Полная версия

The Men Who United the States: The Amazing Stories of the Explorers, Inventors and Mavericks Who Made America

So a year after I bought the land, I did the dull and responsible thing: I sold it—this time for $80,000. My melancholy was somewhat assuaged by having made a tidy profit. Yet the decision saddened me. It rankled. Montana had long been central to my dream, and it was trying to have to accept that it was not to be.

It must have been twenty years later that I returned. I stayed with the realtor who had sold me the land and who had then sold it for me. She had prospered, mightily. She and her husband lived in a stupendous mansion, had property on the Pacific coast of Canada, and lived, by their own admission, tremendously well. The land boom I first noticed had been sustained, had become overwhelming. Huge houses were being built high up in the hills, expensive restaurants were everywhere, the local airstrip was busy with private planes, and the road through the valley—the very track Lewis and Clark had taken two centuries before—was jammed with shiny four-wheel-drive trucks. People were complaining about the difficulty of getting help, because for working people there was suddenly nowhere affordable to live locally, and in cafés I heard wealthy newcomers expressing amazement that their gardeners or pool boys had to drive sixty miles each way to get to work.

For four days the realtor and I explored the valley, fascinated, mouths agape at the way everything had changed, so dramatically and so very quickly. But the rich outsiders who had bought into the Bitterroot Valley were never there, someone remarked: they spent just a few days, then went off to some other equally opulent corner of the world—and, my friend remarked, by doing so they created a kind of absence, a kind of poverty. The sense of community that had made the valley towns so special had evaporated. The beauty and solitude of the place, the kind of world that Norman Maclean and Wallace Stegner had so loved, was fast vanishing. It had much more to do with money.

And with that, my friend drove me down to my land. She had been waiting to tell me about it. She hadn’t wanted to depress me further, she said. I wasn’t quite certain what she meant.

So we drove down the old road, bumped across the stream, and came to a small paved highway that hadn’t been there before. We breasted the ridge where there was a fence and a “Private, No Trespassing” sign. We parked the car. The air was heavy with the smell of pine needles and horse dust. Everything began to look and feel familiar, and then, as we rounded a bend in the track, there at last was my land—a long sloping parcel of yellowing grass and rock, and on it, a house of such appalling vulgarity as quite beggared belief. Eaves and arches, wings and columns and a mighty porte cochere, all done in white and ocher stucco, with a long black Escalade parked outside.

The house must have been unimaginably expensive. But what of the land, the eighty acres I had briefly cherished? My friend coughed discreetly and looked at her feet before replying. It had last been put on the market, she said quietly, for one and a quarter million dollars.

There is indeed something—for some—quite magical about Montana.

SHORELINE PASSAGE

From here it was downhill all the way for the explorers. Sacagawea was in her element here: this was Shoshone country, and she knew the language, remembered friends, and could and did persuade the local people to supply packhorses for the difficult trek downhill. As soon as the expedition members discovered among the forests and the crags the most navigable of the swarms of westbound streams—the frighteningly all-whitewater Lochsa, and then what they called the Kooskooskee, but which is now the Clearwater—they began their descent in earnest.

They built themselves another clutch of canoes by hollowing out ponderosa pine trunks with hot embers, then set off, screaming down mountain rivers that had a combined length of no more than 120 miles (in a straight line less than 80) until the hills flattened out and the rapids became ever more sluggish and steady waters.

When they had left the Bitterroot Mountain headwaters of the Lochsa River, they were at 7,000 feet. When they reached “the leavel pine Countrey” at the end of the Clearwater River, which coincides with the western edge of the Rockies, they were only 740 feet above sea level. The party had thus descended almost a hundred feet with every westward mile of travel, reaching with stark suddenness the bone-dry grasslands of what is now eastern Washington State. The Snake River joins and takes over the Clearwater here, with a river-bisected pair of towns once colorfully known as Ragtown and Jawbone Flats but now called the more respectful and anodyne Lewiston and Clarkston.

Down on these waterless and treeless flats, the men’s moods seemed changed. They were now more like stable-scenting horses, creatures who were beginning the run for home and could scarcely be persuaded otherwise. They began to chew up remarkable daily distances—the now placid nature of the river helping, of course—and the team plowed across the prairies like men possessed.

The sea now tugging them west was still some hundreds of miles distant, but there was growing evidence that it did indeed lie not too far away now, just below the western horizon. One of the local Indian parties showed the explorers a sailor’s jacket, another a red-and-blue blanket made of cloth—both from one of the maritime expeditions that had already explored and charted the West Coast. They then saw sea otters in the river one day; and then, crucially for history, they glimpsed far away the snowcapped summit of one of the volcanoes of the coastal ranges known as the Cascades.

This moment—it was Saturday, October 19, and by now they had joined the great flow of the Columbia River—is of great importance because in his diary William Clark gives this mountain peak a name:

I discovered a high mountain of emence hight cover with Snow, this must be one of the mountains laid down by Vancouver, as seen from the mouth of the Columbia River, from the Course which it bears which is West I take it to be Mt. St. Helens.

Not unsurprisingly, there is dispute. Some historical geographers insist that Clark could not possibly have seen this particular peak from his reported location—and that the mountain he saw was actually the then unnamed Mount Adams. The distinction is important. For if the mountain he saw was Saint Helens, then he was noting without fanfare something that was transcendentally intercontinental. For the Royal Navy explorer Captain George Vancouver had already seen this mountain, by chance on exactly this October day thirteen years before, in 1792. He had been the one to name it. He had done so in homage to his great friend Alleyne Fitzherbert, who had just been made British ambassador to Spain and had been created Lord St. Helens to add dignity to his posting.

Vancouver had seen the mountain from its western side. Now William Clark reported seeing its eastern side, and in doing so he was also seeing the first far-side-of-the-continent entity that had already been seen and named by another non-native discoverer. The circle of unveiling had thus now been closed. A great blow had been struck for the geographic and topographic unification of America, for the making of trans-America, and for uniting what would in due course become, even out here, the United States of America.

Mount Saint Helens is a volcano known these days for its devastating and lethal eruptions (the latest in May 1980). Perhaps now it could be more suitably memorialized as the capstone for this first-ever attempt to unite the American states. It could be seen, if a little fancifully, as the capstone of the idea itself, or more prosaically as the fastening that finally closed and secured the fabric of human knowledge and imperial adventure that now covered the whole breadth of America. If, that is, it was the mountain that William Clark professed to have spotted from his vantage point on the high Columbia.

But no memorial to the moment stands on the banks of the river. Nothing stands to say, Here was America first United. Instead there are two less agreeable monuments, if you will, to modern American life.

One, at a place named Umatilla, is a secret and highly secure army base that was built specifically to destroy the nation’s stocks of nerve gas. The troops deployed here started work in the 1990s, and so numerous were the warheads filled with sarin and VX and mustard gas that they are still hard at it twenty years later.

The other monument, if such it deserves to be called, is an enormous silvery-looking factory—just as secret and secure in its own way as the Umatilla Army Depot—owned by the giant agribusiness corporation Con Agra. It is called Lamb Weston, and though it looks more like a steam-belching power station, it does make food, all of it out of potatoes. Its owners wouldn’t allow me access but instead referred me to a press release, which said in part:

Potato products are the most profitable food item on foodservice menus today. And no other product is so universally loved, so broadly versatile and available in so many styles, cuts and flavor profiles.

Local employees said that their plant makes french fries, one of the most popular of the humble potato’s “styles, cuts and flavor profiles,” for McDonald’s.

From here matters for the Lewis and Clark expedition changed fast, climatically and topographically. The dry plains gave way with startling suddenness to forest—rain forest, in fact, with low clouds and dripping moss. The river picked up speed as it squeezed through the Cascade ranges. There were rapids and small waterfalls—nowadays all smoothed and calmed by a succession of great dams, the Bonneville most notable among them. And then, once past the rapids, it seemed that in the ever-increasing risings and fallings that the team noticed each day, it might well now be affected by tides, from the sea. Sea frets—thick wet fogs smelling of fish and seaweed—began to trouble the scouts in the party, canoeists who were now having to pick their course carefully as they passed along on an ever-widening, shoal-rich estuary.

On November 6 it seemed that they might have attained their goal. “Ocian in view! O! the joy!” Clark’s line is often quoted. But he was wrong. Though they had done “4,212 miles from the Mouth of the Missouri R,” they were still in the Columbia estuary. It seemed so unfair: ocean waves were breaking into the bay, setting their craft rocking with an intensity as if they had been offshore. But it would be two more weeks of foul weather and disappointment before, at last, Lewis was able to disembark at a spot in full and undeniable view of the true Pacific and carve into a tree, just as Alexander Mackenzie had daubed onto that stone off Bella Coola twelve years before, a simple inscription: “By Land from the U. States in 1804 & 1805.”

They built a camp on the left bank of the estuary and called it Fort Clatsop out of respect for the friendly local tribe. They spent the winter there, hoping in vain that a ship might come and take them back home by way of Panama, thus sparing them another long trek across the country. In the end, of course, they opted to walk home and reached Saint Louis in late September 1806. They had not found a water route across the country; they had not found the Northwest Passage; but they had forged some kind of relationship with almost twenty distinct Native American tribes, though to what ultimate benefit remained uncertain. They had unified the nation in a purely geographic sense; they had achieved in the very crudest sense what Thomas Jefferson had expected of them. And they had gained a formidable amount of information, thousands of pages of fascination and wonder for all America to pore over for decades to come.

And Fort Clatsop would go on to become Astoria, after John Jacob Astor, a butcher’s son and flute maker of Walldorf, near Heidelberg, established just to its north the headquarters of the great fur-trading empire that made his one of the wealthiest families in America. The names Astor and occasionally Walldorf are now memorialized almost everywhere—in New York at the Public Library, the Waldorf-Astoria Hotel, Astor Place, and Astoria in Queens; in a novel, Astoria, by Washington Irving; in four American towns called Astor and three others called Astoria; in Britain in both Houses of Parliament; at Cliveden and Mackinac Island; in Waldorf salad; and in scandals aplenty—the catalog of achievement and memorial and fortune is as endless as the family’s present fecundity and its former (since the family’s star is now slightly dimmed) celebrity. There is also, on a hill outside the Oregon terminus town, a marble column of great height built by the Astor family in the 1920s, with an inner staircase that allows visitors to clamber up and see unimpeded the view that Lewis and Clark would have seen in that early winter of 1805.

Beyond where Fort Clatsop stood and where the city of Astoria now straggles, there was only ocean—the wide, gray, slow-moving, and entirely open Pacific Ocean—to be seen ahead. There was no farther point of land to the west. With their arrival at the mouth of the river and their crossing of the bar, America had been crossed and the continent physically unified by the travels and the travails of a party of newly made American men. President Thomas Jefferson’s intention had perhaps not been fully realized—his men had not opened a water route across the country, for the Rocky Mountains had proved to be an impenetrable barrier—but they now had accomplished something of unimaginable courage and determination. They could now declare that they knew—and America knew as well—just where America was.

The basic shape and size and topography of the continent now being satisfactorily established, all that was needed next, at least in the short term, was to find out just what America was. How had America’s land been made, what was it made of, and how could it best be settled and turned to American use and enjoyment? Or because America would in time become a nation built by peoples from all over the rest of the world, how could the land be employed for the use and enjoyment of all the rest of the planet?

The explorers had come first, as they always should. The scientists, bent on answering the questions that the explorers had posed, would inevitably come next. And then, guided by what these explorers told of their findings, would come the settlers, who would plant their flags and shovels deep in this hitherto untouched soil, deep in the virgin American earth.

… we pass each other alternately until we emerge from the fissure, out on the summit of a rock. And what a world of grandeur is spread before us! Below is the canyon through which the Colorado runs. We can trace its course for miles, and at points catch glimpses of the river. From the northwest comes the Green in a narrow winding gorge. From the northeast comes the Grand, through a canyon that seems bottomless from where we stand. Away to the west are lines of cliffs and ledges of rock—not such ledges as the reader may have seen where the quarryman splits his rocks, but ledges from which the gods might quarry mountains.

—JOHN WESLEY POWELL, ON FIRST SEEING THE GRAND CANYON, JULY 1869

At Pacific Springs, one of the crossroads of the western trail, a pile of gold-bearing quartz marked the road to California; the other road had a sign bearing the words “To Oregon.” Those who could read took the trail to Oregon.

—DOROTHY JOHANSEN, “A WORKING HYPOTHESIS FOR THE STUDY OF MIGRATIONS,” 1967

THE LASTING BENEFIT OF HARMONY

The small southwestern Indiana town of New Harmony is not much to see these days—just a clutch of frame houses on the banks of the slow-drifting Wabash River. It is neat and tidy, quiet and peaceful. Nine hundred or so people live there, deep in the lush countryside where Kentucky, Illinois, and Indiana meet, down in the broad alluvial farmlands of the Ohio and the Mississippi Rivers that sidle past, not too far away.

A closer look at the town will hint at links with an interesting past. There is a museum designed by Richard Meier; a roofless church of curious design, which turns out to have been built by Philip Johnson; and a pair of spectacular gates designed by the cubist sculptor Jacques Lipchitz. All were created to memorialize that brief time in the early nineteenth century when New Harmony, as its name might now suggest, was founded to be the spiritual center of a great social experiment.

It was among the earliest of a scattering of similarly optimistic, hope-filled communities that sprang up in the early days of the United States, but New Harmony enjoyed a peculiar connection with that most elemental and unifying aspect of the stripling American nation: its geology.

To understand the geology of a country is to understand and then to realize all of its possibilities—its wealth, its strengths, the nature and kinds and value of its resources. Geology, after all, and without any intended pun, underlies everything. Human settlement on an unknown landscape perforce depends on a deep knowledge of what and where is potentially being settled—on whether the geology of this region suits it to farming, to mining, or to industry heavy or light; whether this range of hills is traversable, this cold prairie is cultivable, this wide river is fordable.

There can be no gainsaying the importance of the first crude discoveries made by the geological pioneers of early America: their findings, surveys, maps, and forecasts were the guides and lures that tempted and then scattered millions of people across the country. Eighteenth-century geology, infant science though it still may have been, offered the keys to unlock the country’s promise, bringing men out to inhabit the farther reaches of this country and create their nation.

And the town of New Harmony, Indiana, was where this realization of geology’s importance was born.

The town, first simply named Harmonie, was settled initially by early-nineteenth-century Germans, men and women fleeing to America much as the Pilgrim Fathers had fled two centuries before, to escape religious restrictions back home. Their piety and hard work paid off quickly, and they eventually moved on to larger quarters, selling their tiny settlement to another idealist adventurer, the campaigning Welsh socialist Robert Owen. He, flushed with the success of a millworkers’ commune that he had organized outside Edinburgh, planned to establish a utopian beachhead in America, based on socialist ideals. He renamed the former German village New Harmony; and once he had settled during the winter of 1825, he invited like-minded idealists to join him.

Such was the educational reputation of Owen’s earlier Scottish experiment that New Harmony became an immediate magnet for intellectuals, philosophers, teachers—and, in particular, scientists. Geologists, most notably, pitched in with a special enthusiasm, such that at the peak of New Harmony’s fortunes, no fewer than seven geologists of considerable later distinction could be counted among the inhabitants.

This tiny town briefly became “a scientific center of national significance,” as the University of Southern Indiana describes it today. New Harmony can fairly be regarded more specifically as the birthplace of American geology—not least because Robert Owen’s closest colleague and ideological soul mate, an equally eccentric visionary who came to join him on the banks of the Wabash River, is generally acknowledged today to be American geology’s founding father. He, too, was a foreigner, a middle-aged Scotsman of wealth and distinction whose fortune was in no way connected to the science of the earth—William Maclure.

THE SCIENCE THAT CHANGED AMERICA

Robert Owen and William Maclure were both strange and remarkable men. Owen was a social reformer of lasting repute—though his fame remains largely in his home country, to which he eventually returned. But when it comes to the story of geology as a unifying force in the making of the United States, the person of William Maclure is the one to be remembered preeminently—even though, ironically, he was not really a geologist at all.

Maclure, born in southern Scotland in 1763, was by his early thirties already a very rich man. He had amassed a fortune as a trader, helped by the annuity from his equally successful Ayrshire father, in whose mercantile footsteps he followed. He had come to the American colonies when he was a teenager, had set up his own import-export business when he was only nineteen, and soon afterward, profoundly influenced by the revolutionary events of 1776 and 1789 in America and France, moved to Philadelphia, throwing in his lot with a society that seemed to him to embrace his own beliefs in fairness and equality. He assumed American citizenship in 1796 and promptly established himself as a fully paid-up member of Pennsylvania’s fast-growing patrician society.

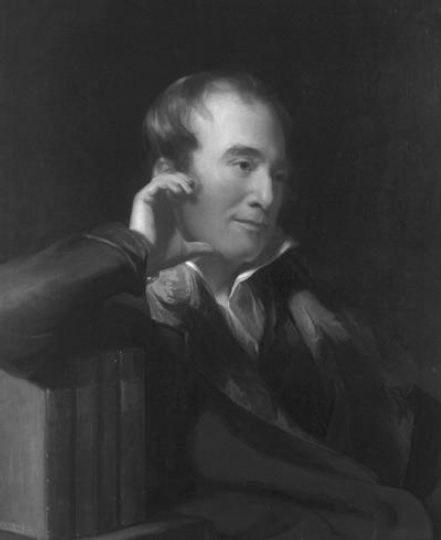

William Maclure, the wealthy Scotsman whose immense fortune allowed him time to indulge an early passion for American geology, and who in 1809 drew the country’s—and the world’s—first geological map.

Except that being merely patrician held little interest for a man of such a restless nature. No more than a year after becoming a citizen, when he might otherwise have started to enjoy the sedate comforts of early middle age, he made two important decisions.

He first decided to devote much of his remaining life to promoting educational reforms among America’s working classes. He vowed, as Robert Owen had already vowed, unbeknownst to Maclure, that the farmer, the miller, and the forge master would each have the same access to society’s potential as he and his wealthy peers had already been granted. It might take him years, but he would at least now begin to make plans.

At thirty-six, he believed himself young enough and fit enough to take on such a challenge. He had already achieved great eminence among the East Coast thoughtful: he was a leading light in the fiercely intellectual American Philosophical Society, founded by Benjamin Franklin, and would later go on to help found and run the American Academy of Natural Sciences, the oldest such institution in the country today. He believed deeply in the unifying powers of democratized science.

His second idea was more precise, as he explained in a letter to a friend. He “adopted rock-hunting as an amusement.” Geology, he declared, was far preferable to the conventional bourgeois pursuits of hunting and fishing, not least because it was “most applicable to useful practical purposes.” Moreover, “it has always appeared to me that the science of geology was one of the simplest and easiest to acquire: the number of names to be learned is small, and the present nomenclature, although rather generic than specific, is not difficult.”

He first toyed with the science during a brief stay in Europe, delving into the small mysteries of its nomenclature at the very time when the numerous schisms that plagued the calling were at their most dramatic. Perhaps no science has ever been caught up in such turmoil. On the one hand, geologists were busily unleashing themselves from centuries of dogmatic interference from the church. The less pious of their number were no longer content to believe unquestioningly in such literal Bible-based teachings as the creation of the earth on a precise October date in 4004 BC, for instance.