Полная версия

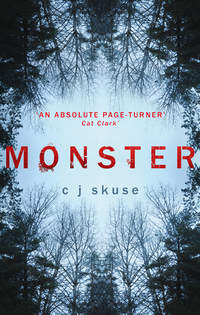

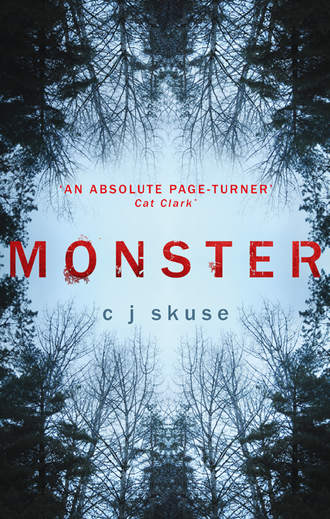

Monster: The perfect boarding school thriller to keep you up all night

‘You’re so full of shit, Dianna. That must be why your eyes are brown.’

It went on like this for a while. It always did. I finished my toast and a whole bowl of cornflakes, the war of words still raging around me. Eventually, Dianna was the first to run out of comebacks. ‘There’s two for you, Natasha.’

She held out two white envelopes. I took them both and saw the handwriting on the top one was Mum’s. A Christmas card from her and Dad. I didn’t recognise the second one. All around me, the chatter and clinking stopped.

When I looked up, all eyes around the table were on me except Regan’s. She was slowly chewing into a slice of toast while watching a money spider crawling over her free hand like it was the most interesting thing she’d ever seen. I ripped into the envelope and opened the letter.

Dianna was still hovering. ‘Anything important?’

‘Keep your beak out,’ said Maggie. ‘It’s none of your business.’

‘Uh, I think it is my business. I am Head Girl.’

‘Yeah, and don’t we know it?’

‘What does that mean?’

Maggie swigged her orange juice then licked her lips, slowly like a cat. ‘The only reason you wear that badge is cos you brown-tongued your way up Saul-Hudson’s arse. Everyone knows it should have been Nash who got Head Girl, not you.’

Dianna’s nostrils flared. ‘Well, Natasha fell at the final fence, didn’t she?’

‘Yeah, and why was that, do you think?’ I said. When I looked up, Dianna was staring at me. I opened my second letter.

It was a picture. Hand-drawn and coloured. Trees. Leaves. A large black monster with huge pointed teeth. Between its jaws it held a man’s body. The man had blond hair. There was red scribble all around the page. It was supposed to be the Beast. My brother. Blood.

I folded the letter back up and slotted it into the torn envelope. As I returned to my toast, I took a quick scan of the room, fixing my own face into a calm mask.

Clarice.

I picked her out again, three tables away, talking to Lauren Entwistle. She glanced across at me, and quickly glanced away again.

‘Who was your other one from?’ asked Maggie.

Choose your battles. Just ignore it.

‘Oh, just my nan. She can’t come and get me over Christmas. She’s away.’

‘Well, my mum’s still fighting a big divorce case in LA so she’s not going to be back any time soon either. And Dad’s in New York till whenever.’

‘Is your dad a lawyer too?’ I asked.

‘No, architect,’ said Maggie. ‘Something to do with that new thing they’re building on Wall Street or something, I dunno.’

‘One World Trade Center?’ I said, hardly believing it.

‘Summing like that.’

‘Wow,’ I said.

‘Sooo, we can have Christmas here on our own and totally let rip! No parents, no teachers, no Saul-Hudson ramming her big fat honk into our beeswax.’

‘Matron’ll be here though,’ I said.

She grimaced. ‘Yeah, but we can outrun her if we have to. Beeyatch.’

‘She’s been lovely since I heard about Seb,’ I said. ‘She asks me every morning if I’ve heard anything and whether I need to use the phone.’

‘Bless,’ said Maggie, unconvincingly. I knew how much she hated Matron and I didn’t wonder why. It was because Matron was usually the one who caught her out. Every single time.

‘There’s a Pup staying as well,’ I said, trying to think of the little girl’s name.

‘And I am,’ said a small voice. We both looked at the stern-looking girl with the plaits.

‘Why will you be here?’ asked Maggie, barely hiding her disdain.

‘I’m not allowed to go home for Christmas,’ Regan said, matter-of-fact. She pushed her glasses up her nose and dipped her head.

‘Why aren’t you allowed to go home?’

Regan swallowed down some cornflakes, leaving a milk drop on her chin. ‘I’m only allowed home one holiday a year, summer or Christmas. I went home in the summer so …’

‘… so you’re here for Christmas,’ I finished.

She nodded.

‘Oh peach parfait,’ groaned Maggie, her spoon clattering against her empty bowl.

‘Well, I guess we can make the best of it,’ I said, trying to find a bright side. ‘Plan a midnight raid on the kitchen or something.’

‘The devil is at your elbow, my child,’ said Maggie with an evil stare and a suggestive eyebrow wiggle.

I laughed.

Regan laughed too, but I don’t think she knew what she was laughing at. She still had a milk drip on her chin. ‘We can go looking for the Beast that killed the man in the village.’

Maggie and I looked at her.

‘It would be better than sitting in the library. I spend a lot of time in the library.’

She didn’t say it to court pity. It was just a fact. And it was a fact with a subtext: spending time in the library was code for I have absolutely no friends.

‘I slept in there on Sunday night.’

‘Why?’ said Maggie. ‘All there is are encyclopedias and crappy books like Common Sense Beekeeping and Fun With Yarn. Not exactly party central.’

‘It’s warmer than the dorm. I was reading all the old school scrapbooks that the prefects of the past used to keep. About all the parties and plays. And the Beast.’

‘Oh yeah,’ Maggie laughed. ‘The Beast of Bathory? The stupidest mythical beast known to man. He only comes out in the winter when there’s no food around.’

‘He killed Mr Pellett in the village. He was a retired accountant. Lived up at The Old Apothecary.’

‘How do you know all this?’ said Maggie.

Regan tapped her nose. ‘I know a lot of things about the Beast of Bathory.’

I thought about my monster.

‘It’s just a scary story,’ I said. ‘The prefects have been telling the Pups ghost stories about the Beast of Bathory for generations.’

‘It’s more than a story. It’s real. A man died last week. It tore him to pieces. Two tourists went missing at the end of last summer and they haven’t been found.’ She fumbled with her collar and pulled out what looked like a necklace made from green garden twine. Right in the centre of it, there was a tooth. She showed it to us. ‘What do you think that is?’

‘Uh, looks like a tooth,’ said Maggie.

‘Looks like a dog’s tooth,’ I said.

‘I found it on the path between the Chapel and the Tree House. It’s one of the Beast’s incisors. Look at the size of it.’ The tooth was pretty big, about the length of a Post-it note. And about the same colour yellow too.

‘How did you make the hole?’ I asked her.

‘I did it in the CDT room. Imagine being ripped apart by a mouth full of them.’ She looked at the tooth like it was a naked picture of Ryan Gosling.

Maggie threw me a look, grabbing a last piece of burnt toast from the rack. ‘It’s total and utter rubbish. It’s probably plastic.’

‘No it’s not,’ said Regan. ‘People have seen it.’ She looked directly at me. I poured myself some more apple juice.

‘Witnesses swear it’s bigger than any beast you would get in a zoo. Twice the size of a tiger.’

Maggie stared at her with wide eyes, almost missing her mouth as her thickly buttered toast rose to greet it.

‘Loads of people have been killed in the past two years. And now Mr Pellett. There’ve been sightings recently. All at night.’

‘Convenient,’ said Maggie.

‘They say it has bright red eyes and growls like a tiger. It’s taken sheep from the farms. Everyone knows about it.’

Maggie laughed. ‘Bright red eyes. Don’t make me laugh. All boarding schools have these stories cos they’re so deathly dull. If you go up to the Blue Bathroom and say Adolf Hitler three times in the mirror, he appears and stabs you. And if you stand on the eleventh step of back stairs at eleven minutes past eleven on the eleventh month of the year, some weird leprechaun thing comes up out of the stairs and drags you down to hell.’

‘O’Leary’s ghost.’ I nodded. ‘Isn’t there one about the ghost girl of Grace’s Lake too? The one who sleepwalked there in the night and fell in, all tangled up in her bed sheets?’

Regan was stony-faced. ‘The Beast is real. People have died.’

We both looked at her. She really believed it.

‘I’ve seen tree trunks with scratches all up the bark. And I found something behind the Temple. Something awful. Do you want to see it?’

Just then, the bell dingalingalinggggged out in the corridor and Maggie and I both jumped out of our skins. Regan didn’t. She was just staring at us, waiting for an answer.

6 The Thing

While my form was busily black-bagging up their desk contents and lockers and cleaning the classrooms, I was sent to Mrs Saul-Hudson’s office for a ticking off about my attack on Clarice.

And that was all I got. A ticking off. I didn’t even receive a billion Blue Tickets for Tudor House or a detention or anything. Just a long monologue about how my parents would ‘have to be told’, how ‘fighting’s never the answer’ and how it was ‘understandable with the amount of stress I was under with my brother’s situation’.

And that was it.

The reason for my lack of punishment had little to do with what I’d done to Clarice, and everything to do with what I knew about the Saul-Hudsons. I was the secret keeper, you see. I’d been Mrs Saul-Hudson’s right-hand man for a long time. I had intimate knowledge of their private apartments and I knew stuff about them that they definitely wouldn’t want spreading around. Punishing me was a risk they couldn’t take, despite breaking a golden rule of the school.

Maggie was incensed.

‘You break a girl’s face and you get nothing? It’s so unfair! Not that Clarice didn’t deserve it or anything, cos she actually did, but you got nothing? Actual factual nothing?’

‘I know. This school is fundamentally flawed, Maggie,’ I told her as the break-time bell rang out in Long Corridor. ‘It’s the reason why you’re still here.’

‘Must be.’

The three of us hotfooted it across the frosty front lawn, up the flint steps into the valley where the Landscape Gardens began.

On hot summer weekends, being at Bathory School was heaven. I loved being a boarder. We could go outside to do our prep or take the three-mile walk into the tiny village of Bathory for ice cream, and we were sometimes allowed to swim in the pool to cool down. We could sit beneath the hazelnut tree on the Orangery lawn in our vests and shorts or play croquet.

But on winter days like this one, we were rarely let outside, except to walk Brody or go up to the Chapel for prayers and Sunday service. The swimming pool was frozen over and the hazelnut tree bare and stark without its leaves. Our noses glowed red and our breath left cloud trails on the air. I was still glad of something to take my mind off Seb. When I thought about him, I felt myself starting to lose my mind. Bathory just wasn’t the place to lose your mind. You might never get it back.

‘It’s just up here,’ said Regan, as she led Maggie and me towards the Temple, right at the top of the bank and up into the woods.

‘It’s not far now.’ She led us deeper in, where the tops of the trees were alive with birdsong.

‘Is this really worth it?’ said Maggie. ‘If we’re late, we’ll miss the fit work experience boy pruning the Quad hedge.’

The Quad was the square expanse of grass separating the French room from the corridor to the Science lab. ‘He’s finished,’ I said. ‘He’s not back again till the spring.’

‘Aw what?’ she groaned. ‘He was the one good thing about being here. Je suis desolate.’

‘He wasn’t that fit anyway.’

‘He bloody was. Didn’t you see him take his top off in the summer? Holy Mary Mother of Abs.’

‘There’s more to boys than abs and pecs.’

‘Not much more,’ said Maggie. ‘Don’t tell me you don’t get horny, Nash. You must crave it, we all do. Have the odd fantasy about Keith the bus driver or Mr Saul-Hudson in his golf trousers. Or out of them …’

I couldn’t even fake a laugh at that one.

‘No, I know who you’ve got the bubbles for,’ said Maggie. ‘Charlie the Shop Boy.’ She wiggled her eyebrows suggestively.

‘Shut up.’

Regan looked back at us blankly, and Maggie ‘explained’: ‘Nash fancies the boy who works at Bathory Basics.’

Regan carried on walking in silence.

Maggie gave the back of her head a dirty look. ‘God, what a sulk fest.’ She stopped to catch her breath. ‘Oh come on, let’s go back. Bet you any money she’s taking us to So-Not-Worth-It-Town.’

‘We won’t know until we get there, will we?’ I said, picking up the pace.

Pretty soon, we were up in the highest part of the valley, where a sloping dirt track, worn by centuries of wooden carts transporting ice from Grace’s Lake and Edward’s Pond up to the now overgrown icehouse, led to the Temple.

Maggie and I stopped walking. Pigeon-toed, Regan stumbled gingerly through the prickly bushes and crouched down behind the folly.

‘Come on,’ she whispered, beckoning us with her hand. Maggie looked at me then shrugged, and together we fought our way through. Partially hidden by rotting leaves and damp twigs was something that looked like a long knobbly stick covered in school Bolognese.

‘What the frig is that?’ said Maggie, batting away an errant branch. ‘That’s disgusting.’

I pulled my jumper cuffs down over my hands and shoved one across my mouth, trying to push images from my mind: my brother’s body, cut into pieces by guerrillas in the Colombian jungle.

Regan poked at the thing with a long twig. ‘I found it when I was exploring.’

‘You brought us all the way up here in the freezing cold to show us a sheep’s leg?’

‘It’s not a sheep’s leg,’ said Regan, standing up. ‘I don’t know what it is. What did you think you were coming to see?’

‘That’s not a sheep’s leg,’ I said behind my hand. Neither of them heard me.

‘I dunno,’ said Maggie. ‘A dead body or something? A monster’s cave? A tunnel back to civilisation? Not a frigging sheep’s leg.’

‘I told you it’s not a sheep’s leg,’ said Regan, moving closer and bending down to poke it with a twig. ‘I think it’s from a cow.’

‘I think it’s a spine,’ I said.

‘A SPINE?’ They both cried out, in a chorus of disgust.

‘Yes. Look at the bottom, there’s ribs sticking out of it. And the gunky stuff looks like intestines. It’s thick too.’

Regan levered up the end of it with her twig. ‘Is it … human?’

I shook my head. ‘No, it’s way too big. You’ve seen Bony Bonaparte in the Science lab. A human spine is much thinner than that. This looks to me like it’s come from a large animal. A cow or a horse, or something.’

‘But why is it here? Where has it come from?’ said Regan.

‘I don’t want to think about that,’ snapped Maggie, rubbing her arms. ‘I wanna go back inside, not stand here in the freezing cold, debating about some random bone. I told you this would be a big fat slice of nothing.’ Without another word, she started back through the bushes.

I waited for Regan. ‘I really think the Beast had something to do with this,’ she said.

‘It’s more likely a wildcat or something.’ I shrugged, although not even I believed that theory.

‘You haven’t seen it closely enough,’ said Regan. ‘Come here.’

I looked after Maggie, then moved closer and crouched down to look. ‘See?’ she said, pointing to the top of it.

‘Yeah.’ I put my jumper-cuffed hand up to my mouth again. ‘It stinks.’

‘But look at the bite mark on the top. Something bigger than a wildcat did that.’

‘A big wildcat?’ I said.

‘But what if it’s not?’ She stared hard into my eyes, like she could read the sell-by date under my skull. ‘You saw it on the playing field, didn’t you? That time in netball. I know you did. Aren’t you even curious about it?’

‘Regan, the Beast of Bathory is fictional, okay?’ I sighed, expelling a huge cloud of white air. ‘That’s why it’s in the myths and legends book in the library. It’s a story made up by some weirdo with an Abominable Snowman fetish.’

She wasn’t buying it. ‘Yes, but you hear about these sorts of things all the time, don’t you? Legends made up about beasts and monsters, just to keep people from going to places where they shouldn’t. Like Satan. There’s a school of thought that says he’s just made up to stop Christians from straying from the path of righteousness.’

I snickered nervously, no idea what I was actually snickering about. ‘Yeah, well, this conversation is getting a little too deep for me.’

‘Satan’s not the only one,’ said Regan, flicking a plait over her shoulder. ‘There are myths and legends in every culture, which came about to stop children being naughty or getting out of bed. The Bogeyman. Baba Jaga. Bloody Bones …’

A branch cracked somewhere in the woods.

‘What was that?’ I said, a frozen ache spreading all through my limbs.

‘Maybe it’s the Beast, come back for the spine?’

A distant ting-a-ling-a-ling tinkled in the distance. ‘Come on, that’s first bell.’ We were so far from Main House, I wanted to get going.

‘There has to be a reason why this spine is here and I want to know what it is,’ said Regan stubbornly. ‘Either it’s here because the Beast is real and it’s attacked a cow or a horse—or it’s here because someone wants us to think the Beast is real.’

I stood up. ‘Fine, whatever. I’m going back down now, okay?’

Regan followed me as we picked our way back through the bushes. In front of the Temple, we looked over the valley—I could just see the dot of Maggie walking beside the lake. I started back along the track, but I could tell Regan wasn’t following. When I looked back, she was just standing there, outside the Temple; her stare blank and cold, her eyes appearing almost black in the wintry light.

‘Regan?’

She didn’t move immediately—then, slowly and thoughtfully, she began walking towards me.

‘You know it’s real. There’s fear in your eyes,’ she said, as she passed me. Her own eyes were as dead as a shark’s.

I shivered as she left me there, wishing Maggie hadn’t been so far away.

7 Saw

Dad called me from Heathrow just before lunch, just to say I love you and We’ll be back soon. I could hear everyone back in the Refectory as I put the phone down, pulling their Christmas crackers and cheering as the turkeys were brought out to be carved by staff members at the ends of the tables. It was a joyous time. I just wished I’d felt it.

I rejoined the school midway through the turkey course. Christmas didn’t mean the food got any better at Bathory, despite all the little extras—roast potatoes (hard), organic carrots (mashed), peas (frozen), stuffing (God knows), pigs in blankets (raw) and figgy pudding and custard (grim) and though the sight of it all brought bile into my throat, I took a spoonful of each, knowing that if I didn’t there was nothing else to eat until dinner. The food at Bathory had always been bad. When I’d first arrived as an eight-year-old Pup, I’d been vegetarian. The first week, when I realised the vegetarian option was either a saucer of grated Smart Price cheese or a grey hard-boiled egg, I quickly switched back to meat to keep myself alive.

On a more positive note, Clarice Hoon hadn’t given me any more grief about Seb, aside from the odd snide look as I walked up Long Corridor. This I could handle. First to lose their cool loses the argument, Seb told me, and he was right. As always.

Midway through lunch, Mrs Saul-Hudson marched in and dragged Maggie out. It turned out she’d just had a phone call from a pilot at RAF Lyneham who’d done a fly-past the previous day, who’d kindly informed her that the school now had letters crudely daubed on its roof. Instead of assisting with the Christmas Fayre preparations, I gladly spent the afternoon helping Maggie to clean it off.

‘Why though? Why not expel me for this? It does NOT make sense!’ she shouted, as I scrubbed away at the second S in ‘SAVE US’. ‘Why keep giving me these stupid meaningless detentions? I mean, I’ve tried EVERYTHING to get out of this place. I’ve done it all …’

‘… even vandalised a listed building now,’ I added.

‘Yeah. I don’t know what more I can do,’ she cried. ‘Maybe I could get a boy in here. Yeah, that might do it.’

‘Why do you want to leave so badly?’ I asked. She didn’t answer immediately, so I pressed. ‘Seriously, you can tell me.’

‘I just wanna go home, that’s all. I don’t need an education.’

‘But they’ll only send you somewhere else, won’t they?’

‘Fine. Then maybe they’ll send me back to my old comp where I was happy and settled and didn’t have to wear this cheap scratchy boy-repeller.’ She loosened her tie like it was hurting her neck.

‘I’d miss you,’ I told her.

‘Yeah, right.’

‘I would. You’re the thing that’s keeping me going at the moment.’

‘Yeah, well, you’ll get over me eventually.’

She carried on scrubbing. I felt no padlock on my urge to tell her any more, so I just said it. ‘They’re paying double the fees.’

‘Huh? Who?’

‘Your parents.’

‘WHAT?’ she cried, standing up and slamming her scrubbing brush down on the flat roof where a thousand soap bubbles flew up into my face. ‘What do you mean? How? How do you know that? Are you joking me?’

I shook my head, wiping little flecks of foam from my nose and cheeks. ‘Your file was out on her desk when I was in there a few weeks ago. I wasn’t going through it or anything, I was just putting her cocoa down. And it was there, in your file. I read it.’

Maggie sat back down on the roof. ‘Double fees? That’s really why I’m still here?’

I nodded. ‘There was a letter in the file, open, from your dad. I only read a bit, as I said, it was just there on the desk. He wants you to get your GCSEs here so you can go to a good Sixth Form or get a good apprenticeship when you leave. He doesn’t want you sponging off them like your sister does. And because you were kicked out of two other schools, Mrs Saul-Hudson agreed to keep you here, come what may. He thanked her for it. But that was it, that was all I read.’

Maggie shook her head. I sat down next to her. She looked beaten down. Flattened. Lost. ‘I can’t believe he’s done this. He knows how much I hate it here. I’ll run away.’

‘No you won’t.’

‘I will.’

‘You won’t, Maggie. You’d have to walk at least ten miles to the nearest train station.’

‘I’ll hitch.’

I looked at her. ‘Maggie, don’t.’

‘Why not? My parents clearly don’t give a toss. He’s leaving me here all Christmas, that’s how much he loves me. Git.’

‘They’re paying £18,000 a term so you can get your education, Maggie. I’d say they love you a hell of a lot. And anyway, I’m here all Christmas too so it won’t be so bad.’

‘They’re sadists. Actual, factual sadists.’

‘Why do you hate it here so much?’

‘Why?’ she repeated. ‘Look around you, Nash. We’re in the middle of actual NOWHERE.’

I shrugged, looking around us beyond school land towards the moors and the hillsides dusted with icing sugar snow and spindly black trees. Coupled with the cinnamon smells rising up from the Fayre and the tinkling of a carol from somewhere, it felt like we were in a scene from a Christmas card. It was stunning. ‘That’s not so bad. It’s quite beautiful, don’t you think? Look at the snow on the hills, on the trees.’

‘And I hate nature.’

‘That can’t be the only reason you want to leave, the isolation.’

‘No,’ she said quietly. ‘The food’s crap as well.’

‘Yeah it is a bit, isn’t it?’ I grinned.

‘And …’

‘What?’

She went to tell me something then stopped herself. ‘It’s like you said—the place is “fundamentally flawed”. Why else would we be allowed up on this very old, probably very unsafe roof, to scrub tiles. No one gives a crap about Health and Safety here, do they? No one gives a crap about us.’