Полная версия

From the Dust Returned

“Ann!”

“Tell him to leave!”

“Ann!”

But Ann had the bit in her mouth. “No, no, I hate him!”

I shouldn’t have left—even for a moment. Cecy poured her mind into the hands of the young girl, into the heart, into the head, softly, softly. Stand up, she thought.

Ann stood.

Put on your coat!

Ann put on her coat.

March!

“No!”

March!

“Ann,” said her mother, “get on out there. What’s come over you?”

“Nothing, Mother. Good night. We’ll be home late.”

Ann and Cecy ran together into the vanishing summer night.

A room full of softly dancing pigeons ruffling their quiet, trailing feathers, a room full of peacocks, a room full of rainbow eyes and lights. And in the center of it, around, around, around, danced Ann Leary.

Oh, it is a fine evening, said Cecy.

“Oh, it’s a fine evening,” said Ann.

“You’re odd,” said Tom.

The music whirled them in dimness, in rivers of song; they floated, they bobbed, they sank, they rose for air, they gasped, they clutched each other as if drowning and whirled on in fans and whispers and sighs to “Beautiful Ohio.”

Cecy hummed. Ann’s lips parted. The music came out.

Yes, odd, said Cecy.

“You’re not the same,” said Tom.

“Not tonight.”

“You’re not the Ann Leary I knew.”

No, not at all, at all, whispered Cecy, miles and miles away. “No, not at all,” said the moved lips.

“I’ve the funniest feeling,” said Tom. “About you.” He danced her and searched her glowing face, watching for something. “Your eyes, I can’t figure it.”

Do you see me? asked Cecy.

“You’re here, Ann, and you’re not.” Tom turned her carefully, this way and that.

“Yes.”

“Why did you come with me?”

“I didn’t want to,” said Ann.

“Why, then?”

“Something made me.”

“What?”

“I don’t know.” Ann’s voice was faintly hysterical.

Now, now, hush, whispered Cecy. Hush, that’s it. Around, around.

They whispered and rustled and rose and fell away in the dark room, with the music turning them.

“But you did come,” said Tom.

“I did,” said Cecy and Ann.

“Here.” And he danced her lightly out an open door and walked her quietly away from the hall and the music and the people.

They climbed in and sat together in his open car.

“Ann,” he said, taking her hands, trembling. “Ann.” the way he said her name it was as if it wasn’t her name. He kept glancing into her pale face, and now her eyes were open again. “I used to love you, you know that,” he said.

“I know.”

“But you’ve always been distant and I didn’t want to be hurt.”

“We’re very young,” said Ann.

“No, I mean, I’m sorry,” said Cecy.

“What do you mean?” Tom dropped her hands.

The night was warm and the smell of the earth shimmered up all about them where they sat, and the fresh trees breathed one leaf against another in a shaking and rustling.

“I don’t know,” said Ann.

“Oh, but I know,” said Cecy. “You’re tall and you’re the finest-looking man in all the world. This is a good evening; this is an evening I’ll always remember, being with you.” She put out the alien cold hand to find his reluctant hand again and bring it back, and warm it and hold it very tight.

“But,” said Tom, blinking, “tonight you’re here, you’re there. One minute one way, the next minute another. I wanted to take you to the dance tonight for old times’ sake. I meant nothing by it when I first asked you. And then, when we were standing at the well, I knew something had changed, really changed, about you. There was something new and soft, something …” He groped for a word. “I don’t know, I can’t say. Something about your voice. And I know I’m in love with you again.”

“No,” said Cecy. “With me, with me.”

“And I’m afraid of being in love with you,” he said. “You’ll hurt me.”

“I might,” said Ann.

No, no, I’d love you with all my heart! thought Cecy. Ann, say it for me. Say you’d love him!

Ann said nothing.

Tom moved quietly closer to put his hand on her cheek.

“I’ve got a job a hundred miles from here. Will you miss me?”

“Yes,” said Ann and Cecy.

“May I kiss you goodbye?”

“Yes,” said Cecy before anyone else could speak.

He placed his lips to the strange mouth. He kissed the strange mouth and he was trembling.

Ann sat like a white statue.

Ann! said Cecy. Move! Hold him!

Ann sat like a carved doll in the moonlight.

Again he kissed her lips.

“I do love you,” whispered Cecy. “I’m here, it’s me you see in her eyes, and I love you if she never will.”

He moved away and seemed like a man who had run a long distance. “I don’t know what’s happening. For a moment there …”

“Yes?”

“For a moment I thought—” He put his hands to his eyes. “Never mind. Shall I take you home now?”

“Please,” said Ann Leary.

Tiredly he drove the car away. They rode in the thrum and motion of the moonlit car in the still early, only eleven o’clock summer-autumn night, with the shining meadows and empty fields gliding by.

And Cecy, looking at the fields and meadows, thought, It would be worth it, it would be worth everything to be with him from this night on. And she heard her parents’ voices again, faintly, “Be careful. You wouldn’t want to be diminished, would you—married to a mere earth-bound creature?”

Yes, yes, thought Cecy, even that I’d give up, here and now, if he would have me. I wouldn’t need to roam the lost nights then, I wouldn’t need to live in birds and dogs and cats and foxes, I’d need only to be with him. Only him.

The road passed under, whispering.

“Tom,” said Ann at last.

“What?” He stared coldly at the road, the trees, the sky, the stars.

“If you’re ever, in years to come, at any time, in Green Town, Illinois, a few miles from here, will you do me a favor?”

“What?”

“Will you do me the favor of stopping and seeing a friend of mine?” Ann Leary said this haltingly, awkwardly.

“Why?”

“She’s a good friend. I’ve told her of you. I’ll give you her address.” When the car stopped at her farm she drew forth a pencil and paper from her small purse and wrote in the moonlight, pressing the paper to her knee. “Can you read it?”

He glanced at the paper and nodded bewilderedly.

He read the words.

“Will you visit her someday?” Ann’s mouth moved.

“Someday.”

“Promise?”

“What has this to do with us?” he cried savagely. “What do I want with names and papers?” He crumpled the paper into a tight ball.

“Oh, please promise!” begged Cecy.

“… promise …” said Ann.

“All right, all right, now let be!” he shouted.

I’m tired, thought Cecy. I can’t stay. I must go home. I can only travel a few hours each night, moving, flying. But before I go …

“… before I go,” said Ann.

She kissed Tom on the lips.

“This is me kissing you,” said Cecy.

Tom held her off and looked at Ann Leary and looked deep, deep inside. He said nothing, but his face began to relax slowly, very slowly, and the lines vanished away, and his mouth softened from its hardness, and he looked deep again into the moonlit face held here before him.

Then he lifted her out and without so much as good night drove quickly down the road.

Cecy let go.

Ann Leary, crying out, released from prison, it seemed, raced up the moonlit path to her house and slammed the door.

Cecy lingered for only a little while. In the eyes of a cricket she saw the warm night world. In the eyes of a frog she sat for a lonely moment by a pool. In the eyes of a night bird she looked down from a tall, moon-haunted elm and saw the lights go out in two farmhouses, one here, one a mile away. She thought of herself and her Family, and her strange power, and the fact that no one in the Family could ever marry any one of the people in this vast world out here beyond the hills.

Tom? Her weakening mind flew in a night bird under the trees and over deep fields of wild mustard. Have you still got the paper, Tom? Will you come by someday, some year, sometime, to see me? Will you know me then? Will you look in my face and remember where it was you saw me last and know that you love me as I love you, with all my heart for all time?

She paused in the cool night air, a million miles from towns and people, above farms and continents and rivers and hills. Tom? Softly.

Tom was asleep. It was deep night; his suit was hung on a chair. And in one silent, carefully upflung hand upon the white pillow, by his head, was a small piece of paper with writing on it. Slowly, slowly, a fraction of an inch at a time, his fingers closed down upon and held it tightly. And he did not even stir or notice when a blackbird, faintly, wondrously, beat softly for a moment against the clear moon crystals of the windowpane, then, fluttering quietly, stopped and flew away toward the east, over the sleeping earth.

CHAPTER 6

Whence Timothy?

“And me, Grandmère?” said Timothy. “Did I come in through the High Attic window?”

“You did not come, child. You were found. Left at the door in a basket with Shakespeare for footprop and Poe’s Usher as pillow. With a note pinned to your blouse: HISTORIAN. You were sent, child, to write us up, list us in lists, register our flights from the sun, our love of the moon. But the House, in a way, did call and your small fists hungered to write.”

“What, Grandmère, what?”

The ancient mouth lisped and murmured and murmured and lisped …

“To start with, the House itself …”

CHAPTER 7

The House, the Spider, and the Child

The House was a puzzle inside an enigma inside a mystery, for it encompassed silences, each one different, and beds, each a different size, some having lids. Some ceilings were high enough to allow flights with rests where shadows might hang upside down. The dining room nested thirteen chairs, each numbered thirteen so no one would feel left out of the distinctions such numbers implied. The chandeliers above were shaped from the tears of souls in torment at sea five hundred years lost, and the basement cellar kept five hundred vintage-year bins and strange names on the wine tucked therein and empty cubbies for future visitors who disliked beds or the high ceiling perches.

A network of webways was used by the one and only spider dropping down from above and up from below so the entire House was a sounding spinneret tapestry played on by the ferociously swift Arach, seen one moment by the wine bins and the next in a plummeting rush to the storm-haunted garret, swift and soundless, shuttling the webs, repairing the strands.

How many rooms, cubicles, closets, and bins in all? No one knew. To say one thousand would exaggerate, but one hundred was nowhere near truth. One hundred and fifty nine seems an agreeable amount, and each was empty for a long while, summoning occupants across the world, yearning to pull lodgers from the clouds. The House was a ghost arena, yearning to be haunted. And as the weathers circled Earth for a hundred years, the House became known, and across the world the dead who had lain down for long naps sat up in cold surprise and wished for stranger occupations than being dead, sold off their ghastly trades and prepared for flight.

All of the autumn leaves of the world were shucked and in rustling migrations, hovered mid-America and sifted down to clothe the tree which one moment stood bare and the next was ornamented with autumn falls from the Himalayas, Iceland, and the Capes, in blushed colors and funeral-somber array, until the tree shook itself to full October flowering and burst forth with fruit not unlike the cut gourds of All Hallows.

At which time …

Someone, passing on the road in dark Dickensian storms, left a picnic basket by the front iron gate. Within the basket something wailed and sobbed and cried.

The door opened and a welcoming committee emerged. This committee consisted of a female, the wife, extraordinarily tall, and a male, the husband, even taller and gaunter, and an old woman of an age when Lear was young, whose kitchen boiled with only kettles and in the kettles soups better left from menus, and it was these three who bent to the picnic basket to fold back the dark cloth over the waiting babe, no more than a week or two old.

They were astonished at his color, the pink of sunrise and daybreak, and the sound of his respiration, a spring bellows, and the beat of his fisting heart, no more than a hummingbird’s caged sound, and on impulse the Lady of the Fogs and Marshes, for that is how she was known across the world, held up the smallest of mirrors which she kept not to study her face, for that was never seen, but to study the faces of strangers should something be wrong with them.

“Oh, look,” she cried, and held the mirror to the small babe’s cheek, and Lo! there was total surprise.

“Curse all and everything,” said the gaunt, pale husband. “His face is reflected!”

“He is not like us!”

“No, but still,” said the wife.

The small blue eyes looked up at them, repeated in the mirror glass. “Leave it,” said the husband.

And they might have pulled back and left it to the wild dogs and feral cats, save that at the last instant, the Dark Lady said “No!” and reached to lift, turn, and deliver the basket, babe and all, up the path and into the House and down the hall to a room that became on the instant the nursery, for it was covered on all four walls and topmost ceiling with images of toys put by in Egyptian tombs to nurse the play of pharaohs’ sons who traveled a thousand-year river of darkness and had need of joyous instruments to fill dark time and brighten their mouths. So all about on the walls capered dogs, cats; here too were depicted wheatfields to plow through to hide, and loaves of mortality bread and sheaves of green onions for the health of the dead children of some sad pharaoh. And into this tomb nursery came a bright child to stay at the center of a cold kingdom.

And touching the basket, the mistress of the winter-autumn House said, “Was there not a saint with a special light and promise of life called Timothy?”

“Yes.”

“So,” said the Dark Lady, “lovelier than saints, which stops my doubt and stills my fear, not saint, but Timothy he is. Yes, child?”

And hearing his name, the newcomer in the basket gave a glad cry.

Which rose to the High Attic and caused Cecy in the midst of her dreams to turn in her tidal sleep and lift her head to hear that strange glad cry again which caused her mouth to shape a smile. For while the House stood strangely still, all wondering what might befall them, and as the husband did not move and the wife leaned down half wondering what next to do, Cecy quite instantly knew that her travels were not enough, that beginning now here, now there with seeing and hearing and tasting there must be someone to share it all and tell. And here the teller was, his small cry giving announcement to the fact that no matter what might show and tell, his small hand, grown strong and wild and quick, would capture it and scribble it down. With this assurance sensed, Cecy sent a gossamer of silent thought and welcome to reach the babe and wrap it round and let it know they were as one. And foundling Timothy so touched and comforted gave off his crying and assumed a sleep that was a gift invisible. And seeing this, the frozen husband was given to smile.

And a spider, heretofore unseen, crept from the blanketings, probed all the airs about, then ran to fasten on the small child’s hand as nightmare papal ring to bless some future court and all its shadow courtiers, and held so still it seemed but stone of ebony against pink flesh.

And Timothy, all unaware of what his finger wore, knew small refinements of large Cecy’s dreams.

CHAPTER 8

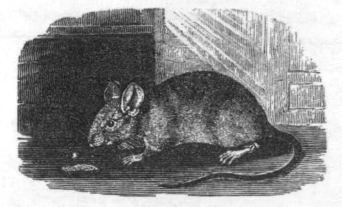

Mouse, Far-Traveling

As there was one spider in the House, there had to be—A singular mouse.

Escaped from life into mortality and a First Dynasty Egyptian tomb, this small ghost rodent at last fled free when some curious Bonaparte soldiers broke the seal and let out great gusts of bacterial air which killed the troops and confused Paris long after Napoleon departed and the Sphinx prevailed, with French gun-pocks in her face, and Fate splayed her paws.

The ghost mouse, so dislodged from darkness, excursioned to a seaport and shipped out with but not among the cats for Marseilles and London and Massachusetts and a century later, arrived just as the child Timothy cried on the Family’s doorstep. This mouse rattle-tapped under the doorsill to be greeted by an alert eight-legged thing, its multiple knees fiddling above its poisonous head. Stunned, Mouse froze in place and wisely did not move for hours. Then, when the arachnid papal ring presence tired of surveillance and departed for breakfast flies, Mouse vanished into the woodwork, rattle-scratched through secret panelings to the nursery. There, Timothy the babe, in need of more fellows no matter how small or strange, welcomed him beneath the blanket to nurse and befriend him for life.

So it was that Timothy, no saint, grew and became a young manchild, with ten candles lit on his anniversary cake.

And the House and the tree and the Family, and Great Grandmère and Cecy in her attic sands, and Timothy with his attendant Arach in one ear and Mouse on his shoulder and Anuba on his lap, waited for the greatest arrival of all …

CHAPTER 9

Homecomimg

“Here they come,” said Cecy, lying there flat in the High Attic dust.

“Where are they?” cried Timothy near the window, staring out.

“Some of them are over Europe, some over Asia, some of them over the Islands, some over South America!” said Cecy, her eyes closed, the lashes long, brown, and quivering, her mouth opening to let the words whisper out swiftly.

Timothy came forward upon the bare plankings and litters of papyrus. “Who are they?”

“Uncle Einar and Uncle Fry, and there’s Cousin William, and I see Frulda and Helgar and Aunt Morgianna, and Cousin Vivian, and I see Uncle Johann! Coming fast!”

“Are they up in the sky?” cried Timothy, his bright eyes flashing. Standing by the bed, he looked no more than his ten years. The wind blew outside; the House was dark and lit only by starlight.

“They’re coming through the air and traveling along the ground, in many forms,” said Cecy, asleep. She lay motionless and thought inward on herself to tell what she saw. “I see a wolflike thing crossing a dark river—at the shallows—just above a waterfall, the starlight burning his pelt. I see maple leaves blowing high. I see a small bat flying. I see many creature beasts, running under the forest trees and slipping through the highest branches; and they’re all heading here!”

“Will they be here in time?” The spider on Timothy’s lapel swung like a black pendulum, excitedly dancing. He leaned over his sister. “In time for the Homecoming?”

“Yes, yes, Timothy!” Cecy stiffened. “Go! Let me travel in the places I love!”

“Thanks!” In the hall, he ran to his room to make his bed. He had awakened at sunset, and as the first stars had risen, he had gone to let his excitement run with Cecy.

The spider hung on a silvery lasso about his slender neck as he washed his face. “Think, Arach, tomorrow night! All Hallows’ Eve!”

He lifted his face to the mirror, the only mirror in the House, his mother’s concession to his “illness.” Oh, if only he were not so afflicted! He gaped his mouth to show the poor teeth nature had given him. Corn kernels, round, soft, and pale! And his canines? Unsharpened flints!

Twilight was done. He lit a candle, exhausted. This past week the whole small Family had lived as in their old countries, sleeping by day, rousing at sunset to hurry the preparation.

“Oh, Arach, Arach, if only I could really sleep days, like all the rest!”

He took up the candle. Oh, to have teeth like steel, like nails! Or the power to send one’s mind, free, like Cecy, asleep on her Egyptian sands! But, no, he even feared the dark! He slept in a bed! Not in the fine polished boxes below! No wonder the Family skirted him as if he were the bishop’s son! If only wings would sprout from his shoulders! He bared his back, stared. No wings. No flight!

Downstairs were slithering sounds of black crepe rising in all the halls, all the ceilings, every door! The scent of burning black tapers rose up the banistered stairwell with Mother’s voice and Father’s, echoing from the cellar.

“Oh, Arach, will they let me be, really be, in the party?” said Timothy. The spider whirled at the end of its silk, alone to itself. “Not just fetch toadstools and cobwebs, hang crepe, or cut pumpkins. But I mean run around, jump, yell, laugh, heck, be the party. Yes!?”

For answer, Arach spun a web across the mirror, with one word at its center: Nil!

All through the House below, the one and only cat ran in a frenzy, the one and only mouse in the echoing wall said the same in nervous graffiti sounds, as if to cry: “The Homecoming!” everywhere.

Timothy climbed back to Cecy, who slept deep. “Where are you now, Cecy?” he whispered. “In the air? On the ground?”

“Soon,” Cecy murmured.

“Soon,” Timothy beamed. “All Hallows! Soon!”

He backed off studying the shadows of strange birds and loping beasts in her face.

At the open cellar door, he smelled the moist earth air rising. “Father?”

“Here!” Father shouted. “On the double!”

Timothy hesitated long enough to stare at a thousand shadows blowing on the ceilings, promises of arrivals, then he plunged into the cellar.

Father stopped polishing a long box. He gave it a thump. “Shine this up for Uncle Einar!”

Timothy stared.

“Uncle Einar’s big! Seven feet?”

“Eight!”

Timothy made the box shine. “And two hundred and sixty pounds?”

Father snorted. “Three hundred! And inside the box?”

“Space for wings?” cried Timothy.

“Space,” Father laughed, “for wings.”

At nine o’clock Timothy leaped out in the October weather. For two hours in the now-warm, now-cold wind he walked the small forest collecting toadstools.

He passed a farm. “If only you knew what’s happening at our House!” he said to the glowing windows. He climbed a hill and looked at the town, miles away, settling into sleep, the church clock high and round and white in the distance. You don’t know, either, he thought.

And carried the toadstools home.

In the cellar ceremony was celebrated, with Father incanting the dark words, Mother’s white ivory hands moving in the strange blessings, and all the Family gathered except Cecy, who lay upstairs. But Cecy was there. You saw her peering from now Bion’s eyes, now Samuel’s, now Mother’s, and you felt a movement and now she rolled your eyes and was gone.

Timothy prayed to the darkness.

“Please, please, help me grow to be like them, the ones’ll soon be here, who never grow old, can’t die, that’s what they say, can’t die, no matter what, or maybe they died a long time ago but Cecy calls, and Mother and Father call, and Grandmère who only whispers, and now they’re coming and I’m nothing, not like them who pass through walls and live in trees or live underneath until seventeen-year rains flood them up and out, and the ones who run in packs, let me be one! If they live forever, why not me?”