Полная версия

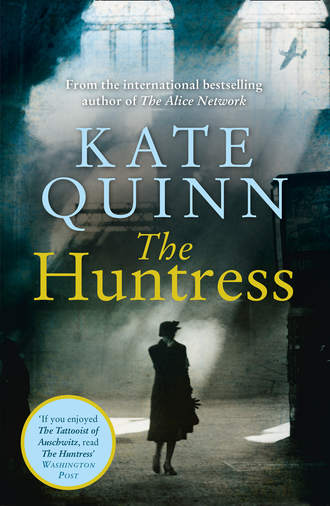

The Huntress

The ice this time of year was thicker than a man was tall, but there were gaps where the ice thinned. The village schoolmaster, less ignorant about the lake than about most of the things he taught, said something about warmer water channels winding upward from the deeper rift, enough to make holes in the surface—and now, her father dragged her across the ice to one of the spring holes, dropped to his knees, broke the thin crust, and thrust her head under the freezing water.

Fear slapped Nina then, alien and spiky as new-forming frost. Even being dragged across the lake by the hair she had not been afraid; it had all happened too fast. But as the dark water swallowed her, terror descended like an avalanche. The water’s cold gripped her; she could see the depths of the lake stretching away below, blue green and fathomless, and she opened her mouth to scream but the lake’s iron fist punched into her mouth with another paralyzing burst of cold.

On the surface, her body thrashed against her father’s grip in her hair. His stone-hard hand thrust her head down deeper, deeper, but she flailed a leg free and slammed one boot into his ribs. He brought her up with a curse, and Nina got one sobbing gasp of air that stabbed her lungs like hot knives. Her father cursed blurrily; he released Nina’s sodden hair and flipped her onto her back, seizing her by the throat instead. “Go back to the lake,” he whispered, “go home.” Again her head went down under the water. This time she could see up through the ripples, up past her father to the twilight sky. Get there, she thought incoherently through another wash of fear, just get up there—and her hand stretched blindly … But it wasn’t the sky her fingers brushed. It was the unfolded razor swinging at her father’s belt.

She couldn’t feel her fingers wrapping around the handle. The cold had her in its jaws, clamping down. But she watched herself move through the ripples of the lake that was drowning her, watched her hand jerk the razor free and bring it around in a savage swipe across her father’s hand. Then he was gone, and Nina came roaring up out of the water, a shard of broken ice on the edge slicing along her throat, but she had the razor in her fist and she was free.

They lay gasping on opposite sides of the ice hole. Her father clutched his hand, which Nina had sliced nearly to the bone, sending curling ribbons of scarlet across the frozen lake. Nina huddled on her side, racked by bone-deep shudders of cold and terror, ice crystals already forming on her lashes and through her hair, a similar ribbon of blood winding down the side of her throat from the ice cut. She still held the razor extended toward her father.

“If you touch me again,” she said through chattering teeth, “I’ll kill you.”

“You’re a rusalka,” he mumbled, looking bewildered at her fury. “The lake won’t hurt you.”

A violent shudder racked her. I am no rusalka, she wanted to scream. I’ll die before I ever let water close over my head again. But all she said was, “I’ll kill you, Papa. Believe it.” And she managed to stumble back to the hut, where she bolted the door, peeled away her ice-crusted clothes, built up the fire, and crawled naked and shuddering under a pile of silver-gray seal pelts. Had it been deep winter the shock of the cold would have killed her, she realized later, but winter’s bite was easing toward spring, and she managed not to die. Her father slept it off in the hunting shack while Nina lay shivering under her furs, still gripping the razor, breaking into hiccuping little sobs whenever she thought of the water lapping over her face, filling her mouth and nose with its iron tang.

I have my one fear, she thought. From that day forward, as far as Nina Markova was concerned, if it wasn’t death by drowning it wasn’t worth being afraid of. Get away from here, she thought, unpeeling from the furs long enough to find her father’s vodka and take several enormous gulps of the oily, peppery stuff. Get out. The thought pounded. Go where? What is the opposite of a lake? What is the opposite of drowning? What lies all the way west? Nonsensical questions. Nina realized she was half drunk. She crawled under the furs again, slept like the dead, and woke with a crust of blood on her throat where the lake’s icy fingers had tried to kill her, and that one clear, cold thought.

Get out.

Chapter 4

JORDAN

April 1946

Boston

Aaaaand it gets away! Line drive past the diving Johnny Pesky—”

“Garrett,” Jordan told her boyfriend as groans rose around them across the stands of Fenway Park, “I know the line drive got past Johnny Pesky. I’m right here, watching the line drive get past Johnny Pesky. You don’t need to give me the play-by-play.”

It was a perfect spring day: the smell of outfield grass, the murmur and rush of the crowd, the scratch of pencils on scorecards. Garrett grinned. “Admit it, you missed our baseball dates when I was in training. Even my play-by-play.” Jordan couldn’t resist raising the Leica for a snap. With his dimples, his broad shoulders, and his Red Sox cap tipped down over short brown hair, Garrett looked about as all-American cute as a Coca-Cola ad. Or a recruitment poster: he’d enlisted at the end of his senior year, giving Jordan his class ring, but a badly broken leg during pilot training and the abrupt end of the war with Japan not long afterward had cut his stint in the army air force very short. She knew Garrett regretted that—he’d been dreaming of dogfights over the Pacific when he signed up, not of being cut loose on a medical discharge before even making it overseas.

“Sure, I missed our baseball dates,” Jordan said playfully. “Maybe not as much as I missed having Ted Williams batting in the three-spot during the war, but—”

Garrett flicked a peanut shell into her ponytail. “Bet I looked better in an army air force uniform than Ted Williams.”

“I’m sure you did, because Ted Williams was a marine.”

“The marines were only invented so the army has someone to take to the prom.”

“I wouldn’t tell any marines that.”

“Too dumb to get the joke.”

The next Yankee came to bat, and Jordan raised the Leica. Only in the darkroom would she know if she missed the high point of the bat’s swing. Flawless timing; every great photographer needed it.

“Come to lunch this Sunday?” Garrett rooted through his bag of peanuts. “My parents are dying to see you.”

“Aren’t they hoping you’ll start dating some Boston University sorority girl in the fall?”

“Come on, you know they love you.”

They did, and so did Garrett, which surprised Jordan. They’d been together since she was a junior, and from the start she’d been determined not to get her heart broken once he moved on. High school seniors went off to college or war, but either way they moved on. And that was just fine, because this business of getting married right after graduation to your high school sweetheart was ridiculous as far as Jordan was concerned (no matter what her dad said about it working perfectly well for him). No, Garrett Byrne would move on to a new girl at some point, and Jordan’s heart was going to be a little bit broken but then she’d toss her head back, sling her Leica around her neck, and go work in European war zones and have affairs with Frenchmen.

But Garrett hadn’t moved on. He’d come back from his medical discharge, still on crutches, and picked up their afternoon baseball dates and Sunday lunches with his parents, who beamed at Jordan as much as her dad beamed at Garrett. The knee-buckling weight of all that parental expectation made everything seem so firm, so settled, that a trip around European war zones taking pictures for LIFE seemed about as likely as a trip to the moon.

“C’mon.” Garrett sneaked an arm around her waist, nuzzled her ear in that way that also made her knees buckle. “Sunday lunch. We can go for a drive afterward, park somewhere …”

“I can’t,” Jordan said, regretful. “Mass with Dad and Mrs. Weber.”

“It must be serious.” Garrett grinned again. “So, how is this Fräulein of your father’s?”

“She’s very nice.” There had been another dinner, this time at Anneliese Weber’s tiny spotless apartment; she had been warm and welcoming, and made crisp fried schnitzel and some kind of pink-iced Austrian cake soaked in rum. Jordan’s father had gone all soft around the edges as Anneliese served him, and Jordan already adored little Ruth, who had asked in a whispery voice how der Hund was. It had all been fine, absolutely fine.

Jordan didn’t know why, but she kept thinking back to that picture. Anneliese Weber looking by a strange twist of light and lens to be about as soft and welcoming as a straight razor.

“She’s very nice,” Jordan said again. The Sox went down 4–2, and soon Jordan and Garrett were streaming out of Fenway with the rest of the fans, crunching peanut shells and discarded scorecards underfoot. “It’s our year,” Jordan proclaimed. “This year we win it all, I can feel it. Walk me to the shop? I promised Dad I’d swing by.”

Hand in hand, they made their way through the game crowd and finally turned onto Commonwealth, Jordan stretching her steps to match Garrett’s, who still walked with a slight limp. It was that day, she thought, the sudden spring day coming at the end of a too-long winter. As they turned down the central mall on Commonwealth, it seemed like all Boston had tossed their heavy coats and come outside, winter-pale faces blissfully skyward as they stumbled along absolutely drunk on the warmth. It was why Jordan loved Boston—there was something about its citizens that was curiously welded together, more like a small town than a big city. Everyone seemed to know everyone else, their heartaches and their secrets … And that brought a frown to Jordan’s face.

“I wish I knew more about her,” she heard herself say.

“Who?” Garrett had been talking about the classes he’d take in the fall.

“Mrs. Weber.” Jordan fiddled with the Leica’s strap.

“What do you want to know?” Garrett asked reasonably. They were passing the Hotel Vendome, and Jordan nearly stepped in front of a Chevrolet coupe. Garrett pulled her back. “Careful—”

“That,” Jordan said. “She’s careful. She doesn’t say much about herself. And I caught the strangest expression on her face when I took her picture …”

Garrett laughed. “You don’t take a dislike to someone just because of a funny expression.”

“Girls do it all the time. Sometimes you catch a boy looking at you in the hall at school, when he thinks you can’t see him. I don’t mean looking at girls the way all boys do,” Jordan clarified. “I mean looking at you in a way that gives you the shivers. He doesn’t mean for you to see, and maybe that expression only lasts a second, but it’s enough to make you think, I don’t want to be alone with you.”

“Girls think that?” Garrett sounded mystified.

“I don’t know a single girl who hasn’t had that thought,” Jordan stated. “I’m just saying, sometimes you catch the wrong look on someone’s face and it puts you off. It makes you not want to take chances, getting to know them.”

“But this isn’t a boy leering around the locker door at school. It’s a woman your father is inviting home to dinner. You have to give her a chance.”

“I know.”

“Your dad’s really serious about her.” Garrett tweaked Jordan’s ponytail. “Maybe that’s the whole problem.”

“I am not jealous,” Jordan flashed. Then amended, “All right, maybe I am. A tiny, tiny bit. But I want Dad happy, I do. And Mrs. Weber is good for him. I can see that. But before I trust her with my father, I want to know more about her.”

“So just ask her.”

McBride’s Antiques sat on the corner of Newbury and Clarendon—not the best shopping district in Boston, but distinguished enough. Every morning, as long as Jordan could remember, her father had walked the three miles from their home to the shop that had been his father’s, mounting those worn stone steps toward the door with its ancient bronze knocker, unlocking the shutters to unveil the big giltlettered window. Jordan frowned at the window display as it came into view today, seeing that the tasseled lamps and Victorian hatstand from yesterday had been swapped for a tailor’s dummy in a wedding dress of antique lace, and a display of cabochon rings sparkling on a velvet tray. Jordan mounted the steps ahead of Garrett, hearing the sweet tinkle of the bell as she pushed the door open. She wasn’t really surprised to see her father beside the long counter, holding Anneliese Weber’s hand with a proprietary air. “I’ve got wonderful news, missy!”

Jordan couldn’t describe the mix of emotions that rose in her—why her heart squeezed in honest pleasure, seeing the happiness on her father’s face as he looked down at the Austrian widow’s left hand with its cluster of antique garnets and pearls … and why at the same time her stomach tightened as she came to give her soon-to-be stepmother a hug.

JUST ASK HER, Garrett had said. Jordan got her chance two days later, when Mrs. Weber invited her to go shopping for wedding clothes after she came home from school. As they sallied down Boylston Street, Jordan was still trying to find a casual segue into the questions she wanted to ask when Mrs. Weber took the initiative.

“Jordan, I hope you don’t feel you must call me—well, not Mutti, I suppose for you it would be Mother or Mama.” A smile at Jordan’s expression. “At your age that seems silly.”

“A little.”

“Well, you certainly don’t have to call me either. I don’t mean to take the place of your mother. Your father has told me about her, and she sounds like a lovely woman.”

“I don’t remember her very well.” Just her absence once she got sick, really. And all the reasons why, which they wouldn’t tell me, so I made them up for myself. Jordan wished she remembered more than that. She looked sideways at Anneliese, gliding along in her blue spring coat, pocketbook in gloved hands, heels hardly clicking on the sidewalk. Jordan felt large and clumping beside her, naked without her camera.

“I thought we’d go to Priscilla of Boston,” Anneliese suggested. “Usually I make up my own clothes, but for a wedding one needs something special. I don’t know if your father discussed the plans with you, men can be so vague about wedding details. We thought a quiet day wedding three weeks from now, just the four of us at the chapel and a few of your father’s friends.”

“And on your side?”

“No one. I haven’t been in Boston long enough to make friends.”

“Really?” For a woman who’d said she was trying so hard to make friends in a new country—and whose English was so good—it seemed odd. “Not even a next-door neighbor, or someone at the beauty shop, or another mother at the park?”

“I find it hard, talking with strangers.” A tentative smile. “I hoped you would be my maid of honor?”

“Of course.” Though Jordan couldn’t stop wondering. Months in Boston, and you don’t have one single acquaintance?

“Your father and I planned for a honeymoon weekend in Concord,” Anneliese continued, “if you could watch Ruth.”

“Of course.” Jordan’s smile was unforced this time. “Ruth’s a darling. I love her already.”

“She has that effect on people,” Anneliese agreed.

Jordan took a silent breath. “Does she get that beautiful fair hair from her father?”

A pause. “Yes, she does.”

“What did you say his name was—Kurt?”

“Yes. What color do you fancy wearing for the wedding?” Anneliese turned through the doors of the boutique, moving through the ivory bridal gowns and floral bridesmaid dresses, waving away salesgirls. “This blue? So lovely with your skin.”

She took off her gloves to test the fabric between her fingertips, and Jordan eyed her hands, naked of rings except for the engagement cluster of garnets. She tried to remember if she’d ever seen Anneliese wearing a wedding ring and was certain she had not. “You could wear your old ring, you know,” she threw out, trying a new tack.

Anneliese looked startled. “What?”

“Dad would never mind if you kept wearing your husband’s ring. He was a part of your life—I hope you don’t feel we expect you to forget him.”

“Kurt never gave me a wedding ring.”

“Is it not customary in Austria?”

“No, it was, he—” Anneliese sounded almost flustered for a moment. “We were rather poor, that’s all.”

Or maybe you lied about being married, Jordan couldn’t stop herself thinking. Maybe it’s not the only thing you’ve lied about either …

Her father’s voice, scolding: Wild stories.

“I think you’re right about this dress.” Jordan looked at the pale blue frock, full skirted and simple. “Ruth would look pretty in blue too, with her dark eyes. Most blondes have blue eyes like yours. She must have gotten her eyes from her father too.”

“Yes.” Anneliese fingered the sleeve of a pale pink suit, face smooth again.

“Well, it’s very striking.” Jordan tried to think where to tug the discussion next. It wasn’t just Ruth or Anneliese’s first husband she was interested in, it was everything—but something about the wedding ring had jarred Anneliese’s poise. “Did Ruth ever know her father, or—”

“No, she doesn’t remember him. He was very handsome, though. So is your young man. Would you like to bring Garrett to the wedding?”

“He’ll be working if it’s a day wedding—he’s putting in hours for his father’s boss until he starts at Boston University in the fall. His parents want him to join the business, though all he wants to do now is fly planes. Garrett never saw combat; he broke his leg too badly during training, and the war ended before he was anywhere near healed, so he was discharged early. Was your husband in the war?”

“Yes.” Anneliese picked up a cream straw hat, examining its blue ribbon. Jordan tried a question about Anneliese’s family next, but she didn’t seem to hear it. “Do you plan to follow Garrett to Boston University this fall?” she asked instead.

“Well—” Jordan blinked, sidetracked. “I’d like to, but Dad isn’t keen. With a business in the family, he doesn’t think college is necessary.” Especially for a girl. “He never went, and always says he didn’t regret it.”

“I’m sure he didn’t. But you have your own path, like any young person. Perhaps we might try to change his mind, you and I. Even the best men sometimes require steering.” Anneliese gave a conspiratorial smile, perching the hat on Jordan’s head. “That’s lovely. Why don’t you try on the dress? For myself, I think this pink suit …”

Jordan slipped into a changing cubicle, diverted despite herself. She’d first thought of a stepmother as something wonderful for her father and his loneliness—then, given all she didn’t know about this woman and her life even as she moved into theirs, as something to be uneasy about. It had never occurred to Jordan to think a stepmother could be … well, an ally. Perhaps we might try to change his mind, you and I. That made Jordan smile as she fastened up the blue dress with its snug waist and swirl of skirt, hearing the rustle of clothing as Anneliese changed on the other side of the wall. Did you mean it? Jordan wondered. Or were you trying to derail me from asking about you?

“Beautiful,” Anneliese approved as Jordan came out. “Against that blue, your skin is pure American peaches and cream.”

“You look lovely too,” Jordan said honestly. Petite and elegant in a suit the color of baby roses, Anneliese revolved before the triple mirror. An assistant fluttered with pins, and Jordan moved closer, straightening Anneliese’s sleeve. “Would you really help me with Dad, changing his mind about college? Most people tell me it’s a silly thing to want, when I’ve got a nice boyfriend and a place in the shop waiting for me, and I’m already working the counter on weekends.”

“Nonsense.” Anneliese smoothed the jacket over her waist. “Clever girls like you—another dart here?—should be encouraged to want more, not less.”

“Did you, at my age?” Jordan couldn’t help the question that popped out next. “You said you went to college. Where was that?”

Anneliese’s blue eyes met hers in the mirror for a thoughtful moment. “You don’t entirely trust me, Jordan,” she said at last in her very-faintly-accented English. “No, don’t protest. It’s quite all right. You love your father; you want the best for him. So do I.”

“It’s not that I—” Jordan felt her cheeks flame. Why do you have to probe things? she chastised herself. Why can’t you just flutter and squeal like a normal girl in a bridal shop? “I don’t distrust you—I just don’t know you, and …”

Anneliese let her struggle into silence. “I’m not easy to know,” she said at last. “The war was difficult for me. I don’t enjoy talking about it. And we Germans are more reserved than Americans even at the best of times.”

“I thought you were Austrian,” Jordan said before she could stop herself.

“I am.” Anneliese turned to examine the skirt hem in the mirror. “But I went to Heidelberg as a young girl—for university, to answer your question. I studied English there and met my husband.” A smile. “Now you know something more about me, so shall we make our purchase and look for a dress for Ruth? There’s a children’s boutique not far away.”

Jordan’s cheeks stayed hot as they left the shop with their parcels. I am a worm, she thought, kicking herself, but Anneliese seemed to hold no grudge, swinging her handbag and tilting her nose up to the breeze. “My former husband would say this is hunting weather,” she exclaimed, reminiscent. “I’m no good at hunting, but I always did like heading to the woods on such days. Spring breezes bringing every scent right to your nose …”

Jordan wondered why her stomach had tightened again, when Anneliese was chatting away in a perfectly forthcoming fashion. Because you’re jealous, she told herself witheringly. Because you don’t want to share your father, and you resent her for it. That’s a mean, nasty little feeling to have, Jordan McBride. And you’re going to get over it, right now.

Chapter 5

IAN

April 1950

Vienna

You have a wife?” Tony dragged Ian into the corner for a quick, hissed discussion. “Since when?”

Ian contemplated the woman now sitting at his desk, boots propped on the blotter, crunching down biscuits straight from the tin. “It’s complicated,” he said eventually.

“No, it isn’t. At some point you and this woman stood up together and said a lot of stuff about to have and to hold, and there was an I do. It’s pretty definitive. And why didn’t you tell me four days ago when I said she was coming here? Did you just forget?”

“Call it a sadly misplaced impulse to have a joke at your expense.”

Tony glowered. “Was the part about her being such a fragile flower a joke too?”

No, that turned out to be a joke on me. Ian remembered Nina stumbling over the foreign words of the marriage service, swaying on her feet from weakness. The entire wedding had taken less than ten minutes: Ian had rushed through his own vows, pushed his signet ring onto Nina’s fourth finger where it hung like a hoop, taken her back to her hospital bed, and promptly headed off to fill out paperwork and finish a column on the occupation of Poznań. Now, five years later, he watched Nina suck biscuit crumbs off her fingertip and saw she was still wearing the ring. It fit much better. “I came across Nina in Poznań after the German retreat,” Ian said, realizing his partner was waiting for answers. “The Polish Red Cross picked her up half dead from double pneumonia. She’d been living rough in the woods after her run-in with die Jägerin. She looked like a stiff breeze would kill her.”