, and her gold wristwatch was missing. Clues (or red herrings) found near the body included a discarded hypodermic syringe, and an umbrella, while Nurse Daniels’ friend said she had spoken about a meeting with ‘Egyptian princes’.

Rumours spread that the dead woman was pregnant by a prominent member of the British establishment, and that the real purpose of her trip was to have an abortion performed by a mysterious Egyptian called Suliman. Questions were asked in Parliament about a baffling lack of cooperation between the British and French authorities, and the Press scented a cover-up. Mac and Sayers faced competition from other journalists, including former Chief Inspector Gough, hired as a ‘special investigator’ by the Daily Mail, and Netley Lucas, a conman turned crime correspondent for the Sunday News. None matched the brilliance of Lord Peter Wimsey, although Netley Lucas’ lifestyle was equally colourful: he later applied his talents to twin careers as a literary agent and a publisher before being sentenced to eighteen months with hard labour for fraud and plagiarism.

The Daniels puzzle remained unsolved. Despite this setback to her embryonic career as an amateur detective, Sayers became entranced by real-life mysteries, and introduced aspects of the Nurse Daniels case into Unnatural Death. After the excitement of the trip to France, Sayers fantasized about moving abroad, but this would have meant an even greater separation from John Anthony, and was out of the question. She hated the way that the Defence of the Realm Act – unaffectionately known as ‘Dora’ – curtailed individual liberties. In her eyes, the curbs on alcohol consumption, and restricted licensing hours, coupled with high levels of income tax, meant England was ‘no country for free men’.

She threw herself into work at Benson’s with renewed vigour. Colman’s of Norwich was a key client, and Sayers wrote The Recipe Book of the Mustard Club to promote Colman’s Mustard. Typically, she littered the text with quotations, and devised a frivolously elaborate history of the club, claiming it was founded by Aesculapius, god of medicine, and that Nebuchadnezzar was an early member. At first, the club was purely imaginary, featuring characters such as Lord Bacon of Cookham, and the club secretary Miss Di Gester, but the campaign was such a huge success that a real club was created. At its height, it boasted half a million members.

Sayers’ creative flair was ideally suited to marketing. She is credited with coining the phrase ‘it pays to advertise’, and collaborated on the most memorable advertisement of the time, part of a long campaign on behalf of Guinness stout. An artist called John Gilroy joined Benson’s in 1925, and he and Sayers became friends as well as colleagues. After a visit to the circus, Gilroy dreamed up the idea of using birds and animals to advertise Guinness. He sketched a pelican with a glass of Guinness on his beak, and Sayers suggested replacing that bird with a toucan. She wrote the lines:

If he can say as you can

Guinness is good for you,

How good to be a Toucan:

Just think what Toucan do.

To this day, there is a healthy market for Guinness toucan collectibles. Gilroy, a young man from Whitley Bay who had started out as a cartoonist, combined his advertising work with portrait painting, and Sayers was one of the first people to sit for him, sporting her silver wig. Gilroy was alive to her earthy physicality, and unexpected sex appeal, and rhapsodized about her: ‘terrific size – lovely fat fingers – lovely snub nose – lovely curly lips – a baby’s face in a way’.

Sayers was ready to spread her creative wings. She began to translate the Chanson de Roland into rhymed couplets, as well as a medieval poem, Tristan in Brittany. In addition, she dipped in and out of a projected book about Wilkie Collins. She never finished it, but her study of Collins’ methods influenced her own literary style. Her main focus remained on writing detective fiction. Spurred by the desire to support herself and her family, she became intensely productive. In 1928 alone she published three books, including a Wimsey novel, The Unpleasantness at the Bellona Club. The novel was reviewed by Dashiell Hammett, shortly before the former Pinkerton’s gumshoe established himself as a writer of hard-boiled private eye novels. Hammett’s writing, tastes, politics, and life experiences were a world away from Sayers’, but he felt her novel only missed being ‘a pretty good detective story’ because of a lack of pace: ‘Its developments come just a little too late to knock the reader off his chair.’

She had written enough short stories to publish a collection, Lord Peter Views the Body, under the new imprint of Victor Gollancz. A left-wing firebrand, Gollancz had rejected his orthodox Jewish upbringing and become a highly successful businessman with an unrivalled flair for marketing. As managing director of Sayers’ publishers, he revolutionized the advertising of fiction, with two-column splashes in the broadsheets which made his books seem important and exciting.

When he left Ernest Benn to set up on his own, Gollancz built a list of talented detective novelists, promoting newcomers like Milward Kennedy and Gladys Mitchell. But Sayers was much more bankable, and he begged her to join him. She admired Gollancz’s intelligence and drive, and trusted his judgement – it was Gollancz who recommended her to a new literary agent, David Higham. Author and publisher had starkly contrasting political and religious views, but they enjoyed each other’s company, and their mutual respect and loyalty was lifelong.

Since her next novel was under contract to Benn, Gollancz started with the short stories, and came up with a simple but striking yellow and black dust jacket. Gollancz, who was as desperate as his authors for his titles to be noticed (oddly, this is not a trait which all writers associate with their publishers), honed this technique to perfection in the next few years. The bold, yellow jackets, with typography in varying sizes and typefaces, were as recognizable as advertising posters – and Gollancz duly hired Edward McKnight Kauffer, an American modernist whose posters for the London Underground were much admired, to produce eye-catching abstract artwork for works of detective fiction.

Gollancz claimed to have invented the term ‘omnibus volume’; long before the era of the fat airport thriller, he was convinced that readers liked bulky books, which yielded good profits. He had an idea for a huge anthology of mystery stories, and persuaded Sayers to edit it. With his encouragement, she researched the history of the detective story in the course of compiling a weighty gathering of genre fiction. She was probably influenced by Wright and Wrong – that is, by comparable projects undertaken in the United States by Willard Huntington Wright (better known as detective novelist S. S. Van Dine) and in Britain by E. M. Wrong. Her lengthy essay introducing the first series of Great Short Stories of Detection, Mystery and Horror showed the breadth of her reading and her critical insight.

As Sayers’ reputation blossomed, the intense happiness of the early days of marriage faded. Pressure of work, and personal circumstances, took their toll. During the war, Mac had been gassed, two of his brothers had died and another was badly injured. His previous wife reckoned that this sequence of personal disasters transformed his personality, and not in a good way. Now Mac was afflicted by a series of health problems, and owed money to the taxman. When he had to give up his job and go freelance, his morale – and temper – suffered. Once again Sayers found herself let down by a man. Her reaction was to feast on comfort food and to drink more than was good for her.

Despairing of her ‘rapidly fattening frame’, she had her hair cut in an Eton crop, a severe, boyish style that had recently supplanted the ‘bob’. Her choice of clothes became even more outlandish, and on one occasion she turned up to a public function in a man’s rugby shirt. Her plain appearance and fondness for masculine dress led some people to assume she was a lesbian. But with detective novelists, as with detective novels, it is a mistake to judge a book by its cover.