Полная версия

On Europe

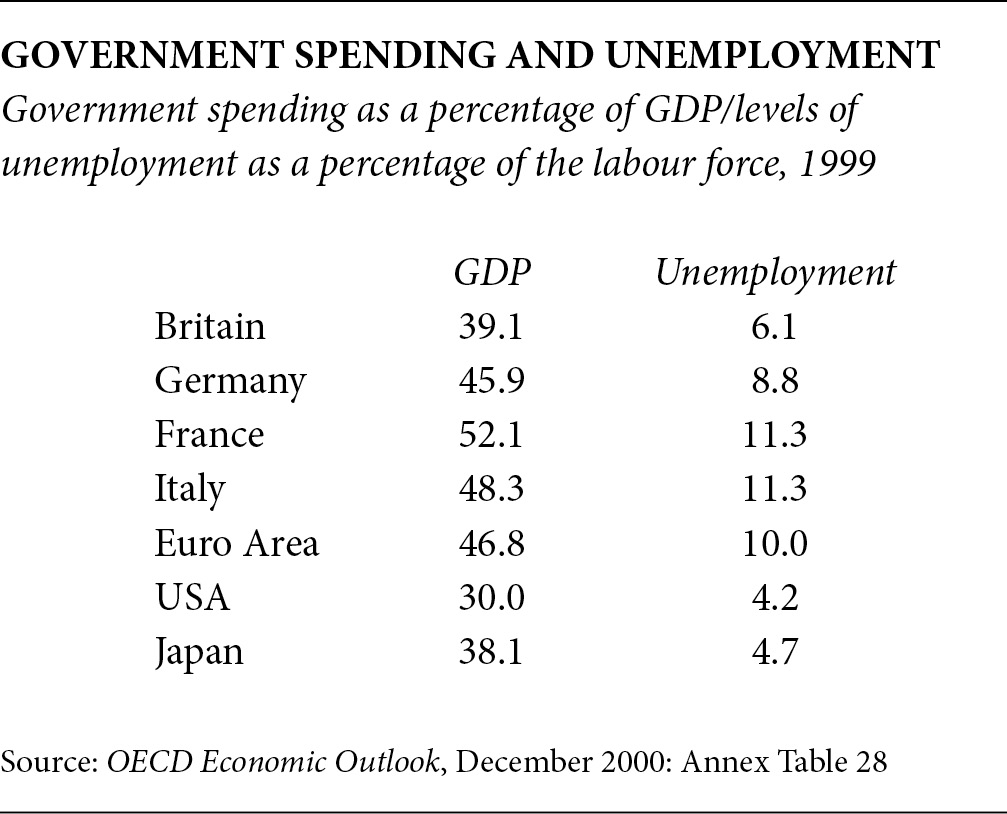

In fact, a number of authoritative studies have quite convincingly proved the opposite. Examining the impact of moves in France and Germany to stimulate employment by limiting working hours, Keith Marsden noted that at the same time as the average number of hours worked had fallen, the two countries’ unemployment rates had risen. By contrast, in the United States where people were working longer, and in Britain where working hours had remained stable, there had been significant falls in unemployment. Similarly, early-retirement programmes in Europe had not made available more opportunities for younger workers: rather, the effect had been to increase social security taxes to support the retired – so burdening business. Finally, Mr Marsden noted:

There is a clear correlation between higher government expenditure and lower employment. In the US, the government share of GDP was twenty-two percentage points below that of France but its employment ratio was fifteen points higher. Britain’s public spending level was eight points below Germany’s, yet its employment ratio was seven points higher.10

Another study of Europe’s social model by Bill Jamieson and Patrick Minford has highlighted the main economically harmful features of the European model: higher state spending, higher overall taxes, higher social security contributions – noting particularly the damaging burden this places on business – higher corporate taxes and higher levels of regulation, especially of labour markets. The results have been eminently predictable, but as an example of wilful self-damage no less shocking all the same: ‘The contrast with the United States is stark. Since 1970 the US economy has created almost fifty million new jobs, while the EU has created just five million.’11

EUROPE’S PENSIONS CRISIS

Another way of describing the difference between the European and the American models is to borrow a rather profound observation of Friedrich von Hayek. In The Road to Serfdom, first published in 1944, Hayek wrote:

[T]he policies which are now followed everywhere [in Europe], which hand out the privilege of security, now to this group and now to that, are nevertheless rapidly creating conditions in which the striving for security tends to become stronger than the love of freedom. The reason for this is that with every grant of complete security to one group the insecurity of the rest necessarily increases.12 [Emphasis added]

The European model epitomises precisely this: it places security above everything else, and in its persistence in eliminating risk it inevitably discourages enterprise. That is the basis of Europe’s pensions crisis, whose full implications are still not widely grasped.

Of course, in one sense the cause of the crisis is demography, the failure of much of Western society to reproduce. One can speculate about the causes for this and what it may tell us of contemporary values, attitudes and institutions. One can also debate whether and how policies might be changed to reverse long-term demographic decline. But such discussions, fascinating as they are, are irrelevant to the crisis much of Europe is facing now.

No less a person than the EU Commissioner in charge of the Internal Market and Taxation, Frits Bolkestein, has admitted that Europe faces a ‘pensions time-bomb’. He has noted that the ratio of workers to pensioners will decline from four to one to less than two to one by 2040. And he observes that if unfunded pension liabilities were shown up in the national accounts of some member states this would represent a debt of over 200 per cent of GDP.13 Italy is the EU country which is facing the worst crisis. It has a fertility rate of just 1.2, the lowest in the world, and also the world’s most costly pensions system, amounting to over 15 per cent of GDP – 33 per cent of worker payrolls, expected to rise to 50 per cent by 2030.14

Continental European countries have walked into a trap from which there appears no painless exit. Of course, they could not know just where demography would lead. But they have known well enough for some years that the promises implicitly made to pensioners could not be afforded. It was precisely because we realised the implications for Britain’s public finances that in 1980 we ended the connection between the retirement pension and incomes (it now rises in line with prices). And in 1986 we cut back state funding of the State Earnings-Related Pension Scheme (SERPS) and provided incentives to opt for private-sector Personal Pension Plans (PPPs). As a result, future state obligations have been curtailed to manageable levels. Britain also now has more money invested in pension funds than the rest of Europe put together. Although other EU countries have made repeated attempts to scale back their social liabilities, none has taken similar substantial steps. As a result, just three countries – the United States, Britain and Japan – possess three-quarters of the entire world’s funded pension assets.15

Quite how the countries of mainland Europe are going to cope with their problems is unclear. But someone is going to be disappointed – either pensioners or workers. And it seems that the official figures actually understate the scale of that disappointment. This is because it is not enough to express the problem in terms of national finances: it can only be understood in terms of equity between the generations. There is nothing theoretical about this. If one generation is expected to carry an excessive burden on behalf of another it will seek by every means to avoid it. It will either demand that past promises are broken, or it will not work, or it will not pay its taxes, or the most talented people will leave. Socialist governments which have tried to tax ‘till the pips squeak’ have ample experience of that. It is the main reason why even left-wing governments today try to keep marginal tax rates down. In the present case, and employing the concept of ‘generational accounts’ – which ‘represent the sum of all future net taxes (taxes paid minus transfer payments received) that citizens born in any given year will pay over their lifetimes, given current policy’ – Niall Ferguson and Laurence J. Kotlikoff have made various projections of the changes required to achieve ‘generational balance’. The scale of what is implied is illustrated by the conclusion that, for example, nine EU countries would need to cut government spending by more than 20 per cent if they wanted to rely on this means to achieve balance.16

THE COMMON AGRICULTURAL POLICY AND PROTECTION

Europe’s pensions problem is relatively recent. By contrast, its agriculture problem is of long standing. Although the European Common Market had its origins in a project to create a common policy towards coal and steel, it was the Common Agricultural Policy (CAP) which from the time of the Treaty of Rome was the central pillar of the structure.17 Political leaders and their policies come and go. Reform programmes rise and fall. But the CAP goes on for ever. No one seriously seeks to justify it. The days when we were told that without it Europe might be short of food have long since passed. Despite successive attempts at reform, not least those initiated by Britain, the CAP is wasteful, environmentally damaging and extremely costly. It still absorbs some £30 billion – about half of the EU’s total budget.18 But it continues because it constitutes the most important reason why the less industrially developed European countries put up with other European programmes that diminish their competitiveness, and it is the unspoken reason why so many new countries want to become members.

The CAP puts up the cost of food for EU consumers, thus increasing our costs and reducing our growth. It also depresses food prices worldwide, as subsidised European food exports deprive farmers in poorer countries of their livelihoods. This is precisely the wrong way round. Industrialised countries need low-cost workforces; agricultural countries need to provide their peasants with incomes. Both lose from the CAP.

The CAP is also a force for global protectionism. It has been estimated that the CAP is responsible for 85 per cent of the world’s agricultural subsidies.19 Not surprisingly, this prompts widespread resentment. Other countries, aware of this scandalous situation, are thus less willing to make compromises and resolve disputes.

The EU is not the only body which subsidises agriculture and it is not the only trade grouping which is inclined to protectionism. But on both counts it is certainly the most serious global offender. It has been estimated that the total annual cost of the CAP to the world economy is about $75 billion, of which two-thirds is borne by the Europeans in the form of higher prices, inefficient production and economic distortions. The rest falls on non-EU countries through lost agricultural export opportunities.20

Another expert study has found that the EU economy is almost as protected as it was a decade ago. Thus Professor Patrick Messerlin calculates that the cost of this protection, across the board, is equivalent to about 7 per cent of the European Union countries’ GDP, some $600 billion.21

The European tendency towards protection – demonstrated not just in the operation of the CAP but in numerous trade questions: films, bananas, and hormone-treated beef – is inherent in the European project itself. The reluctance to engage in open trade with the outside world only reflects a reluctance to accept the working of open markets at home. The EU and its predecessors were never, it should be remembered, interested primarily in free trade as such. They were and are a customs union – that is a group of countries which, while allowing free trade among themselves, charges a common set of tariffs to the rest of the world. The level of these tariffs has fallen sharply from an average of 12 per cent to 3 per cent over the last forty years as part of international trade negotiations. But the concept of global free trade is one to which the European countries have never been wedded, and never will be.

In theory, fundamental reforms of the CAP might, if they ever came about, remove one of the main reasons why the EU is such a force for protectionism. But the combination of high taxes, high levels of regulation and so high costs on the one hand, and the inflexibility resulting from a single currency and interest rate on the other, will in any case press Europe further down the protectionist path. Even within the framework set by the World Trade Organisation, there are many ways in which the EU could provide covert protection for its producers – such as through ‘anti-dumping’ measures. The EU’s trading partners must expect that it will do everything that it can to exploit such loopholes.

As the European superstate emerges on to the world scene, it will be keen to flex its muscles in economic as in other matters. It will seek to combat the ‘neo-liberalism’, i.e. the belief in free markets, which the French and German Finance Ministers so roundly denounced in Le Monde. It will try to substitute a more highly managed, i.e. more bureaucratic, model on international trade and finance. The Europeans will ultimately fail. But ‘ultimately’ can be a long time. Meanwhile, they spell trouble.

WIDER STILL AND WIDER …

In such circumstances it might seem odd that the EU is besieged by countries seeking membership. The shortcomings of the system are, after all, there for all to see. Yet enlargement is still the topic most talked about in European circles – at least in public.

Thus the alleged rationale of the Nice Summit in December 2000 was to prepare for further enlargement of European Union membership. It was argued that increasing the number of member countries from fifteen to twenty-seven required institutional reforms which would allow more streamlined decision-making, i.e. loss of the national veto.22 One can see how that fits the federalist agenda. What is increasingly contestable, however, is the sincerity with which EU countries view enlargement.

During the 1980s and most of the 1990s, Britain was in the forefront of those urging a widening of Community membership. As Prime Minister, I was keen to see the former dictatorships of Spain and Portugal given the opportunities and the stability required for democracy to flourish. Both I, and later John Major, were even keener to widen membership to include the former communist countries of Central and Eastern Europe, for very much the same reason. The extension of the frontiers of a free and prosperous Europe to the east was an integral part of the programme of a Europe of cooperating nation states which I had put forward in my speech at Bruges in 1988 – where I reminded my audience that ‘we shall [for which read ‘should’] always look on Warsaw, Prague and Budapest as great European cities’. After the fall of the Berlin Wall the following year this argument became even more cogent. To prolong the division of Europe by an economic tariff wall once the old political wall dividing West and East had crumbled was manifestly unjust.

Yet this is precisely what the European Community did. Far from welcoming in the former communist countries – with the exception of East Germany, which joined the West with hardly a by-your-leave – they were left to the tender mercies of agricultural dumping under Europe’s CAP and a niggling system of trade quotas. Twelve years after the collapse of communism, Poland, Hungary, the Czech Republic and the rest are still waiting.

Enlargement of the Community eastwards has traditionally been attractive to both the British and the Germans, but has been a good deal less so to the French and to the countries of Southern Europe. There is no great secret as to why this is so. Alongside our wish to see the ex-communist countries encouraged to create successful Western-style economies, British governments have hoped that, as the EU jargon has it, ‘widening’ would be at the expense of ‘deepening’. With the prospect of enlargement to include as many as twenty-seven members – counting in all the candidate countries – it seemed to us a plain impossibility to proceed with creating a federal superstate. The differences and potential conflicts between the members would be just too great.

For the Germans, extension eastwards had a rather different attraction and reflected other geopolitical interests. As a revealing CDU/CSU paper, ‘Reflections on Europe’, of 1 September 1994, put it:

The only solution which will prevent a return to the unstable pre-war system, with Germany once again caught in the middle between East and West [a somewhat eccentric description of the Third Reich in the thirties!], is to integrate Germany’s Central and Eastern European neighbours into the European post-war system and to establish a wide-ranging partnership with Russia … If European integration were not to progress, Germany might be called upon, or be tempted by its own security constraints, to try to effect the stabilisation of Eastern Europe on its own and in the traditional way. [Emphasis added]

By contrast, the French have, with the limited exception of Romania, not sought out friends or clients in Eastern Europe. Moreover, France and even more so Greece, Spain and Portugal have been extremely wary of the impact upon the CAP, and the valuable benefits they receive from it, of the introduction of new members with large, primitive agricultural sectors.

For as long as the Germans continued to be enthusiastic about the entry of the ex-communist countries, some (albeit snail-paced) progress was made. But it is now apparent that resistance within Germany to expansion is growing. The German EU Commissioner for Enlargement, Günter Verheugen, has, for example, suggested that a referendum may be needed in Germany before enlargement goes ahead. German public opinion appears to be quite strongly opposed to the prospect of free entry for goods and services and, above all, workers from the East. In particular, hostility to early full membership for Poland has hardened.23

The present British government is, it seems, still strongly in favour of early expansion. But one may question whether this policy still makes much sense. All that has been seen of developments within the European Union over the last decade confirms that ‘deepening’ – that is the persistent accumulation of more and more powers by European institutions to override national wishes and interests – will go ahead, however much membership ‘widens’. Indeed, as was shown by the decisions made at Nice, even the vague prospect of enlargement provides the excuse for a raft of new measures of centralisation. Similarly, the long-standing British hope that the need to absorb new members would lead to fundamental reform of the European Union’s finances, above all the CAP, shows every sign of proving illusory.

For all these reasons, I am now unpersuaded by the case for further EU expansion. And although I fully understand the mix of historical, political and economic factors which account for the enthusiasm of the Central and East European countries for full membership, I also doubt whether they are well-advised to press for it on the terms available. Since leaving office, I have had the benefit of many frank and friendly (and that in the proper not diplomatic sense) conversations with senior political figures from these countries. Most of them, when pushed, are uneasy about what the EU may entail. Having endured the best part of half a century living under socialist bureaucracy, and seeing their national identities and rights overridden, they are not at all keen to be ruled from Brussels. Furthermore, although many of them are deeply uneasy about instability to the east, and so still want the reassurance offered by EU (as well as NATO) membership, they have few illusions about the degree to which Europe is dominated by Germany. And that too worries them, though they are not likely to admit it publicly.

European politicians and officials are wont to talk rather patronisingly of how far the applicant countries have yet to go in modernising and opening up their economies in order to prepare for entry. But what really alarms the Europeans is their own lack of preparedness in the face of low-cost competition. If as part of their preparations for entry the former communist countries are willing to tie themselves up with all the rules and regulations imposed by Europe, they will finish up by giving away much of the competitive advantage they currently enjoy. At which point, presumably, their slower growth rates could be used in order to justify putting off membership once again. In my view, the applicant member countries would therefore be well-advised to consider long and hard whether full membership of the European Union is what they really want. Negotiating free-trade agreements with the EU and with the North American Free Trade Area (NAFTA) – and, indeed, with Britain (on which, see the next chapter) – might suit their interests better.

So I believe that:

The old arguments for expansion of EU membership no longer apply

The EU should be pressed to concede free-trade arrangements with the applicant countries

It should also be pressed to stop undermining these countries’ agricultural sectors by dumping its products at their farmers’ expense

The governments of the applicant countries would be wise to find other ways to modernise their economies and expand their markets – ones which do not involve loss of sovereignty, the acceptance of German dominance, or piling costs on their industries.

DEFYING DEMOCRACY

The EU-applicant countries ought also to be aware of the prevailing style of politics within the European Union. This style is difficult to sum up in one word: it is, in fact, an unusual mix of the authoritarian, the bureaucratic and the interventionist on the one hand, with the compromising, the uninspiring and the ineffective on the other. The European Union is for ever awash with plans, programmes and projects. But the result, more often than not, is an inefficient muddle. Its leaders’ eloquence is hyperbolic. But their decisions are characterised by horse-trading. Its ambitions to assert itself as a great power are unmatched. But the means at its disposal are few, and its attempts to play a role on the world stage have been universally embarrassing.

Perhaps the most significant shortcoming of the fledgling superstate is that it is not, will not be, indeed ultimately cannot be, democratic. This has nothing to do with the much discussed ‘democratic deficit’, which usually refers to the alleged disparity between the power wielded by the Commission and that wielded by the European Parliament. In fact, this is based on a false premise. The Commission and the Parliament share the same federalist agenda – and it is not democratic.

The real reason why there can be no functioning pan-European democracy is because there exists no pan-European public opinion. No matter how many attempts are made to create links between the political parties of different European countries, those parties know that they have to campaign upon, and that their fortunes will be determined by, national programmes and issues. The impact of European questions on such elections is most likely to be negative – when something that the European Union favours, such as open borders or more immigration, prompts popular anger.

It is a commonplace, but it is all too frequently ignored, that the European Union nations are extraordinarily deeply divided by language – no fewer than twelve main languages are widely spoken among the present members.24 Even those educated elites which speak foreign languages with reasonable facility may well be a long way from sharing the thought patterns of native speakers of those languages. And it is still the case that for the great majority of Europe’s population, ‘home’ is to be described in national, or local, not Continental terms.25

Конец ознакомительного фрагмента.

Текст предоставлен ООО «ЛитРес».

Прочитайте эту книгу целиком, купив полную легальную версию на ЛитРес.

Безопасно оплатить книгу можно банковской картой Visa, MasterCard, Maestro, со счета мобильного телефона, с платежного терминала, в салоне МТС или Связной, через PayPal, WebMoney, Яндекс.Деньги, QIWI Кошелек, бонусными картами или другим удобным Вам способом.