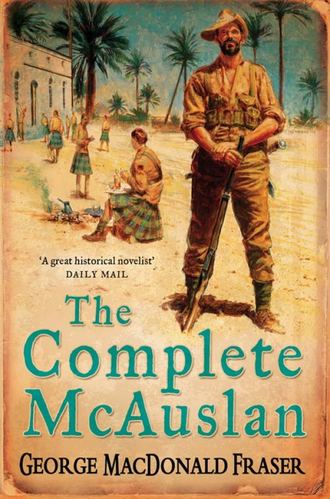

Полная версия

The Complete McAuslan

Your real hero can sleep through an elephant stampede, but wakes at the sound of a cat’s footfall. I can sleep through both. But the shriek of ancient brakes as a train grinds violently to a halt wakes me. I came upright off the seat like a bleary panther, groping for my gun, knowing that something was wrong and trying to think straight in a second. We shouldn’t be stopping before Jerusalem; one glance through the window showed only a low, scrubby embankment in moon-shadow. As the wheels screamed to a halt I dived into the corridor, ears cocked for the first shot. We were still on the rails, but my mind was painting vivid pictures of a blocked line and an embankment stiff with sharpshooters.

I went through the door to the platform behind the tender; in the cabin I could see the driver, peering ahead over the side of his cab.

“What the hell is it?” I shouted.

He shouted back in Arabic, and pointed ahead.

Someone was running from the back of the train. As I dropped from the platform to the ground he passed through the shaft of light between two coaches and I recognised Black’s balmoral. He had his Luger out.

He slowed down beside me, and we went cautiously up past the engine, with the little wisps of steam curling up round us. The driver had his spotlight on, and the long shaft lit up the line, a tunnel of light between the embankment walls. But there was nothing to see; the embankment itself was dead still. I was turning to ask the driver what was up when he gave an excited little yelp behind us. Far down the track, on the edge of the spotlight beam, a red light winked and died. Then it winked again, and died.

A hoarse voice said: “Get two men with rifles to the top of the bank, either side. Keep everyone else on the train. Then come back here.”

It had almost finished speaking before I realised it was my own voice. Black faded away, and a moment or two later was back.

“They’re posted,” he said.

I wiped my sweaty hand on my shirt and took a fresh grip of the revolver which I ought to have remembered back in Cairo, so that some other mug could have been here, playing cops and robbers with Bert Stern or whoever it was. “Let’s go,” I said, just like Alan Ladd if he was a soprano. My hoarse voice had deserted me.

We walked up the line, our feet thumping on the sleepers, the spotlight behind us throwing our shadows far ahead, huge grotesques on the sand. The line “The dust of the desert is sodden red” came into my head, but I hadn’t had time even to think the uncomfortable thought about it when he just materialised in front of us on the track, so suddenly that I was within an ace of letting fly at him. I know I gasped aloud in surprise; Black dropped on one knee, his Luger up.

“Hold it!” It was my hoarse voice again, sounding loud and nasty. And with the fatal gift of cliché that one invariably displays in such moments, I added, “Don’t move or I’ll drill you!”

He was a young man, in blue dungarees, hatchet-faced, Jewish rather than Arab. His hands were up; they were empty.

“Pliz,” he said. “Friend. Pliz, friend.”

“Cover him,” I said to Black, which was dam’ silly, since he wasn’t liable to be doing anything else. Keeping out of line, I went closer to him. “Who are you?”

“Pliz,” he said again. He was one of these good-looking, black-curled Jews; his mouth hung open a bit. “Pliz, line brok’.” And he pointed ahead up the track.

I left Black with him, collected the driver and his mate, and went off up the track. Sure enough, after a little search we found a fish-plate unscrewed and an iron stake driven between the rail ends—enough to put us off the track for sure. I didn’t quite realise what that signified until the driver broke into a spate of Arabic, gesturing round him. I looked, and saw we were out of the cutting; now the ground fell away from the track on both sides, a rock-strewn slide that we would have crashed down.

While the driver and his mate banged out the stake and got to work on the fishplate, I went back to where Black had the young Jew in the lee of the engine. There was a small crowd round them, contrary to my orders, but one of them—an Arab Legion officer—was talking to him in Hebrew, and getting results.

“What’s he say?” I asked.

“Oh, God, he’s a dope,” said the officer. “He found the rail broken, I think, and heard the train coming. So he stopped us.”

“He found the rail broken? In the middle of the bloody night? What was he doing here?”

“He doesn’t seem to know.” He directed a stream of Hebrew at the youth and got one back, rather slower. The voice was thick, soft.

“Don’t believe a word of it,” a voice was beginning, but I said, “Shut up,” and asked the officer to translate.

“He was looking for a goat. He lives in a village somewhere round here.” It sounded vaguely biblical; what was the story again … the parable of the shepherd …

“What about the red light?” It was Sergeant Black.

Questioned, the youth pulled from his pocket a lighter and a piece of red cellophane.

“For God’s sake,” I said.

“He’s probably a bloody terrorist,” said someone.

“Don’t be a fool,” I said. “Would he warn us if he was?”

“How dare you call me a fool?” I realised it was my old friend the pouchy half-colonel. “Who the—”

“Button your lip,” I said, and I thought he would burst. “Who authorised you to leave the train? Sergeant Black, I thought I gave orders?”

“You did, sir.” Just that.

“Then get these people back on the train—now.”

“Now, look here, you.” The half-colonel was mottling. “I’ll attend to you in due course, I promise you. Sergeant, I’m the senior officer: take this man”—he indicated the Jew—“and confine him in the guard’s van. It’s my opinion he’s a terrorist …”

“Oh, for heavens’ sake,” I said.

“… and we’ll find out when we get to Jerusalem. And you,” he said to me, “will answer for your infernal impudence.”

It would have been a great exit line, if Sergeant Black had done anything except just stand there. He just waited a moment, staring at the ground, and then looked at me.

“O.C. train, sir?” he said.

I didn’t catch on for a moment. Then I said, “Carry on, sergeant. Take him aboard. Get the others aboard, too—except those who want to stand around all night shooting off their mouths in a soldier-like manner.” What had I got to lose?

I went up the track, to where the driver was gabbling away and yanking fiercely on a huge spanner. He gave me a great grin and a torrent of Arabic, from which I gathered he was coming on fine.

I went back to the train: Sergeant Black was whistling in the sentries from the banks; everyone was aboard. Presently the driver and his mate appeared, chattering triumphantly, and as I climbed aboard the engine crunched into life and we lumbered up track. The whole incident had occupied about ten minutes.

In the guard’s van Black and the Arab Legion captain and my half-colonel were round the prisoner—that’s what he was, no question. The captain interrogated him some more, and the half-colonel announced there was no doubt about it, the damned Yid was a terrorist. To the captain’s observation that he was an odd terrorist, warning trains instead of wrecking them, he paid no heed.

“I hold you responsible, sergeant,” he told Black. “He must be handed over to the military police in Jerusalem for questioning, and, I imagine, subsequent trial and sentence. You will …”

“You won’t hold my sergeant responsible,” I said. “I’ll do that. I’m still in command of this train.”

For a moment I thought he was going to hit me, but unfortunately he didn’t. He just bottled his apoplexy and marched out, and the captain went with him, leaving me and Black and the Jew. The two deserters, I supposed, were farther up the train. We were rattling along at full clip now; Black reckoned we were maybe two hours out of Jerusalem. I gave him a cigarette, and nodded him over to the window.

“Well?” I said. “What d’you make of him?”

He took off his bonnet and shook his cropped head.

“He’s no terrorist, for certain,” I said. “Well, ask yourself, is he?”

“I wouldnae know. He looks the part.”

“Oh, come off it, sergeant. He warned us.”

“Aye.” He dragged on the cigarette. “What was he doin’ there, in the middle of the night?”

“Looking for a goat.”

“In dungarees stinkin’ o’ petrol. Aye, well. And makin’ signals wi’ a lighter an’ cellophane. Yon’s a right commando trick for a farmer. That yin’s been a sodger, you bet. Probably wi’ us, in Syria, in the war.”

“But he doesn’t speak English.”

“He lets on he disnae.” He smiled. “And if you’re lookin’ for goats, ye don’t go crawling aboot on yer belly keekin’ at fish-plates, do ye?”

“You think he knew, before, about the broken rail?”

“I’m damned sure of it, sir. Yon was a nice, professional job. He knew aboot it, but why he tellt us … search me.”

I looked over at the Jew. He was sitting with his head in his hands.

“He told us, anyway,” I said. “Whether he’s a terrorist or not, or knows terrorists, doesn’t much matter.”

“It’ll matter tae the military police in Jerusalem. Maybe they’ve got tabs on him.”

“But, dammit, if he is a Stern Gangster, why the hell would he stop the train?”

Black ground out his cigarette and looked me in the face. “Maybe he’s just soft-hearted. Maybe he doesnae want tae kill folk after all.”

“Who are you kidding? You believe that?”

“Look, sir, how the hell dae I know? Maybe he’s a bloody Boy Scout daein’ his good deed. Maybe he’s no’ a’ there.”

“Yes,” I said. “Maybe.” It was difficult to see any rational explanation. “Anyway, all we have to do is see that he gets to Jerusalem. Then he’s off our backs.”

“That’s right.”

I hesitated about telling Black to keep a close eye on him, and decided it was superfluous. Then I went back up the train, full of care, noticing vaguely that the two deserters were in a group playing rummy, and that the blinds were down on the padre’s compartment. Captain and Mrs Garnett had their door open, and were talking animatedly; in the background one of the twins was whimpering quietly.

“But, darling,” he was saying. “German measles isn’t serious. In fact, it’s a good thing if they get it when they’re little.”

“Who says?”

“Oh, medical people. It’s serious if you get it when you’re older, if you’re a girl and you’re pregnant. I read that in Reader’s Digest.”

“Well, who’s to say it’s true? Anyway, I’m worried about Angie now, not … not twenty years hence. She may never get married, anyway, poor little beetle.”

“But it may not be German measles, anyway, darling. It may be nappy rash or something …”

Everybody had their troubles, including the formerly incarcerated Arab legionnaire, who was now trying to get into the lavatory, and wrestling with the door handle. The young pilot officer was lending a hand, and saying, “Tell you what, Abdul, let’s try saying ‘Open Sesame’ …”

All was well with the A.T.S., the Australians, and the airmen; the excitement caused by our halt had quieted down, and I closed my compartment door hoping nothing more would happen before we got to Jerusalem. How much trouble could the pouchy half-colonel make, I wondered. The hell with him, I had been within my rights. Was the young Jew a terrorist, and if he was, why had he stopped the train? And so on, and I must have been dozing, for I remember being just conscious of the fact that the rhythm of the wheels had changed, and we were slowing, apparently to take a slight incline, and I was turning over on the seat, when the shot sounded.

It was a light-calibre pistol, by the sharp, high crack. As I erupted into the corridor it came again, and then again, from the back of the train. An A.T.S. shrieked, and there were oaths and exclamations, and I burst into the guard’s van to find Sergeant Black at the window, his Luger in his hand, and the smell of burned cordite in the air. The train was picking up speed again at the top of the incline. The Jew was gone.

“What the hell …” I was beginning, and stopped. “Are you all right?”

He was standing oddly still, looking out at the desert going by. Then he holstered his gun, and turned towards me.

“Aye, I’m fine. I’m afraid he got away.”

“The Jew? What happened?”

“He jumped for it. When we slowed down to take the hill. Went out o’ that windae like a hot rivet, and doon the bank. I took a crack at him, two or three shots …”

“Did you hit him?”

“Not a chance.” He said it definitely. “It’s no use shootin’ in this light.”

There were people surging at my back, and I wheeled round on them.

“Get back to your carriages, all of you! There’s nothing to get alarmed about.”

“But the shooting …” “What the hell …”

“There’s nothing to it,” I said. “A prisoner jumped the train, and the sergeant took a pot at him. He got away. Now, go back to your compartments and forget it. We’ll be in Jerusalem shortly.”

Through the confusion came Old Inevitable himself, the pouchy half-colonel, demanding to know what had happened. I told him, while the others faded down the corridor, and he wheeled to the drawling major, who was at his elbow, and bawled:

“Stop the train!”

“Now, take it easy,” I said. “There’s no point in stopping; he’s over the hills and far away by now, and he’s a lot less important than the safety of this train. We’re not stopping until we get to Jerusalem.”

“I’ll decide that!” he snapped, and he had an ugly, triumphant look as he said it. “You’ve lost the prisoner, in spite of my instructions, and this train is being stopped …”

“Not while I command it.”

“You don’t! You’re a complete bloody flop! I’m taking over. John, pull that communication …”

It must have been pure chance, but when the major turned uncertainly to touch the communication cord, Sergeant Black was right in his way. There was one of those pregnant silences, and I jumped into it.

“Now look, sir,” I said to the half-colonel. “You’re forgetting a few things. One, I am O.C. train, and anyone who tries to alter that answers to a general court-martial. Two, I intend to report you to the G.O.C. for your wilful hampering of my conduct of this train, and your deliberate disobedience of orders from properly constituted authority.”

“Damn you!” he shouted, going purple.

“You left the train when we halted, in flat defiance of my instructions. Three, sir, I’ve had about my bellyful of you, sir, and if you do not, at once, return to your compartment, I’m going to put you under close arrest. Sir.”

He stood glaring and heaving. “Right,” he said, at last. He was probably wondering whether he should try, physically, to take over. He decided against it. “Right,” he said again, and he had his voice under control. “Major Dawlish, you have overheard what has been said here? Sergeant, you are a witness …”

“Aye, sir,” said Black. “I am that.”

“What do you mean?” snapped the half-colonel, catching Black’s tone. “Let me tell you, Sergeant, you’re in a pretty mess yourself. A prisoner in your …”

“Not a prisoner,” I said. “A man who had warned us about the railway line and was being carried on to Jerusalem, possibly for interrogation.

He looked from me to Black and back again. “I don’t know what all this is about,” he said, “but there’s something dam’ fishy here. You,” he said to me viciously, “are going to get broken for this, and you, Sergeant, are going to have a great deal of explaining to do.” He wheeled on his buddy. “Come along, John.” And they stumped off down the corridor.

When they had gone I lit a cigarette. I was shaking. I gave another one to Black, and he lit up, too, and I sat down on a box and rested my head on my hand.

“Look,” I said. “I don’t understand it either. But there is something dam’ fishy, isn’t there? How the hell did he get away?”

“I told ye, sir. He jumped.”

“Oh, yes, I know. But look, Sergeant, let’s not fool around. Between ourselves, I’m not Wild Bill Bloody Hickock, but he couldn’t have broken from me, so I’m damned sure he couldn’t break from you. People as experienced as you, I mean, you carry a Luger, you know?”

He said, poker-faced, “I must have dozed off.”

I just looked at him. “You’re a liar,” I said. “You never dozed off in your life—except when you wanted to.”

His head came up at that, and he sat with smoke trickling up from his tight mouth into his nostrils. But he didn’t say anything.

“What are we going to tell them in Jerusalem?” I said.

“Just what I told you, sir. He was a gey fast mover.”

“You could get busted,” I said. “Me, too. Oh, it’ll be well down my crime-sheet, after tonight. I’ve done everything already. But it could be sticky down at your end too.”

He smiled. “My number’s up in the next couple of months. I’ve got a clean sheet. I’m no’ worried about being busted.”

He seemed quite confident of that. He looked so damned composed, and satisfied somehow, that I wondered if perhaps the exigencies of the journey had unhinged me a little.

“Sergeant Black,” I said. “Look here. The man was a terrorist—you think so, anyway. Well, why on earth …”

“Yes, sir?”

“Never mind,” I said wearily. “The hell with it.”

I knew what he was going to come back to. Terrorist or not, he had saved the train, and everyone on it, me and the pouchy half-colonel and Angie and Petey and the A.T.S. and lavatory-locked legionnaires. Why, God alone knew. Maybe he hadn’t meant to, or something. But I knew Black and I were speculating the same way, and giving him the benefit of the doubt, and thinking of what would have happened if he had been a terrorist, and there had been tabs on him in Jerusalem.

“The hell with it,” I said again. “Sergeant, I’m out of fags. You got one?”

It was while I was lighting up and looking out at the desert with the ghostly shimmer that is the Mediterranean dawn beginning to touch its dark edges, that for no reason at all I remembered Granny’s story about the cattle-train at Tyndrum. I suppose it was the association of ideas: people jumping from trains. I told Sergeant Black about it, and we discussed grannies and railways and related subjects, while the train rattled on towards Jerusalem.

Just before we began to run into the suburbs, the white buildings perched on the dun hillsides, Sergeant Black changed the topic of conversation.

“I wouldn’t worry too much about yon half-colonel,” he said.

“I’m not worried,” I said. “You couldn’t call it worry. I’ve just got mental paralysis about him.”

“He might think twice about pushing charges against you,” said Black. “Mind you, he stepped over the mark himsel’. He wouldnae come well out of a court-martial. And ye were quite patient wi’ him, all things considered.” He grinned. “Your granny wouldnae have been as patient.”

“Huh. Wonder what my granny would have said if she had been wheeled before the brigadier?”

“Your granny would have been the brigadier,” he said. “We’re here, sir.”

Jerusalem station was an even bigger chaos than Cairo had been; there were redcaps everywhere, and armed Palestine Police, and tannoys blaring, and people milling about the platforms. Troop Train 42 disgorged its occupants: I didn’t see the half-colonel go, but I saw the Arab Legion forming up to be inspected, and Captain Garnett and his wife, laden with heaps of small clothes and handbags from which bottles and rolls of cotton wool protruded, carrying Angie and Petey in a double basket; and the A.T.S. giggling and walking arm-in-arm with the Aussies and the R.A.F. types, and the padre with loads of kit, bargaining with a cross-eyed thug wearing a porter’s badge. Sergeant Black strode through the train, seeing everyone was off; then he snapped me a salute and said:

“Permission to fall out, sir?”

“Carry on, Sergeant,” I said.

He stamped his feet and hoisted his kit-bag on to his shoulder. I watched him disappear into the crowd, the red hackle on his bonnet bobbing above the sea of heads.

I went to the R.T.O.’s office, and sank into a chair.

“Thank God that’s over,” I said. “Where do I go from here? And I hope it’s bed.”

The R.T.O. was a grizzled citizen with troubles. “You MacNeill?” he said. “Troop Train 42?”

“That’s me,” I said, and thought, here it comes. Pouchy had probably done his stuff already, and I would be requested to report to the nearest transit camp and wait under open arrest until they were ready to nail me for—let’s see—insubordination, permitting a prisoner to escape, countenancing illegal trafficking in currency, threatening a superior, conduct unbecoming an officer in that I had upbraided a clergyman, and no doubt a few other assorted offences that I had overlooked. One way and another I seemed to have worked my way through a good deal of the prohibitions of the Army Act: about the only one I could think of that I hadn’t committed was “unnatural conduct of a cruel kind, in that he threw a cat against a wall”. Not that that was much consolation.

“MacNeill,” muttered the R.T.O., heaving his papers about. “Yerss, here it is. Got your train documents?” I gave them to him. “Right,” he said. “Get hold of this lot.” And he shoved another pile at me. “Troop Train 51, leaves oh-eight-thirty for Cairo. You’ll just have time to get some breakfast.”

“You’re kidding,” I said.

“Don’t you believe it, boy,” he said. “Corporal Clark! Put these on the wire, will you? And see if there’s any word on 44, from Damascus. Dear God,” he rubbed his face. “Well, what are you waiting for?”

“You can’t put me on another train,” I said. “I mean, they’ll be wanting me for court-martial or something.” And I gave him a very brief breakdown.

“For God’s sake,” he said. “You were cheeky to a half-colonel! Well, you insubordinate thing, you. It’ll have to keep, that’s all. You weren’t the only one who was getting uppish last night, you know. Some people gunned up a convoy near Nazareth, and apart from killing half a dozen of us they did for a United Nations bigwig as well. So there’s activity today, d’you see? Among other things, there aren’t enough perishing subalterns to put in charge of troop trains. Now, get the hell out of here, and get on that train!”

I got, and made my way to the buffet, slightly elated at the idea of making good my escape on the 8.30. Not that it would do any good in the long run; the Army always catches up, and the half-colonel was the vindictive sort who would have me hung up if it took him six months. In the meantime I wasn’t going to see much of the famous old city of Jerusalem; eating my scrambled eggs I wondered idly if some Roman centurion had once arrived here after a long trek by camel train, only to be told that he was taking the next caravan out because everyone was all steamed up and busy over the arrest of a preaching carpenter who had been causing trouble. It seemed very likely. If you ever get on the fringe of great events, which have a place in history, you can be sure history will soon lose it as far as you are concerned.

I got the 8.30, and there was hardly a civilian on it; just troops who behaved themselves admirably except at Gaza, where there was the usual race in the direction of Ahmed’s back street banking and trust corporation; I just pretended it wasn’t happening; you can’t fight international liquidity. And then it was Cairo again, just sixteen hours since I had left it, and I dropped my papers with the R.T.O., touched my revolver butt for the hundred and seventeenth time to make sure I still had it, and went back to the transit camp, tired and dirty. I went to sleep wondering where the escaping Jew had got to by this time, and why Sergeant Black had let him go. It occurred to me that the Jew might have had a pretty rough time in Jerusalem, what with everyone’s nerves even more on edge with the Nazareth business. Anyway, I wasn’t sorry he had got away; all’s well that ends well; I slept like a log.

All hadn’t ended well, of course; two mornings later a court of inquiry was convened in an empty barrack-room at the transit camp, to examine the backsliding and evil behaviour of Lieutenant MacNeill, D., and report thereon. It consisted of a ravaged-looking wing-commander as president, an artillery major, a clerk, about a dozen witnesses, and me, walking between with the gyves (metaphorically) upon my wrists. The redcap at the door tried to keep me out because I didn’t have some pass or other, but on finding that I was the star attraction he ushered me to a lonely chair out front, and everyone glared at me.