Полная версия

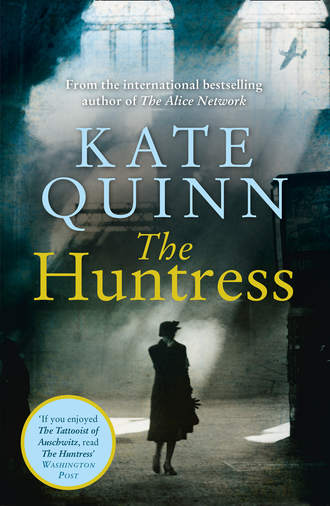

The Huntress

“It wasn’t nearly as picturesque as you make it sound.”

“So? Talk it up! You’ve got glamour, boss. Women love ’em tall, dark, and tragic. You’re six long-lean-and-mean feet of heroic war stories and unhappy past—”

“Oh, for God’s sake—”

“—all buttoned up behind English starch and a thousand-yard stare of you can’t possibly understand the things that haunt me. That’s absolute catnip for the ladies, believe me—”

“Are you finished?” Ian drew the sheet out of the typewriter, tipping his chair back on two legs. “Go through the mail, then pull the file on the Bormann assistant.”

“Fine, die a monk.”

“Why do I put up with you?” Ian wondered. “Feckless cretinous Yank …”

“Joyless Limey bastard,” Tony shot back, rummaging in the file cabinet. Ian hid a grin, knowing perfectly well why he put up with Tony. Ranging across three fronts of the war with a typewriter and notepad, Ian had met a thousand Tonys: achingly young men in rumpled uniforms, heading off into the mouth of the guns. American boys jammed on troopships and green with seasickness, English boys flying off in Hurricanes with a one in four chance of making it back … after a while Ian couldn’t bear to look at any of them too closely, knowing better than they did what their chances were of getting out alive. It had been just after the war ended that he met Tony, slouching along as an interpreter in the entourage of an American general who clearly wanted him court-martialed and shot for insubordination and slovenliness. Ian sympathized with the feeling now that Sergeant A. Rodomovsky worked for him and not the United States Army, but Tony was the first young soldier Ian had been able to befriend. He was brash, a practical joker, and a complete nuisance, but when Ian shook his hand for the first time, he’d been able to think, This one won’t die.

Unless I kill him, Ian thought now, next time he gets on my nerves. A distinct possibility.

He finished the report for Bauer and rose, stretching. “Get your earplugs,” he advised, reaching for his violin case.

“You’re aware you don’t have a future as a concert violinist?” Tony leafed through the stack of mail that had accumulated in their absence.

“I play poorly yet with great lack of feeling.” Ian brought the violin to his chin, starting a movement of Brahms. Playing helped him think, kept his hands busy as his brain sorted through the questions that rose with every new chase. Who are you, what did you do, and where would you go to get away from it? He was drawing out the last note as Tony let out a whistle.

“Boss,” he called over his shoulder, “I’ve got news.”

Ian lowered his bow. “New lead?”

“Yes.” Tony’s eyes sparked triumph. “Die Jägerin.”

A trapdoor opened in Ian’s stomach, a long drop over the bottomless pit of rage. He put the violin back in its case, slow controlled movements. “I didn’t give you that file.”

“It’s the one at the back of the drawer you look at when you think I’m not paying attention,” Tony said. “Believe me, I’ve read it.”

“Then you know it’s a cold trail. We know she was in Poznań as late as November ’44, but that’s all.” Ian felt excitement starting to war with caution. “So what did you find?”

Tony grinned. “A witness who saw her later than November ’44. After the war, in fact.”

“What?” Ian had been pulling out his file on the woman who was his personal obsession; he nearly dropped it. “Who? Someone from the Poznań region, or Frank’s staff?” It had been during the first Nuremberg trial that Ian caught die Jägerin’s scent, hearing a witness testify against Hans Frank—the governor general of Nazi-occupied Poland, whom Ian would later (as one of the few journalists admitted to the execution room) watch swing from a rope for war crimes. In the middle of the information about the Jews Frank was shipping east, the clerk had testified about a certain visit to Poznań. One of the high-ranking SS officers had thrown a party for Frank out by Lake Rusalka, at a big ocher-colored house …

Ian, at that point, had already had a very good reason to be searching for the woman who had lived in that house. And the clerk on the witness stand had been a guest at that party, where the SS officer’s young mistress had played hostess.

“Who did you find?” Ian rapped out at Tony, mouth dry with sudden hope. “Someone who remembers her? A name, a bloody photograph—” It was the most frustrating dead end of this file: the clerk at Nuremberg had met the woman only once, and he’d been drunk through most of the party. He didn’t remember her name, and all he could describe was a young woman, dark haired, blue eyed. Difficult to track a woman without knowing anything more than her nickname and her coloring. “What did you find?”

“Stop cutting me off, dammit, and I’ll tell you.” Tony tapped the file. “Die Jägerin’s lover fled to Altaussee in ’45. No sign he took his mistress with him from Poznań—but now, it’s looking like he did. Because I’ve located a girl in Altaussee whose sister worked a few doors down from the same house where our huntress’s lover had holed up with the Eichmanns and the rest of that crowd in May ’45. I haven’t met the sister yet, but she apparently remembers a woman who looked like die Jägerin.”

“That’s all?” Ian’s burst of hope ebbed as he recalled the pretty little spa town on a blue-green lake below the Alps, a bolt-hole for any number of high-ranking Nazis as the war ended. By May ’45 it had been crawling with Americans making arrests. Some fugitives submitted to handcuffs, some managed to escape. Die Jägerin’s SS officer had died in a hail of bullets rather than be taken—and there had been no sign of his mistress. “I’ve already combed Altaussee looking for leads. Once I knew her lover had died there, I went looking—if she’d been there too, I would have found her trail.”

“Look, you probably came on like some Hound of Hell from the Spanish Inquisition, and everyone clammed up in terror. Subtlety is not your strong suit. You come on like a wrecking ball that went to Eton.”

“Harrow.”

“Same thing.” Tony fished for his cigarettes. “I’ve been doing some lighter digging. All that driving around Austria we did last December, looking for the Belsen guard who turned out to have gone to Argentina? I took weekends, went to Altaussee, asked questions. I’m good at that.”

He was. Tony could talk to anyone, usually in their native language. It was what made him good at this job, which so often hinged on information eased lightly out of the suspicious and the wary. “Why did you put in all this effort on your own time?” Ian asked. “A cold case—”

“Because it’s the case you want. She’s your white whale. All these bastards”—Tony waved a hand at the filing cabinets crammed with documentation on war criminals—“you want to nab them all, but the one you really want is her.”

He wasn’t wrong. Ian felt his fingers tighten on the edge of the desk. “White whale,” he managed to say, wryly. “Don’t tell me you’ve read Melville?”

“Of course not. Nobody’s read Moby-Dick; it just gets assigned by overzealous teachers. I went to a recruiter’s office the day after Pearl Harbor; that’s how I got out of reading Moby-Dick.” Tony shook out a cigarette, black eyes unblinking. “What I want to know is, why die Jägerin?”

“You’ve read her file,” Ian parried.

“Oh, she’s a nasty piece of work, I’m not arguing that. That business about the six refugees she killed after feeding them a meal—”

“Children,” Ian said quietly. “Six Polish children, somewhere between the ages of four and nine.”

Tony stopped in the act of lighting his cigarette, visibly sickened. “Your clipping just said refugees.”

“My editor considered the detail too gruesome to include in the article. But they were children, Tony.” That had been one of the harder articles Ian had ever forced himself to write. “The clerk at Frank’s trial said that, at the party where he met her, someone told the story about how she’d dispatched six children who had probably escaped being shipped east. An amusing little anecdote over hors d’oeuvres. They toasted her with champagne, calling her the huntress.”

“Goddamn,” Tony said, very softly.

Ian nodded, thinking not only of the six unknown children who had been her victims, but of two others. A fragile young woman in a hospital bed, all starved eyes and grief. A boy just seventeen years old, saying eagerly I told them I was twenty-one, I ship out next week! The woman and the boy, one gone now, the other dead. You did that, Ian thought to the nameless huntress who filled up his sleepless nights. You did that, you Nazi bitch.

Tony didn’t know about them, the girl and the young soldier. Even now, years later, Ian found it difficult. He started marshaling the words, but Tony was already scribbling an address, moving from discussion to action. For now, Ian let it go, fingers easing their death grip on the desk’s edge.

“That’s where the girl in Altaussee lives, the one whose sister might have seen die Jägerin,” Tony was saying. “I say it’s worth going to talk in person.”

Ian nodded. Any lead was worth running down. “When did you get her name?”

“A week ago.”

“Bloody hell, a week?”

“We had the Cologne chase to wrap up. Besides, I was waiting for one more confirmation. I wanted to give you more good news, and now I can.” Tony tapped the letter from their mail stack, scattering ash from his cigarette. “It arrived while we were in Cologne.”

Ian scanned the letter, not recognizing the black scrawl. “Who’s this woman and why is she coming to Vienna …” He got to the signature at the bottom, and the world stopped in its tracks.

“Our one witness who actually met die Jägerin face-to-face and lived,” Tony said. “The Polish woman—I pulled her statement and details from the file.”

“She emigrated to England, why did you—”

“The telephone number was noted. I left a message. Now she’s coming to Vienna.”

“You really shouldn’t have contacted Nina,” Ian said quietly.

“Why not? Besides this potential Altaussee lead, she’s the only eyewitness we’ve got. Where’d you find her, anyway?”

“In Poznań after the German retreat in ’45. She was in hospital when she gave me her statement, with all the details she could remember.” Vividly Ian recalled the frail girl in the ward cot, limbs showing sticklike from a smock borrowed from the Polish Red Cross. “You shouldn’t have dragged her halfway across Europe.”

“It was her idea. I only wanted to talk by telephone, see if I could get any more detail about our mark. But if she’s willing to come here, let’s make use of her.”

“She also happens to be—”

“What?”

Ian paused. His surprise and disquiet were fading, replaced by an unexpected flash of devilry. He so rarely got to see his partner nonplussed. You spring a surprise like this on me, Ian thought, you deserve to have one sprung on you. Ian wouldn’t have chosen to yank the broken flower that was Nina Markova halfway across the continent, but she was already on the way, and there was no denying her presence would be useful for any number of reasons … including turning the tables on Tony, which Ian wasn’t too proud to admit he enjoyed doing. Especially when his partner started messing about with cases behind Ian’s back. Especially this case.

“She’s what?” Tony asked.

“Nothing,” Ian answered. Aside from pulling the ground out from under Tony, it might be good to see Nina. They did have matters to discuss that had nothing to do with the case, after all. “Just handle her carefully when she arrives,” he added, that part nothing but truthful. “She had a bad war.”

“I’ll be gentle as a lamb.”

FOUR DAYS PASSED, and a flood of refugee testimony came in that needed categorizing. Ian forgot all about their coming visitor, until an unholy screeching sounded in the corridor.

Tony looked up from the statement he was translating from Yiddish. “Our landlady getting her feathers ruffled again?” he said as Ian went to the office door.

His view down the corridor was blocked by Frau Hummel’s impressive bulk in her flowered housedress, as she pointed to some muddy footprints on her floor. Ian got a bare impression of a considerably smaller woman beyond his landlady, and then Frau Hummel seized the mud-shod newcomer by the arm. Her bellows turned to shrieks as the smaller woman yanked a straight razor out of her boot and whipped it up in unmistakable warning. The newcomer’s face was obscured by a tangle of bright blond hair; all Ian could really take in was the razor held in an appallingly determined fist.

“Ladies, please!” Tony tumbled into the hall.

“Kraut suka said she’d call police on me—” The newcomer was snarling.

“Big misunderstanding,” Tony said brightly, backing Frau Hummel away and waving the strange woman toward Ian. “If you’ll direct your concerns to my partner here, Fräulein—”

“This way.” Ian motioned her toward his door, keeping a wary eye on the razor. Rarely did visitors enter quite this dramatically. “You have business with the Refugee Documentation Center, Fräulein?”

The woman folded up that lethally sharp razor and tucked it back into her boot. “Arrived an hour less ago,” she said in hodgepodge English as Ian closed the office door. Her accent was strange, somewhere between English and something farther east than Vienna. It wasn’t until she straightened and brushed her tangled hair from a pair of bright blue eyes that Ian’s heart started to pound.

“Still don’t know me from Tom, Dick, or Ivan?” she asked.

Bloody hell, Ian thought, frozen. She’s changed.

Five years ago she’d lain half starved in a Red Cross hospital bed, all brittle silence and big blue eyes. Now she looked capable and compact in scuffed trousers and knee boots, swinging a disreputable-looking sealskin cap in one hand. The hair he remembered as dull brown was bright blond with dark roots, and her eyes had a cheery, wicked glitter.

Ian forced the words through numb lips. “Hello, Nina.”

Tony came banging back in. “The gnädige Frau’s feathers are duly smoothed down.” He gave Nina a rather appreciative glance. “Who’s our visitor?”

She looked annoyed. “I sent a letter. You didn’t get?” Her English has improved, Ian thought. Five years ago they’d barely been able to converse; she spoke almost no English and he almost no Polish. Their communication in between then and now had been strictly by telegram. His heart was still thudding. This was Nina …?

“So you’re—” Tony looked puzzled, doubtless thinking of Ian’s description of a woman who needed gentle handling. “You aren’t quite what I was expecting, Miss Markova.”

“Not Miss Markova.” Ian raked a hand through his hair, wishing he’d explained it all four days ago, wishing he hadn’t had the impulse to turn the tables on his partner. Because if anyone in this room had had the tables turned on them, it was Ian. Bloody hell. “The file still lists her birth name. Tony Rodomovsky, allow me to introduce Nina Graham.” The woman in the hospital bed, the woman who had seen die Jägerin face-to-face and lived, the woman now standing in the same room with him for the first time in five years, a razor in her boot and a cool smile on her lips. “My wife.”

Chapter 3

NINA

Before the war

Lake Baikal, Siberia

She was born of lake water and madness.

To have the lake in her blood, that was to be expected. They all did, anyone born on the shore of Baikal, the vast rift lake at the eastern edge of the world. Any baby who came into the world beside that huge lake lying like a second sky across the taiga knew the iron tang of lake water before they ever knew the taste of mother’s milk. But Nina Borisovna Markova’s blood was banded with madness, like the deep striations of winter lake ice. Because the Markovs were all madmen, everyone knew that—every one of them swaggering and wild-eyed and savage as wolverines.

“I breed lunatics,” Nina’s father said when he was deep into the vodka he brewed in his hunting shack behind the house. “My sons are all criminals and my daughters are all whores—” and he’d lay about him with huge grimed fists, and his children hissed and darted out of the way like sharp-clawed little animals, and Nina might get an extra clout because she was the only tiny blue-eyed one in a litter of tall dark-eyed sisters and taller dark-eyed brothers. Her father’s gaze narrowed whenever he looked at her. “Your mother was a rusalka,” he’d growl, huddled in his shirt half covered by a clotted black beard.

“What’s a rusalka?” Nina finally asked at ten.

“A lake witch who comes to shore trailing her long green hair, luring men to their deaths,” her father replied, dealing a blow Nina ducked with liquid speed. It was the first thing a Markov child learned, to duck. Then you learned to steal, scrabbling for your own portion of watery borscht and hard bread, because no one shared, not ever. Then you learned to fight—when the other village boys were learning to net fish and hunt seals, and the girls were learning to cook and mend fishing nets, the Markov boys learned to fight and drink, and the Markova girls learned to fight and screw. That led to the last thing they learned, which was to leave.

“Get a man who will take you away,” Nina’s next-oldest sister told her. Olga was gathering her clothes: fifteen, her body rounding, eyes already trained west in the direction of Irkutsk, the nearest city, hours away beyond the Siberian horizon. Nina couldn’t imagine what a city looked like. All she’d ever seen was the collection of ramshackle huts that could barely be called a village; fishing boats silvery and pungent with fish scales; the endless spread of the lake. “Get a man,” Olga repeated, “because that’s the only way you’ll get out.”

“I’ll find a different way,” Nina said. Olga gave her a spiteful scratch in farewell and was gone. None of Nina’s siblings ever came back; it was everyone for themselves, and she didn’t miss them until the last brother left, and it was just her and her father. “Little rusalka bitch”—he slung Nina around the hut as she hissed and scratched at the huge hand tangled in her wild hair—“I should give you back to the lake.” He didn’t frighten Nina much. Weren’t all fathers like hers? He loomed as large in her world as the lake. In a way, he was the lake. The villagers sometimes called the lake “the Old Man.” One Old Man stretched blue and rippling on the doorstep, and the other old man banged her around the hut.

He wasn’t always wild. In mellow moods he sang old songs of Father Frost and Baba Yaga, stropping the straight razor that always swung at his belt. In those moods he’d show Nina how to tan a pelt from the seals he shot with the ancient rifle over the door; took her hunting with him and taught her how to move over the snow in perfect silence. Then he didn’t call her a rusalka; he tugged her ear and called her a little huntress. “If I teach you anything,” he whispered, “let it be how to move through the world without making a sound, Nina Borisovna. If they can’t hear you coming, they’ll never lay hands on you. They haven’t caught me yet.”

“Who, Papa?”

“Stalin’s men,” he spat. “The ones who stand you against a wall and shoot you for saying the truth—that Comrade Stalin is a lying, murdering pig who shits on the common man. They kill you for saying things like that, but only if they can find you. So keep silent feet and they’ll never hunt you down. You’ll hunt them down instead.”

He’d go on like that for hours, until Nina dozed off. Comrade Stalin is a Georgian swine, Comrade Stalin is a murdering sack of shit. “Stop him saying those things,” the old women who bartered clothes whispered to Nina when she came to trade. “We’re not so far out on the edge of the world that the wrong ears can’t hear us. That father of yours will get himself shot, and his neighbors.”

“He says the tsar was a murdering sack of shit too,” Nina pointed out. “And Jews, and the natives, and any seal hunters who leave carcasses on our section of shore. He thinks everything and everyone is shit.”

“It’s different to say it about Comrade Stalin!”

Nina shrugged. She wasn’t afraid of anything. It was another curse in the Markov family; none of them feared blood or darkness or even the legend of Baba Yaga hiding in the trees. “Baba Yaga is afraid of me,” Nina said to another village child when they were scrapping ferociously over a broken doll. “You’d better be afraid of me too.” She got the doll, thrust at her by the child’s mother who crossed herself in the old way, the way the people did before they learned that religion was the opiate of the masses.

“Fearlessness, heh,” Nina’s father said when he heard. “It’s why my children will all die before me. You fear nothing, you get stupid. It’s better to fear one thing, Nina Borisovna. Put all the terror into that, and it leaves you just careful enough.”

Nina looked at her father wonderingly. He was so enormous, wild as a wolf; she could not imagine him afraid of anything. “What’s your fear, Papa?”

He put his lips to her ear. “Comrade Stalin. Why else live on a lake the size of the sea, as far east in the world as you can go before falling off?”

“What’s as far west as you can go before falling off?” The sun went west to die, and most of the world was west of here, but beyond that Nina hardly knew. There was only one schoolmaster in the village, and he was almost as ignorant as the children he taught. “What’s all the way west?”

“America?” Nina’s father shrugged. “Godless devils. Worse than Stalin. Stay clear of Americans.”

“They’ll never catch me.” Tapping her toes. “Silent feet.”

He toasted that with a swallow of vodka and one of his rare knife-edged smiles. A good day. His good days always came back to bad ones, but that never bothered her because she was fast and silent and feared nothing, and she could always keep out of reach.

Until the day she turned sixteen, when her father tried to drown her in the lake.

Nina was standing on the shore in a pure, cold twilight. The lake was frozen in a sheet of dark green glass, so clear you could see the bottom far below. When the surface ice warmed during the day, crevasses would open, crackling and booming as if the lake’s rusalki were fighting a war in the depths. Close to shore, hummocks of turquoise-colored ice heaved up over each other in blocks taller than Nina, shoved onto the bank by the winter wind. A few years ago, those frozen waves had crawled so far ashore that Tankhoy Station had been entirely swallowed in wind-flung blue ice. Nina stood in her shabby winter coat, hands thrust into her pockets, wondering if she would still be here to see the lake freeze next year. She was sixteen years old; all her sisters had left home before they reached that age, mostly with swelling bellies. All the same, Markov’s daughters, came the whisper in the village. They all go bad.

“I don’t care if I go bad,” Nina said aloud. “I just don’t want a big belly.” But there didn’t seem to be anything else her father’s daughters did, except grow up, start breeding, and run away. Nina kicked restlessly at the shore, and her father came lurching out of the hut, naked to the waist, oblivious to the cold. Clumsy inked dragons and serpents writhed over his arms, and his body steamed. He’d been on one of his binges, guzzling vodka and muttering mad things for days, but now he seemed lucid again. He gazed at her, seeing her for the first time all day, and his eyes had an odd gleam. “The Old Man wants you back,” he said conversationally.

And he was after her like a wolf, though Nina got three sprinting strides toward the trees before the huge hand snatched at her hair and yanked her off her feet. She hit the ground so hard the world slipped sideways, and when it came to rights she was on her back, boots scrabbling on the ground as her father dragged her onto the glass-smooth lake.