Полная версия

RISINGTIDEFALLINGSTAR

One autumn morning, after a terrific storm that had swept over the Cape and depressed my spirit with its violence, I woke at dawn to find the sea in front of Pat’s house filled with cormorants, hundreds of them. Driven off the breakwater, they’d gathered in a dense raft, avian refugees in an abstract arrangement, each sharp upturned yellow bill, white throat and sinuous neck creating a repeated rhythm, a crazy cormorant expressionism. A scattering of sea crows, marks on the water.

Some perched on the rotting remains of the old wharf, its stanchions reduced, storm by storm, to forty-five-degree angles sticking up out of the water. I watched as the birds rose and fell as one with the swelling waves. Later, I saw them further out. They’d found a source of food, and as the sun glinted on their bobbing bodies they were overflown by herring gulls, a flickering grey layer to their inky black shapes. It was a frenzied, silent scene, watched only by me.

Most mornings, I walk down the beach to meet Dennis and his dog, Dory. Dennis is handsome and everyone loves him. He’s sturdy, with salt-and-pepper hair and a trim beard; he reminds me of Melville. When we get off the whalewatch boat it takes us three times as long to get home, because he stops so often to talk to friends and acquaintances in town. Dennis was once a teacher; he did his national service in the coastguard, but has loved birds ever since he was a boy growing up in Pennsylvania. He came to Provincetown by chance, and stayed. Everyone’s a washashore here, like the soil itself, brought as ballast to these unstable sands; even the turf came from Ireland, to be laid as lawns for the gracious gardens of the East End.

That morning, as Dennis and I walked towards each other, I saw a bird crouched on the rocky groyne in between us. It had tucked its head into its wings; I presumed it was preening, or sleeping. But as we drew near, Dennis took up his binoculars. Something was wrong. He gestured at me with open hands and then at the cormorant, which slipped off the rocks and into the water.

The bird’s bill was lashed to its back by fishing line, and it was tugging pathetically at the monofilament. We followed as it swam parallel to shore. It wanted to return to the land, confused by what had happened to it, as if it might peck off its trusses. But each time we approached, it went back to the water. Dennis was not optimistic. ‘It’ll just keep swimming out – or it’ll dive,’ he said.

I waded into the sea. Dennis ran further up the beach, staying close to the bulkheads to keep his profile low. I tried to splash the cormorant ashore. It worked: the bird made for the beach and Dennis dashed towards it, unafraid of its flapping bulk.

Suddenly there it was, in our hands. A startling sapphire circle around a green cabouchon eye; a fractured sharpness, staring back unblinking. Up close, every feature took on the definition that Pat had drawn: the yellow-tipped bill and its hooked tip, the matt black wings. Primeval enough from afar, this near the bird looked even more like an archaeopteryx on the beach; evolution in our fingers.

Any bird exists apart from us: unmammalian, and therefore uncanny. Yet I could imagine myself a cormorant mate, entranced by this handsome fellow, building a nest on the rocks, proudly holding our bills in the air in celebration of our cormorantness. We took the bird to the deck of a beach house under construction, where a workman produced a knife. Swiftly, Dennis cut the line and pulled the hook from the cormorant’s mouth. Blood trickled out, bright and fresh against the black feathers. Dennis was promptly pecked on the thumb for his trouble, drawing his own blood in turn. I unwound the bird’s bound wings. In a second it was free, half running, half flying back to the water for its lunch.

After a day of louring greyness, when the town seems bowed down by the low pressure – ‘Everyone I meet says they have to go home and sleep,’ says Pat – I retreat to my studio in the timber house. Its double gables rise over the beach like some Nordic chapel or a barn raised by settlers, held up by a pair of cinderblock chimneys. I sleep in its eaves, in an attic like a chandler’s loft or a ship’s prow. At night I climb up to my platform bed via a wooden ladder, ascending to my dreams, descending in the morning, clambering down backwards the way I would at the stern of a boat.

The house is a fragile and sturdy construction, built to withstand three hundred and sixty degrees and three hundred and sixty-five days of weather. In the winter the wind worries at its windows, with their layers of glass and screens, grooves and latches, a complicated, ultimately ineffectual system of defence. No one wins against the wind, not even these wind’s eyes. Running in front of the house is the deck, a wide wooden stage over which Pat lays a path of threadbare yard-sale rugs to stop its splinters from entering her bare feet. They lend the boards a tattered luxury, like some trampled boudoir. Stirred by the wind and rain, they take on a life of their own, rucking like a ploughed field out of which ever-larger splinters sprout as spiky seedlings.

The whole house is still partly tree. The knots in its walls have fallen out over the years, leaving spy-holes and escape routes for whatever creeps and scratches about inside. There are so many compartments, cupboards, stairs and crawl spaces – so many spaces within spaces – that there could be colonies of creatures living under its eaves. Even as I write this, I discover a narrow staircase which I had never seen before in all the years I’ve been staying here, hidden in a cupboard and leading to the top floor like some secret escape route. And when I open the built-in linen closet on the first floor, a cat hisses at me, leaps up a shaft and disappears into an interior where, for all I know, an entire community of feral felines might reside. I sleep with bare boards next to my head, stamped with the timber merchant’s marks,

MILL 50 MILL 50 MILL

W.C.

L.B. ®

UTIL 3/4 W.R. CEDAR

and occasionally silverfish run up and down the western red cedar, their filigree antennae feeling their way like tiny lobsters, while mice scratch in the eaves. I feel the weather and the sea through the wooden walls and the way the day arrives and the night leaves, and there’s sand instead of biscuit crumbs in my sheets. Sometimes the whole house becomes a woodwind instrument played by a demented child. Doors rattle, urgent spirits seeking admission. Timbers creak as a ship caught in ice; articulated chimney cowls squeak like weather vanes turning in the wind. The house reverberates as though remembering how it was built, an echo chamber resonant with everything happening outside and everything that ever happened within. It may be inanimate, but it makes me more alive, this big beach hut. How could anyone not feel that way, knowing that out there is the sea, and all land is lost to the horizon?

The front hits us, head on. The waves, which yesterday lapped the footings of the house, turn over themselves in their remorseless assault on the bulkhead that acts as a buffer between the house and the sea. Town regulations, designed to allow the shifting sand its sway, mean that even the most luxurious decks and dining rooms are temporary arrangements. Pat’s house, now in its sixth decade, was built to be part of rather than apart from the water; in stormy spring tides the sea actually runs right underneath it, disdaining its foundations. By the end of the century all those exclusive properties and ramshackle shacks alike will yield to the waves. ‘The truth is,’ the philosopher Henry David Thoreau wrote on one of his visits to the Cape, ‘their houses are floating ones, and their home is on the ocean.’

Directly in front of the house is a raft tethered by a chain to the sea bed. It’s another stage, a four-foot-square island of performance. In the winter seals lounge on it, their doggy heads and flappy feet held in the air to keep warm. Summer visitors think the raft is built for human swimmers; they soon realise that it’s covered in deposits from its other tenants, the eider ducks that take up winter leases, and for whom it is a safe perch even when it rocks wildly in high seas.

Pat and I watch a duck and drake circling the float as if sizing it up. The male makes the first move, followed by his partner. They stake out their separate corners, like a couple seeking their own space. Another male appears with his mate; she is allowed on board, he is rebuffed by the first male. It’s a stand-off. There follows a ritual puffing up of chests and fluttering of wings, like a contest on the dance floor. The inevitable compromise is reached, and the newcomers are admitted. Soon, in the niceties of eider choreography, a third couple arrive and the same rite is observed. All their gestures and cooing, which seem quaint to our anthropomorphic eyes – as if they were saying to each newcomer, ‘No room, no room’ – are in fact grim and determined expressions of potential violence and struggle for precedence.

Eiders are another of this shore’s animal spirits. They preside, like the cormorants and the seals, imbued with their own inscrutability. The raft is their portal: I imagine them diving off it and coming up in a willow-pattern world to reassume their imperial presence, shrugging their lordly wings as they do so. They may be the largest of the ducks, but they’re also the fastest bird in level flight, able to fly at seventy miles an hour against fierce nor’easterlies. They are endlessly interesting to me, seen from my deck or through my binoculars. Their heads slope down to wedge-shaped bills, redolent of Roman noses or a grey seal’s snout. Their black eye patches and pistachio-green napes look like exotic make-up, although Gavin Maxwell thought that they wore the full-dress uniform of a Ruritanian admiral. Their table manners are hardly refined: they use their gizzards, lined with stones, to grind and crush the mussels and crabs which they swallow whole. Birds as machines.

They too have suffered. In Britain they were used for target practice during the Second World War; thousands of them, lying in rafts on the sea, were blasted away. On the Cape that winter I find many eider carcases strewn across the sand, ripped open and spatchcocked, as if the violent cold were too much even for them, despite their downy insulation. One victim’s eyes have long since puckered into blindness, but its nape is still tight, like the back of a rabbit’s neck, more fur than plumage. Eiders are still harvested for their air-filled feathers to make quilts and coats, ‘robbing the nests and breasts of birds to prepare this shelter with a shelter’, as Thoreau wrote. They tolerate our appropriation; they have no choice. But while we may have our uses for them, their features speak of something unknowable.

Perhaps it is those eyes. Yes, it’s those eyes. It always is. They take in the whole of the world, even as they ignore it.

Held out into the Atlantic, Cape Cod is a tensed bow, curled up and back on itself, a sandy curlicue which looks far too fragile to withstand what the ocean has to throw at it. Battered by successive storms, its tip has been shaped and reshaped for centuries. It is only halfway here, and not really there at all. It is porous. The sea seeps into it.

This is where America runs out. Sometimes, if the light is right, as it is this morning, the land across the bay fizzles into a mirage, a Fata Morgana stretching distant beaches into seeming cliffs, floating dreamily on the horizon. The further away you are, the less real everything else becomes. This place takes little account of what happens on the mainland; or rather, puts it all into perspective. It is a seismograph in the American ocean, sensing the rest of the world. Not for nothing did Marconi send out his radio signals from this shore; he also believed that in turn his transmitters might pick up the cries of sailors long since drowned in the Atlantic.

The inner bay arches around from the lower Cape, losing people as it goes. From empty-looking lanes where signs politely protest THICKLY SETTLED, as if there might be as many inhabitants as trees, you pass through Wellfleet’s woods and second homes to North Truro’s desultory holiday cottages on the open highway, as lonely as Edward Hopper’s paintings, and on to Provincetown, where the land widens briefly before dwindling to Long Point, a spit of sand as slender and elegant as the tail on the tiny green spelter monkey that sits above Pat’s woodstove. Long Point Light stands on the tip, a square stubby tower topped with a black crown lantern – it might welcome or warn off visitors, it doesn’t really matter which. Once you’re here, you never leave. This is the end and beginning of things.

I first came to Provincetown in the summer of 2001. Invited here by John Waters, I was in town for just five days; I had no idea then what they would mean to me now. Like some perverse mentor, John initiated me into the secrets of the place. We drank at the A-House, where grown men groomed one another’s bodies like animals eating each other’s fleas; and we drank at the Old Colony, a wooden cave that lurched as if it was drunken itself; and we drank at the Vets bar, where the straight men of the town took their last stand in the dingy light. On hot afternoons we hitched to Longnook, using a battered cardboard sign with our destination scrawled on it with a Sharpie, waiting on Route 6 for a ride. Once a police car stopped for us. We sat on the caged back seat like criminals and when we arrived, John said, ‘We’ve been paroled to the beach.’ He looked out over the ocean and declared it to be so beautiful that it was a joke. When he rode down Commercial Street on his bike with its wicker basket like the Wicked Witch of the West, I heard someone call ‘Your Majesty’ as we passed.

It was only at the end of my stay, about to take the ferry back to Boston, that I decided to go on a whalewatch. I stepped off the land and onto the boat. Forty minutes later, out on Stellwagen Bank, a humpback breached in front of me. It still hangs there.

It is not easy to get here. It never was. For most of its human history, Provincetown was accessible only by boat, or by a narrow strip of sand that connected it to the rest of the peninsula. And even when you did arrive, it was difficult to know what was here and what was there; what was land and what was sea. Maps from the eighteen-thirties show a place marooned by water, its margins partly inundated. There was no road till the twentieth century; the railway once raced visitors to Provincetown, but that was abandoned long ago, as were the steamers that brought trippers from New York. Nowadays ferries run only from May to October, and the little plane can be grounded by lightning striking the airstrip or fog shrouding the Cape. Provincetown is where Route 6 starts, running coast to coast for three and a half thousand miles all the way to Long Beach, California. But it was renumbered in 1964, and now North America’s longest highway seems to peter out in the sand, as if it had given up before it began. It is a long, long drive here from Boston, and the road becomes progressively narrower the further you go, curling back on itself till the sea presses in from all sides, leaving little space for tarmac, houses, or people. No one arrives here accidentally, unless they do. It is not on the way to anywhere else, except to the sea.

The lost people who find their way here discover the comfort of the tides, anchoring endless days which would spin out of control, faced with the wilderness all around. My time is defined by the sea, just as it is at home. But instead of having to cycle to it, I only have to roll off my bed, and stumble down the wooden steps. I sniff the air like a dog, and lower myself off the bulkhead. The eiders coo like camp comedians. The water is the water. I turn on my back, face up to the sky, the monument high on the hill behind me marking the arrival of the Pilgrims who set sail from Southampton for this shore three centuries ago. I swing my body towards it like a compass needle. It’s as though I’d swum all the way here. I count my strokes. The cold soon forces me out. I climb back upstairs to boil water for tea, holding my hands over the glowing electric element to restore the circulation enough to let me write.

On my desk sit the objects that spend my absence stashed away under the eaves like Christmas decorations. A swirly green glass whale I bought from the general store. A nineteen-twenties edition of Moby-Dick, a faded coloured plate stuck on its cover. A slat of driftwood found on the beach, with layers of green and white paint peeling away in waves. A tide table pinned to the wall, although I don’t really need it. My body is tuned to the ebb and flow; I hear it subconsciously in my sleep, and feel it wherever I am in town. Everyone else feels it too, even if they think they don’t. It stirs me from my bed and summons me to the sea, whatever the time of day or night.

I’ve spent many summers here; winters, too. I’ve seen it out of season, when the people fall away with the leaves to reveal its bones: the shingled houses and white lanes lined with crushed clam shells as if they led out of or under the sea. Squeezed on all sides by the sea, houses here are built efficiently, like ships; in a place like this, you don’t waste space or resources. An artist’s studio has drawers built into the risers of the stairs, turning them into one big ascending storage unit. At another cottage, over a glass of gin, I admire a galley kitchen with plates stored on sliding racks. The artist tells me they were designed by the previous owner, Mark Rothko. ‘He made us promise never to change them.’

Provincetown may be a resort to some, but it is at its best at its most austere, when everything is grey and white and hollow, and you can peer over picket fences into other lives; backyards full of buoys or old trucks where a century ago there would have been nets and harpoons. Once this was an industrial site – hunting whales, catching fish. Then it emptied, forgotten by the future which left its people behind, the insular people Melville knew, ‘not acknowledging the common continent of men, but each Isolato living on a separate continent of his own’.

On warm summer nights, Commercial Street, one of only two thoroughfares that thread through the town, is an open, sensual place; in the winter, when the cold comes inside and won’t leave of its own accord for half the year, the rawness returns it to a dark lane, winding nowhere. In 1943, when the town was further shadowed by the threat of air raids and German landings – as if its held-outness was a kind of sacrifice to the war going on across the ocean – the young Norman Mailer walked down the blacked-out street and back into the eighteenth century, or at least what he felt was ‘a close intimation of what it might have been like to live in New England then’. It’s difficult to imagine an inhabited place so empty. Even during the day in the twenty-first century, a chill sea mist can envelop its springtime streets – all the seasons are delayed here – filling the glowing white lanes with ghosts. There are spirits throughout this creaking old town. You see their shadows on stairs, shapes out of the corner of your eye. In the winter, they walk down the street. They’re there in the summer too; they just look like everybody else.

The sea accelerates and stalls time. This town has altered in many ways, even in the fifteen years I have been coming back to it, for all that it stays the same. I’m never quite sure when I return that I will be accepted by its people, its weather, its animals, or that anyone will remember me, and am always surprised when they do. I’m always arriving and always leaving; as my friend Mary across the street says, the moment you arrive anywhere is the start of your departure. Life here is measured by the waiting for spring, the longing of the fall, the waiting for summer, the longing of winter; everything is restless, like the sea. Sometimes it seems so perfect that I wonder if it even exists, if it isn’t all a vision which rises through the plane’s windscreen as I arrive and disappears off the ferry’s stern as I leave; and sometimes I wonder why I come here at all, when the wind whines and voices bicker, when cabin fever takes over and doors blow back in your face.

This is not a kind place. It leaves its inhabitants biopsied, like the scars in skin too long exposed to the sun. Lungs collapse with too much cold air. Like their forebears, they suffer for presuming to live on this frontier. It is a continual challenge to body and mind. A place of dark and light, day and night, storms and tides and stars; a place where you have to feel alive, because it so clearly shows you the alternative.

Pat’s house is so much of a boat that it might have been floated across from Long Point, as houses were in the nineteenth century, or been trawled out of the bay, like the whaling captains’ mansions down in New Bedford, ‘brave houses and flowery gardens, that came from the Atlantic, Pacific, and Indian Oceans, harpooned and dragged up hither from the bottom of the sea’. Inside her studio, Pat’s state-of-the-art kayak is slung from the rafters alongside an older, wooden model, both hanging there like stuffed crocodiles in a cabinet of curiosities. A large plastic sheet is stretched between them to catch the rainwater that drips from the roof. With typical ingenuity, Pat has rigged up an intricate series of lines and pulleys, along with a plastic tube draining the swelling whale belly of the sheeting like a catheter into a hanging bucket which, when full – as it is from last night’s storm – can be lowered to be emptied, just as Pat’s kayaks can be lowered, ready for the days when she would paddle out to the Point and beyond, not really caring about coming back.

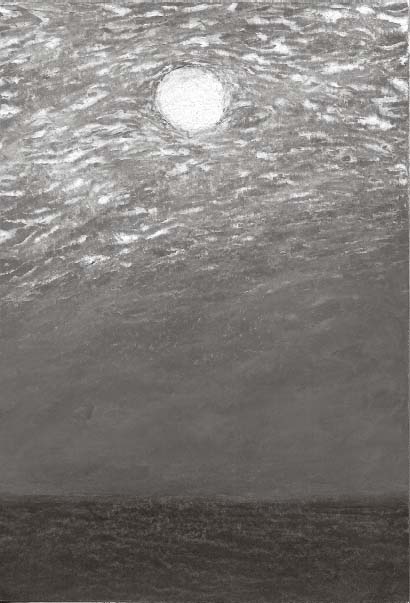

The rigging turns her studio into an inside-out yacht. It is a kinetic work of art in itself. Lightbulbs dangle from electric cords like the lures of angler fish, but there are no bright lights inside because all the light is outside. Doors slide to reveal store cupboards capable of stacking huge canvases like theatre scenery. The whole house is slotted together, a serious plaything, a place to work and be and think and drift along with the seasons. It is part of her body, an extension of her self. It is entirely practical, fitted out rather than built. On the studio walls hang Pat’s paintings of the view outside: the same scene painted again and again, like the cormorants; the same proportion of sea and sky, the same dimensions divided between air and water, in mist and fog and snow and moonlight. They are not so much paintings as meditations. They look through the moment of seeing – the falling fog, the drifting snow, the rising moon. They are the sea reduced to its essence. They are not concepts. Pat’s husband Nanno de Groot told her, ‘Analyse your stupidity.’ ‘I don’t think about anything else when I work,’ Pat tells me. That’s because her work is not like anything else.

She uses no brushes, but applies the paint with a knife; removing, rather than adding, to reveal what was there all along. The paint is flattened, smoothed, pushed in; you can feel the power of her hand and arm and shoulder behind it. But at the same time the colour – the medium between what she sees and what she puts down – rises rhythmically like the waves and clouds it re-presents, grey and green and white and blue. Pat paints the memory of the actuality of the thing – the thing that lies out there. It all comes down to the water. When I admire one painting of a dark sky and a silver sea, she says, ‘I waited half my life to be able to paint that.’

Everything is here; everything disappears. Every window is a frame for her work: windows in her dining room, the windows she looks through from her bed, the windows in her bathroom, the windows in her head. They all admit possibilities and impossibilities; work-in-progress. Her mind is laid out here. You can follow the trail of her imagination from her studio and into her house. Half-squeezed tubes of paint lie under Buddhist prayer flags, next to scraps of sun-yellowed paper and rolls of masking tape, tiny palette knives and piles of fading National Geographic magazines. On a work table is a clam shell in which a finch is curled, quietly sleeping, all but breathing, its perfect feathers still blushed pink.