Полная версия

The Men Who United the States: The Amazing Stories of the Explorers, Inventors and Mavericks Who Made America

There were also continuing disputes raging within the science—between the plutonists and the neptunists, for example, or between the catastrophists and the calmer-minded supporters of uniformitarianism. And the aristocrats who had claimed the science for themselves—rich men who amassed gaudy collections of minerals and fossils to decorate the drawing rooms of their mansions—were also at the time beginning to yield to a wider public sense of inquiry, with every farmer and walker and settler keeping an eye on the land, curious to know what it was made of and why.

But for some, the academic din in Europe proved perhaps just a little too much. William Maclure soon came back to America, admitting to being overwhelmed by the topographic complexity of the European landscape. He decided he would instead be more suitably self-employed discovering the geology of his newly adopted homeland. He would find out what America was made of, he decided. And he would draw a map of it.

DRAWING THE COLORS OF ROCKS

This was in 1799. For the next ten years, Maclure tramped and stagecoached relentlessly up and down and across the narrow swath of territory that lay between the Appalachians and the Atlantic—the country’s most known and settled region. He wandered on the far side of the Alleghenies, too, through what is now Arkansas and Mississippi, though it is not certain if he managed to get as far north as the sparsely settled territories of Ohio and Indiana. He managed to get himself all the way down to Georgia. We cannot be certain that he got all the way up to Maine, but he did claim to have crossed the hills and valleys of the Appalachians at least twenty-two times—which, given the condition of the roads at the time, was no mean achievement.

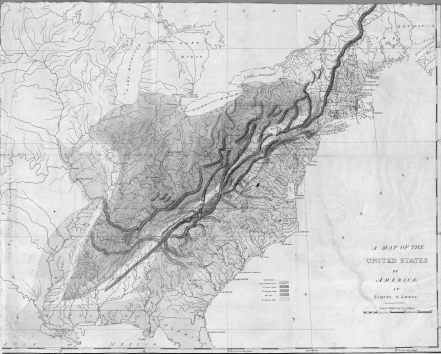

But however he did it, wherever he happened to go, however many miles he walked, rode, or went in greater comfort by carriage and diligence and cart, he achieved something truly memorable, with a significance that went beyond what might have seemed its purely American relevance. He announced it in an address before an evening meeting of the American Philosophical Society in 1809 after offering his first thoughts on the geology of the nation. Crucially, he included with his seventeen pages of explanation a hand-colored map—the first geological map in the world, some say, and certainly the first recognizable geological map of the United States.

It is a document of curious beauty, even though its simple innocence rendered it of little real use. It is based on a topographic map engraved by Samuel Lewis, a Philadelphia mapmaker who was at the time perhaps the country’s preeminent cartographer.1 Maclure used vivid watercolors—yellow, red, blue, pink, and green—to paint onto the base map’s eastern half the five main divisions, as early geology was inclined to see them, of America’s rocks.

The swaths of color he used—to show different kinds of rock, not different ages, as maps do today—all trend across the states from the southwest up to the northeast. They sweep along in approximate parallel to the lines of the Appalachian hills—which on the map sheet are picked out in caterpillarlike lines of ugly fuzziness; that was the device Lewis had employed to depict chains of mountains on all of his maps.

The results of Maclure’s estimated fifty survey journeys across the Appalachians led to the publication in 1809 of this crude but memorable first geological map of the then United States. It predated by six years the much more famous British map by William Smith.

Four basic types of rock make up the geology of America, as it was described in 1809. On the western side of the mountains, everything on Maclure’s map is colored pale blue, indicating the presence of so-called secondary rocks, fossil-bearing sediments, by and large. On the eastern side, the ocean side, all is by contrast hand-colored yellow, indicating alluvial rocks, gravels and sands and fresh-from-the-ocean clays.

The summits of the Appalachian mountain ranges Maclure showed to be quite geologically different and painted them in vivid streaks of deep blue and deep red denoting what early geological theorists called transition rocks. He also noted the presence of hard granitic outcrops of what he called primitive rocks; these he colored in pink. And for good measure, he also invented a fifth category for deposits of rock salt.

As art, Maclure’s maps—he made a revised version in 1818—are undeniably pretty; but as science, they were confusing and, in truth, pretty useless. Had they been Maclure’s sole achievement, he might then have slipped into obscurity. But that was not to be.

THE WELLSPRING OF KNOWLEDGE

Maclure’s eagerness to instill in American working-class youth a love for the practical—for the skills of farming; for a knowledge of geography; for the learning of natural history, statistics, biology—remained for years little more than an unrealized dream. But all changed in 1824, when he traveled to Scotland and had his first meeting with Robert Owen. That was when he was first seized with the idea of joining a utopian commune, transforming himself from a mapmaker into a missionary, and becoming America’s first geological messiah.

Owen was a Welshman who had made his fortune from the spinning of cotton in Scotland. He had carefully created in New Lanark a showpiece of social engineering for his mill workers—a near-ideal industrial environment, as he saw it, a community that was clean, healthy, well paid, disciplined, and morally sound, its children better educated than those in the finest paid schools in the land. So successful and admired had been New Lanark that Owen decided to expand. In the winter of 1824, he took his millennial dreams and blueprints for popular communal perfection across to America and started the process without delay by buying all of the land and real estate that the departing German settlers had created for themselves in New Harmony.

He reasoned that two thousand or so people could live together around an immense quadrangle he would build in the town. They would govern themselves, farm the land collectively and intelligently, live congenially without money, commune among themselves in the gardens within the buildings, and discipline themselves to hard work and moderate celibacy. His ideals were to all intents and purposes the ideals of the early Soviets, with communities to be run according to the familiar Marxist precept of fifty years later: “From each according to his ability, to each according to his needs.”

After settling his purchase of New Harmony, he came back east on a whirlwind recruiting mission. The fame he had won from his Scottish experiment preceded him, and as a successful industrialist, he found immediate and ready acceptance everywhere. At least, he did at first. He was able to meet without difficulty all of the privileged and the progressive figures of the Philadelphia Main Line, as well as chiefs of two Indian tribes. He won an audience with President Monroe, took tea with Thomas Jefferson and James Madison, and gave two public lectures in the Capitol. John Quincy Adams, the president-elect, came to both talks, and was so taken that he had Owen build a scale model of his proposed New Harmony building and display it at the White House.

It was while he was in Pennsylvania that Owen achieved his greatest coup, the one whose effects would linger longest, in managing to persuade William Maclure to come on board.

At the time, Maclure, his mapmaking success well in his past, had won fresh fame as a campaigning education reformer; and as president of the American Academy of Natural Sciences, he was seen not just as one of the preeminent scientists of his time, but as a great educational theorist, too. At their first meeting, Owen lost no time in reminding Maclure of his own, rather similar credentials. He assured him that what Maclure had seen of his success back in Scotland just a matter of months earlier could and should now be re-created in America.

What followed was an epiphany. After an initial bout of dithering—he was shrewdly wary of Owen’s eccentricities and shortcomings, even then—William Maclure finally and decisively bought into the revolutionary plans. He agreed. He would uproot himself from the comforts of his Pennsylvania life, move the eight hundred miles across and down to New Harmony, and throw in his lot with Owen’s strange new settlement.

Moreover, and more important still, he persuaded a number of his scientific colleagues to come along with him. They were a die-hard group, young men and women, also largely from Pennsylvania, who thought the idea of going off to live in Owen’s eccentric new commune was both worthy and noble. Most of those who volunteered were younger than Maclure. All were as eager as he was to teach youngsters the knowledge they had accrued. All were dreamy and impractical idealists.

So he made the journey a suitably impractical adventure. Rather than have the party travel down to Indiana in the comfort of the stagecoach, Maclure had them all go down on a boat. It was a shallow-draft keelboat, with barely room for forty, rowed by six oarsmen. Officially it was named the Philanthropist, but Owen proclaimed that “it contained more learning than ever was before contained in a boat,” so it was and still is informally known as the Boatload of Knowledge.

The vessel took off down the Ohio River from Pittsburgh on a bitter Sunday in late November 1825. After punching its way though the ice for the next seven weeks—its passengers listening to the onboard piano, taking off for skating ventures, reciting poetry and reading, reading—everyone arrived at New Harmony on a bitter cold day in late January. Fifty tons of books and what was termed “philosophic apparatus” joined them a few days later, whereupon the team promptly began—under the supervision of Maclure and Owen (who had come down at ease, on the stagecoach)—a hyperactive program of teaching to all and any of the youngsters from the towns nearby, just what they had to offer.

But there was more hyperactivity than most had bargained for. The furious energy of Owen’s New Harmony experiment barely survived Maclure’s arrival. The enthusiasm sputtered out within weeks, and the community soon began to fail, and it did so miserably and quickly. As is so often the way with utopias, factions developed—no fewer than ten had formed within just two years of Owen’s arrival, and all began bickering, squabbling, and arguing for various rewritings of the commune rules, each splinter group jostling for ideological supremacy. In the end, a demoralized and disillusioned Owen, shocked at a brand of waywardness he had never experienced back home among the Scots, returned to Britain. His confidence was sorely shaken: his ideas for the universal betterment of the working classes began slowly to evaporate, and he became steadily ever more marginalized and ridiculed a figure.2

But William Maclure did not immediately leave New Harmony. He remained behind to use the community as a base to preach the benefits of science and science education—and most especially the value of geology, the science that had first anchored him to America.

And in that sole regard, New Harmony was to become in this fresh incarnation something of a success. Maclure saw to it that the leaders of the more quarrelsome factions were persuaded to leave, that houses were now bought and sold and rents were expected and paid, that new shops were opened, and that the vigor of commercial life replaced the rigor of communal life. A printing shop was set up, and produce from the gardens was sent down to be sold in New Orleans.

Most of all, Maclure began to plan and finance his revolutionary education system, preaching and then practicing in town his long-held beliefs in the gift of free education for the American working youth. He gave his superb personal library to the town and opened it for the benefit of all. The young scientists—botanists, physicians, geologists—who had come down with him on the Boatload of Knowledge were to be the first teachers in the schools that were opened, and soon students came from towns and villages both nearby and far away. The town began to flourish again, and soon began to win a reputation—which spread nationwide—as a center of educational excellence.

Members of the community began to write books: there would soon be definitive multivolume works on fish, insects, the shells of mollusks, and the trees of North America. There was a resident engraver and color printer in New Harmony, too—and finely wrought monographs soon began to appear for sale at nearby fairs and bookstalls.

But William Maclure was beginning to feel his age. The Indiana winters were settling their cold deep into his bones. He started to take off on southerly explorations, finding himself eventually in Mexico, declaring a liking for it and settling on a new ambition to create progressive schools there. By 1830, when he was sixty-seven, he decided finally to cut loose from the winter cold of Indiana and stay put in the soothing balms of Mexico. He would for a while continue to finance New Harmony, but now only from afar.

THE TAPESTRY OF UNDERNEATH

The presiding intellectual genius who then ran New Harmony in his place was Robert Owen’s youngest son, David Dale Owen. who would become one of America’s leading geologists and a key player in the surveying of the nation as it expanded all the way westward across to the Pacific. William Maclure certainly started it all and is revered as the father of American geology in consequence. David Dale Owen, apprenticed in New Harmony, set in train the practical tasks that proved necessary for finding out what America was made of. Maclure had the vision and led the way; Robert Owen’s son went the distance and did the work.

When David Dale Owen was born, in 1807, there had been almost no geological maps made of anywhere. That soon began to change very rapidly, in response partly to Maclure’s American map of 1809 but more to William Smith’s map of England and Wales published in London in 1815, which demonstrated decisively how a proper stratigraphic map should be made. Not for nothing is Smith’s cartographic achievement still regarded as “the map that changed the world.” His revolutionary idea of illustrating the rocks according to their relative ages allowed for extrapolation and prediction: armed with a Smith map one could forecast with some certainty where a plunging coal seam might lead or where iron or copper—or one day, oil—could be found deep below the surface. By the time David Dale Owen assumed control of New Harmony, such mapping was standard practice in Europe, and both the federal government and state governments soon saw a pressing need to bring America similarly into order.

The first regions to be properly and systematically examined were in the Eastern states. The capital of New York State, Albany, was mapped in 1820 by Amos Eaton, a blacksmith’s son who two years earlier had published a cross section of America from the Catskill Mountains through Massachusetts to Boston and the Atlantic Ocean—a thing of sinuous curves and colors, showing the rock layers rising and falling in great subterranean swoops of blue and yellow that perhaps owe more to art than to science.

The practical demands of commerce soon introduced more scientific rigor to the mapmakers’ efforts: in 1832, Massachusetts became the first state to be systematically surveyed for its invisible underneath. The driving force behind the design was nakedly mercantile, the state’s governor demanding that the survey show “valuable ores … quarries … coal and lime formations … for the advancement of domestic prosperity.” Such imperatives would soon produce a torrent of new surveys and maps, invaluable guides to an America that was by now quickly evolving into an overwhelmingly industrialized nation.

The country’s mills, smelters, and forges were demanding iron and coal and copper—while wealthy city dwellers were demanding other precious metals and stones to be brought out from underground, too. Agriculture was expanding westward with the settlers: fertilizers were needed, and beds of phosphate and marl needed to be identified by a cadre of elite scientists who were now all of a sudden being seen as ever more vital to the national interest. The maps they made—not entirely comprehensible to most, true—were becoming popular items, in vogue at least among those eager to be able to forecast where needed treasures might be found.

David Dale Owen was a key player during this ebullient period in America’s expansionist history. His first duties involved helping with the geological survey of the state of Tennessee, which was begun in 1833. He was appointed assistant to a Dutchman, Gerard Troost, whom Tennessee had appointed to be its first-ever state geologist and who, as a passenger on the Boatload of Knowledge, had been a keen member of the utopian community. The men knew each other: both were legatees of Maclure’s ever-spreading influence, both were graduates of the New Harmony schools.

But there were to be many more. The United States Congress was at the time making certain that all American public land that held proven or suspected reserves of minerals—lead, iron, and coal in particular—be sold in an organized manner, without either favoritism or fraud. Owen, his skills honed in Tennessee, was next appointed an official in the General Land Office, the body that made both the rules and the sale, and in 1840 the agency demanded that he survey eleven thousand square miles of the ore-rich corners of Iowa, Wisconsin, and Illinois.

He achieved this survey with remarkable dispatch. Within two years, he had finished and had turned in to his superiors a report that encompassed “161 printed octavo pages, 25 plates and maps, including a colored geological map and several colored sections.” He had had help—no fewer than 139 assistants, every last one of them drawn from the schools in New Harmony, all of the young men trained by him and Maclure. According to an official history, Owen’s organization of the survey “was a feat of generalship which has never been equaled in American geological history … one more illustration of the energy, persistence, and virility of the Scotch emigrants and their descendants in America.” It was a testament also to the enduring role of New Harmony in the making of early America.

By the time Owen died, in 1860, at least twenty-eight states had organized well-established geological surveys. Scores of maps were being published from all sides. Moreover, geologists who had arrived by sea on the West Coast had looked carefully at California and Oregon and had declared that it was likely that great mineral wealth existed there, and that discoveries of great value, such as the one made at Sutter’s Mill in 1848, were likely to be repeated.

All of the land between the coasts was also soon about to yield to squadrons of men who were equipped just as Owen and the Eastern, Midwestern, Californian, and Oregonian explorers had been. American scientists would in short order offer up thousands of detailed and very beautiful cartographic images of how the entire country had been constructed. So the knowing of the country was now well under way, and with this knowledge came the pressing urge to settle those places now being revealed map by map, survey by survey. To settle places deemed suitable for living, for farming, for mining, or for the birth and nurturing of an unbridled frontier optimism—a territory that was fast being fashioned and united into something that for millions of settlers could soon be called a homeland.

SETTING THE LURES

It is surely a universal truth that men and women who choose voluntarily to pack up everything, acquire a wagon, set off down a rutted track into the sunset, and then endure weeks and months of privation, misery, and real danger in order to create new homes for themselves countless miles elsewhere must have a powerful reason for doing so. Modern America’s very existence is based on the awe-inspiring reality that thousands upon thousands made this very choice. And at first blush it appears they had just as many thousands of reasons for setting forth toward the sunset.

Nearly all were going off to the West because they imagined a better and more congenial life there. Perhaps some were afflicted by a goading restlessness, but only a few went out on a whim. Some were drawn by reasons religious, others were compelled by a need to escape—to get away from political persecution, from the hand of the law, the clutch of a pestilence,3 the misery of a failed romance, or the stench of an unsavory past. A number in America’s Eastern and Southern states found the whole business of segregation and slavery unpalatable, and imagined that out west they might encounter a more tolerant and liberal atmosphere.

But for most, the West was simply the Promised Land. “Eastward I go only by force,” said Thoreau, “but westward I go free.” And the pioneers who were bold enough to head in that direction did so, generally speaking, imbued with a spirit of ambition and adventure and an unyieldingly optimistic sense of enterprise.

And yet—what was it, more specifically than all of their stated reasons, that truly provided the lure? What intelligence was it that had produced the necessary temptation—the impetus, the final trigger, that decided a hitherto settled Easterner to obtain a wagon, to pack up all his belongings, to say farewell to scores, and then to head off for thousands of miles into the Western unknown?

The answer almost always had something to do with the land. People went in multitudes because of what they knew, what they had heard told, or what they suspected about the very earth of which the West was made.

They learned that the far reaches of the country held places that sported a variety of temptations. There might be vast acreage of thick black soils. There might be cliffs rich with exotic ores. Some might have found rivers running over gold-specked gravel beds. Wanderers might have returned with news of coal seams, tar pits, strangely glinting mineral crystals, deposits of marble, beds of rich red sandstones, or prairie tablelands and valleys covered with a wealth of grasses and flowers that, once tamed and watered, could be farmed and persuaded to yield measureless wealth. These were lands well suited to those who had the necessary ambition, vision, and endurance, for those possessed of the true grit.

It was from the 1820s onward that those in the East were first being told about the remarkable qualities of the Western lands, and were being told of them in great and fascinating detail. The information was contained in the often breathlessly excited reports of the men who had made the journey already. Some of these were American Fur Company trappers; some others were missionaries—two missionary women, Narcissa Whitman and Eliza Spalding, crossed the Continental Divide in 1836, and the husband of one came back east to tell of their adventures and to plead with others to come follow her example. Most reports, however, were sent back from soldiers or scientists accompanying those soldiers, who had been sent out officially by the United States government, charged with exploring the full extent of the trackless continent. Such men—and there were so many, a roll call risks becoming a blur—would turn out to be the vanguard of all the great migrations that followed soon after.

They were men like Edwin James, in 1820, who conducted a geological survey of the Appalachians, the Ozarks, and the foothills of the Rockies on an expedition run by a Major Long, United States Army. Or like Henry Schoolcraft, who went with one Major Cass to the headwaters of the Mississippi, also in 1820, and there found substantial deposits of copper, lead, and gypsum. In 1823 a geologist named William Keating found copper in West Virginia. In 1824 the heroic explorer, trapper, and mapmaker Jedediah Smith rediscovered the low and easy South Pass4 through the Rockies, and Benjamin Bonneville, who took a wagon train through it eight years later, wrote of his discovering the famous salt flats in Utah in 1832. Two years later still, the first-ever official United States geologist, George Featherstonhaugh, drew a remarkably accurate cross section of the country from Texas to the Atlantic Ocean, noting the presence of interesting-looking mineral deposits along the way.