Полная версия

The Children of Freedom

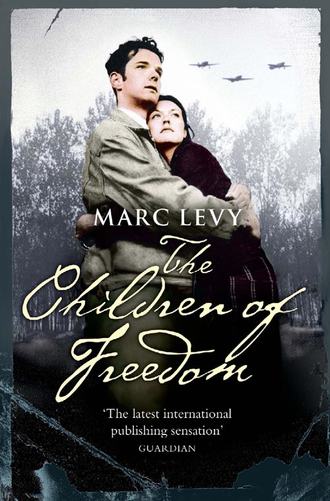

The Children of Freedom

Translated from the French by Sue Dyson

Marc Levy

For my father for his brother Claude, for all the children of freedom.

For my son and for you my love.

I am very fond of that verb, ‘to resist’. To resist what imprisons us, to resist prejudices, hasty judgements, the desire to judge, everything that is bad in us and cries out to be expressed, the desire to abandon, the need to make people feel sorry for us, the need to talk about ourselves to the detriment of others, fashions, unhealthy ambitions, prevailing confusion.

To resist, and…to smile.

Emma Dancourt

Table of Contents

Cover Page

Title Page

Epigraph

Prologue

PART ONE

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

PART TWO

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

PART THREE

30

31

32

33

34

35

36

37

38

39

Epilogue

About the Author

Also by Marc Levy

Copyright

About the Publisher

Prologue

Tomorrow I shall love you; today I don’t yet know you. I began by walking down the staircase of the old apartment building where I lived, a little hurriedly, I confess. On the ground floor, my hand gripped the handrail and felt the beeswax that the concierge applied methodically as far as the bend on the second-floor landing on Mondays, and then up to the other floors on Thursdays. Although light was gilding the fronts of the buildings, the pavement was still glistening from the dawn rain. Just think: as I walked along lightly, I as yet knew nothing, nothing at all about you, you who would one day assuredly give me the most beautiful gift that life gives to human beings.

I went into the little café on rue Saint-Paul; I had time on my hands. There were only three people at the counter – not many of us had an abundance of leisure on that spring morning. And then, hands behind his raincoat, my father came in. He rested his elbows on the bar-top as if he hadn’t seen me, an elegant mannerism that was all his own. He ordered a strong coffee and I caught sight of the smile he was hiding from me as well as he could, which wasn’t that good. He tapped on the counter, signalling to me that ‘all was quiet’ and I could at last approach. As I brushed against his jacket, I felt his strength, the weight of the sadness crushing his shoulders. He asked me if I was ‘still sure’. I wasn’t sure of anything, but I nodded. Then he pushed his cup towards me very discreetly. Underneath the saucer was a fifty-franc note. I refused it, but he set his jaw very firmly and muttered that in order to make war, one had to have a full belly. I took the banknote and, from the look he gave me, I realised that it was time for me to leave. I adjusted my cap, opened the café door and walked back up the street.

Walking past the window, I looked at my father inside the bar, a little stolen glance, that’s all; and he gave me his final smile, to indicate to me that my collar wasn’t on straight.

There was a look of urgency in his eyes that it took me years to understand, but all I have to do today is close mine and think of him for his last expression to come back to me, intact. I know that my father was sad that I was leaving, and I guess also that he sensed that we would never see each other again. It wasn’t his death he was envisaging, but mine.

I think back to that moment in the Café des Tourneurs. It must demand a lot of courage on the part of a man to bury his son while standing right next to him, drinking a chicory-blend coffee, to remain silent and not say to him, ‘Go home right now and do your homework’.

One year earlier, my mother had gone to fetch our yellow stars from the police station. This was the signal for our exodus and we left for Toulouse. My father was a tailor and he would never sew that filth on a piece of fabric.

On that day, 21 March 1943, I was eighteen years old. I caught the tram and I left for a station that doesn’t feature on any map: I went to seek out the Maquis.

Ten minutes ago I was still called Raymond; since I got off at the terminus of line 12, my name is Jeannot. Nameless Jeannot. At that still-gentle time of day, many people in my world have no idea what is going to happen to them. Dad and Mum don’t know that soon a number is going to be tattooed on their arms; Mum doesn’t know that on a railway platform, she will be separated from this man whom she loves almost more than us.

As for me, I don’t know yet either that in ten years’ time, I will recognise, in a heap of pairs of spectacles almost five metres high at the Auschwitz Memorial, the frames that my father slipped into the top pocket of his jacket, the last time I saw him at the Café des Tourneurs. My little brother Claude doesn’t know that soon I will come looking for him, and that if he hadn’t said yes, if we hadn’t faced those years together, neither of us would have survived. My seven friends, Jacques, Boris, Rosine, Ernest, François, Marius, Enzo, don’t know that they are going to die shouting ‘Vive la France’, and almost all of them with a foreign accent.

I strongly suspect that my thoughts are confused, that the words will tumble over each other in my head, but from that Monday noon onwards and for the next two years, my heart is going to thump ceaselessly in my chest to the rhythm imposed by fear; I was afraid for two years, and sometimes I still wake up in the night with that same bloody feeling. But you are sleeping beside me, my love, even if I don’t know it yet. Anyway, here is a little of the story of Charles, Claude, Alonso, Catherine, Sophie, Rosine, Marc, Emile, Robert, my Spanish, Italian, Polish, Hungarian and Romanian friends, the children of freedom.

1

You must understand the context within which we were living; context is important, as in the case of a sentence, for example. Once removed from its context it often changes its meaning, and during the years to come, so many sentences will be removed from their context in order to judge in a partial way and to condemn more easily. It’s a habit that won’t be lost.

In the first days of September, Hitler’s armies had invaded Poland; France had declared war and nobody here or there doubted that our troops would drive back the enemy at the borders. Then the flood of German armoured divisions had swept through Belgium, and in a few weeks a hundred thousand of our soldiers would die on the battlefields of the North and the Somme.

Marshal Pétain was appointed to head the government; two days later, a general who refused to accept defeat launched an appeal for resistance from London. Pétain chose to sign the surrender of all our hopes. We had lost the war so quickly.

By swearing allegiance to Nazi Germany, Marshal Pétain led France into one of the darkest periods of her history. The Republic was abolished in favour of what would henceforth be called the French State. The map was divided by a horizontal line and the nation separated into two zones, one in the north, which was occupied, and the other in the south, which was allegedly free. But freedom there was entirely relative. Each day saw its share of decrees published, driving back into danger two million foreign men, women and children who now lived in France without rights: the right to carry out their professions, to go to school, to move around freely and soon, very soon, the very right to exist.

The nation had become amnesiac about the foreigners who came from Poland, Romania, Hungary, these Spanish or Italian refugees, and yet it had desperate need of them. It had been vitally necessary to repopulate a France that, twenty-five years earlier, had been deprived of a million and a half men who had died in the trenches of the Great War. Almost all my friends were foreigners, and they had all experienced the repression and abuses of power already perpetrated in their country for several years. German democrats knew who Hitler was, combatants in the Spanish Civil War knew about Franco’s dictatorship, and those from Italy knew about Mussolini’s Fascism. They had been the first witnesses of all the hatred, all the intolerance, of this pandemic that was infesting Europe, with its terrible funeral cortège of deaths and misery. Everyone already knew that defeat was only a foretaste; the worst was yet to come. But who would have wanted to listen to the bearers of bad news? France now no longer needed them. So, whether they had come from the East or the South, these exiles were arrested and interned in camps.

Marshal Pétain had not only given up, he was going to collude with Europe’s dictators, and in our country, which was falling asleep around this old man, they were all already crowding around: the head of the government, ministers, prefects, judges, the police, and the Militia; each more eager than the last to carry out their terrible work.

2

Everything began like a children’s game, three years earlier, on 10 November 1940. The unimpressive French Marshal, surrounded by a few prefects with silver laurels, came to Toulouse to start a tour of the free zone of a country that was in fact a prisoner of his defeat.

Those directionless crowds were a strange paradox, filled with wonder as they watched the Marshal raise his baton, the sceptre of a former leader who had returned to power, bringing a new order with him. But Pétain’s new order would be an order of misery, segregation, denunciations, exclusions, murders and barbarity.

Some of those who would soon form our brigade knew about the internment camps, where the French government had locked up all those who had made the mistake of being foreigners, Jews or Communists. And in these camps in the South West, whether at Gurs, Argelès, Noé or Rivesaltes, life was abominable. Suffice to say that for anyone who had friends or family members who were prisoners, the arrival of the Marshal felt like a final assault on the small amount of freedom we had left.

Since the population was preparing to acclaim this very Marshal, we had to sound our alarm bell, awake people from this terribly dangerous fear, this fear that overcomes crowds and leads them to throw in the towel, to accept anything; to keep silent, with the sole, cowardly excuse that their neighbours are doing the same and that if their neighbours are doing the same, then that’s what they should do.

For Caussat, one of my little brother’s best friends, for Bertrand, Clouet or Delacourt, there’s no question of throwing in the towel, no question of keeping silent, and the sinister parade that is about to take place in the streets of Toulouse will be the setting for a committed declaration.

What matters today is that words of truth, a few words of courage and dignity, rain down upon the procession. A text that is clumsily written, but that nonetheless denounces what ought to be denounced; and after that, what does it matter what the text says or doesn’t say? Then we still have to work out how to make the tracts as broadly balanced as possible, without getting ourselves arrested on the spot by the forces of order.

But my friends have it all worked out. A few hours before the procession, they cross Esquirol Square with armfuls of parcels. The police are on duty, but who cares about these innocent-looking adolescents? Here they are at the right spot, a building at the corner of rue de Metz. So, all four slip into the stairwell and climb up to the roof, hoping that there won’t be any observer up there. The horizon is empty and the city stretched out at their feet.

Caussat assembles the mechanism that he and his friends have devised. At the edge of the roof, a small board lies on a small trestle, ready to tip up like a swing. On one side they lay the pile of tracts that they have typed out, on the other side a can full of water. There is a small hole in the bottom of the vessel. Look: the water is trickling out into the guttering while they are already running off towards the street.

The Marshal’s car is approaching; Caussat lifts his head and smiles. The limousine, a convertible, moves slowly up the street. On the roof, the can is almost empty and no longer weighs anything; so the plank tips up and the tracts flutter down. Today, 10 November 1940, will be the felonious Marshal’s first autumn. Look at the sky: the sheets of paper pirouette and, to the supreme delight of these street urchins with their improvised courage, a few of them land on Marshal Pétain’s peaked cap. People in the crowd bend down and pick up the leaflets. There is total confusion, the police are running about in all directions, and those who think they seek these kids cheering the procession like all the others don’t realise that it’s their own first victory that they’re celebrating.

They have dispersed and are now going their separate ways. As he goes home this evening, Caussat cannot have any idea that three days later he’ll be denounced and arrested, and will spend two years in the municipal jails of Nîmes. Delacourt doesn’t know that in a few months he will be killed by French police officers in a church in Agen, after being pursued and taking refuge there; Clouet is unaware that, next year, he will be executed by firing squad in Lyon; as for Bertrand, nobody will find the corner of a field beneath which he lies. On leaving prison, his lungs eaten away by tuberculosis, Caussat will rejoin the Maquis. Arrested once again, this time he will be deported. He was twenty-two years old when he died at Buchenwald.

You see, for our friends, everything began like a children’s game, a game played by children who will never have time to become adults.

Those are the people I must talk to you about: Marcel Langer, Jan Gerhard, Jacques Insel, Charles Michalak, José Linarez Diaz, Stefan Barsony, and all those who will join them during the ensuing months. They are the first children of freedom, the ones who founded the 35th brigade. Why? In order to resist! It’s their story that matters, not mine, and forgive me if sometimes my memory fails me, if I’m confused or get a name wrong.

What do names matter, my friend Urman said one day; there were few of us but we were all one. We lived in fear, in secrecy, we didn’t know what the next day would bring, and it is still difficult now to reopen the memory of just one of those days.

3

Believe me, I give you my word, the war was never like a film; none of my friends had the face of Robert Mitchum, and if Odette had had even the legs of Lauren Bacall, I would probably have tried to kiss her instead of hesitating like a bloody fool outside the cinema. Particularly since it was shortly before the afternoon when two Nazis killed her at the corner of rue des Acacias. Since that day, I’ve never liked acacias.

The hardest thing, and I know it’s difficult to believe, was finding the Resistance.

Since the disappearance of Caussat and his friends, my little brother and I had been brooding. At high school, between the anti-Semitic comments of the teacher of history and geography, and the sarcastic remarks of the sixth-form boys we fought with, life wasn’t much fun. I spent my evenings next to the wireless set, listening for news from London. On our return to school for the autumn term, we found small leaflets on our desks entitled ‘Combat’. I saw the boy slip out of the classroom; he was an Alsatian refugee called Bergholtz. I ran at top speed to join him in the schoolyard, to tell him that I wanted to do what he did, distribute tracts for the Resistance. He laughed at me when I said that, but nonetheless I became his second-in-command. And in the days that followed, when school was over, I waited for him on the pavement. As soon as he reached the corner of the street I started walking, and he speeded up to join me. Together, we slid Gaullist newspapers into letterboxes; sometimes we threw them from the platforms of tramcars before jumping off while they were in motion and running away.

One evening, Bergholtz didn’t appear when school ended; or the next day, either…

From then on, when school ended I and my little brother Claude would take the little train that ran along beside the Moissac road. In secret, we went to the ‘Manor’. This was a large house where around thirty children were living in hiding – children whose parents had been deported: Girl Guides and Scouts had gathered them together and were taking care of them. Claude and I went there to hoe the vegetable garden, and sometimes gave lessons in maths and French to the youngest children. I took advantage of each day I spent at the Manor, to beg Josette, the woman in charge, to give me a lead that would enable me to join the Resistance, and each time, she looked at me, raised her eyes to the heavens, and pretended not to know what I was talking about.

But one day, Josette took me to one side in her office.

‘I think I have something for you. Go and stand outside number 25, rue Bayard, at two o’clock in the afternoon. A passer-by will ask you the time. You will tell him that your watch isn’t working. If he says to you “You’re not Jeannot, are you?” It’s the right man.’

And that’s exactly how it happened…

I took my little brother and we met Jacques outside 25, rue Bayard, in Toulouse.

He entered the street wearing a grey overcoat and felt hat, with a pipe in the corner of his mouth. He threw his newspaper into the bin fixed to the lamp-post; I didn’t pick it up because that wasn’t the instruction. The instruction was to wait until he asked me the time. He stopped beside us, looked us up and down and when I answered that my watch wasn’t working, he said he was called Jacques and asked which of us two was Jeannot. I immediately took a step forward, since the name was definitely mine.

Jacques recruited the partisans himself. He trusted no one and he was right. I know it’s not very generous to say that, but you have to see it in context.

At that moment, I did not know that in a few days’ time, a partisan called Marcel Langer would be sentenced to death because of a French prosecutor who had demanded his head and obtained it. And nobody in France, whether in the free zone or not, doubted that after one of our people had brought down that prosecutor outside his home, one Sunday on his way to mass, no court of law would dare to demand the head of an arrested partisan again.

Also, I did not know that I would kill a bastard, a senior official in the Militia, a denunciator and murderer of so many young resistors. The militiaman in question never knew that his death had hung by a thread. That I was so afraid of firing that I could have wet myself over it, that I almost dropped my weapon and that if that filth hadn’t said, ‘Have mercy,’ this man who’d never had any for anyone, I wouldn’t have been angry enough to bring him down with five bullets in the belly.

We killed people. I’ve spent years saying it: you never forget the face of someone you’re about to shoot. But we never killed an innocent, not even an imbecile. I know it, and my children will know it too. That’s what matters.

At the moment, Jacques is looking at me, weighing me up, sniffing me almost like an animal, trusting his instinct, and then he plants himself in front of me: what he will say in two minutes will change the course of my life.

‘What exactly do you want?’

‘To reach London.’

‘Then I can’t do anything for you,’ says Jacques. ‘London is a long way away and I don’t have any contacts.’

I’m expecting him to turn his back on me and walk away but Jacques stays in front of me. His eyes are still on me; I try again.

‘Can you put me in contact with the Maquis? I would like to go and fight with them.’

‘That is also impossible,’ Jacques continues, re-lighting his pipe.

‘Why?’

‘Because you say you want to fight. You don’t fight in the Maquis; at best you collect packages, pass on messages, but resistance there is still passive. If you want to fight, it’s with us.’

‘Us?’

‘Are you ready to fight in the streets?’

‘What I want is to kill a Nazi before I die. I want a revolver.’

I had said that proudly. Jacques burst out laughing. I didn’t understand what was so funny about it; in fact I even thought it was rather dramatic! And that was precisely what had made Jacques laugh.

‘You’ve read too many books; we’re going to have to teach you how to use your head.’

His paternalistic question had annoyed me a little, but I wasn’t going to let him see my irritation. For months I’d been attempting to establish contact with the Resistance and now I was in the process of spoiling everything.

I search for the right words that don’t come, words that testify that I am someone on whom the partisans can rely. Jacques figures this out and smiles, and in his eyes I suddenly see something that might be a spark of affection.

‘We don’t fight to die, but for life, do you understand?’

It doesn’t sound like much, but that phrase hit me like a massive punch. Those were the first words of hope I had heard since the start of the war, since I had begun living without rights, without status, deprived of all identity in this country that yesterday was still mine. I’m missing my father, my family too. What has happened? Everything around me has melted away; my life has been stolen from me, simply because I’m a Jew and that’s enough for many people to want me dead.

My little brother is waiting behind me. He suspects that something important is afoot, so he gives a little cough as a reminder that he’s there too. Jacques lays his hand on my shoulder.

‘Come on, let’s move. One of the first things you must learn is never to stay still, that’s how you’re spotted. A lad waiting in the street, in times like this, always arouses suspicion.’

And here we are, walking along a pavement in a dark alleyway, with Claude following close on our heels.

‘I may have some work for you. This evening, you’ll go and sleep at 15, rue du Ruisseau, with old Mme Dublanc, she’ll be your landlady. You will tell her that you’re both students. She will certainly ask you what has happened to Jérôme. Answer that you’re taking his place, and he’s left to find his family in the North.’

I guessed that this was an open sesame that would give us access to a roof and, who could tell, perhaps even a heated room. So, taking my role very seriously, I asked who this Jérôme was, so that I’d be well-informed if old Mme Dublanc tried to find out more about her new tenants. Jacques immediately brought me back to a harsher reality.