Полная версия

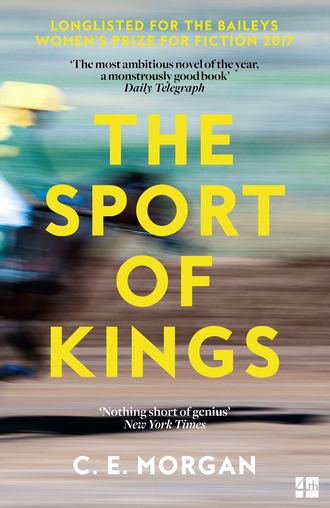

The Sport of Kings: Shortlisted for the Baileys Women’s Prize for Fiction 2017

“Get in here!” she said, her voice brooking no alternative.

Whether he was startled by her tone, or by the strange fact of youth wrangling age without reserve, he simply did as he was told and stood before her there in the pantry, looking down curiously with that diffident blankness she knew he’d earned by right of his skin, but which she had no sympathy for. Not today.

She raised a straight, slender finger right up to his face. “You idiot!” she hissed.

There was no change in his face, except his eyes narrowed almost imperceptibly, then he made a move to go, so she reached out and grasped up his shirtfront in her fist to pull him back around. Her grip was so hard it threatened the hold of the seams.

“Are you crazy?” she whispered, but to her own ears it sounded like hollering. “You know where you’re going to end up? Nigger, they’re going to hang you from a tree!”

He refused to answer, refused by turning again to leave, but Maryleen reached up with her free hand, and with a feeling of something near glee, which she would allow herself to acknowledge only later, she slapped him hard across the face.

He just stared at her in wordless shock while she said, “Have you lost your damn mind? Stop this madness! Don’t touch her again!”

And then, like an actor showing up late for his cue, the boy was in the kitchen, just standing there slack-armed between the butcher block and the sink, looking up into their faces with his mouth slightly ajar. Maryleen let loose Filip’s shirt, and the man was gone in an instant, shouldering past the boy, who stepped aside to let him go, all the while continuing to look up into Maryleen’s flushed face. He said, “I just wondered where everyone went.”

“We’ve been right here,” she said smartly, moving past him into the kitchen, so that she could reorder her expression without his eyes on her. “Right here the whole time.”

The boy turned slowly on his heels to watch her, but he didn’t follow. His face was soft, just the faint beginnings of an unreadable expression perched there.

“Where’s Mother?” he said slowly.

“How would I know?” Maryleen said gruffly with her back still turned.

“What were you and Filip arguing about?”

“Folks argue,” she said sharply. “It’s no concern of yours.”

“But—”

She turned quickly then, trying to project more passion and less fear than she felt. Her eyes were wide. “He said something nasty about my mother, all right? And I don’t care to talk about it anymore!”

Henry said nothing in response to this, only reared back slightly with distaste or wariness, and Maryleen made a quiet drama of calming herself for his benefit, but she could have cried with relief when he finally walked haltingly, sullenly to the kitchen door that led outside. He stood there on the step for a long moment with his hands in his pockets, surveying the orchard, which was quiet now, deserted, and full of ragged shadows. Then he walked out onto the grass lit yellow with the fading afternoon, and he turned suddenly. Maryleen, who’d been eyeing him like a hawk from the kitchen window, thrust her hands under the faucet and pretended to wash, but from the side of her eyes, she watched as Henry cast a wary glance back over the house, looking it up and down. And though she didn’t believe in God at all, and certainly not in some white man in the sky who’d sanctioned everything evil in this world, she prayed.

Church: the father, the son, the holy ghost, and his mother—his own original, originating Lavinia!—who always fanned Henry’s heavy head when he nodded off, enveloping him in a rosed perfume and the unnamed scent of her person. There was a change in her son, she eyed him now with the wariness of a doe that senses the hunter is afoot. He didn’t lean into her on the pew anymore, didn’t doze like a child against her shoulder; he no longer smiled.

Dark dissatisfaction ran through him like a coal seam. He no longer cared for the old, unsatisfying stories, the Bible just a crass country cousin to the myths and nothing more. He counted the commandments: Honor thy mother and thy father. Really? Why? So you could climb some rickety ladder to heaven? When he sat in those worn pews and tried to imagine God’s heaven, all he could conjure was a glistering expanse of nothingness. Roads of gold stretched without event farther than imagination, farther than forever, until his hope of heaven was a distress, and his heart flagged in his chest. Henry knew you had to make your own heaven—a place where, when your mother said she loved you above all others, it meant that she loved you more than a lover, more than God. He was newly sick to his stomach. Was church the wrong place to pray for the death of a man?

The ride back to Forge Run was an exercise in strained silence, his father concentrating on the road, Henry turned mulishly to the passing fields. The theater of razed greenery was fading before their eyes under the blue autumn sky, death hatching a mottled dun on the withering shocks. Their dying bored him to death. Easy come, easy go. His eyes slashed the back of his father’s head, and his tongue felt perverse. Loose. He could not latch it to his better sense, which was silence. He said, “I can’t stand to listen to all that preaching about rules.” His voice felt like breaking something.

There was no immediate response. His father seemed determined to teach him the rudest of life lessons: there is nothing worse than being ignored.

“I’m tired of rules for no reasons.” This time his belligerence was barely contained.

Without turning his head, John Henry said, “That you don’t understand the reason for a rule is no indication of its absence.”

Henry sulked, his shoulders crouching down around his spine. Then he reached forward suddenly and pressed on his mother’s shoulder until she turned.

“Do you believe God answers prayers?”

She raised her brows, her pretty mouth puckered, and they both inclined their heads in mutual misunderstanding like confused dancers curtsying.

“Yes or no?” he said, impatient.

“Leave your mother be,” said John Henry, but the boy was staring at his mother angrily and frowning.

Do you understand me? he signed.

She nodded.

Do you understand the preacher? he signed with terse, pithy gestures.

She smiled a smile like an apology.

“You mean you don’t understand him?” He said this out loud.

She shrugged.

“Father!” he cried accusingly. “She doesn’t even understand what the preacher’s saying! I always thought she was reading his lips!”

John Henry said nothing.

“Then why even bother going to church?” he spat, but his mother was swiveling away from him to face forward. He tapped her on her shoulder, hard, and he said, “Why even go, then?” And then she turned and brushed at his hand as if it were a fly and not her own son, and he had never seen her do that. He sat back in surprise.

“Be quiet, Henry,” said his father, one slate eye to the rearview mirror.

Henry seethed, clenched his jaw, and locked eyes with John Henry. His mother ignored them both and gazed out her window, refusing them. Henry fairly boiled with irritation all the way home, but when they reached the house, John Henry didn’t cut the purring motor as expected, or pull alongside the house. Instead, he idled on the circular drive that traced the front of the estate. He gestured to his wife to go on in without them, so she slid from her seat and stood awkwardly on the drive. Henry refused to look at her, only assumed her place slump-shouldered, and John Henry eased down the lane again. No one looked back to see Lavinia standing still where she had been, a solitary figure with a bright yellow clutch tight in her hands, her face cast in shadow by her half veil.

Henry wanted to ask where they were going, but he refused to speak, so they drove in silence, two men hard and unbending with thirty-five years between them. Henry wrapped his arms around himself, though it was warm enough in the car, closing his eyes and feigning disinterest. When he opened them, he didn’t know where they were and recognized none of the farms on either side of the road.

He finally buckled. “Where are we going?”

“I want to show you something,” said John Henry, “because of your recent concerns.”

“About what?” In the ensuing silence, his regret was instant. His father was always biding his time, withholding answers like scraps from a bitch.

When they turned east onto a new gravel road, John Henry slacked his speed and coasted to the top of a gradual incline, where they attained a broad view of the green, rolling hills. They parked on the side of the road and John Henry pointed, but it was not necessary, because there was nothing else to see but the farm.

The property was situated directly before them, a vast spread of impossibly verdant green that rolled like ocean swells, the bright fields curbed by virgin white plank fencing. The scattered barns and outbuildings were dressed in white and green, all cupolaed and topped by striding iron horses not yet gone to verdigris in the weather. The vanes wheeled and spun in a high wind that seemed to come from all directions at once. The barns were pristine, no dirt or manure to mar their snowy sides, no stray chaff or markings on the sun-sparked fan windows. Brick walks paved paths from building to building, and men led horses into paddocks and out of barns, and the horses were dark and leggy. North of the barns, far beyond the horses, the main house was an astonishment: Ionic-columned and endlessly gabled, shingled in a gray almost white, and built to four towering stories, from which it gazed down on the adventure of its own beauty. The acreage stretched beyond sight in all directions but one, and there a threadbare tobacco barn stood beyond the last line of fencing, a poor and classless interloper, only its upper half visible from its perch on a declivitous slope, where it leaned away from its new neighbors, boards rafting into disrepair, a sorry sight before stupendous wealth.

John Henry sat quietly, his heavy hands on the wheel. “Tell me what you see,” he said.

Henry tore his eyes from the groomed land and looked at his father, weighing the truth against the trap he sensed there. “A horse farm,” he said cautiously, reluctantly, the words drawn out of him by sheer paternal force.

John Henry’s lips pinched into a hard smile. “Spoken like a child with a child’s understanding. Henry, I intend to have this conversation with you only once, and then the subject will be closed. Let me tell you what a grown man, a man of discernment, sees. What looks like a horse farm is really a cheap attempt at dignity. All these pretty things before you amount to a heap of goddamn rhinestones. Caveat emptor: significance is not for sale. Dignity can’t be purchased, Henry, least of all by these latecomers, these … these outsiders, who dress up their addictions in Sunday clothes and Derby hats. People call it a sport, but I’ll tell you this: this so-called sport is driven by compulsion, and weak men love nothing more than to abandon themselves to their compulsions.”

He turned to his son now, something raw in his eyes, though his voice remained low and controlled. “I saw that in the war,” he said. “And I believe you’ve seen it in our neighbor, Mr. Osbourne, who’s an embarrassment as far as I’m concerned. The man knows nothing about animal husbandry, nothing about the proper raising of horses, and his Wild West simpletons know even less. A gunshot wound, however impressively heroic it may appear to you, is merely the kind of excuse a weak man seizes upon to wriggle his way out of his real responsibilities. The very definition of a white goddamned nigger.”

He considered for a moment. “Henry, the education I’m purchasing for you is to keep you on the established path. Do you understand me? This …” He spread a hand forward toward the fields like an indignant blossom, his palm a ruddy ocelle, his fingers hard petals. “This is nothing but a rich man’s game, where he bets his better self and loses.”

“But we’re rich,” said Henry.

“There are two different kinds of rich, Henry. Our family name depends on your ability to distinguish between the two.”

Henry did not respond immediately, but stared ahead at the sweep of this farm, its perfectly painted buildings shining like white knights standing guard over an emerald expanse. His one ear was trained to his father, but the other extended itself in the direction of the fields and whatever sounds might be rising from them, which were none. Nature was manicured into silence. The horses moved slowly in that distant silence as if underwater.

Again, his father pointed out over the wheel. “Look how they’re trying to outshine every modest tradition that the first families established here two hundred years ago. This is just ostentation. Does your mother need to dress like a common prostitute to prove her value?”

Henry looked down, startled.

“And look at this one here.”

Henry turned to watch the slow progress of a black man stooped over his mower as he traced the outer edge of the fencing. His face was turned down against the midmost glare of the sun. He moved as if burdened by an unearthly fatigue.

“Watch how he slouches around without any dignity whatsoever. Born colored but made a nigger by being caught up in all this—and he knows it. He’s panning for fool’s gold, and it demoralizes him. The black race has always depended upon our guidance to steward them into lives worth leading. A colored man uses his place of employment as a school to learn the best of what white society can offer. It’s the only place he can hope to better himself, regardless of what the restless voices may shout from time to time. The irony of Negro intelligence is that it makes them aware of the poverty of their own intellect. The only proper response to white influence is humility. And the only right schooling is correction. To whatever degree is necessary.”

“But it doesn’t have to be as fancy as all this,” said Henry. “Mr. Osbourne just—”

“To condescend to any of this would be to insult your family.”

Henry’s eyes escaped his father’s and returned to the man at his mower. The boy’s heart rebelled, but there was a kind of plain disregard in the man’s body; he saw that, and it disappointed him.

“There’s a long line behind you, Henry.”

“I know,” he whispered, his mouth and eyes appearing downcast, but they were only distracted by his warring selves.

“Look at me, Henry, when I’m speaking to you.”

He looked at his father.

“You need to think like a man, not a child. There’s a sore temptation upon youth to discard with tradition, but tradition is learning collected. You’re a fool if you forget that and are forced to relearn what so many men before you have already learned. You owe obedience to them and you owe obedience to me, just as I owe it to them, and I owe it to my father, in greater degree than my brother because I am the eldest. All roads have led to you, Henry, and I won’t have you throw everything away for a heap of rhinestones. I’m a planter’s son, and you’re a planter’s son. There is no need for improvement, Henry, only adherence to a line that has never altered, because it’s never proven unsound. Have I made myself clear?”

“Yes, sir,” Henry said thinly.

His father narrowed his eyes. “Say it.”

“Say what?”

“Say right now whatever it is you want to say. This is the one and only time we’re going to have this conversation.”

“Well … I …,” Henry skated. “Don’t flirt with your words.”

“What if,” Henry rushed, “what if your father had asked you to marry a different woman?”

John Henry reared his head back slightly, but he didn’t hesitate. He saw clear through his boy. “I would have married her,” he said, “just as he wanted me to.”

“But—”

“I would have married her,” he repeated firmly. “But I was smart enough to choose a woman of whom I knew he would approve. She came from good stock, she was beautiful and—”

“Never talked too much,” said Henry.

John Henry paused, his shrewd eyes gathering up the meaning in Henry’s face, but then he smiled slowly as if they were sharing the joke. His shoulders eased in his suit jacket. He brought his hands together now, so his fingertips touched. “I told your mother I’d be taking you to dinner this afternoon to a restaurant where I take my clients. They don’t normally admit children, but I spoke with them earlier and made an arrangement. Would that be to your liking?”

Henry nodded straight-faced and without speaking, his head bobbing in a mime of obligation. But then he pressed himself back into his seat and tasted the word “children” in his mouth as if it were something too vile to swallow. John Henry restarted the sedan, and Henry didn’t turn his head to the left or the right but watched the farm pass from the corner of his eye, so it washed by like a grassy stream through which horses ran.

In the house, Lavinia waited, unable to step away from the window until she saw the sedan pull up the long drive in the interminable stretch between sundown and darkness. Her nails were bitten to the quick. She assumed her old, reliable smile and stretched out her arms when her son walked through the kitchen door. But when she stepped to him, he pushed her arm away from him with startling force and charged up the back staircase, so she felt the vibrations on the steps like hammer blows. Whatever it was that he said in that moment with his back to her, she didn’t hear.

In the wintertime, John Henry took his bourbon in the front parlor. He returned home from Paris by five thirty and dinner emerged from Maryleen’s kitchen no later than six o’clock. Then, satisfied and regardless of desperate cold or wild easterly wind, he would stand for some time on the el porch, watch the snowy farm weather to gray as the stars spangled out of the black, feeling the night freezing and contracting around him. By the time Venus was setting in the south, he had returned to the parlor, where he could enjoy his solitude for another hour or so before bedtime. He unlaced and removed his black wing tips, placing them side by side on the Aubusson, and selected a seventy-eight for the player. Then he smoked a single Dominican cigar, which he removed from a carved bone box on the mantel, and sat on the davenport to read the Lexington Leader. He did this every winter evening without fail.

Henry knew the rule: no one disturbed his father. But this evening he fretted pensively along the front hall, end to end, his weight distressing the old heartwood planks until the record screeched suddenly and his father called out, “Stop that incessant pacing right now!”

Henry peered swiftly around the doorway to the parlor. His father stood there in his black socks in front of the davenport, the newspaper wrenched up in one hand.

“I knew it wasn’t your mother. She never makes a sound,” he said. To Henry’s surprise, there was a hint of smile in his father’s eyes.

“May I speak with you, Father?” Careful, discreet, he glanced both ways down the hall.

The smile vanished. “Henry, we will not be discussing horses again.”

“No, sir, I know. It’s not about that.”

“Come in, then. I was meaning to speak with you anyway. I wanted to tell you that I found a tutor for you. He may not look like much, but his credentials are impeccable.”

Henry stepped into the room and closed the door as his father regarded him. In his stocking feet, the man was six feet but had grown somewhat thicker through the waist and redder, like the sun was turning him, his freckles now mixed with age spots. The cupreous, stalwart bulk of him was lessened somehow, and his son arrived at the fact of it without sentimentality, with eagerness even.

John Henry said, “I’ll give you five minutes, and then I would prefer to return to my reading.” He seated himself again on the davenport with the paper, his eyes peering directly over it at his son. Waiting.

“Father,” began Henry, and though his body urged him to sit in the wing chair opposite his father, he forced himself to sit cross-legged at his feet like a servant, beside his emptied and stinking shoes. Quietly, he said, “Father, why is everyone so upset?”

“Upset?” His father’s large head reared back, consternation on his brow.

“I mean, in the news. There’s so much happening. It seems like there’s more unrest every day.”

“Ah. Yes, that’s right,” John Henry said, nodding. “It’s a distressing time in many ways, an embarrassing time. It will only get worse, I imagine. No one—absolutely no one—remembers their place anymore, and we will all pay the price for this kind of national amnesia.”

Careful, steady, his face full of concern. “Is it true that they plan to desegregate the schools? What will happen after that?”

“After that?” his father said, and laughed. “After that, there will be social chaos and a breakdown in the educational system, and the Negro will be the first in line asking us to come back and fix it all. He never hesitates to implore others to come in and clean up the mess that results from his demands. His children, of course, will end up suffering the most. That’s what always happens. He is simply incapable of predicting the consequences of his actions. There is potential in some of them, but as your grandfather used to say, the Negro is our Socratic shadow. I think the allusion is apt.”

John Henry lowered his paper and folded it. “You see, in the end, Henry, de jure segregation may be stripped in some segments of the society—in fact, it appears almost inevitable now—but de facto divisions will always remain. Segregation is inherent, natural, and inevitable, no matter what the dreamers would like to think, no matter what the town of Berea would have us believe. Bring twenty white men and twenty colored into a new town and within a week, the white men will be successful landowners and the colored will be tenants. Good tenants, perhaps, but tenants nonetheless. Nothing wrong with that. The world always needs good tenants.”

“I heard they’ll send in the military to force the schools open if they have to.”

John Henry shook his head. “If it actually comes to that, there will be decent, God-fearing citizens to block the way. Men like Byrd. There’s certainly nothing to be afraid of.”

Henry sat up straight, indignant. “Oh, I’m not afraid. Did you hear what Senator Darby—”

“Darby!” snorted John Henry. “Darby’s a fool. He makes the Southerner appear the blubbering idiot, which is precisely what Northerners want in order to vilify the South—a vision of the South as mindless cracker. It makes them feel virtuous, when in fact they know absolutely nothing of the Southern situation. Darby!” He snorted again.

“The North—”

“The North is far more segregated than we could be, given the fact that half of our population is colored and we interact with one another constantly—daily. The Negro lives in our very homes and always has. The North can’t even fathom. The North doesn’t even know what a Negro is.

“You see, Henry, for them the race problem is either a mental abstraction or a romance. For us, as perhaps you’re beginning to understand, it is a problem of practice and the everyday frustration of dealing with the colored appetite and intellect, which is entirely different from our own. It is quite easy to imagine the equality of all men when you sit on a high horse and don’t have to walk among them in the fields. Indeed, everyone appears the same height from that view. But demount the horse and it soon becomes apparent that there are not merely masters and slaves by happenstance, or overseers and laborers by happenstance, but that these divisions are inherent and unavoidable. God save the mark—there were slaves in the Republic, and these liberals would imagine themselves greater minds!”

Now his voice was rising, the color bloomed in his cheeks. “The problem, Henry, as I have always seen it, is that the Negro is fundamentally a child, and children are incapable of understanding their own inferiority. Indeed, they generally err on the side of grandiose delusion. Mind you, the Negro is naturally playful, with a great capacity for joy, and I can appreciate that. But he’s as self-pitying as he is playful, and like a child, he can despise you with as much passion in the evening as he loved and admired you with in the morning. Look at Filip—”