Полная версия

Eating for England: The Delights and Eccentricities of the British at Table

Eating for England

The Delights and Eccentricities of the British at Table

Nigel Slater

Copyright

Fourth Estate

An imprint of HarperCollinsPublishers Ltd. 1 London Bridge Street London SE1 9GF

www.harpercollins.co.uk

First published in Great Britain by Fourth Estate in 2007

Copyright © Nigel Slater 2007

Nigel Slater asserts the moral right to be identified as the author of this work

Some Photographs were unavailable for the electronic edition.

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the non-exclusive, non-transferable right to access and read the text of this ebook on-screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, down-loaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins ebooks

HarperCollinsPublishers has made every reasonable effort to ensure that any picture content and written content in this ebook has been included or removed in accordance with the contractual and technological constraints in operation at the time of publication

Source ISBN: 9780007199471

Ebook Edition © FEBRUARY 2012 ISBN: 9780007370047

Version: 2016-09-22

For D and P and in memory of M

Contents

Cover

Title Page

Copyright

Preface

In a Stew

Harvest Festival

The Lunchbox

Toblerone

The Kitchen Fusspot

Black Pudding

Cake Forks and Sticky Fingers

Shopping on the Internet – Couch Potatoes

The Biscuit Tin

The Digestive

Bread and Butter Pudding

Eating Soldiers

Lunch on a Bench

Combating that Sinking Feeling

The Coffee Percolator

Faggots and Gravy

The Naked Cook

Murray Mints

The Farmers’ Market – An Allotment for Wimps

Rhubarb and Custard

Fruit and Nut

The Setting of Jam

Oxo Cubes

Feeding the Elderly

Custard

A Custard

The Economical Cook

The Voucher Queen

A Cake Walk through Britain

The Gingerbread Wars

Shopping for Meat

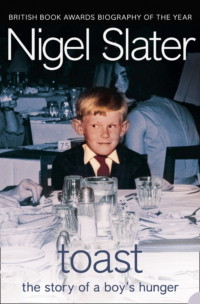

Toast – The Story of a Nation’s Hunger

Frogspawn and Nosebleeds

Stirring Jam into Your Rice Pudding – Or Not

The Nut Cutlet

A Child in the Restaurant – 1964

Toffees

The Midnight Feast

Jacob’s Club

Rubbernecking – The Lost Art of Celebrity-Spotting

The Wind in Your Face, a Fish in Your Bag

Summer Cooking

The Jaffa Cake

The Village Shop – The Font of All Knowledge and Fairy Soap

Tripe and Onions

Aga Toast

The Chocolate Digestive

The Rich Tea

Fudge

Ribena

Filling Your Bag

Old English Spangles

Fry’s Five Centres

Making Coffee

Breakfast

The Chocolate Bar – A Curiously British Obsession

‘My Name is Carol and I am a Chocoholic’

Your Life in Your Hands

Chopsticks at Dawn

Heinz Tomato Ketchup

Kia Ora

Tipping, as Only the Brits Know How

Jelly Babies

This Little Piggy

The Tight-Arse Cook

Washing Up

Mashed Swede

Ginger Cake

Cream Sponge

Eating in the Street – ‘I’ll Have That with Wings’

Throwing a Coffee Morning

The Cadbury’s Flake

A Teenager at the Table

Scones and the Sultana Problem

Bourbon Biscuits

Dairylea

Custard Creams

Modern Shopping

The Ritual of the KitKat

The Slightly Grubby Wholemeal Cook

Cyril’s Stew

Dripping – The Heart and Soul

A Taste of the Future

Floral Gums

Sherbet Lemons

Fray Bentos Steak-and-Kidney Pie

Eating Outdoors

Eating Pomegranates with a Pin

Mint Cracknel

Winter Food

The Jammie Dodger

Liquorice Sticks

Liquorice Wood

The Chocolate Finger and That One with the Hole In

A Good Roasting

Boiled Brussels Sprouts

Pontefract Cakes

Bath Chaps

Fancy Toast

White Food

Golden Mint Humbugs

Lardy Cake

The Expense Account Lunch

The Suburban Day Out Lunch

Quality Street

Branston Pickle

Paying the Price

A Third-Generation Fishmonger

The Work of Pixies

Gravy

The Extravagant Cook

That Old Black Magic

Brawn and Mustard

Trifle – A Social Indicator

The Best Biscuit of All?

Chocolate Limes

Sharing the Bill – The Weasel at the Table

Sweetness and Light

Scones on Harris

PG Tips

Robertson’s Golden Shred

The Specialist Shop

The Case for Clicks not Bricks

Frying Tonight

The Taste of the New

The Grow-Your-Own Cook

Pre-Jamie Man

Post-Jamie Man

If You Can’t Stand the Heat

Scratchings

Chocolate Éclairs

The Sweet Shop

The Berni Inn

Lunch

Crumpets, Pikelets, Muffins and Their Purpose

The Death of the Chocolate Cake

The Corner Shop – Our Little Life-Saver

Carving

Haggis, Tatties and Neeps

Gilding the Lily

Cake and Cheese

Everton Mints

Welsh Rarebit

Junket – The Clue is in the Name

Tunnock’s Teacakes

Poaching

The Cookery Hen

The Oh-I-Never-Measure-Anything Cook

How to Dress a Scone

Bisto

Colman’s Mustard

A Day at the Market

The British Lunch Out of Doors Then

The British Lunch Outdoors Now

A Litmus Test

The Victoria Sandwich

Gibbs After-Dinner Mints

The After Eight Mint

The Glorious British Chocolate Bar

Rest in Peace

The Supermarket Fish Shame

The Greengrocer – A Local Hero

A Nation of Old Boilers

Hotel Toast

Dick and Other Delights

Dead Man’s Leg

The Glue Factor

The Gingernut

Pear Drops

Acid Drops

Aniseed Balls

Butterscotch

A Drop or Two of Sauce

Midget Gems

Winter Teas – The Crumpet Season

A Muffin Worry

How to Open an English Muffin

A Log Fire Tea – Some Suggestions

Cupcakes at the Hummingbird

High Tea

The Packed Lunch

Werther’s Originals

The Polo Mint

Camp Coffee

Robinson’s Barley Water

Out of a Net and onto the Net

Marmite

The Organic Box

The Neat and Tidy Cook

The Cool, Modern Shopper Cook

‘Hands that Do Dishes’

Things Move On

The Death of the Cheese Board

Thick Toast

Best Friends

Treacle Tart

Coconut Ice

The Cream Cracker

Barley Sugars

Nut Toffee

Brown Sauce

Eating with the Wasps

A Summer Tea – A Few Polite Suggestions

Seaside Rock

A National Hero

Sarson’s Vinegar

The Pink Wafer

Keep Reading

About the Author

From the reviews of Eating for England

Also by Nigel Slater

About the Publisher

Preface

New York, late autumn, and I have just taken the short walk from Central Park to Carnegie Hall, where I am being interviewed for a radio show. It’s a bright, invigoratingly breezy day and I’m feeling confident. I know what I am to be interviewed about, and am pretty sure of my ground and even remain unfazed when, at the last minute, I find that the interview is going out live. As I say, I know my ground. And then comes the question, the one I wasn’t prepared for, the one where I am asked to describe British food to the listeners.

Do I tell them about the meltingly tender lamb from North Ronaldsay, the famous apple hat pudding with its tender suet crust, or the northern teacake known as the fat rascal? Do I have time to enthuse about the joys of medlar jelly, damson gin and the unpasteurised cheeses made down long leafy lanes in Dorset, Devon and Dumfries? Perhaps I should wax eloquent about Wiltshire bacon, sherry trifle, Christmas pudding, or steak-and-kidney pie with its crumbly pastry and dark and savoury filling? Will there be time to get in name-checks for Scottish heather honey, toasted teacakes, gooseberry fool and Caerphilly cheese? And will they let me squeeze in the glory that is a decent haggis, Welsh rarebit or Cornish pasty?

Or do I tell them the truth? That for every Brit eating our legendary roast beef and jam roly poly there are a million more tucking into Thai green curry and pepperoni pizza. That more people probably eat chocolate brownies than apple crumble and custard, and that it is now easier to find decent sushi than really good roast beef. Should I mention too that despite our love of all that is local, fresh, organic and ‘real’, we also have a list of edible icons more eccentric than anyone could ever imagine?

It is well known that we have been arguing for years whether gravy should be thick or thin, if pickled onions should be part of a ploughman’s lunch, or whether or not jelly belongs in a trifle. I wonder what they would also make of the fact that different counties argue about whether the jam or the clotted cream goes onto a scone before the other, or that more of us apparently use gravy browning than wine to capture the heavenly pan juices of our Sunday roast.

British food is, of course, about roast beef and Yorkshire pudding; it is about dressed crab, and roast chicken with nutmeggy bread sauce. It is about huge flakes of locally caught fish in crisp batter, eaten from the paper with the sea breeze in your hair, oysters from Whitstable as fresh as an icy wave, Eccles cakes with soft, flaky pastry, and the best bacon sandwich in the world. But it is also about Heinz tomato ketchup, brown sauce and Cadbury’s Fruit and Nut. The biggest names on the high street are not Betty’s tea rooms but Starbucks and Subway. There are more Pizza Expresses than traditional pie and mash cafés, and more McDonald’s than fish-and-chip shops. Looking at some people’s supermarket trolleys (oh, come on, you know you have), I sometimes wonder how you could define this country’s tastes at all. The internet, by the way, gives approximately 375,000 entries for roast beef and Yorkshire pudding, but over five million for that other great British invention, the Mars bar.

The fact of the matter is that our food culture is about both the gentle, buttercup-scented cheese made in a village barn the colour of honey, and the childish delight of unwrapping a foil triangle of Dairylea. It is indeed true that we make the most crumbly and agreeable oatcakes in the world, but it is the mass-produced cream cracker that has become the culinary icon. And despite producing some of the most delectable pork products in the world, we still love tucking into a bacon sandwich from a greasy-spoon café.

We have a greater wealth of good food in this country today than ever before. When I go to the market at the weekend for my cheeses, vegetables and meat, I am spoilt for choice by the food we produce, and often come home with a shopping bag almost too heavy to lift. In that respect I think of myself as being truly attached to the locally-produced, the artisan-crafted and the handmade. So how come I also regard a plain chocolate digestive biscuit as one of the finest things this country has to offer?

The British have a curiously broad culinary identity. Only the naïve would now try to pin us down as a meat-and-two-veg culture. You could argue that ours is a rich and multiculturally exciting cuisine, reflecting a country of diverse tastes and open minds; but equally, it sometimes looks as if we are in a state of total culinary shambles. If we hold up a pot of tea with scones and jam as a national treasure (and I do), then why is it easier to find an Italian cappuccino and an all-American blueberry muffin on most high streets? And how is it that while the French almost called a national strike over any suggestion of using pasteurised milk in their cheeses, the Spanish all but went to war to protect their fishing, and Italy gave its Parmesan cheese internationally protected status, we British only truly went into meltdown over the repackaging of the KitKat? (And quite rightly, if you ask me.)

What the French or the Italians may get excited about is very, very different from what most of us in these islands are likely to hold dear. We hold a candle for everything from black pudding to the Custard Cream, feel more fondness for Murray Mints than for a decent veal chop, and are rather partial to leaving our most famous food for the tourists while we ourselves tuck into something from another culture.

This book is my portrait of this curious, often contrary culture, from our adoration of the kipper, the pork scratching and the Rowntree’s Fruit Gum to our inability to tip properly in restaurants. I feel that while the heroic efforts of our artisan food-makers have been well catalogued (though still far from well enough patronised), all too little attention has been paid to the food that most of us either actually eat, or at least carry a certain lingering affection for. Eating for England is simply a personal celebration of the food this nation cherishes, the rituals we observe, the curious and even eccentric thing that is the British and their food.

Nigel Slater

June 2007

In a Stew

The British make an everyday stew with cubes of beef, carrots, parsnips and onions. They pour a jug of water over it, tuck in a bay leaf and leave it in the oven to do its own thing for four hours. What emerges is grey, meltingly tender meat and gently flavoured broth, comforting and unapologetic in its frugality. It tastes of nothing but itself.

There are formal similarities between our national stew and those of Europe and its neighbours. The knee-jerk shopping list of onions and carrots; the introduction of some sort of benevolent liquid; the convenient habit of leaving the simmering ingredients unattended for an hour or more, are common to all. The southern French recipe will be made with beef rump, its obligatory onions softened in the bright, fruity oil of the region, and its seasonings of orange peel, mauve garlic, sun-scarred tomatoes and, possibly, lavender inevitably breathe sunshine into its soul. Further north, as you potter down the Rhone valley during the vendange in October, your day might be punctuated by a paper-tablecloth lunch of cubed beef that has simmered since breakfast with shallots, strips of unsmoked bacon, rosemary and mushrooms in an inky violet-red wine.

The Italians, though less likely to use alcohol, will add body to the simplest stew of boneless brisket with the introduction of a whole, cheap tongue and a gelatinous, collagen-rich cotechino sausage. The juices that surround the meat may look more like ours than do the mahogany-hued French or the paprika-stained Spanish versions, but will be silkily limpid in the mouth because of the goodness distilled from both tongue and cotechino. If a British stew is rich at all, it will be because of the early addition of flour to the meat, the thickening qualities of which give the impression of suavity but add nothing in terms of flavour.

And then, just as we Brits abandon our stew to the hungry hordes gathered at the table, the cooks of other nations will add a vital snap of freshness and vigour to lift it from its sleepy brown torpor: the French their persillade of vivid parsley, anchovy and lemon; the Moroccans a slick of tongue-tingling harissa the colour of a rusty bucket; and the Italians a pool of hot, salty salsa verde pungent with basil, mustard and mint. The Catalans, who, as history would have it, are unlikely ever to spend a penny more than necessary, will even so stir in a final topping of garlic, breadcrumbs, almonds and bitter chocolate fit for royalty.

The basics are familiar in every place; it is only the details, or lack of them, that introduce into the British version the unmistakable air of culinary poverty. Their stews are the colour of mud, blood or ochre pigment, and taste of thyme and garlic, orange and almonds, basil and lemon. Ours is the colour of washing-up water and smells of old people.

Harvest Festival

Apart from Midnight Mass on Christmas Eve, and the time the BBC came to film Songs of Praise, my family never really went to church. Yet my father and stepmother always attended harvest festival, usually with me struggling behind with a heavy box of beans, a bag of carrots, and once a wooden crate of windfall apples from the garden.

The little stone church that sat at the bottom of the hill, and where my father’s funeral would eventually take place, would have marrows of various sizes, bundles of leeks tied with string, and bunches of dahlias the colour of wine gums stacked outside the door. Inside, loaves of bread and the produce of so many local gardens – pots of asters and bunches of chrysanthemums – were propped around the altar and tucked in the deep stone window ledges. The smell, of over-ripe damsons and yellow sunflowers, of freshly picked runner beans and home-made raspberry jam, was undercut with a sharp beery smell from the newly harvested hop fields (the church was in the middle of the Hereford–Ledbury–Bromyard hop triangle). I remember feeling that there could be nothing more beautiful than an English church decorated for harvest home. I can’t help thinking we still do harvest festival well, although it’s a pity that pensioners now insist on bringing tins of Heinz beans. A marrow would be much more pleasing, though presumably a bugger for the old dears to fit in their handbags.

I have always wondered why the sight of a place of worship decorated for harvest thanksgiving is so distinctly British, or at least not especially European. I recently clicked that it is the turning colour of the trees in the churchyards, the honey, orange and deep red leaves, that make the festival so much prettier than it is in warmer climates, whose trees are mostly evergreen (save possibly Vermont, though I have never been there). It is the whole picture, of harvested vegetables, bunches of spiky orange and pink dahlias, and the turning trees that make this a picture of Britain to treasure.

It hasn’t always been so. The only reason the Church got involved was to bring a little order to the rampant frolicking and drunkenness that traditionally accompanied the end of the harvest. It may have been a time for the farmers to say thank you to their workers, but it was also a time for those who toiled in the fields to get off their faces, fight and fornicate. Then a bit of decorum was brought into the proceedings in the shape of the church thanksgiving service. There’s the bloody Victorians for you.

The Lunchbox

There is a certain grace with which Indian women glide through the rice fields, lunchboxes in hand. It is as if you are witnessing a slow procession at a religious festival, rather than wives bringing lunch to their husbands. Of course a pink or saffron sari floating in the breeze against a lavender sky will always appear more romantic than one of us popping out to British Home Stores for a cheese and pickle.

School tuck boxes aside, the art of the packed lunch has very much fallen by the wayside. The oblong tin, its lid held secure by a rubber band, is a rare sight now, though the treasures it contains are just as fascinating. By rights the home-made sandwiches should be accompanied by a slice of cake and an apple, though things have moved on a bit. If there is a modern designer version, presumably without the rubber band, it may well now be filled with stuffed focaccia and a little pot of blueberries, or maybe a slice of panettone. The utterly essential Tunnock’s Caramel Wafer has no doubt been replaced by one of Ms Gillian McKeith’s bowel-opening fibre bars. Hardly ideal, I would have thought, when you are walking through the Yorkshire Dales.

Toblerone

I have always found a bar of Toblerone almost as difficult to conquer as the mountain peaks its design so clearly represents. But beyond the familiar rattle of the bar in its triangular box, and the ragged job you inevitably make of unwrapping it from its foil, lies a quietly classic piece of confectionery quite unlike any other.

Whatever way you try to tackle it, a Toblerone is an obstacle course. It can take a few attempts to break a triangle from the nougat-speckled bar without actually hurting your knuckles, and then, when you finally do, you have a piece of pointy chocolate slightly too big for your mouth. You bite with your front teeth and find the chocolate barely gives, so you attempt to snap it with your fingers, and find that doesn’t work either. The only thing left is to pop the whole lump in your mouth and suck.