Полная версия

RISINGTIDEFALLINGSTAR

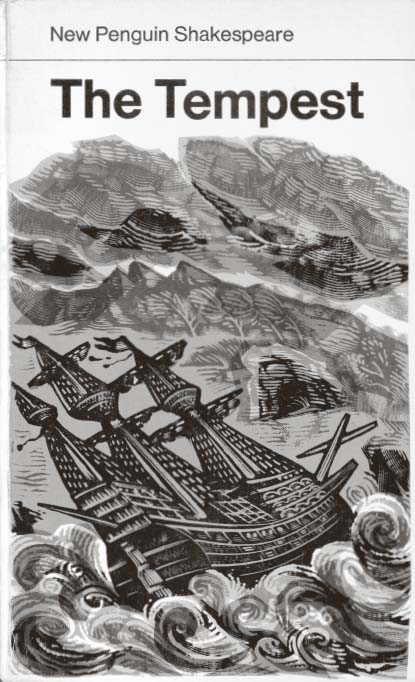

Recently, on a shelf of stranded books being sold to benefit a bird sanctuary overlooking the Solent, I discovered a 1968 Penguin edition of the play. It was an oddly apt place to find it: this silted-up seventeenth-century harbour, overflown by marsh harriers and stalked by godwits and avocets, was the domain of the Earl of Southampton – Harry Southampton, Shakespeare’s Fair Youth and possibly his lover, who lived at nearby Titchfield Abbey, where the playwright’s works were performed.

I paid fifty pence for the book, attracted by its cover, designed by David Gentleman. Splashed with broad swathes of solid colour, the wood engraving, inspired by the work of Thomas Bewick, seemed to span the turbulent year of its nineteen-sixties publication – when protestors lifted up pavement stones, to find the beach below – and the uncertainties of its seventeenth-century contents.

A three-masted ship tilts in a stylised sea, rolling on waves below stormy clouds towards a tree-blown island and a rocky cave, all rendered in sludgy, overlapping shades of subdued blue and green, grey and teal, like the birds and land and sea around the building where I’d bought the book. The design was almost cartoon-like, folkloric, and layered. It caught the dark mystery and music of the words within.

The Tempest is a ceremony, a ritual in itself, publicly performed in a sky-open theatre on the site of the Blackfriars monastery on the Thames, a river into which sacrifices were once thrown to propitiate the gods. It is a pared-back, mysterious work, ‘deliberately enigmatic’, as Anne Righter says in her introduction to the Penguin edition, ‘an extraordinarily secretive work of art’, so emblematic that it might be acted out in mime, without any words at all.

Its origins lay in the fate of Sea Venture, which sank off Bermuda in 1609 while carrying colonists from Plymouth to Jamestown; Harry Southampton himself was an investor in the Virginian settlement. Shakespeare drew on William Strachey’s account of the wreck, a natural history of disaster, with its tales of St Elmo’s fire at the height of the storm – ‘an apparition of a little round light, like a faint Starre, trembling, and streaming along with a sparkling blaze’ – and the eerie calls of petrels coming in to roost, ‘a strange hollow and harsh howling’. Their cries earned Bermuda its reputation as an island of devils, one which Strachey rationally dismissed, although he did acknowledge the presence of other monsters: ‘I forbear to speak what a sort of whales we have seen hard aboard the shore.’

The Tempest is the closest Shakespeare comes to the New World. It is almost an American play, although two centuries later its castaways might have been washed up on another colony: Van Diemen’s Land, on whose remote south-western shores one can still imagine a seventeenth-century shipwreck and its stranded sailors stumbling about on the alien sand. Some saw Caliban and Ariel as symbolic representations of newly-discovered native peoples, whose countries were already being plundered by the West; others have seen a reflection of an island nearer to home: Ireland, a troublesome place filled with its own wild people, and regarded as a plantation to be conquered. But equally, Prospero’s isle might be utopia, a nowhere place over which his magic rises as a mist veiling time and space – just as a century earlier, Columbus, researching his expedition, had written notes and marginalia about strange people cast up on the shores of the Azores and the west of Ireland: ‘We have seen many notable things and especially in Galway, in Ireland, a man and a woman with miraculous form, pushed along by the storm on two logs.’

Shakespeare, nearing the end of his life, appeared to have recreated himself in the omniscient magician; others have seen Prospero as a reflection of Elizabeth I’s astrologer, John Dee, who communed with angels using a golden disc, and peered into his black obsidian mirror – stolen from the New World – in order to see the future and the past. The whole play seems to be happening before it was written. It is fraught in the original sense of the word, as a ship filled with freight, as well as with meaning. Shakespeare was familiar with the ocean: he refers to it more than two hundred times in his works, and some critics believe that he was once a sailor. Certainly he knew its meaning, and set The Tempest on a ‘never-surfeited sea’, a transformative place. After the storm, Ariel tells Ferdinand that his father, the king, lies ‘full fathom five’; he has been made immortal by the water, becoming a baroque jewel in the process:

Of his bones are coral made;

Those are pearls that were his eyes;

Nothing of him that doth fade,

But doth suffer a sea-change

Into something rich and strange.

For the artists and poets who came after, The Tempest lingered in its magical power and deceptive simplicity. Samuel Taylor Coleridge thought that Prospero’s art ‘could not only call up the spirits of the deep, but the characters as they were and are and will be’, and that Ariel was ‘neither born of heaven, nor of earth; but, as it were, between both’. For Percy Shelley, who would be nicknamed Ariel, the play evoked ‘The murmuring of summer seas’ and his own in-between state. And for John Keats, in whose volumes of Shakespeare’s works the play was the most heavily scored, it became a pattern for his imaginative life, like a map to be followed. Indeed, he sailed down Southampton Water with The Tempest in his pocket.

In April 1817, Keats, then a medical student in London, took the coach to Southampton in search of distraction. He had loved the sea ever since he’d read of ‘sea-shouldering whales’ in Spenser’s The Faerie Queene – ‘What an image that is!’; his poetry habit had made him ‘a Leviathan … all in a Tremble’, and in a letter to his friend Leigh Hunt, he evoked ‘a Whale’s back in the Sea of Prose’. But as he walked along the port’s medieval walls and looked down the grey waterway, the young poet did not see what Horace Walpole had seen a generation before, ‘the Southampton sea, deep blue, glistening with vessels’, nor even any of the dolphins which sometimes swam up it. Instead he found muddy shores laid bare at low tide; the sea had run out. ‘The Southampton water when I saw it just now was no better than a low water Water which did no more than answer my expectations,’ he told his brothers, ‘– it will have mended its Manners by 3.’ Keats’s nerves were raw, so he took out his Shakespeare and quoted from The Tempest for solace: ‘There’s my comfort.’ That afternoon he left on the rising tide, sailing to the Isle of Wight where, troubled by the island’s strange noises and unable to sleep, he began his long poem, Endymion, filled with moonbeams and snorting whales and leaping dolphins and the tale of Glaucus, the fisherman-turned-god with fins for limbs, whom Endymion frees from Circe the witch.

Keats’s contemporary J.M.W.Turner was also stirred by the restless sea. His imagination stained southern skies: he sketched this shore and painted storms off the Isle of Wight, and when he claimed to have had himself lashed to a ship’s mast in a blizzard so that he could create a great swirling vortex of waves and cloud – as if he were seeing into the future – he gave the vessel’s name as Ariel. And in this stormy story, Shakespeare and Turner would in turn influence another writer. Herman Melville’s eyes had been damaged by scarlet fever in his childhood and rendered as ‘tender as young sparrows’; he was thirty years old, with a career at sea behind him, when he read Shakespeare, discovering a large-print edition of the playwright’s works in 1849. As he began to write about his great white whale – his head full of Turner’s spumey paintings he’d seen in London that year – Melville read The Tempest and drew a box around Prospero’s ‘quiet words’, the magician’s wry response to his daughter’s naïve exclamation on seeing the aliens:

Miranda. O! wonder!

How many goodly creatures are there here!

How beauteous mankind is! Oh brave new world,

That has such people in’t!

Prospero. ’Tis new to thee

Melville, himself the scion of a colony, saw the prophecy in Shakespeare’s drama and in Turner’s art: both helped him create the strange, ominous world of Moby-Dick. In it, Captain Ahab is a monomaniacal Prospero, and as the opening of The Tempest is lit by St Elmo’s fire, so the same eerie light garlands his ship, the Pequod, in a ghostly glow; animals acquire symbolic meaning – whales and birds accompany the narrative as familiars, swimming and flying alongside the story – and the sea rises up as if with a mind of its own, as it does in Turner’s paintings. Meanwhile mortal men pursue their deadly trade: a restive crew sails into the unknown – among them a tattooed cannibal, Queequeg, a kind of Caliban – and Ahab blasphemously baptises his harpooneers in the name of the devil. Nor would the American’s fascination with Shakespeare’s play end there. At the end of his own last work, Billy Budd, Melville imagines the hanged body of his Handsome Sailor consigned to the deep, entangled in oozy weeds; it is an echo of Jonah’s fate in a biblical sea – ‘where the eddying depths sucked him ten thousand fathoms down, and the weeds were wrapped about his head’ – but also of Alonso in The Tempest, who, believing his son to be drowned, wishes he too was ‘mudded in that oozy bed’.

Constantly recreated, constantly re-enacted, The Tempest lived on beyond its creator, passed on from hand to hand. It became a secret cipher, a futuristic shipping forecast, an extended magical spell. It conjured a queer sea out of its strange beasts and its masquerades, and stood against time and tide even as it rose with them in a storm stirred up by a dramatist whose own identity still seems fluid and uncertain.

As a new century loomed, the play gained momentum, gathering clouds rather than diminishing with distance and time. A few years after Melville left Billy Budd on his desk unpublished, another former sailor, Joseph Conrad, drew on The Tempest for his Heart of Darkness, with Kurtz as a terrible Prospero. Two decades later, Eliot embedded fragments of the play in The Waste Land, as if Shakespeare had foreseen the undone. Eliot’s work was rivered with the brown god of the Thames and the ship-wrecked, sea-monstered coast of New England he’d sailed as a boy; and as his Madame Sosotris lays out the Tarot card of the drowned Phoenician Sailor – ‘Those are pearls that were his eyes’ – she warns ‘Fear death by water.’ Meanwhile, the bones of another sailor, ‘a fortnight dead’, are picked clean by the creatures of the sea, the slimy things the Ancient Mariner saw down there.

Haunted and haunting, The Tempest accompanied the twentieth century as a parallel rite; few other works of art have been so replicated, remodelled, and re-presented. W.H. Auden reimagined its characters’ fates in his verse drama The Sea and the Mirror; Aldous Huxley drew on it ironically for his brave new world; and the science-fiction film Forbidden Planet turned Ariel into Robbie the robot for an era fearful of its own aliens. And at the end of the darkened nineteen-seventies – as a British satellite named Prospero spun into outer space, following its fellow transmitter, Ariel, launched a decade earlier – Derek Jarman, living in a London warehouse on the Thames and fascinated by John Dee, filmed his alchemical version as ‘a chronology of three hundred and fifty years of the play’s existence’, with Prospero played by the future author of Whale Nation, a sibilant blind actor nicknamed Orlando as Caliban, an androgynous man-boy as Ariel, and Elisabeth Welch singing ‘Stormy Weather’ surrounded by dancing sailors. In this lineage of otherness, filled with hermaphrodites and shape-shifters, it does not seem a coincidence that the director wanted Ariel’s songs to be sung by the starman who obsessed me, and who presided over my blue notebook.

The word ‘tempest’ itself derives from the Latin tempus, for time. Everything is new and old on Prospero’s island. Like the sea itself. Always changing, always the same.

Out of the blackness obscure noises drift from the docks, booming over the water. The red lights of the power-station chimney blink like an industrial lighthouse, summoning and warning. You can be what you want to be in the dark. For me, it used to be nightclubs under London streets. Now it’s another nocturnal performance.

An hour before dawn, before the light starts to stain the summer sky violet, I ride back to the beach. Foxes sidle out of the woods and rabbits flash their white scuts at the approach of my bike light. High in the trees over the shore, a pair of tawny owls converse in screeches. Crows hang in the branches, all angular tails and beaks, as if they’d been born out of the boles. All these creatures own this place in the interregnum of the dark; they should not be anywhere else. No one could have told you when you were young what would happen. They didn’t dare. It’s enough to realise that what we have lost is still ahead of us. I see things that are not there.

One magical moment; I feel like a penitent. The sea is so still it seems like a sin to break its surface. But I do. Swimming at night, with diminished sense of sight, only makes the act all the more sensual. You feel the water around you; you lose yourself in its sway. Fish bite me, leaving loving grazes.

I turn on my back, watching the stars fall.

I first saw it slumped on the weedy slipway one afternoon. A deer, sprawled at the high water mark. It looked perfect, lying there, thrown up by the tide, staring glassy-eyed to the sky. Had it died trying to swim across from the forest? Or had it slipped and fallen, cloven hoofs clattering on the concrete with panic in its eyes? Perhaps it had been shot, although there was no wound in its russet pelt.

The next day someone had hauled out this sea-deer, this antlered seal, and impaled it on the spikes of the metal railings. It hung there by its neck, dangling as a warning, the way farmers nail dead owls, wings outstretched, to barn doors. I wanted to relieve it of this indignity, to take it down from its cross, but I hadn’t the strength.

So I waited to see what happened next.

The following day it reappeared on the shore, as if it had climbed down overnight. It was accompanied by a carrion crow, tentatively but intimately pecking away at the flesh, performing the last rites. I wished the bird well, and a good breakfast.

I’d forgotten about the carcase when, a week later, I came across its remains in the surf. By now the body had been reduced to a single strand of vertebrae, picked clean by crabs and gulls. It was down to its essential scaffolding, its skeletal beauty twisted like the ghost of a horned sea serpent lolling in the water. The stubby antlers sprouted from the bulbous, rough-edged rings on the forehead; caught between them was a scrap of fetlock-like fur. Skeins of grey flesh still hung about the skull, scrappily attached to the thin white bone. I had to have it, this grotesque piece of flotsam, something to add to the pile back home, the fragments of blue-and-white china, the clay pipes with the bloom still on them, the shards of misty sea-glass, the chunks of green-glazed medieval pots, the stones pierced with holes.

Using a bit of driftwood to hold down the spine, I pulled at the antlers, twisting and wrestling with them as with a bull. It occurred to me, as I did so, how easy it might be to detach a human head. With a stagger, I succeeded in wrenching off my trophy, my prize for having watched so patiently. I had to gouge out a gelatinous eye before stuffing the skull into a plastic bag and tying it to the back of my bike.

I rode away from the beach, passing walkers who wouldn’t guess at my cargo. Back home I opened a hole in the warm brown earth and buried the head up to its antlers. They stood proud of the soil like a pruned rose bush. I piled rocks on top to guard against predators and went back indoors to wait till the antlers sprouted and grew like branches, and as below the surface the skull grew roots which became bones, its lost vertebrae, femurs and ribs all restored, ready to rear up out of the earth, a resurrected, a newly-grown deer of my own.

HEGAZESTOTHESHORE

The runway is spattered with coloured lights, a constellation fallen from the sky. I’m led out into the sharp night air, and take my place beside the pilot. He tells me to slide my seat forward and strap myself in. The dual controls move over my lap, operated by a ghostly co-pilot; incomprehensible dials and LED displays tick and flicker on the console. The plexiglass windows shake with the propellers as we taxi onto the airstrip. We stand ready for takeoff, behind a huge airliner, the kind in which I’ve just spent six hours getting here. But these last few miles seem the most difficult.

The little plane follows the behemoth, drawing courage from its slipstream. The pilot mutters into his microphone, the runway clears and the wings wobble. Suddenly we are rising over the dark city, made darker by the sea at its edge.

I have to catch hold of my breath, like a child on Christmas morning. I want to turn to the pilot and say, Isn’t this amazing? But he just stares ahead, wearing his white pressed shirt, quietly suppressing his ecstasy. Everything falls away, all the houses and streets and offices and institutions, leaving only the black water.

The airstrip lights vanish, replaced by winter stars. Orion lurches over the horizon, lazily rising into position, echoing Cape Cod’s fragile shape in his starry frame. The night is so clear, made clearer by the cold, that I can see through the Hunter’s spaces to the stars he has swallowed, the stars that are being born. We’re astronauts for twenty minutes, inside the sky, flying into another system. I look up and down: there’s no difference above or below. The sea is full of stars; the stars are full of the sea.

Out of the blackness ahead a line of red lights appears, trembling, beckoning us down. It is a tentative landfall: the only thing below us is sand. We return to earth with a bump. For all I know we might have arrived on another planet. Then the pilot turns round in his seat and says, ‘Welcome to Provincetown.’

These past few days the bay has been filled with mergansers. They’re saw-beaked, punk-crested birds, forever roving over the sea in their search for food or sex. Just offshore, three males arch their necks in lusty splendour, fighting over a female. Pat says black-backed gulls sometimes take them. Pat is my landlady, although sealady might be a better term. She’s lived here for seventy years. She knows this place as well as her own body. It is through her eyes that I see it.

Close up, red-breasted mergansers are even more extreme: big, pugilistic, as though they’re cruising for a fight. I see the detached head of one rolling in the tideline. I pick it up, running my index finger along its velociraptor teeth. This winter beach is no place of innocence and play, but a site of carnage and slaughter.

From my deck I hear the forlorn calls of loons drifting across the bay. In the mid-distance is the rocky, guano-spotted breakwater. It was built to protect the harbour, but it was soon colonised by cormorants. They’re despised for their droppings that dribble like fishy porridge, and for their supposed depletion of the fishermen’s catch; so greedy that they dislocate their jaws to swallow fishes whole. Only Pat sees them for what they are: sentinel creatures she has drawn over and over again, kayaking out to the breakwater and tethering to a lobster buoy, Zeiss binoculars in one hand and a black marker pen in the other.

Pat – who resembles a bird herself, with her shock of silver hair, intense brown eyes and high cheekbones – channels these charismatic spirits. Haughty of our disdain, they pose in portrait after portrait, a cormorant lineage, each profile worthy of a Hapsburg prince. Clamped to the rocks by their claws, heads bent to preen or raised to the sky, they hold out their wings – to cool their bodies as much as to dry their feathers – casting shadows of themselves. Some saw the crucifix in the shape they threw, a symbol of sacrifice; others discerned something darker.

In the opening pages of Jane Eyre, published in 1847, Charlotte Brontë’s young heroine takes Thomas Bewick’s A History of British Birds from a library shelf on a winter’s afternoon, and hiding in a curtained window seat, loses herself in descriptions of ‘the haunts of sea-fowl’ in the Northern Ocean, surrounded by ‘a sea of billow and spray’ and the ‘marine phantoms’ of wrecked ships.

Bewick’s engravings of ‘naked, melancholy isles’ echo Jane’s abandonment as an orphan, ‘an uncongenial alien’. Later, when she meets Mr Rochester, she shows him three strange watercolours she has painted. One portrays a woman’s body from the waist up, seen through a vapour as the incarnation of the Evening Star; another depicts an iceberg under a muster of the northern lights, overloomed by a veiled and hollow-eyed head. In the third allegory, a cormorant perches on the half-submerged mast of a sinking ship. The bird is ‘large and dark, with wings flecked with foam; its beak held a gold bracelet set with gems, that I had touched with as brilliant tints as my palette could yield, and as glittering distinctness as my pencil could impart’. Below it, ‘a drowned corpse glanced through the green water; a fair arm was the only limb clearly visible, whence the bracelet had been washed or torn’.

The double-crested cormorant’s binomial, for all its Linnaean rigour, is resonant of such gothic airs. Phalacrocorax auritus conflates the Greek for bald, phalakros, and korax, for crow or raven, with auritus, the Latin for eared, a reference to the bird’s breeding crests. Its common name also reflects the same allusion, if not confusion, as a contraction of corvus marinus, sea raven – until the sixteenth century it was believed that the two species were related. Indeed, like ravens, cormorants have a noble antecedence: James I kept a cormorantry on the Thames, overseen by the Keeper of the Royal Cormorants who hooded his charges and tied their necks to stop them swallowing their prey. Bewick called them corvorants and thought their tribe ‘possessed of energies not of an ordinary kind; they are of a stern sullen character, with a remarkably penetrating eye and a vigorous body, and their whole deportment carries along with it the appearance of the wary circumspect plunderer, the unrelenting tyrant’; he noted that Milton’s Satan perches as a cormorant in Paradise, a banished black angel on the Tree of Life.

The cormorant, whose darkness is implicit in its ability to dive one hundred and fifty feet into the sea, predates any tyrannical monarch; its pterosaur pose evokes the reptilian past of all avians. But to some modern eyes, the cormorant is all too common: a scavenger, a sea crow, or, in the careless calling of the American deep South, the nigger goose. According to Mark Cocker, British anglers call it ‘black death’, and demand its execution. But all name-calling reflects only on ourselves: we name to know and own, not necessarily to comprehend. We don’t even have the right words for ourselves.

Like other animals, cormorants have been forced to share the human stain. Far from eating ‘our’ fish, the prey they take is of little value to us. Rather, they appear to be attracted to objects that we discard. In 1929, E.H.Forbush, the indefatigable state ornithologist of Massachusetts – a man who acted as a defence attorney for such accused avians (even though he himself ate some of the species he studied) – noted that a cormorantry off Labrador was embellished with objects the birds had salvaged from shipwrecks, diving like Jane Eyre’s bracelet thief to retrieve penknives, pipes, hairpins and ladies’ combs. Their finds decorated their nests as if they were making their own artistic comments on our disposable culture.