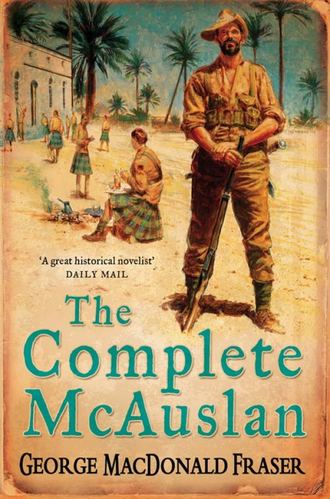

Полная версия

The Complete McAuslan

They strip a man’s soul bare, those courts of inquiry. With deft, merciless questioning they had found out in the first half hour not only who I was, but my rank and number; an officer from the transit camp deponed that I had been resident there for several days; yet another certified that I had been due out on such-and-such a flight; an airport official confirmed that this was true, and then they played their mastercard. The pilot of the aircraft (this is sober truth) produced an affidavit from his co-pilot (who was unable to attend because of prickly heat) that I had not, to anyone’s knowledge, boarded the plane, and that my seat had been given to Captain Abraham Phillipowski of the Polish Engineers, attached to No. 117 Field Battery, Ismailia.

They were briefly sidetracked because the president plainly didn’t believe there was such a person as Captain Abraham Phillipowski, but once this had been established to their satisfaction the mills of military justice ground on, and another officer from the transit camp described graphically my return after missing the plane, and my despatch to Jerusalem.

The president wanted to know why I had been sent to Jerusalem; witness replied that they had wanted to keep me employed pending a court of inquiry into why I had missed my plane; the president said, pending this court, you mean; witness said yes, and the president said it seemed bloody silly to him sending a man to Jerusalem in between. Witness said huffily it was no concern of his, the president said not to panic, old boy, he had only been making a comment, and witness said all very well, but he didn’t want it appearing in the record that he had been responsible for sending people to Jerusalem when he hadn’t.

The president suggested to the clerk that any such exchange be deleted from the record (which was assuming the proportions of the Greater London telephone directory, the way the clerk was performing with his shorthand), and I unfortunately coughed at that moment, which was taken as a protest. A judicial huddle ensued, and the president emerged, casting doubtful glances at me, to ask if I had anything to say.

“I forgot my gun,” I said.

He seemed disappointed. “He forgot his gun,” he repeated to the clerk.

“I heard,” said the clerk.

“All right, all right!” cried the president. “Keep your hair on.” He looked at me. “Anything else?”

“Should there be?” I asked. It seemed to me that they hadn’t really started yet, but I wasn’t volunteering information about events on the train, which seemed to me to dwarf such trivia as my missing my plane in the first place.

“Dunno,” said the president. He turned to the clerk. “How do we stand, old boy?”

“He forgot his gun, he missed the plane,” said the clerk bitterly. “That’s what we’re here to establish. What more do you want?”

“Search me,” said the president. “You did miss the plane, didn’t you?” he asked me.

“That’s irregular,” bawled the clerk. “At least, I think it is. You’re asking him to convict himself.”

“Rot,” said the president. “He hasn’t been charged, has he? Anyway, old boy, you’re mixing it up with wives not being able to testify against their husbands.”

“I need a drink,” said the clerk.

“Good show,” said the president. “Let’s adjourn, and then you can type all this muck out and we’ll all sign it. Any objections, objection overruled. Smashing.”

The proceedings of that court occupied about forty-five minutes, and heaven knows how many sheets of foolscap, but it did establish what it had set out to do—that I had negligently failed to take a seat on an aircraft. It was all carefully forwarded to my unit, marked attention Commanding Officer, and he blew his stack, mildly, and gave me three days’ orderly officer for irresponsible idiocy—not so much for missing the aircraft as for causing him to waste time reading the report. But of Black, and the escaping Jew, and threats, and insubordination, and currency offences there was never a word.

And, as my grandmother would have said, that is what happened on the Cairo—Jerusalem railway.

The Whisky and the Music

The ignorant or unwary, if asked whether they would rather be the guests of an officers’ mess or a sergeants’, would probably choose the officers’. They might be motivated by snobbery, but probably also by the notion that the standards of cuisine, comfort, and general atmosphere would be higher. They would be dead wrong.

You will get a bit of the old haut monde from the officers in most units, although in a Highland regiment the native savagery has a tendency to show through. I remember the occasion when two Guards officers, guests of our mess, were having a delicate Sunday morning breakfast and discussing Mayfair and the Season with the Adjutant, himself an exquisite, when there entered the motor transport officer, one Elliot, a hard man from the Borders. Elliot surveyed the table and then roared:

“Naethin’ but toast again, bigod! You,” he shouted at the Adjutant, “ye bloody auld vulture, you, ye’ve been gobblin’ my plain bread!” And he wrenched the Adjutant’s shirt-front out of his kilt, slapped him resoundingly on the solar plexus, and ruffled his hair. This was Elliot’s way of saying good morning, but it upset the Guards. They just looked at each other silently, like two Jack Bennys, and then got slowly to their feet and went out, looking rather pale.

That would never happen in a sergeants’ mess. Sergeants are too responsible. They tend to be young-middle-aged soldiers, with a sense of form and dignity; among officers there is always the clash of youth and age, but with sergeants you have a disciplined, united front. And whereas the provisioning and amenities of an officers’ mess are usually in the hands of a president who has had the job forced on him and isn’t much good at it, your sergeants look after their creature comforts with an expertise born of long service in hard times. Wherever you are, whoever goes short, it won’t be the sergeants; they’ve been at the game too long.

Hogmanay apart, officers never saw inside our sergeants’ mess (“living like pigs as we do,” said the Colonel, “it would make us jealous”), so when Sergeant Cuddy of the signals section invited me in for a drink I accepted like a shot. We had been out in the desert on an exercise, and Cuddy and I had spent long hours on top of a sand-hill with a wireless set, watching the company toiling over the sun-baked plain below, popping off blanks at each other. Cuddy was a very quiet old soldier with silver hair; his first experience of signals had been with flags and pigeons on the Western Front in the old war, and I managed to get him to talk about it a little. It emerged that he had heard of, although he had not known, my great-uncle, who had been a sergeant with the battalion at the turn of the century.

“There’ll be a picture of him in the mess,” said Cuddy. And then, after a long pause, he added: “Perhaps ye’d care to come in and see it, when we go back to barracks?”

“Will it be all right?” I asked, for regimental protocol is sometimes a tricky thing.

“My guest,” said Cuddy, so I thanked him, and when we had packed up the exercise that afternoon I accompanied him up the broad steps of the whitewashed building just outside the barracks where the sergeants dwelt in fortified seclusion.

In the ante-room there was only the pipe-sergeant, perched in state at one end of the bar, and keeping a bright eye on the mess waiters to see that they kept their thumbs out of the glasses.

“Guest. Mr MacNeill,” announced Cuddy, and the pipey hopped off his stool and took over.

“Come away ben, Mr MacNeill,” he cried. “Isn’t this the pleasure? You’ll take a little of the creature? Of course, of course. Barman, where are you? Stand to your kit.”

I surveyed the various brands of “the creature” on view behind the bar, and decided that the Colonel was right. You would never have seen the like in an officers” mess. There was the Talisker and Laphroaig and Islay Mist and Glenfiddich and Smith’s Ten-year-old—every Scotch whisky under the sun. How they managed it, in those arid post-war years, I didn’t like to think.

I’m not a whisky man, but asking for a beer would have been unthinkable; I eventually selected an Antiquary, and the pipe-sergeant raised his brows and pursed his lips approvingly.

“An Edinburgh whisky,” he observed judicially. “Very light, very smooth. I’m a Grouse man, myself.” He watched jealously as the barman poured out the very pale Antiquary and gave me my water in a separate glass (if you want to be a really snob whisky drinker, that is the way you take it, in alternate sips, a right “professional Highlander” trick). Then we drank, the three of us, and the pipe-sergeant discoursed on whisky in general—the single malts and the blends, and “the Irish heresies”, and strange American concoctions of which he affected to have heard, called “Burboon”.

Sergeant Cuddy eventually interrupted to say that I had come to view the group photographs lining the mess walls, to see my great-uncle, and the pipe-sergeant exclaimed in admiration.

“And he was in the regiment? God save us, isn’t that the thing?” He bounded from his stool and skipped over to the row of pictures, some of them new and grainy-grey, others deepening into yellow obscurity. “About when would that be, sir? The ’nineties? In India? Well, well, let’s see. There’s the ’02, but that was in Malta, whatever they were doing there. Let’s see—Ross, Chalmers, Robertson, McGregor—all the teuchters, and look at the state of them, with their bellies hanging over their sporrans. I’d like to put them through a foursome, wouldn’t I just.” He went along the row, Cuddy and I following, calling out names and bestowing comments.

“South Africa, and all in khaki aprons. My, Cuddy, observe the whiskers. Hamilton, Fraser, Yellowlees, O’Toole—and what was he doing there, d’ye suppose? A right fugitive from the Devil’s Own, see the bog-Irish face of him. Murray, Johnstone—”

“I mind Johnstone, in my time,” said Cuddy. “Killed at Passchendaele.”

“—Scott, Allison—that’ll be Gutsy Allison’s father, Cuddy. Ye mind Gutsy.” The pipe-sergeant was searching out new treasures. “Save us, see there.” He pointed to a picture of the ’twenties. “Behold the splendour there, Mr MacNeill.” I looked at a face in the back rank, vaguely familiar, grim and tight-lipped. “He’s filled out since then,” said the pipe-sergeant. “Seventeen stone of him now, if there’s an ounce. That’s our present Regimental Sergeant-Major. Anderson, McColl, Brand, Hutcheson—”

“Hutcheson got the jail,” said Cuddy. “He played the fiddle for his recreation, and went poaching with snares made from violin strings. An awfy man.”

They chattered on, or at least the pipey chattered, and I made polite murmurs, and at last they ran my great-uncle to earth, reclining at the end of a front row and showing his noble profile in the Victorian manner. Showing as much of it, anyway, as was visible through his mountainous beard: he gave the impression of one peering through a quickset hedge.

“Fine, fine whiskers they had,” cried the pipe-sergeant admiringly. “You don’t get that today. Devil the razor there must have been among them, the wee nappy-wallahs of India must have done a poor, poor trade at the shaving, I’m thinking. He’s a fine figure, your respected great-uncle, Mr MacNeill, a fine figure. Ye have the same look, the same keek under the brows, has he not, Cuddy? See there,” and he pointed to the minute portion of my ancestor that showed through the hair, “isn’t that the very spit? Did ye know him, sir?”

“No,” I said. “I didn’t. He died in South Africa, of fever, I think.”

“Tut, tut,” said the pipe-sergeant. “Isn’t that just damnable? No proper medical provisions then, eh, Cuddy?”

I was studying the picture—“Peshawar, 1897”, it was labelled—and thinking how complete a stranger one’s closest relative can be, when a voice at my elbow said formally:

“Good evening, sir,” and I turned to find the impressive figure of the R.S.M. beside me. He nodded in his patriarchal style—even without his bonnet and pace-stick he was still a tremendous presence—and even deigned to examine great-uncle’s likeness.

“If he had lived I would have known him,” he said. “I knew many of the others, during my boy service. You have a glass there, Mr MacNeill? Capital. Your good health.”

The mess was beginning to fill up now, and as we chatted under the pictures one or two others joined us—old Blind Sixty, my company quarter-master, and young Sergeant McGaw, who had been organiser of a Clydeside Communist Party in civilian life. “How’s Joe Stalin these days?” demanded the pipe-sergeant, and McGaw’s sallow face twitched into a grin and he winked at me as he said, “No’ ready tae enrol you, onyway, ye capitalist lackey.”

They gagged with each other, and presently I finished my drink and straightened my sporran and said I should be getting along …

“Have you shown Mr MacNeill his forebear’s other portrait?” demanded the R.S.M., and the pipey, at a loss for once, said he didn’t know there was one. At which the R.S.M. moved majestically over to the other wall, and tapped a fading print with a finger like a banana. “Same date, you see,” he said, “’97. This is the battalion band. Now, then … there, Pipe-Sergeant MacNeill.” And there, sure enough, was the ancestor, with his pipes under his arm, covered in hair and dignity.

The pipe-sergeant squeaked with delight. “Isn’t that the glory! He wass a pipe-sergeant, the pipe-sergeant, like myself! And hasn’t he the presence for it? You can see he is just bursting with the good music! My, Mr MacNeill, what pride for you, to have a great-uncle that wass a pipe-sergeant. You have no music yourself, though? Ach, well. You’ll have a suggestion more of the Antiquary before ye go? Ye will. And yourself, Major? Cuddy? McGaw?”

While they were stoking them up, the R.S.M. drew my attention to the band picture again, to another figure in the ranks behind my great-uncle. It was of a slim, dark young piper with a black moustache but no beard. Then he traced down to the names underneath and stopped at one. “That’s him,” he said. “Just a few months, I would say, before his name went round the world.” And I read, “Piper Findlater, G.”

“Is that the Findlater?” I asked.

“The very same,” said the R.S.M.

I knew the name from childhood, of course, and I suppose there was a time when, as the R.S.M. said, it went round the world. There was the little jingle that went to our regimental march, which the children used to sing at play:

Piper Findlater, Piper Findlater,

Piped “The Cock o’ the North”,

He piped it so loud

That he gathered a crowd

And he won the Victoria Cross.

There are, as Sapper pointed out, “good V.C.s” and ordinary V.C.s—so far as winning the V.C. can ever be called ordinary. Among the “good V.C.s” were people like little Jack Cornwell, who stayed with his gun at Jutland, and Lance-Corporal Michael O’Leary, who took on crowds of Germans singlehanded. But I imagine if it were possible to take a poll of the most famous V.C.s over the past century Piper George Findlater would be challenging for the top spot. I don’t say that because he was from a Highland regiment, but simply because what he did on an Afghan hillside one afternoon caught the public imagination, as it deserved to, more than such things commonly do.

“Well,” I said. “My great-uncle was in distinguished company.”

“Who’s that?” said the pipey, returning with the glasses. “Oh, Findlater, is it? A fair piper, they tell me—quite apart from being heroical, you understand. I mind him fine—not during his service, of course, but in retirement.”

“I kent him weel,” said Old Sixty. “He was a guid piper, for a’ I could tell.”

“A modest man,” said the R.S.M.

“He had a’ the guts he needed, at that,” said McGaw.

“I remember the picture of him, in a book at home,” I said. “You know, at Dargai, when he won the V.C. And then it came out in a series that was given away with a comic-paper.”

“Aye,” said the pipe-sergeant, on a triumphant note, and everyone looked at him. “Everybody kens the story, right enough. But ye don’t ken it all, no indeed, let me tell you. There wass more of importance to Findlater’s winning the cross than just the superfeecial facts. Oh, aye.”

“He’s at it again,” said Old Sixty. “If you were as good at your trade as ye are at bletherin’, ye’d have been King’s Piper lang syne.”

“I’d be most interested to hear any unrelated facts about Piper Findlater, Pipe-sergeant,” said the R.S.M., fixing him with his eye. “I thought I was fully conversant wi’ the story.”

“Oh, yes, yes,” said the pipey. “But there is a matter closely concerned with regimental tradition which I had from Findlater himself, and it’s not generally known. Oh, aye. I could tell ye.” And he wagged his head wisely.

“C’mon then,” said McGaw. “Let’s hear your lies.”

“It’s no lie, let me tell you, you poor ignorant Russian lapdog,” said the pipey. “Just you stick to your balalaikeys, and leave music to them that understands it.” He perched himself on the arm of a chair, glass in hand, and held forth.

“You know how the Ghurkas wass pushed back by the Afghans from the Dargai Heights? And how our regiment wass sent in and came under torrents of fire from the wogs, who were snug as foxes in their positions on the crest? Well, and then the pipers wass out in front—as usual—and Findlater was shot through first one ankle and then through the other, and fell among the rocks in front of the Afghan positions. And he pulled himself up, and crawled to his pipes, and him pourin’ bleed, and got himself up on a rock wi’ the shots pingin’ away round him, and played the regimental march so that the boys took heart and carried the crest.”

“Right enough,” said Old Sixty. “How they didn’t shoot him full of holes, God alone knows. He was only twenty yards from the Afghan sangars, and in full view. But he never minded; he said after that he was wild at the thought of his regiment being stopped by a bunch o’ niggers.”

Sergeant McGaw stirred uncomfortably. “I don’t like that. He shouldn’t have called them niggers.”

“Neither he should, and you’re right for once,” said the pipey. He sipped neatly at his glass. “They wass not niggers; they wass wogs. Any roads, they carried him oot, and Queen Victoria pinned the V.C. on him and said: ’You’re a canny loon, Geordie’, and he said, ‘You’re a canny queen, wifie’, and—”

The R.S.M. snorted. “He did nothing of the sort, Pipesergeant.”

“Well, not in so many words, maybe,” conceded the pipey. “But here’s what none of you knows. The papers wass full of it, how he had played the regimental march under witherin’ fire, and ’Cock o’ the North’ was being sounded up the length and breadth of the land, in music halls, and by brass bands, and by street fiddlers, and everybody. The kids wass singing it. And Findlater, when his legs wass mended, suddenly took thought, and said to his pal, the corporal piper, ‘Ye know, I’m no’ certain, but I doubt it wass the regimental march I played at all. I think it was “Haughs o’ Cromdale”.’

“The corporal piper considered this, and cast his mind back to the battle, and said Findlater was right. It wasnae ’Cock o’ the North’ at all, but he didnae think it was ’Haughs o’ Cromdale’ either; by his recollection it was ‘The Black Bear’.

“They argued awa’, and got naewhere. So they called on the Company Sergeant-Major, who confessed he couldnae tell one from t’ither, but thought it might have been ‘Bonnie Dundee’.

“Finally, it got to the Colonel’s ears, and he wass dismayed. Here wass the fame of Piper Findlater ringin’ through the land, and everyone talking about how he had played ‘Cock o’ the North’ in the face of the enemy, and the man himself wasnae sure what he had played at all. There wass consternation throughout the battalion. ’A fine thing this,’ says the Colonel. ‘If this gets out we’ll be the laughin’-stock o’ the Army. Determine at once what tune he played, and let’s have no more damned nonsense.’

“But they couldn’t do it. Every man who had been within earshot on the Dargai slope, as soon as you asked him, had a different notion of what the tune was, but how could they be sure, with the bullets flying and them grappling with their bayonets against the Khyber knives? You have to have a very appreciative ear for music to pay much heed to it at a time like that. One thing they decided: there was general agreement that whatever he played, it wasn’t ‘Lovat’s Lament’.”

“Lovat’s Lament” is a dirge; played with feeling it can make Handel’s largo sound like the Beatles.

The pipe-sergeant beamed at us. “Well, there it was. No one was certain at all. So the Colonel did the only thing there was to do. He sent for the Regimental Sergeant-Major. ‘Major,’ says he, ‘what did Piper Findlater play on the Dargai Heights?’

“The R.S.M. never blinked. ’“Cock o’ the North”, sir,’ says he. ‘Ye’re sure?’ says the Colonel. ‘Positive,’ says the R.S.M. ‘Thank God for that,’ says the Colonel. And it was only later that it occurred to him that the R.S.M. had not been within half a mile of Findlater during the battle, and couldn’t know at all. But ‘Cock o’ the North’ the R.S.M. had said, and ‘Cock o’ the North’ it has been ever since, and always will be.”

Sergeant McGaw made impatient noises. “What the hell did it matter, anyway? They took the heights, and he won his V.C. It would have been just the same if he had been playin’ ‘Roll out the barrel’.”

The pipe-sergeant swelled up at once. “You know nothing, McGaw. You have neither soul nor experience. Isn’t it important that regimental history should be right, and that people shouldn’t have their confidence disturbed? Suppose it was to transpire at this point that Nelson at Trafalgar had said nothing about England expecting, but had remarked instead that he was about due for leave, and once the battle was over it was him for a crafty forty-eight-hour pass?”

“Not the same thing at a’,” said McGaw.

“You’re descending to the trivial,” said the R.S.M.

“The country would degenerate at once!” cried the pipe-sergeant, and at this point I finally made my excuses, thanked them for their hospitality, and left them in the throes of philosophic debate.

Back in our own mess, I mentioned to the Colonel that I had been entertained by the sergeants, and had heard of the Findlater controversy. He smiled and said:

“Oh, yes, that one. It comes up now and then, not so often now, because of course the survivors are thinning out.” He sighed. “He was a great old fellow, you know, Findlater. I used to see him going about. Indeed, touching on the pipe-sergeant’s story, I even asked him once what he did play at Dargai.”

“What did he say?”

“Wasn’t quite sure. Of course, he was an old man then. He had an idea it might have been ‘The Barren Rocks of Aden’. Or possibly ’The 79th’s Farewell to Gibraltar’. I had my own theory at one time, I forget why, that it must have been ‘The Burning Sands of Egypt’.”

I digested this. “So it’s never been settled, then?”

“Settled? Of course it has. He played ‘Cock o’ the North’. Everyone knows that.”

“Yes, sir, but how do they know?”

The Colonel looked at me as at a rather dim-witted child. “The R.S.M. said so.”

“Of course,” I said. “Foolish of me. I was forgetting.”

Guard at the Castle

It is one of the little ironies of Army life that mounting guard is usually more of an ordeal than actually standing guard. And frequently the amount of anguish involved in mounting is in inverse proportion to the importance of the object to be guarded. For example, as a young soldier I have been turned out in the middle of the night in jungle country, unwashed, half-dressed, with a bully-beef sandwich in one hand and a rifle in the other, to provide an impromptu bodyguard for the great Slim himself; this was accomplished at ten seconds’ notice, without ceremonial. On the other hand, I have spent hours perfecting my brass and blanco to stand sentry on a bank in Rangoon which had no roof, no windows, and had been gutted by the Japanese anyway.