полная версия

полная версияThe Arena. Volume 4, No. 24, November, 1891

New mill at New Bedford, Mass., for the manufacture of fine yarn, on account of the high tariff on this grade of goods.

New mill at Dallas, Texas. (15,000 spindles.)

New cotton mill at Monroe, La. (Capital, $200,000.)

New mill at Austin, Texas, to cost $500,000.

Cotton factory at New Iberia, Ky.

Stock company (capital, $500,000) at Atlanta, Ga., to work the fibre of the cotton stalk into warp for cotton bales.

New cotton factory at Abbeville, S. C.

New cotton factory at Summit, Miss.

Jean pants and cotton sack factory, at Louisiana State Penitentiary.

New cotton mill at Moosup, Conn.

New cotton mill at Wolfboro, N. H. (Capital, $800,000.)

Bagging mills at Sherman, Texas.

Cotton batting factory at Columbia, S. C. (Capital, $40,000.)

Cotton mill at Greenville, Tenn.

Cotton tie factory at Selma, Ala.

WOOLLENHarvey’s carpet mills at Philadelphia, Pa.

Arlington mills at Lawrence. (Worsted—500 hands.)

Knitting mills at Cohoes, N. Y.

Knitting mills at Bennington, Vt. (75 hands.)

Woollen mill at Barre Plains near Worcester. (Fancy Cassimeres.)

Crescent yarn and knitting mills at New Orleans, La. (Capital, $75,000. Capacity 500 dozen of hose per day.)

Wytheville Woollen & Knitting Co. at Wytheville, W. Va. (Capital, $30,000.)

Yarn factory at Athens, S. C.

Coat factory at Ellsworth, Me. (Employs 75 to 100 hands.)

Woollen mills at Lynchburg, Va.

Woollen manufactory at Philadelphia, Pa.

Knitting mill (200 x 90) at Cohoes, N. Y.

Woollen factory at Worcester, Mass.

Knitting mill at Raleigh, N. C. ($25,000.)

Knitting mill at Pittsboro, N. C.

Cotton and woollen yarns at Catonsville, Md. (Capital, $10,000.)

Yarn factory at Lambert’s Point, Va. (Capital, $25,000.)

New factories of the Merrimack Coat and Glove Co., at Waban, N. H.

Knitting mill at Rockton, N. Y.

Yarn manufactory at Winsted, Conn.

Worsted manufactory at Woonsocket, R. I.

POTTERY AND GLASSChattanooga Pottery Co. Pottery mills at Millville, Tenn.

Glass factory to manufacture glass jars and bottles at Middletown, Indiana.

Window glass factory at Baltimore, Md.

Glass manufactory at Fostoria, Ohio. (125 persons operate 12 pots.)

Parmenter Mfg. Co. at East Brockfield, Mass. (Capital, $250,000.)

Glass manufactory at Grand Rapids, Mich.

American Union Bottle Co. Glass works at Woodbury, N. J.

A. Busch Glass Works at St. Louis, Mo.

Large glass plant at Denver, Col., by Chicago parties. (To employ between 300 and 400 men.)

Diamond Plate Glass Co., at Kokomo, Indiana. (Capacity, 5,500 ft. per day.)

New green glass factory at Alton, Ills. (To employ 425 men.)

Union Glass Co. at Malaga, N. J. (Capital, $100,000.)

Window Glass Co. of Pittsburgh, Pa. (Capital, $100,000.)

Window glass factory at Millville, N. J.

Glass manufactory at North Baltimore, Md. (Optical goods.)

PAPER AND PULPNew paper mill at Newport and Sunapee, N. H.

Otis Falls Pulp Co. at Livermore Falls, Me.

Mill for the manufacture of glazed hardware paper at Hemington, Conn.

Girvins Falls Pulp Co. of Concord, N. H. (Capital, $40,000.)

Paper mill at Manchester, Col.

New pulp mill at Howland, Me.

New pulp mill at Saxon, Wis.

New paper mill at Orono, Mo.

Large paper mill at Reading, Pa.

Brookside Paper Mill at Manchester, Conn.

Paper box factory at Richmond, Va. (Cost $7,000.)

Eureka Paper Mill Co. at Lower Oswego Falls, N. Y.

Shattuck & Babcock Co. of Depue, Wis. (Capital, $500,000.)

Pulp mill at Huntsville, Ala., by American Fibre Co. of New York. (Capital $80,000.)

IRON AND STEELLiberty Iron Co., at Columbia Furnace, Va. (Capital, $50,000.)

Basic steel plant, at Roanoke, Va. (Capital, $750,000. Capacity, 200 tons per day.)

Ashland Steel Co., at Ashland, Ky. (400 tons finished steel per day.)

Tredegar Steel Works, at Tredegar, Ala. (100 tons per day.)

Pennsylvania Steel Co., of Philadelphia. (Large ship building plant at Sparrow Point, on Chesapeake Bay.)

Pittsburg Malleable Iron Co., of Pittsburg, Pa. (Capital, $25,000.)

Beaver Tube Co., of Wheeling, W. Va. (Capital, $1,000,000.)

$1,000,000 stock company at Wheeling, W. Va., to develop coal and iron mines, etc.

New plant at Morristown, Tenn.

Iron furnace at Winston, N. C., by Washington and Philadelphia parties.

Buda Iron Works, of Buda, Ill. (Capital, $24,000. Railroad supplies and architectural iron work.)

Simonds Manufacturing Co., of Pennsylvania. (Iron and steel. Capital, $50,000.)

Iron City Milling Co., of Pittsburg, Pa. (Capital, $50,000.)

One hundred and twenty-five ton blast furnace, at Covington, Va.

Iron works at Jaspar, Tenn. (Capital, $30,000.)

Planing mill at Jaspar, Tenn. (Capital, $10,000.)

METAL WORKINGPeninsular Metal Works, of Detroit, Mich. (Capital, $100,000.)

Iron and brass foundry at Easton, Md.

Tinware factory at Petersburgh, Va.

Steel Edge Japanning & Tinning Co., at Medway, Mass. (Factory 800 x 60 feet.)

Horsch Aluminium Plating Co., of Chicago, Ill. (Capital, $5,000,000.)

Tin plate manufactory at Chicago, Ill.

MACHINERY AND HARDWARELynn Lasting Machine Co., at Saco, Me. (Capital, $50,000.)

Tin plate mill at Chattanooga, Tenn.

New plow factory at West Lynchburg, Va.

Machine works for Edison Electric Co., at Cohoes, N. H.

Haywood Foundry Co., at Portland, Me. (Capital, $150,000.)

Larrabee Machinery Co., at Bath, Me. (Capital, $250,000.)

Manufactory of mowers at Macon, Ga. (Capital, $50,000.)

Cooking stove manufactory at Blacksburg, S. C.

Nail, horse-shoe, and cotton tie factory at Iron Gate, Va.

Iron foundry and stove works at Ivanhoe, Va.

Wire fence factory at Bedford City, Va.

Nail mill and rolling mill with 28 puddling furnaces at Buena Vista, Va.

Car works by Boston capitalists at Beaumont, Texas. (Capital, $500,000.)

Car works plant at Goshen, Va.

Car works plant at Lynchburg, Va.

Nail mill at Morristown, Tenn.

Machine and iron works at Blacksburg, S. C. (Capital, $120,000.)

Eureka Safe & Lock Co. at Covington, Ky. (Capital, $50,000.)

Agricultural implements factory at Buchanan, Va. (Capital, $50,000.)

Tin can and pressed tinware factory at Canton, Md.

New hosiery factory at Charlotte, N. C.

$10,000 chair factory and $25,000 foundry and machine shop at Attalla, Ala.

Iron foundry and machine shops at Bristol, Tenn. (Capital, $25,000.)

Large skate factory at Nashua, N. H.

Stove Foundry & Machine Co. in Llano, Texas. (Cost, $100,000.)

Safety Package Co., at Baltimore, Md. (Capital, $1,000,000. To manufacture safes, locks, etc.)

Stove foundry at Salem, Va. (Cost $20,000. Capital, $60,000.)

Locomotive works plant at Chattanooga, Tenn. (Capital, $500,000.)

Fulton Machine Co., at Syracuse, N. Y. (Capital, $33,000.)

Chicago Machine Carving & Mfg. Co., at Chicago, Ill. (Capital, $50,000. To manufacture interior decorations, mouldings, etc.)

Standard Elevator Co., of Chicago, Ill. (Capital, $300,000.)

Wire nail mill at Salem, Va. (To employ over 100 men.)

TIN PLATEThe following firms are manufacturing tin-plate, or building new mills or additions to old ones for that purpose.

Demmler & Co., Philadelphia.

Coates & Co., Baltimore.

Fleming & Hamilton, Pittsburg.

Wallace, Banfield & Co., Irondale, Ohio.

Jennings Bros. & Co., Pittsburg.

Niedringhaus, St. Louis.

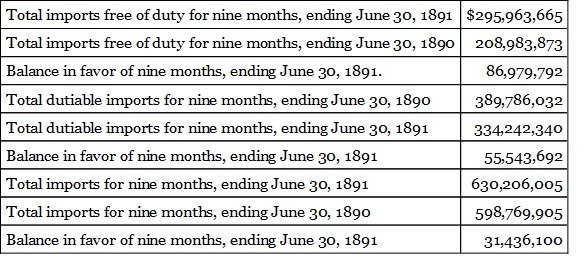

There is one other charge which was freely made against the tariff of 1890, that deserves a brief answer. It was said that the McKinley bill would stop trade with other countries, and that it raised duties “all along the line.”

A plain tale from the “Statement of Foreign Commerce and Immigration,” published by the Treasury Department for June, 1891, puts this accusation down very summarily.

BISMARCK IN THE GERMAN PARLIAMENT

I cannot pardon the historian Bancroft, loved and admired by all, for having one day, blinded by the splendors of a certain illustrious person’s career, compared an institution like the new German empire with such an institution as the secular American Republic. The impersonal character of the latter and the personal character of the former place the two governments in radical contrast. In America the nation is supreme—in Germany, the emperor. In the former the saviour of the negroes—redeemer and martyr—perished almost at the beginning of his labors. His death did not delay for one second the emancipation of the slave which had been decreed by the will of the nation, immovable in its determinations, through which its forms and personifications are moved and removed. In America the President in the full exercise of his functions is liable to indictment in a criminal court; he is nevertheless universally obeyed, not on account of his personality and still less on account of his personal prestige, but on account of his impersonal authority, which emanates from the Constitution and the laws. It little matters whether Cleveland favors economic reaction during his government, if the nation, in its assemblies, demands stability. The mechanism of the United States, like that of the universe, reposes on indefectible laws and uncontrollable forces. Germany is in every way the antithesis of America; it worships personal power. To this cause is due the commencement of its organization in Prussia, a country which was necessarily military since it had to defend itself against the Slavs and Danes in the north, and against the German Catholics in the south. Prussia was constituted in such a manner that its territory became an intrenched camp, and its people a nation in arms. Nations, even though they be republican, which find it necessary to organize themselves on a military model, ultimately relinquish their parliamentary institutions and adopt a Cæsarian character and aspect. Greece conquered the East under Alexander; Rome extended her empire throughout the world under Cæsar; France, after her victories over the united kings, and the expedition to Egypt under Bonaparte, forfeited her parliament and the republic to deliver herself over to the emperor and the empire. Consequently the terms emperor and commander-in-chief appear to be the synonyms in all languages. And by virtue of this synonymy of words the Emperor of Germany exercises over his subjects a power very analogous to that which a general exercises over his soldiers. Bismarck should have known this. And knowing this truth—intelligible to far less penetrating minds than his—Bismarck should in his colossal enterprise have given less prominence to the emperor and more to Germany. He did precisely the contrary of what he should have done. The Hohenzollern dynasty has distinguished itself beyond all other German dynasties by its moral nature and material temperament of pure and undisguised autocracy. The Prussian dynasty has become more absolute than the Catholic and imperial dynasties of Germany. A Catholic king always finds his authority limited by the Church, which depends completely on the Pope, whereas a Prussian monarch grounds his authority on two enormous powers, the dignity of head of the State, and that of head of the Church. The autocratic character native to the imperial dynasties of Austria is greatly limited by the diversity of races subjected to their dominion and to the indispensable assemblies of the diet around his imperial majesty.

But a king of Prussia, always on horseback, leader in military times, defender of a frontier greatly disputed by formidable enemies, whose soil looks like a dried-up marsh from which the ancient Slav race had been obliged to drain off the water, is required to direct his subjects as a general does an army. The intellectual, political, and military grandeur of Frederick the Great augmented this power and assured it to his descendants for a long epoch. It has happened to each king of Prussia since that time to perform some colossal task, grounded in an irreducible antinomy. Frederick William II. devoted himself to the reconciliation of Calvinism and Lutheranism as divided in his days as during the thirty years war, which was maintained by the heroism of Gustavus Adolphus, and repressed by the exterminating sword of Wallenstein. Frederick William IV. endeavored to unite Christianity and Pantheism in his philosophical lucubrations; the Protestant churches were deprived of their churchyards and statues by virtue of and in execution of Royal Lutheran mandates, as was also the Catholic Cathedral of Cologne, restored to-day in more brilliant liturgical splendor with the sums paid for pontifical indulgences. Bismarck did as he liked with the empire when it was ruled by William I., and did not foresee what would be the irremissible and natural issue of the system to which he lent his authority and his name. When William I. snatched his crown from the altar, as Charlemagne might have done, and clapped it on his head, repeating formulas suited to Philip II. and Charles V., the minister was silent and submitted to these blasphemies, derived from the ancient doctrine of the divine right of kings, because they increased his own ministerial power, exercised under a presidency and governorship chiefly nominal and honorary. But a thinker of his force, a statesman of his science, a man of his greatness, should have remembered what physiologists have demonstrated with regard to heredity, and should have known that it was his duty and that of the nation and the Germans to guard against some atavistic caprice which would strike at his own power. The predecessor of Frederick the Great was a monomaniac and the predecessor of William the Strong was a madman. Could Bismarck not foresee that by his leap backwards he ran the risk of lending himself to the fatal reproduction of these same circumstances, of transcendental importance to the whole estate, nay, to the whole nation? A king of Bavaria singing Wagner’s operas among rocks and lakes; a brother of the king of Bavaria resembling Sigismund de Caldéron by his epilepsy and insanity; Prince Rudolph showing that the double infirmity inherent in the paternal lineage of Charles the Rash and in the maternal line of Joanna the Mad continues in the Austrians; a recent king of Prussia itself shutting himself up in his room as in a gaol, and obliged by fatality to abdicate the throne of his forefathers during his lifetime in favor of the next heir, must prove, as they have done, what is the result of braving the maledictions of the oracle of Delphi, and the catastrophes of the twins of Œdipus with such persistency, in this age, in important and mature communities, which cannot become diseased, much less cease to exist when certain privileged families sicken and die. Not that I would ask people to do what is beyond their power and prohibited by their honor. There was no necessity, as a revolutionist might imagine, to overturn the dynasty. A very simple solution of the problem would have been to take against the probable extravagances of the Fredericks and Williams of Prussia the same precautions that were taken in England against the Georges of Hanover. These last likewise suffered from mental disorders. And so troubled were they by their afflictions that they were haunted by a grave inclination to prefer their native, though unimportant hereditary throne in the Germany of their forefathers to the far more important kingdom conferred on them by the parliamentary decision of England. But the English, to obviate this, showed themselves a powerful nation and respected the dynasty. Bismarck wished to make the king absolute in Prussia; he desired that a Cæsar should reign over Germany; and to-day the king and the Cæsar are embodied in a young man who has set aside the old Chancellor, and believes himself to have received from heaven, together with the right to represent God on this earth, the omnipotence and omniscience of God himself. Can it be doubted any longer that history reveals an inherent providential justice? To-day we see it unfold itself as if to show us that the distant perspectives of the past live in the present and extend throughout futurity.

II

Bismarck was on his guard against Frederick the Good, from whom a progressive policy was expected on account of his philosophical ideas, and a liberal and parliamentary government on account of the domestic influences which surrounded him. Knowing the humanitarian tendencies which sparkled in his disappointed mind, and the ascendency exercised over his diseased heart by the loved Empress Victoria, Bismarck availed himself of the terrible infirmity with which implacable fate afflicted the second Lutheran Emperor of Germany, and retained the imperial power in his own person, as though William I. were not dead. The enormous corpse of the latter, like that of Frederick Barbarossa, made a subject for analogous legends by German tradition, was replaced by another corpse, and in the decomposition consequent to his frightful infirmity, the unfortunate Frederick III. seems to have realized the title of a celebrated Spanish drama, “To Govern After Death” (Reinar Despues de Morir). All that he could do, when already ravaged by cancer, when the microbes of a terrible disease, like the worms of the sepulchre, were attacking and destroying him, was to open up a vista to timid hope, and to publish certain promises animated by an exalted humaneness, in spite of and unknown to the Chancellor who was not consulted in these declarations, which might be said to have descended from heaven on the wings of the angel of death. Bismarck went to and fro among the doctors, who naturally refused to declare the terrible disease mortal, and prepared to vanquish the moribund will of Frederick and the British notions of his widow, fearing that when the last breath of the imperial life had ceased the whole policy of Germany would have to be changed, as a scene in a theatre must be changed if it has been hissed. It was certain that there was as great a difference between the ideas of the Emperor William I. and those of Frederick III., separated by so brief a space, as between those of the Emperor Frederick Barbarossa and those of the Emperor Frederick II., his successor, after the long period of two hundred years had changed the capital features of the Middle Ages; the first was an unalloyed Catholic, notwithstanding his dissidences with the Guelph cities, and even with the Pope a stern Cæsar, like the good Roman Cæsars in time of war and defence, a veritable orthodox crusader, whose piety was concealed as in a colossal mountain whence he awaited the reconquest of outraged Jerusalem by the Christians; whereas the second was an almost Pantheistic poet and philosopher, whose Catholicity was mingled with Orientalism, who was equally given to the discussion of theological and of scientific questions, who followed the crusades in fulfilment of an hereditary tradition, who penetrated into the Basilica of the Holy Sepulchre by virtue of an extraordinary covenant with the infidel, and whose own beliefs were so cosmopolitan that they brought down a sentence of excommunication upon himself and of interdiction upon his kingdom. To Pope Innocent III., the former typified the Catholic emperor of the Middle Ages; Frederick II. appeared to him very much the same as in our days the Lutheran emperor appeared to Prince Bismarck, who took every possible precaution against the humanitarianism and parliamentarism of his dying pupil, and at the same time impelled his eldest son, the next heir to the crown, with all his influence and advice towards absolutist principles and reactionary propensities. No upright mind can ever forget the terrible desecration committed when, a few days before the death of his father, young William spoke of the empire as of a possession which it was to be understood he had already entered upon, and awarded the arm and head of his iron Chancellor the title of arm and head connatural with the Cæsarian institution. I know of no statesman in history who has given, under analogous circumstances, such proof of want of foresight as was given by Bismarck, comprehensible only if the body could assume the authority of the will, as did his, and if the intelligence could disappear, as did his, in an hydropic and unquenchable desire for power. Frederick, holding progressive ideas opposed to those of Bismarck and of William, would have greatly considered public opinion, and on account of that consideration would have perhaps respected, till the hour of his death, the Pilot, who, dejected by the new direction of public government, inferred that irreparable evil must result therefrom. When Maurice of Saxony trod on the heels of Charles V., whom he had defeated at Innsbruck, he was asked why he did not capture so rich a booty, and replied: “Where should I find a cage large enough for such a big bird?” Assuredly the conscience and mind of such a parliamentarian and philosopher as was Frederick III., must have addressed to him a similar question when he inwardly meditated sacrificing the Chancellor’s person and prescinding his power: “Where should I find a place outside the government for such a man, who would struggle under bolts and chains, making the whole state tremble in sympathy with his own agitation?” The experience and talent of Frederick, together with his respect for public opinion, led him to retain Bismarck at his post, subject only to some slight restrictions. But the Chancellor, in his shortsightedness, filled young William’s head with absolutist ideas; spurred and excited him to display impatience with his poor father; and when thus nurtured, his ward opened his mouth to satisfy his appetite, he swallowed up the Chancellor as a wild beast devours a keeper.

It was the hand of Providence!

III

The onus of blame devolves on Bismarck’s native ideas, which persisted in him from his cradle and resisted the revelations of his own personal experience as well as the spirit of our progressive age. In Bismarck there always subsisted the rural fibre of the Pomeranian rustic, in unison with the demon of feudal superstition and intolerance. In politics and religion he was born, like certain of the damned in “Dante’s Inferno,” with his head turned backwards by destiny. A quarrelsome student, a haughty noble, pleased only with his lands and with the privileges ascribed to the land owner, incapable of understanding the ideal of natural right and the contexture of parliamentary government, a Christian of merely external routine and formalist liturgy, he excited in the pusillanimous Frederick William, in his earliest counsels and during his early influence in the crisis of ‘48, a horror of democratic principles and progressist schools which led him to salute the corpses of his own victims, stretched out on the beds of his own royal palace, and to prostrate himself at the feet of Austria in the terrible humiliation of Olmutz, that political and moral Jena of the civil wars of the Germanic races. Very perspicuous in discerning the slightest cloud that might endanger the privileges of the monarchy and aristocracy, he was blind of an incurable blindness with respect to the discernment of the breath of life contained in the febrile agitations of new Germany, which discharged from its revolutionary tripod sufficient magnetism and electricity between the tempests, similar to those which flash, and thunder, and fulminate, from the summits of all the Sinais of all histories, to inflame a higher soul in any other more progressive society. The world cannot understand that he should have been perturbed by the external clamor of the revolution, when the idea of Germanic unity had become condensed in the soul of the nation, revealing itself by volcanic eruptions, like an incipient or radiant star; he could not understand how the Congress of Frankfort, cursed by him, foreshadowed the future, as though inspired by tongues of fire; and could not avail himself of all that ether whose comet-like violence, cooled down in the course of time, was to compose the new German nationality, and was to give it a greater fatherland where its inherent genial nature should glow and expand. In his shortsightedness, in his lack of progressive spirit, in his want of the prophetic gift, he imagined the principle of Germanic unity lost at Olmutz, like the principle of Italian unity at Novara, and ridiculed those who, certain of the immortality of such principles, foretold for both a Passover of Resurrection. He never understood the innermost essence and intrinsic substance of the principle, to which it owes its force and glory, sufficiently to adopt it, until he had witnessed its success in Italy, insulted in his speeches during the tempestuous dawn of the new common idea. It is on this account that I am rendered indignant by any comparison of Bismarck and Cavour, as I am rendered equally indignant by a comparison of Washington and Bonaparte. The father of the Saxon fatherland of America, and the father of the Italian fatherland in Europe, alike rendered worship to goodness, and never deviated from right in any degree; whereas the founders of French imperialism and of Germanic imperialism, much addicted to violence and very vain of their conquests, relinquished something as great and as fragile and sinister as the works produced by the genius of evil and outer darkness in all theogony. In the last years of the reign of Napoleon III., during the discussion of a message in the French Legislative Corps, Rouher extolled the public and private virtues of the emperor. My late lamented friend, Jules Favre, replied to him in a speech worthy of Demosthenes: “You may be content to be the minister of such a Marcus Aurelius; to such paltry dignities, I prefer the higher privilege of calling myself a citizen of a free country.” Bismarck preferred to maintain himself in power by the help of his kings—quite the contrary of what Gladstone does, who maintains his sovereign. Whom can he blame but himself? Emperors are accustomed to be ferocious with their favorites when they are weary of them. Just as Tiberius expelled Sejanus, just as Nero killed Seneca, just as John II. hanged D. Alvaro de Luna, just as Philip II. persecuted Antonio Perez till he died, just as Philip III. beheaded D. Rodrigo Caldéron, William II. has morally beheaded Bismarck, without any other motive than his imperial caprice. Sic volo, sic jubeo. So now will the Chancellor venture to present himself in parliament because he has been dismissed from the royal palace like a lackey? Quæ te dementia cæpit? When, after Waterloo, Napoleon, adopting the theatrical style of an Italian artiste, suitable to his tragical disposition, and repeating a few badly learned Plutarchesque phrases, suitable to the classical education of his age, asked the English, his enemies, to accord him hospitality, as in ancient times Themistocles might have petitioned his enemies the Persians, the English replied by sending him to St. Helena. Bismarck in disfavor and disgrace solicits an asylum from his enemies, the commons, whom he has never defeated, yet whom he has always disdained. And as the English condemned their troublesome guest to live on a gloomy little island, the electors condemn their repugnant petitioner to a second ballot. But the Chancellor will be completely undeceived; he possesses no qualifications whatever for the position he has chosen. An orator, a great orator, he one day failed to keep his pledged word, and the apostate word condemns him to never regain the executive power through its intervention. In the sessions of parliament he will resemble the plucked and cackling hen thrown by the Sophists into Socrates’ lecture-room. The admired Heine, so fertile in genial ideas, represented the gods of Phidias and Plato, besides being downfallen and vagabond, selling rabbit skins on the seashore, and being forced to light brushwood fires by which to warm their benumbed bodies during the winter nights. To-day the writers, salaried by Bismarck, known as reptiles, now turn on him, for a similar salary, the venomous fangs which he formerly aimed at his innumerable enemies. And yonder, in the parliament where formerly he strode in with sabre, and belt, and spurred boots, a helmet under his arm, a cuirass on his breast, he will now enter like a chicken-hearted charity-school boy, and that assembly which he formerly whipped with a strong hand, like school-boys, laughed at and caricatured in often brutal sarcasm, ridiculed at every instant, ignored in the calculation of the budget and the army estimates during long years, and sometimes divided and dispersed by his strokes, they, the rabble, will trample on him, like the Lilliputians on Gulliver, incapable of estimating his stature, and eternity and history will speedily bury him, not like a despot, in Egyptian porphyry, but like a buffoon.