полная версия

полная версияThe Continental Monthly, Vol 2, No 6, December 1862

Various

The Continental Monthly, Vol 2, No 6, December 1862 / Devoted to Literature and National Policy

THE UNION

III

On the 10th of April last, upon the recommendation of the President of the United States, Congress offered pecuniary aid to such States as would gradually abolish slavery within their limits. The colonization, from time to time, of the manumitted slaves, with their consent, by the Government, beyond our boundaries, was also contemplated as a part of the system. By the President's proclamation of September last, this offer is still made to loyal States, and practical measures suggested for carrying it into execution. As to the States persisting in rebellion after the close of this year, the President, as a military necessity, has announced a different measure, that is, general emancipation in all such States, with compensation only to loyal masters. Immediate emancipation of all slaves, with compensation for all, costing, as it would, twelve hundred millions of dollars, is now beyond the power of the Government, burdened as it is by an enormous and increasing debt. Nor was such a measure ever wise or expedient. That subject I will discuss hereafter, but will speak now of the plan proposed by the President, and sanctioned by Congress on the 10th of April last.

If this measure seems slow in securing total manumission and colonization, it would be progressive and certain. God works out the destiny of nations by no sudden or spasmodic action. His great and beneficent changes are generally slow and gradual, but when he wills destruction, it is sudden as the lightning's flash, the crash of the earthquake, or the sweep of the hurricane, marked by ruin and desolation. Would we avoid like disasters in solving this stupendous problem, we must follow, in humble faith, the ways of God, and thus by gentle, but constant and successive movements, reach the grand result.

History, however, exhibits a few extraordinary cases, in which man, as an instrument in the hands of Providence, sometimes punishes great crimes, eradicates great evils, and accomplishes great national reforms by acts as sudden as the devastating career of the tempest in sweeping away pestilential vapors. Such may be the case with the revolted States, if they should persist in this wicked rebellion beyond the close of the period of solemn warning.

The coming year may be the great crisis of human destiny. It may see our rivers, like those of Egypt, turned into blood. It may witness similar loathsome plagues, and pestilence, and fiery hail, and darkness palpable. But may it never behold the dread work of the destroying angel as of old, at the midnight hour, in every dwelling whose lintels were unmarked by the typical blood of the Paschal sacrifice! Avoiding the last dread scene of the great Egyptian drama, may we have, not the Jewish Passover, but the grand American jubilee, when we may hail the South redeemed from the curse of slavery, and forever united with the North, as the one blessed home of universal freedom.

As the South was as earnest as the North in protesting against the landing upon our shores of the first cargo of African slaves, and the continuance of the traffic so long forced upon us under the British flag, and as they all united in excluding the word 'slave' from the Federal Constitution, so will they ultimately coöperate in expunging from our system the institution of slavery.

I shall discuss this question as to the border States under no sectional or party aspect, no influence of passion or prejudice, or any motive but the desire to promote the good of my country. Our national and material interests must be fully considered, as also those great moral principles and intellectual developments which exalt and dignify the character of man. I shall examine the subject inductively and deductively, the facts and the causes.

That a return to the Union with gradual emancipation and colonization by the rebel States would be best for them and for us is certain. But in justice to loyal citizens and communities, and to avoid the danger of foreign intervention by prolonging the contest, it is our duty, after the close of this year, to withdraw the slaves in the rebel States from the culture of the crops used to support their armies, which can only be done by general emancipation in such States persisting then in the rebellion. This is a necessary war measure, designed, like battles or blockades, to suppress the rebellion (alike ruinous to North and South), and which must no longer be permitted to accumulate an immense debt and oppressive taxation, and to exhaust our blood and treasure. The census shows that very few slaves are held by the deluded masses of the South, that the slaveholders are few in number; and full compensation is contemplated by Congress and the President, in all cases of the manumission by us of the slaves of loyal citizens.

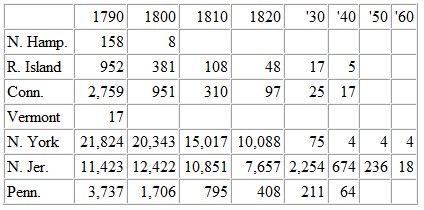

By the census of 1790, all the sixteen States then enumerated held slaves, except Massachusetts (then including Maine, although numbered separately), where the institution was abolished by a judicial construction of their constitution of 1780. The following table, from the census, shows the gradual disappearance of slavery from seven of these States, the remaining eight States still continuing the institution:

Illinois, by her constitution of 1818, continued slavery in the State, but declared that 'children hereafter born shall be free.' An effort was made in Congress to defeat the admission of Illinois, on the ground that its constitution 'did not conform to the ordinance of 1787.' But it was then decided by the House of Representatives (117 to 54) that 'the ordinance did not extend to States.' In the Senate the vote was unanimous. (See Niles's Register, vol. xix. p. 30.) Rhode Island adopted the Pennsylvania system. Connecticut declared free, at the age of 26, all born after the 1st March, 1784. Indiana pursued in its results the course of Illinois. By the census, Illinois had 917 slaves in 1820, 747 in 1830, 331 in 1840; and Indiana had 190 slaves in 1820, 3 in 1830, and 3 in 1840. New York in 1799 continued in bondage the slaves then living, but those born after the date of the law were emancipated at the age of 28; and in New Jersey, the males at 25 and the females at 21. This slow and gradual process in States having so few slaves, should inculcate kinder and more indulgent feelings as to those loyal communities where the slaves are so much more numerous, and the time and mode of action so vital.

The great model act of gradual emancipation, drawn by Benjamin Franklin, the great leader on this question, approved by the Quakers, and adopted by Pennsylvania in 1780, liberated all the descendants of slaves born after that date within the limits of the State. To avoid circumlocution, I shall call those born before the date of emancipating laws the ante nati, and those born after the date of such laws, post nati.

I shall consider first the question of gradual emancipation and colonization in connection with Maryland, and afterward apply the same principles to other States.

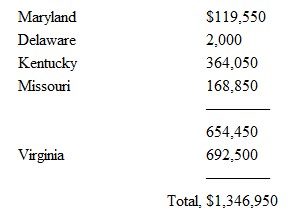

If the Pennsylvania system of liberating immediately only the post nati, so much more liberal than that of most of the free States, were adopted by Maryland, the cost of manumission there would be very small. In the execution of the emancipation act of Congress in this District, infant slaves were valued officially this year by sworn experts at $50 each. Now by the census of 1860, the infant slaves of Maryland, under one year old, surviving on the 1st June, 1860, numbered 2,391, which, at $50 each, would cost $119,550. This would be the actual expense for the first year in Maryland, but decreasing every year, and ceasing altogether in little more than a generation. Now the total number of slaves under one year of age, born in all the slave States, and surviving on the 1st June, 1860, was, by the census, 113,581, which, at $50 each, would cost $5,679,050, for the first year, and decreasing annually as above stated. The post nati numbered in Delaware 40, in Kentucky 7,281, in Missouri 3,377, and in Virginia 13,850, making the first year's cost as follows:

Now then, applying this principle to Maryland, Delaware, Kentucky, and Missouri, the cost, the first year, would be $654,450, and, if we included Virginia, $1,346,950. This sum, we have seen, would decrease every year. According then to the annual tables, and those of expectancies of life (as calculated for me), the sum of fifteen millions of dollars of United States stock, issued now, and bearing interest at the rate of six per cent, per annum, would make all the border States free States, in the same sense in which Pennsylvania and other Northern free States became so; and less than half this sum, if Virginia should not adopt the measure. The case, then, as regards the border States, presents no financial difficulty whatever. If this plan were adopted, the same just and humane course would doubtless be pursued as in the North, by which the emancipated post nati would remain apprentices until they reached twenty-one years of age, under the same regulations, mainly, as were applicable to white children, bound out by the overseers of the poor. Should the border States consent to proceed more rapidly, I have no doubt the Government would cheerfully pay to loyal masters such additional sum as would give freedom to every slave in all the border States, on the 4th of July, 1876, our first centennial anniversary of the Declaration of American Independence. That day, then, already so distinguished in the annals of humanity, would become the great epoch in the history of our race.

And now let us examine the cost of all these measures. If the seceded States, including Virginia, should persist in the rebellion until after the close of this year, the sum to be paid the loyal owners of slaves manumitted under the President's war proclamation would probably reach $100,000,000. The emancipation of the post nati, in the four remaining border States, would cost §7,288,132. The manumission in those States, of all the surviving slaves, on the 4th July, 1876, according to the same tables and estimates, would cost a sum equal to $65,000,000, issued now as United States six per cent. stock, making a total for complete emancipation in all the slave States of $172,288,132. This is a smaller sum than four months' cost of the war, whilst wholly and forever removing the discordant element which produced the rebellion, commencing a new and glorious career of material, moral, and intellectual progress, greatly exalting the character of the nation, invoking the blessing of God, securing the future harmony and perpetuity of the Union, and the ultimate fraternity of man. Never, before, would any nation have made so grand an investment in the gratitude of emancipated millions, the thanks of a world redeemed from bondage, the applause of the present age and of posterity—the exchequer of time and eternity. It would live forever in history, and the recording angel would inscribe it in God's eternal archives. Statesmen, scholars, savans, philosophers, poets, patriots, orators, and divines would proclaim its glory. The new drama of man's political redemption would be witnessed by the audience of the world. Music would chant its praise in every clime, and all peoples would swell the chorus. The painter would give it immortality, and the sculptor monuments more enduring than the pyramids, statues more godlike and sublime than ever crowned Grecian Parthenon, or adorned with Parian marble the temples of Augustan Rome. The press would glow with enthusiasm, and the procession of nations march in the grand ovation, not to national airs, or under national banners, but under the world's new flag, and to the music of the world's new anthem of universal freedom and regenerated man.

The census proves that our progress as a nation has been greatly retarded by slavery. If the North had retained, and the South had abolished slavery, their relative positions would have been reversed. Virginia would have taken the place of New York, Maryland of Massachusetts, Delaware of Rhode Island, Kentucky of Ohio, Missouri of Illinois, and Tennessee of Indiana.

I begin with Maryland, because, in proportion to her area, she has greater natural advantages than any one of the thirty-four States, and, if the comparison with the free States is most unfavorable to her, it will be more so as to any other Southern State, as the census shows that, from 1790 to 1860, and from 1850 to 1860, Maryland increased in population per square mile more rapidly than any other slaveholding State.

Maryland borders for two hundred miles the great free State of Pennsylvania, and Delaware one hundred and thirty miles, whose slaves have decreased from 8,887 in 1790, to 1,798 in 1860, and where slavery now exists in name only. Delaware, like Maryland, is also a loyal State, and would be the last to leave the Union, which it was her glory first to enter under the Constitution of 1787. On the west, Maryland is bounded by Preston county, Virginia, containing in 1860 a free population of 13,312, and 67 slaves only. Western Virginia, bordering Maryland on the south, has voted with great unanimity to become a free State, and all appearances indicate that slavery will disappear from Virginia with the close of this year. Maryland then would be surrounded entirely by non-slaveholding States.

Within the heart of Maryland stands this District, where slavery is now abolished, producing serious losses and embarrassments to the State. The two counties of Prince George and Montgomery, adjoining this District, contained in 1860, 17,790 slaves, being more than one fifth of the slaves of the State. How long can slavery endure, and of what value is it in these counties, where every slave brought or sent to the District is free, and where it is already seriously contended that the language of the Constitution, 'slaves in one State, escaping into another,' cannot apply to this District? With the feeling so intensified already by this rebellion against slavery, it cannot long exist in Maryland. By advancing legislation, and public sentiment, the fugitive slave law is becoming inoperative, and slaves in Maryland are now held by a most precarious tenure. Indeed, unforeseen events, as this terrible rebellion progresses, may sweep slavery from Maryland without compensation or colonization.

But, independent of present or future perils, it is proposed to prove, mainly by the census, that all the material interests of Maryland would be greatly promoted by her prompt acceptance of the offer of Congress. We must consider the area, soil, climate, mines, hydraulic power, location, shore line, bays, sounds, and rivers, and such other causes as affect the advance of wealth and population.

The relative progress of Maryland has been slow indeed. The population of the Union, by the census of 1790, was 3,929,827, of which Maryland, containing then 319,728, constituted a twelfth part (12.29). In 1860, the Union numbered 31,445,080, and Maryland 687,034, constituting a forty-fifth part (45.76). In 1790, the free States numbered 1,968,455, Maryland's population then being equal to one sixth (6.12); but, in 1860, the population of the free States was 18,920,078, Maryland's number then being equal to one twenty-seventh part (27.52). But, if Maryland had increased as rapidly from 1790 to 1860 as the whole Union, her proportion, one twelfth part, would have made her numbers in 1860, 2,620,315; and if her proportional increase had equalled that of the free States, her ratio, one sixth, would have made her population in 1860, 3,153,392. She might not have reached either of these results; but, before closing these articles, it will be proved that, in the absence of slavery, her population, in 1860, would have been at least 1,755,661, or the same per square mile as Massachusetts; and Baltimore, bearing the same ratio to this number as to Maryland's present population, would have contained in 1860, 542,000, instead of 212,000, her present number.

I take the areas from the able report (November 29, 1860) of the Hon. Joseph S. Wilson, then Commissioner of the General Land Office, where they are for the first time accurately given, 'excluding the water surface.' The population is taken from the census, the tables of 1850 and 1860 being compiled with great ability, by the present superintendent, the Hon. J. C. G. Kennedy. I compare first Massachusetts and Maryland, because they are maritime and old States, and both in 1790 had nearly the same population, but, as will be shown hereafter, with vastly superior natural advantages in favor of Maryland.

Area of Maryland, 11,124 square miles; shore line, by tables of United States Coast Survey, viz.: main shore, including bays, sounds, &c., 503 miles, islands 298, rivers to head of tide water 535; total, 1,336 miles.

Area of Massachusetts, 7,800 square miles; shore lines, by tables of United States Coast Survey, viz.: main shore, including bays, sounds, &c., 435 miles, islands 259, rivers to head of tide water 70; total, 764 miles. When we mark the Potomac and its tributaries, the lower Susquehanna, the deep and numerous streams of the Chesapeake, the commercial advantages of Maryland over Massachusetts are vast indeed. Looking at the ocean shore of Maryland, and also at the Chesapeake bay, the largest and finest estuary in the world, indented with numerous sounds and navigable inlets, three fourths of its length for both shores being within Maryland, and compare this deep and tranquil and protected basin, almost one continuous harbor, with the rock-bound coast of Massachusetts, lashed by the stormy Atlantic, the superiority of Maryland is striking.

Mortality in Maryland, by the late census, viz.: deaths from 1st June, 1859, to 31st May, 1860, 7,370 persons. Same time in Massachusetts, 21,303; making the ratio of deaths to the number living in Maryland, one to every 92, and in Massachusetts one to every 57; and the percentage of deaths in Maryland 1.09, and in Massachusetts 1.76. This rate of mortality for Massachusetts is confirmed by the late official report of their Secretary of State to the Legislature.

As to area, then, Maryland exceeds Massachusetts 43 per cent.; as to the shore line, that of Maryland is nearly double that of Massachusetts, having 68 miles more of main shore, bays, and sounds, 38 miles more for islands, and nearly eight times the number of miles for rivers to head of tide water. As to climate, that of Maryland, we have seen, is far the most salubrious. This is a vast advantage, not only in augmented wealth and numbers, from fewer deaths, but also as attracting capital and immigration. This milder and more salubrious climate gives to Maryland longer periods for sowing, working, and harvesting crops, a more genial sun, larger products, and better and longer crop seasons, great advantages for stock, especially in winter, decreased consumption of fuel, a greater period for the use of hydraulic power, and of canals and navigable streams. The area of Maryland fit for profitable culture is more than double that of Massachusetts, the soil much more fertile, its mines of coal and iron, with the fluxes all adjacent, rich and inexhaustible; whereas Massachusetts has no coal, and no valuable mines of iron or fluxes. When we reflect that coal and iron are the great elements of modern progress, and build up mighty empires, this advantage of Maryland over Massachusetts is almost incalculable. The hydraulic power of Maryland also greatly exceeds that of Massachusetts. Such are the vast natural advantages of Maryland over Massachusetts. Now let us observe the results. Population of Maryland in 1790, 319,728; in 1860, 687,034; increase 367,300. Population of Massachusetts in 1790, 378,717; in 1860, 1,231,065—increase 852,348; difference of increase in favor of Massachusetts, 485,048; excess of Massachusetts over Maryland in 1790, 58,989, and in 1860, 544,031. This result is amazing, when we regard the far greater area of Maryland and her other vast natural advantages. The population of Maryland in 1790 was 28 to the square mile (28.74), and in 1860, 61 to the square mile (61.76); whereas Massachusetts had 48 to the square mile in 1790 (48.55), and 157 to the square mile in 1860 (157.82). Thus Massachusetts had only 20 more to the square mile in 1790, and 96 more to the square mile in 1860. But if the areas of Maryland and Massachusetts had been reversed, Massachusetts, with the area of Maryland, and the population of Massachusetts of 1860 to the square mile, would have numbered then 1,755,661, and Maryland, with the area of Massachusetts and the population of Maryland of 1860 to the square mile, would have had then a population of only 481,728 upon that basis, leaving Massachusetts in 1860, 1,273,393 more people than Maryland. Thus is the assertion in a former part of this article now proved, 'that in the absence of slavery, the population of Maryland in 1860 would have then been at least 1,755,661, and Baltimore at least 542,000.' But, in view of the many other natural advantages of Maryland, as shown in this article, viz.: in climate and salubrity, in shore line and navigable rivers, in fertility of soil, and hydraulic power, in a more central location for trade with the whole Union, and especially with the West, and nearer supplies of cotton, and, above all, in coal and iron, it is clear, in the absence of slavery, Maryland must have contained in 1860 a population of at least two millions. By the census of 1790, Massachusetts was the fourth in population of all the States, and Maryland the sixth; but in 1860, Massachusetts was the seventh, and Maryland the nineteenth; and if each of the thirty-four States increases in the same ratio from 1860 to 1870, as from 1850 to 1860, Maryland will be only the twenty-fifth State.

These facts all conclusively attest the terrible effects of slavery on Maryland, and this is only one of the dreadful sacrifices she has made in retaining the institution. As to wealth, power, and intellectual development, the loss cannot be overstated.

Nor can manufactures account for the difference, as shown by the still greater increase of the agricultural North-West. Besides, Maryland (omitting slavery) had far greater natural advantages for manufactures than Massachusetts. She had a more fertile soil, thus furnishing cheaper food to the working classes, a larger and more accessible coast, and nearly eight times the length of navigable rivers, greater hydraulic power, vast superiority in mines of coal and iron, a far more salubrious climate, cotton, the great staple of modern industry, much nearer to Maryland, her location far more central for trade with the whole Union, and Baltimore, her chief city, nearer than Boston to the great West, viz,: to the Ohio at Pittsburg and Cincinnati, the Mississippi at St. Louis, and the lakes at Cleveland, Toledo, and Chicago, by several hundred miles. Indeed, but for slavery, Maryland must have been a far greater manufacturing as well as commercial State than Massachusetts—and as to agriculture, there could be no comparison.

But Massachusetts did not become a manufacturing State until after the tariff of 1824. That measure, as well as the whole protective policy, Massachusetts earnestly opposed in 1820 and 1824, and Daniel Webster, as her representative, denounced it as unconstitutional. From 1790 to 1820 Massachusetts was commercial, not manufacturing, and yet, from 1790 to 1820, Massachusetts increased in numbers 144,442, and Maryland in the same time only 87,622. Yet, from 1790 to 1820, Massachusetts, the most commercial State, was far more injured by the embargo and the late war with England than any other State.

It is clear, then, that the accusation of the secession leaders that the North was built up at the expense of the South, by the tariff, can have no application to the progress of Massachusetts and Maryland, because the advance of the former over the latter preceded by more than thirty years the adoption of the protective policy, and a comparison of the relative advance of the free and slave States, during the same period, exhibits the same results.