полная версия

полная версияLippincott's Magazine of Popular Literature and Science, Vol. 22, November, 1878

The colony in the glass jar seemed perfectly contented, not trying to make their escape at all. The earth was originally a little more than two inches in depth, but by the first of February these wonderful architects had reared their domicile to the height of six inches. They raised tier upon tier of chambers in so substantial a manner that they never fell in. One of the store-rooms in which they deposited the seeds I gave them was at the bottom of the jar, and the seeds were stored against the glass with no intervening earth between: it contained about a teaspoonful of millet. I gave this chamber the right degree of heat and moisture to sprout the seed by pouring a little water down the side of the jar until it penetrated the chamber, and then setting it near the fire. The ants soon appreciated the condition of this store-room, and many congregated there and seemed to be enjoying a feast. The next day the seeds were all brought to the surface and deposited in a little heap on one side of the jar, where many of them grew, making a pretty little green forest, which the ants soon cut down and destroyed. This chamber remained empty for three or four days, and was then again refilled with fresh millet and apple and croton seeds.

I kept a small shell, which held about a tablespoonful of water, standing in the jar for the ants to drink from. For more than a month the water was allowed to remain clear, the ants often coming to the edge to drink; but one day one was walking on the edge of the shell, and carrying an apple-seed, when she lost her footing and rolled into the water. She floundered about for a few moments, still holding on to the seed: at last she let it drop and crawled out. As soon as she had divested herself of the surplus water, she consulted several of her companions, and they immediately went to work and filled up the shell, first throwing in four or five apple-seeds, and then filling in with earth; and ever after, as often as I cleared out the shell and put in fresh water, it would be filled with earth, sticks and seeds; and they now served all sweet liquids which I gave them in the same way, sipping the syrup from the moistened earth.

Like other ants, they are very fastidious about removing their dead companions. I buried one about half an inch beneath the soil. Very soon several congregated about the spot and commenced digging with their fore feet, after the manner of digger-wasps, throwing the earth backward. They soon unearthed and pulled the body out, when one seized and tried to remove it, climbing up the side of the jar, and falling back until I relieved her of the burden.

From time to time I add new recruits of soldiers and workers to the jar. This always causes a little confusion for a few moments: there is a quick challenging with antennæ, but no fighting, and soon all are working harmoniously together. I found three half-drowned, chilled ants near the mound from which most of the inhabitants of the jar were taken. One was not only wet and chilled, but also covered with sand. These I put on a small leaf and placed in the centre of the jar. The genial warmth soon revived them. Many of their old companions clustered around them, and there seemed to be considerable consultation. The two wet ants were soon made welcome, and, leaving the leaf, were conducted by their comrades—from whom they had been separated for more than two months—to the rooms below. But the one covered with sand—a major—did not meet with so kindly a reception. She still remained on the leaf trying to cleanse herself. All the ants had left her save one, who was determined to quarrel with her. I removed this one, and now another came up, bit at her and annoyed her until I removed this one also. Then some half dozen congregated about the leaf, touching her with their antennæ and walking round her. By this time she was nearly free from the sand, and was looking quite bright, strutting about the leaf in a threatening attitude, with her mandibles wide apart. She was not attacked by these last inspectors, though still looked upon a little suspiciously. I then returned the two quarrelsome ants: they immediately walked up to their unfortunate comrade, and now seemed to be satisfied that she was a respectable ant, and admitted her into the community with no further challenging.

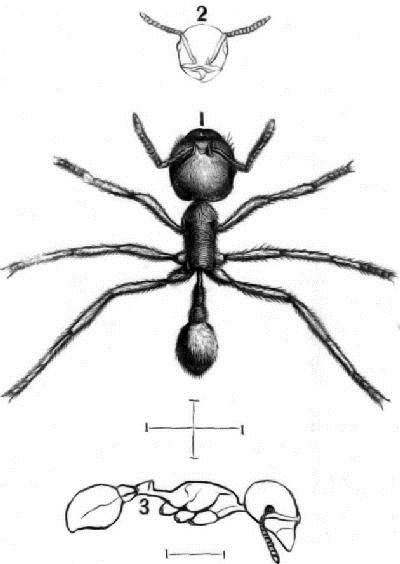

1. WORKER MAJOR.

2. OUTLINE OF HEAD OF WORKER MAJOR.

3. OUTLINE OF BODY OF WORKER MINOR.

I found a nest of large carpenter-ants (Camponotus atriceps, var. esuriens, Smith) which had made their home in fallen timber. Upon examining their work, it was evident they must have strong tools to work with, for the numerous rooms and chambers of their domicile were often made in firm, hard wood. They are the largest, most vicious species I have ever seen. I introduced one of these terrible creatures into the jar among the quiet, peaceful occupants. A large worker major immediately closed with her: it was so quickly done that I could not tell which was the attacking party. They rolled about a few moments in a close embrace, till they rolled out of sight through the wide entrance to one of the rooms below. There was considerable excitement and increased activity among the workers, who were constantly bringing to the surface bits of earth which the struggling warriors had loosened. In about an hour the head of the carpenter was brought out, divested of every member: both the antennæ and palpi were gone, cut close to the head. A little later the abdomen was brought out, and still later the thorax with not an entire leg left.

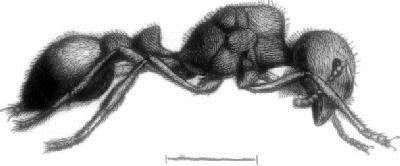

QUEEN: SIDE-VIEW, SHOWING PECULIAR CONFORMATION OF THE THORAX.

Several times during the months of January and February I introduced into the jar a number of half-grown larvæ of the harvester. Without any hesitation they were quickly carried to the rooms below by the workers minor. On the 4th of February I found a large number of the larvæ of the carpenter-ant (Camponotus meleus, Say). They were very small, and closely packed together in a chamber cut out of hard wood, two inches in length and an inch and a quarter in diameter, nearly circular. It was packed full of larvæ and eggs, the larvæ apparently just hatched. I detached a small mass, all stuck together, and placed them in the jar with the harvesters. The workers minor immediately surrounded the mass, touching it with their antennæ, and then retreated backward, passing their fore legs over the head and antennæ, as if the larvæ were obnoxious to them. Great commotion ensued, followed by an apparent consultation lasting a few moments; but soon the usual quietness reigned, and most of the ants left the helpless larvæ and returned to their mining and to the storing away of seeds or feeding their own young. But two or three had not entirely deserted the young carpenters. Again and again they touched them, and then retreated, cleansing the antennæ as they moved backward. At last one seized the mass and held it in her mandibles, standing nearly in an upright position. Several workers now surrounded her, picked the larvæ off, one by one, and carried them below, until all were separated and disposed of.

But by far the most satisfactory way of studying the ants is in their native haunts on the barrens, where I had ten nests under observation. One of these was so situated that it received the direct rays of the sun all day, and was protected from north and east winds by dense, low shrubbery. On sunny days, even with a cool wind from the north, when taking my seat in this sheltered spot, I would soon become uncomfortably warm. This hill was always active whenever I visited it, while in other localities the ants would often be all housed. Around this active nest I stuck stems of millet eighteen inches high, surmounted by the close-packed heads. The ants climbed the stems, loosened and secured the seeds, and stored them within the nest. They worked vigorously, sometimes twenty or more on one head pulling away at the seeds. In my artificial formicary they did not mount the stems, even when the heads were not more than three or four inches from the ground, but seeds that I scattered in the jar were always taken below.

I threw down a handful of apple-seeds near the entrance of the active hill on the barrens. This immediately attracted a large number of excited ants. They rushed to the seeds in a warlike attitude, and began carrying them off, depositing them two or three feet away. But as soon as the excitement caused by the sudden pouring down of the seeds had subsided, they seemed to comprehend that they had been throwing away good seeds; and now, changing their tactics, not only carried the remainder into the nest, but finally brought back and stored all those that had been thrown away.

On excavating the nests we found granaries of seed scattered irregularly throughout to the depth of twenty-two inches below the surface of the ground: some were near the surface, and a few sprouted seeds were scattered about in the mound. The mound is usually not more than four to six inches above the level of the ground.

The great majority of nests that I have found are in the low pine barrens—so low that on reaching the depth of two feet the water runs into the cavity like a spring, and stands above some of the granaries. Notwithstanding this wet locality, I found no sprouted seeds in the deeper store-rooms, but only in the warmer mound. On sunny days the larvæ are brought up into the mound and deposited in chambers near the surface, where they receive the benefit of the sun's rays. On cool, cloudy days and in the early morning I found no larvæ near the surface. If the ants are intelligent enough to treat the larvæ in this way, why should they not store seeds where they will not sprout? And when they need to sprout them in order to obtain the sugar they contain, it would take no more wisdom to treat the seed as they do the larvæ—bringing them near the surface to obtain the right degree of heat for the required result.

The little workers seem very determined not to allow any green thing to grow on their mounds. Cassia and croton and many other plants start to grow from seeds which the ants have dropped, but they are always cut down and destroyed if too near the mound, though allowed to grow at a little distance; so that a botanist would be astonished at the great variety of plants within a small area if not aware of the source from which they came. I sometimes found small shrubs of Kalmia hirsuta and Hypericums entirely dead on the mounds, the roots completely girdled in many places. It is very amusing to watch them in their efforts to destroy grass and other plants. Their determined persistence is remarkable: they cut off the tender blades and throw them away. But they do not stop here: the roots must be exterminated; so several dig around the plant, throwing the earth backward, and after making it bare they cut and girdle the roots until the plant is killed.

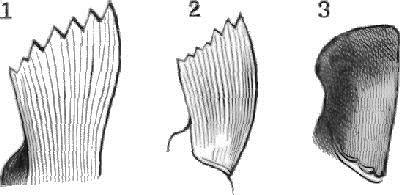

1. With well-formed teeth.

2. Partially developed.

3. Entirely obsolete.

MANDIBLES OF THE HARVESTING-ANT.

Early in March the ants in the jar seemed to have completed their domicile. At first, several chambers were visible through the glass, and the galleries leading to them, but gradually the light was all shut out by placing little particles of earth against the glass, thus depriving me of the opportunity of watching their movements within the nest. So I now took the jar to the barrens, and set it by the side of a nest which was about a mile distant from where most of the ants were obtained. Here I carefully broke it, and took the thin shell of glass from around the nest, which did not fall, but stood six inches in height and eighteen inches in circumference. With a large knife I removed a thin layer of earth, which revealed three admirable chambers with galleries leading from one to the other. Immediately below there were five chambers well filled with ants, and below these other chambers were scattered irregularly throughout, with only thin partitions between.

At various times I had given the ants moistened sugar on the thick curved leaves of the live-oak, and several of these had been covered while the ants were making their excavations. Two of the leaves were three inches below the surface, and the ants had utilized them by making the inner curved surface answer for the floor and sides of fine chambers; and here a large number of ants, both soldiers and workers, were crowded together. In other chambers I found the larvæ, which were greatly increased in size since I had placed them in the jar; and the larvæ of the carpenter-ant were being reared, as I found some smaller than any I had introduced belonging to the harvester.

Very soon a great crowd of excited ants came from the hill near which I had broken the jar, and began to transport the larvæ, and also the mature ants, to their own dominions. There was no fighting: the ants from the jar submitted to being carried, not offering the least resistance. A small worker would often take hold of a large soldier, sometimes pushing, sometimes dragging, her through the sand, and she would be as quiet as if dead or dying; but if we touch the little worker she leaves her burden and rushes about to see what the interference means; and now the soldier straightens up, as bright and lively as the rest, and after passing her fore legs over her head and body, goes of her own accord into the new nest, meeting with no opposition. Some of the ants would coil up and allow themselves to be carried easily. Others were led along by an antenna or a leg, in either case manifesting no resistance. For three hours I watched the proceeding, and could see no fighting. It looked precisely as if the inhabitants of the jar realized their helpless condition, and gladly submitted to be taken prisoners or to become partners with this new firm.

I left them, and after the lapse of two hours again visited the spot. The seeds that had been in the jar were now being transferred to the other nest, and two new entrances at the base of the mound were being made. And now every little while an ant would be ejected from the nest. One worker would bring another out and lay her down, often not more than three inches away from the door, but, so far as I could see, she was in no wise injured. Her first movement was to make herself presentable by passing her fore legs over her head and body: as soon as this was completed she returned within the nest. But there was one large soldier which the whole community seemed combined against. She was led or dragged away from the entrance of the nest eight times, and each time left at the base of the mound among the rubbish. Sometimes she was led or carried by one alone, sometimes two or three would conduct her, and then leave her, when she would at once proceed to make her toilet; which completed, she would again return to the door of the nest, when she would be again conducted away, offering no resistance. I now picked her up, which made her very fierce. She seized my glove with her powerful mandibles, and held on with a persistency equal to the most vicious species, at the same time trying to use her sting. As soon as I could free her from the glove I secured her, and on reaching home placed her under the microscope, and found she was not injured and had strong teeth in her mandibles.

On the next day I returned her to the nest, and again she was met by the indignant police at the door and conducted away. With her strong mandibles she could have crushed any number of her small assailants, but in no instance did she show the least disposition to rebel against the indignities to which she was subjected. She was often dragged away with her back on the ground and her legs coiled up, apparently helpless. If all the soldiers had been treated in this way, it would not have been so remarkable, but so far as I could see the rest were allowed to remain, going in and out of the nest as if taking a survey of their new surroundings.

For five months I had these ants under almost constant observation, and yet I was unable to make out the true position of the soldiers in the colony. They stay mostly within the nest. On the warmest days a few will come out and walk leisurely around the mound. They are not scattered irregularly through the nest, but seem to be housed together in large chambers. In one of these chambers I found a wingless queen in their midst. It seemed very fitting for a queen to be surrounded by Amazon soldiers; but, alas! they seemed more like maids of honor than soldiers, for they forsook the royal lady without making an effort to defend her. Not so, however, with the little workers: they rallied around her, ready to guard her with their lives, and no doubt would have succeeded had it been any ordinary foe.

This phenomenon—the soldiers and queens with smooth mandibles—is very puzzling, and has excited much interest among naturalists both in this country and in Europe. I sent specimens to Mr. Charles Darwin, which he forwarded to Mr. Frederick Smith of the British Museum (who, Mr. Darwin informs me, is the highest authority in Europe on ants and other Hymenoptera). Mr. Smith says: "Your observations on the structural differences in the mandibles of this ant are quite new to me." I also sent specimens to the eminent naturalist Dr. Auguste Forel of Munich, who, like Mr. Smith, had never observed this feature of the mandibles in any ant; but he has a theory to account for it—that the smooth mandibles have been worn down by labor. If this theory is true, how can we account for the fact that other ants do not wear down their teeth? The chitinous covering of this harvesting-ant is firm and hard. The stage forceps of my microscope closes with a spring, and in studying this ant I have put thousands of individuals to the test, holding them in the forceps to examine their mandibles, and in no instance do I recollect seeing one injured, while many other species are easily injured by the forceps. Among these are the two large species of carpenter-ant before mentioned, which work in stumps or fallen timber. These ants all have well-developed teeth, and the shell-like covering enveloping the body is much thinner than that of the harvesting-ant.

If it be urged that hard wood will not wear down the teeth like mining in the sandy soil, I can bring forward another member of this family (Camponotus socius, Roger), which lives in the ground, and whose mining and tunnelling are on a much more extensive scale than those of the harvesting-ant. The formicary of this Camponotus often extends over several square rods, with large entrances at various points, all connected by underground galleries, requiring a great amount of labor to construct them; while each colony of the harvesting-ant has a close, compact nest or formicary, requiring much less work to construct it. The worker major of Camponotus socius is very large—larger than the soldier of the harvesting-ant. The formicaries of the two species are often in close contact, so that the nature of the soil is precisely the same. I have examined thousands of Camponotus socius, and in no instance have I found the teeth worn down.

There is still another difficulty in the way of Dr. Forel's theory. Careful observations have revealed the fact that all the harvesting-ants that engage in work of any kind are armed with teeth. I took thirty soldiers with smooth mandibles, put them in a glass jar with every facility for making a nest, but they refused to work, scorned all my offers of food, and remained huddled together for three days. I then introduced several workers minor, and they immediately commenced tunnelling the earth and making chambers, into which the lazy soldiers crawled, meeting with no opposition from these industrious little creatures. My experiments did not stop here. I now took about a hundred specimens—soldiers and a few workers major, the last with partially-developed teeth—and placed them in a jar. Some of these made feeble attempts to construct a nest, but they did not store away seeds, and larvæ which I put in the jar they carried about as if not knowing what to do with them.

There is every appearance of an aristocracy among these humble creatures. The minors are the servants who do the work, while the queens and soldiers (especially the soldiers, which more nearly approach the queen in shape of head and mandibles) seem to live a life of comparative ease, and have their food brought to them by the minors. This may be the reason of the non-development of the teeth among the aristocracy. But how the same parent can produce such differing offspring—some born to a life of ease, with obsolete teeth, and others with well-developed teeth to do the work—is one of the mysteries in Nature. The only way to settle the point with regard to the mandibles beyond dispute is to find the pupæ of very young queens and soldiers, which I was unable to do during my stay in Florida. All the young were in the larval state.

Mary Treat.DOCTEUR ALPHÈGE

"MARCELLINE! Marcelline! viens m'aider: je souffre!"

The voice was thin and querulous, but painfully weak, and the stalwart, broad-shouldered negress to whom the cry was addressed had an anxious, startled look on her usually stolid face as she turned away from the open door and went into the sick room.

"My poor mistress," she said tenderly in French, raising in her arms as she spoke the attenuated form of the suffering woman before her and rearranging her pillows, "you feel very bad to-day: I knew you did just now when you were asleep and I heard you groaning. I wish—bon Dieu!—I wish I could do something for you."

The invalid made no reply for a minute, but gazed piteously up into the other's face. She was a woman of about fifty, who even in the last stages of emaciation and weakness showed traces of wonderful beauty. The sharp, drawn features were as clear and fine as those of a model, and even now the sweetness and brilliancy of her dark-blue eyes were little diminished. But pain of some kind and utter prostration held her in their grip, and she made several attempts to speak before she said, in a hoarse whisper, "Thou canst help me, child. Food, Marcelline! food, for the love of God!"

The negress started, knit her brows and murmured anxiously, "Oh, my dear mistress, anything but that! Think what would happen to me and my children if—if—"—she seemed almost afraid even to whisper the name, but sank her voice to the lowest tone as she continued—"if Mons. Alphège were to find me out. Attends!" she added aloud and coaxingly: "it will soon be time for your supper now: when the bell rings you are to have some milk, and the sun is almost down."

The sick woman groaned and lay quite still, but when, in a few minutes, a clanging plantation-bell rang the joyful announcement that the day's work was over, she grasped the milk which Marcelline brought her like one famished, and drained it without breathing. It was a short draught, after all, for the cup was only half full, but Marcelline turned away with a shiver from the imploring eyes and outstretched hands, which asked her to replenish it, and, as though unable to endure the sight of suffering which she could not alleviate, went out upon the open gallery and sat down on the steps.

The room was on the ground floor, and the house was an old-fashioned creole dwelling, long and low, with many doors and innumerable little staircases—everything in disorder and out of repair, and weeds and grass growing up to the threshold. There was a well-stocked and carefully-tended vegetable garden not a hundred yards off: the poultry-yards, dove-cotes and smoke-houses were as full as they could hold, and over yonder, just behind the tall picket fence, were corn-cribs bursting with corn and hay-lofts choked with hay. Fifty or sixty negro hovels, irregularly grouped together down by the bayou-side, and indistinctly seen in the fading twilight, contained about three hundred slaves, who, having trooped in from the field at the sound of the bell, were now eating pork and hominy as fast as they could swallow. But no one would have guessed that all this abundance was at hand, or that this was the homestead of one of the richest creole families in the State. Yet it was so. Old Madame Levassour—or Madame Hypolite, as she was invariably called—was not only the widow of a wealthy planter, but had been herself a great heiress, perhaps the greatest in the whole South, at the time of her marriage. The property had gone on appreciating, as slave property did in old times, and now that she was lying at the point of death, her two daughters, who had married brothers, and, like all true creoles, still lived at home with their mother, would soon be enormously rich. They were well off already by inheritance from their father, and each owned a valuable plantation and many slaves; but these were nothing compared to the possessions of their mother, who was an excellent business-woman, full of energy, prudence and moderation, and never weak or capricious, especially where the interests of others were concerned. She had always been a kind and indulgent mistress to her slaves, who loved her in return with passionate fidelity, and many were the sighs and tears their approaching change of owners produced among them. Her sons-in-law were educated men, of good birth and moderate fortune; but negroes are the best judges of character in the world, and there was not a trait or feeling concealed under the quiet, nonchalant exterior of Mons. Volmont Cherbuliez which they did not thoroughly understand. About his brother Alphège, who was a physician, there was more diversity of opinion. That he also was bad, cruel, dissipated, profoundly deceitful, there was no doubt in the minds of his future chattels, but what precise form his idiosyncrasies would take they felt to be uncertain, and gazed with terror—all the more acute for being somewhat vague—at his cold, impassive face. In the mean time, nothing could be more irreproachable than the demeanor of the two brothers. Dr. Alphège was known to be a man of great skill, a graduate of the medical schools of Paris and always interested in the practice of his profession. He devoted himself to his mother-in-law now with unfailing assiduity, and when her disease—which he pronounced to be a dangerous gastric affection—baffled his utmost efforts, he sent for advice and assistance even to New Orleans; which, thirty years ago in South-western Louisiana, was quite an enterprise. His fellow-physicians agreed with him in his management of the case, and the daughters and friends of Madame Hypolite, though deeply grieved by her illness, felt that nothing more could be done. As is usual in diseases of the stomach, her suffering was very great, and the most rigid care had to be exercised in the choice and administration of nourishment. On her food, said Dr. Alphège, he depended for the only hope of a cure: consequently, the rules which he laid down must be, and were, enforced in the most rigid manner. The penalty of transgressing his orders was always severe, but now the fiat went forth that any one of the nurses or attendants upon Madame Hypolite who should depart from his carefully-explained orders in the minutest particular should receive a punishment such as had never been administered in that household before.