полная версия

полная версияLippincott's Magazine of Popular Literature and Science, Vol. 22, November, 1878

"I return the money," Percival wrote, "which you say was so useful to you. I know that what you have sent me is not yours, but your wife's, and I cannot conscientiously say that I think Mrs. Herbert Lisle is indebted to me in any way.

"I have not delivered your message to your sister. I have no wish to insult her in her trouble, and I know she would feel such persuasion a cruel insult, as indeed I think it would be."

Judith at the same time was writing:

"From this time our paths must lie apart. I will never touch a penny of your wife's money. Do not dare to offer me a share of it again. It seems to me that all the shame and sorrow is mine, and you have only the prosperity. Not for the whole world would I change burdens with you.

"Miss Crawford is going to give up her school at once. She will not see or speak to me, for she suspects me of having been your accomplice. And I cannot help blaming myself that I trusted you so foolishly. But I could not have believed that you would have been false to her—our one friend, our mother's friend. Is it possible that you do not see that every one under her roof should have been sacred to you? But what is the use of saying anything now?

"I don't know, after this, how to appeal to you, and I don't want any promises; but if you feel any regret for the pain you have caused, and if you really wish to do anything for me, I entreat you to be good to Emmeline. It is the only favor I will ever ask of you. She is young and weak, poor girl! and she has trusted you utterly. In God's name, do not repay her trust as you have repaid Miss Crawford's and mine!"

Bertie's incredulous amazement was visible in every line of his answer to Percival:

"Are you both cracked—you and Judith—or am I dreaming? I have read your letters a score of times, and I think I understand them less than I did. Here are sweet bells jangled out of tune with a vengeance, and Heaven only knows what all the row is about: I don't.

"Do you suppose a man never made a runaway match before? And how could I do otherwise than as I did? Was I to stop and consult all the old women in the parish about it—ask Miss Crawford's blessing, and get my sister to look out my train for me and pack my portmanteau? Can't you see that I was obliged to deceive you a little?

"And what is amiss with the marriage itself? It is true that just now Emmeline has the money and I have none, but do you suppose I am going to remain in obscurity all my life? A few years hence you shall own that it was not at all a bad match for her. Old Nash is nobody, though he is clever enough in his own way. His father was a tailor, and made a good lot of money so. By the way, he is certainly coming round (Mr. Nash, I mean, not my grandfather-in-law the tailor: he is dead), and if he doesn't object, why should anybody else?

"If I have done Miss Crawford any harm, I'm very sorry of course. Can't I help her in some way?"

The reply to Judith's letter came in a feeble, girlish handwriting. It began: "Herbert tells me you are angry with him because he deceived you about our marriage," and it ended, "Your affectionate sister, Emmeline Lisle." The writer was evidently in the seventh heaven of bliss. Her letter was an attempt at persuading Judith, but it was sprinkled all over with fond allusions to Bertie—"My dear, dear husband," "my own dearest," "darlingest Herbert," "my own love;" and in one place there was an unnecessary little parenthesis: "He is such a dear, you know!" It was silly enough to be maddening, but it was wonderfully happy, with the writer's adoration of Bertie and her serene certainty that Bertie adored her. Clearly, no shadow of doubt had crossed Emmeline's mind. There was not such another man in all the world as Herbert Lisle, and she was his ideal woman. Every other girl must envy her the prize she had won. Even his sister was jealous and angry when she found that she held only the second place in his affections. Emmeline, elated by her proud position, reasoned sweetly with the unreasonable Judith, who read the foolish scribble with mingled irritation, laughter, contempt, and almost tears. At the end were three lines in another hand: "Judith, you must let me send you some money. If you don't understand why yet, you will soon. You really must."

"Does he think I can't get a situation without his help?" Judith wondered. She smiled, for she had found one. Mrs. Barton had come to her assistance—Mrs. Barton, whose stupid little daughter Judith was still patiently teaching. She understood the girl's wish to remain at Brenthill: she believed in her and sympathized with her, and exerted herself in her behalf. She brought her the offer of a situation in a school for little boys, where she would live in the house and have a small salary. "It won't be like Miss Crawford's, you know," the good lady said.

"It will do, whatever it is," Judith answered.

"It is a school of quite a different class. Miss Macgregor is a woman who drives hard bargains. She will overwork you, I'm afraid: I only hope she won't underfeed you. You will certainly be underpaid. She takes advantage of the cause of your leaving Standon Square, and of the fact that you can't ask Miss Crawford for testimonials. She is delighted at the idea of getting a really good teacher for next to nothing."

"Still, it is in Brenthill," said Judith, "and that is the great thing. Thank you very much, Mrs. Barton. I will take it."

"She will reopen school in about ten days."

"That will suit me very well, won't it? I must pack up here, and settle everything." And Judith cast a desolate glance round the room where she had come with such happy hopes to begin a new life with Bertie.

Mrs. Barton's eyes were fixed on her. "I am half inclined now to wish I hadn't said anything about Miss Macgregor at all," she remarked.

"Why? If you only knew how grateful I am!"

"That's just it. Grateful! And that schoolmistress will work you to death: I know she will."

"She must take a little time about it," said the girl with a smile. "Perhaps before she has quite finished I may hear of something else. What I want is something to enable me to stay at Brenthill, and this will answer the purpose."

Mrs. Barton stood up to go. "I've made one stipulation," she said. "Miss Macgregor will let you come to us every Wednesday afternoon to give Janie her lesson."

"Oh, how good you are!" Judith exclaimed. "I thought all that must be over."

"I wish I could have you altogether," Mrs. Barton said. "It would be charming for Janie, and for me too. But, unfortunately, that can't be." She had her hand on the handle of the half-open door. As she spoke there was a quick step on the stairs, and Percival Thorne went by. A slanting light from the window in the passage fell on his sombre, olive-tinted face with a curiously picturesque effect. An artist might have painted him, emerging thus from the dusky shadows. He carried himself with a defiant pride—was he not Judith's friend and champion?—and bowed, with a glance that was at once eager and earnest, when he caught sight of the young girl behind her friend's substantial figure. His strongly-marked courtesy was so evidently natural that it could not strike any one as an exaggeration of ordinary manners, but rather as the perfection of some other manners, no matter whether those of a nation or a time, or only his own. Mrs. Barton was startled and interested by the sudden apparition. The good lady was romantic in her tastes, and this was like a glimpse of a living novel. "Who was that?" she asked hurriedly.

"Mr. Thorne. He lodges here," said Judith.

"A friend of your brother's?"

"He was very good to my brother."

"Ah!" said Mrs. Barton. "My dear, he is very handsome."

Judith smiled.

"He is!" exclaimed her friend. "Don't say he isn't, for I sha'n't believe you mean it. He is very handsome—like a Spaniard, like a cavalier, like some one in a tragedy. Now, isn't he?"

Mrs. Barton's romantic feelings found no outlet in her daily round of household duties. Mr. Barton was good, but commonplace; so was Janie; and Mrs. Barton was quite conscious that there was nothing poetical or striking in her own appearance. But Miss Lisle, with her "great, grave griefful air," was fit to take a leading part in poem or drama, and here was a man worthy to play hero passing her on the staircase of a dingy lodging-house! Mrs. Barton built up a romance in a moment, and was quite impatient to bid Judith farewell, that she might work out the details as she walked along the street.

The unconscious hero of her romance was divided between pleasure and regret when he heard of the treaty concluded with Miss Macgregor. It was much that Judith could remain at Brenthill, but one day, on his way to dinner, he went and looked at the outside of the house which was to be her home, and its aspect did not please him. It stood in a gloomy street: it was prim, straight, narrow, and altogether hideous. A tiny bit of arid garden in front gave it a prudish air of withdrawing from the life and traffic of the thoroughfare. The door opened as Percival looked, and a woman came out, frigid, thin-lipped and sandy-haired. She paused on the step and gave an order to the servant: evidently she was Miss Macgregor. Percival's heart died within him. "That harpy!" he said under his breath. The door closed behind her, and there was a prison-like sound of making fast within. The young man turned and walked away, oppressed by a sense of gray dreariness. "Will she be able to breathe in that jail?" he wondered to himself. "Bellevue street is a miserable hole, but at least one is free there." He prolonged his walk a little, and went through Standon Square. It was bright and pleasant in the spring sunshine, and the trees in the garden had little leaves on every twig. A man was painting the railings of Montague House, and another was putting a brass plate on the door. There was a new name on it: Miss Crawford's reign was over for ever.

Percival counted the days that still remained before Judith's bondage would begin and Bellevue street be desolate as of old. Yet, though he prized every hour, they were miserable days. Lydia Bryant haunted him—not with her former airs and graces, but with malicious hints in her speech and little traps set for Miss Lisle and himself. She would gladly have found an occasion for slander, and Percival read her hate of Judith in the cunning eyes which watched them both. He felt that he had already been unwary, and his blood ran cold as he thought of possible gossip, and the manner in which Lydia's insinuations would be made. Precious as those few days were, he longed for the end. He thought more than once of leaving Bellevue street, but such a flight was impossible. He was chained there by want of money. He could not pay his debt to Mrs. Bryant for weeks, and he could not leave while it was unpaid. Day after day he withdrew himself more, and grew almost cold in his reserve, hoping to escape from Lydia. One morning, as they passed on the stairs, he looked back and caught a glance from Judith never intended to meet his eye—a sad and wondering glance—which made his heart ache, even while filling it with the certainty that he was needed. He answered only with another glance. It seemed to him to convey nothing of what he felt, but nevertheless it woke a light in the girl's eyes. Moved by a quick impulse, Percival looked up, and following his example, Judith lifted her head and saw Miss Bryant leaning over the banisters and watching them with a curiosity which changed to an unpleasant smile when she found herself observed. It was a revelation to Judith. She fled into her room, flushing hotly with indignation against Lydia for her spitefully suggestive watchfulness; with shame for herself that Percival's sense of her danger should have been keener than her own; and with generous pride and confidence in him. Thus to have been guarded might have been an intolerable humiliation, but Judith found some sweetness even in the sting. It was something new to her to be cared for and shielded; and while she resolved to be more careful in future, her dominant feeling was of disgust at the curiosity which could so misunderstand the truest and purest of friendships. "He understands me, at any rate," said poor Judith to herself, painfully conscious of her glowing cheeks. "He understands me: he will not think ill of me, but he shall never have to fear for me again." It might be questioned whether Percival did altogether understand her. If he did, he was more enlightened than Judith herself.

After that day she shrank from Percival, and they hardly saw each other till she left. She knew his hours of going and coming, and was careful to remain in her room, though it might be that the knowledge drew her to the window that looked into Bellevue street. As for Percival, though he never sought her, it seemed to him that his sense of hearing was quickened. Judith's footstep on the stairs was always distinct to him, and the tone of her voice if she spoke to Miss Bryant or Emma was noted and remembered. It is true that this strained anxiety sometimes made him an involuntary listener to gossip or household arrangements in which Miss Lisle took no active part. One day there was a hurried conversation just outside his door.

"Did you give it to her?" said Lydia's voice.

Emma replied, "Yes'm."

"Open? Just as it came? Just as I gave it to you?"

Emma again replied, "Yes'm."

"Did she look surprised?"

"She gave a little jump, miss," said Emma deliberately, as if weighing her words, "and she looked at it back and front."

"Well, what then? Go on."

"Oh! then she laid it down and said it was quite right, and she'd see about it."

Lydia laughed. "I think there'll be some more—" she said. Percival threw the tongs into the fender, and the dialogue came to an abrupt termination. "She" who gave a little jump was Miss Lisle, of course. But there would be some more—What? The young man revolved the matter gloomily in his mind as he paced to and fro within the narrow limits of his room. A natural impulse had caused him to interrupt Lydia's triumphant speech, which he knew was not intended for his ears, but her laugh rang in the air and mocked him. What was the torture that she had devised and whose effects she so curiously analyzed? There would be more—What?

He thought of it that night, he thought of it the next morning, and still he could not solve the mystery. But as he came from the office in the middle of the day he passed his bootmaker's, and the worthy man, who was holding the door open for a customer to go out, stopped him with an apology. Percival's heart beat fast: never before had he stood face to face with a tradesman and felt that he could not pay him what he owed. His bill had not yet been sent in, and the man had never shown any inclination to hurry him, but he was evidently going to ask for his money now. Percival controlled his face with an effort, prepared for the humiliating confession of his poverty, and found that Mr. Robinson—with profuse excuses for the trouble he was giving—was begging to be told Mr. Lisle's address.

"Mr. Lisle's address?" Thorne repeated the words, but as he did so the matter suddenly became clear to him, and he went on easily: "Oh, I ought to have told you that Mr. Lisle's account was to be sent to me. If you have it there, I'll take it."

Mr. Robinson fetched it with more apologies. He was impressed by the lofty carelessness with which the young man thrust the paper into his pocket, and as Thorne went down the street the little bootmaker looked after him with considerable admiration: "Any one can see he's quite the gentleman, and so was the other. This one'll make his way too, see if he doesn't!" Mr. Robinson imparted these opinions to Mrs. Robinson over their dinner, and was informed in return that he wasn't a prophet, so he needn't think it, and the young men who gave themselves airs and wore smart clothes weren't the ones to get on in the world; and Mrs. Robinson had no patience with such nonsense.

Meanwhile, Percival had gone home with his riddle answered. More—What? More unsuspected debts, more bills of Bertie's to be sent in to the poor girl who had been so happy in the thought that, although their income was small, at least they owed nothing. Percival's heart ached as he pictured Judith's start of surprise when Emma carried in the open paper, her brave smile, her hurried assurance that it was all right, and Lydia laughing outside at the thought of more to come. "She'll pay them all," said Percival to himself. "She won't take a farthing of that girl's money. She'll die sooner than not pay them, but I incline to think she won't pay this one." His mind was made up long before he reached Bellevue street. If by any sacrifice of pride or comfort he could keep the privilege of helping Judith altogether to himself, he would do so. If that were impossible he would get the money from Godfrey Hammond. But he felt doubtful whether he should like Godfrey Hammond quite as well when he should have asked and received this service at his hands. "I ought to like him all the better if he helped her when I couldn't manage it. It would be abominably unjust if I didn't. In fact, I must like him all the better for it: it stands to reason I must. I'll be shot if I should, though! and I don't much think I could ever forgive him."

Percival found that the debt was a small one, and calculated that by a miracle of economy he might pay it out of his salary at the end of the week. Consequently, he dined out two or three days: at least he did not dine at home; but his dissipation did not seem to agree with him, for he looked white and tired. Luckily, he had not to pay for his lodgings till Mrs. Bryant came back, and he sincerely hoped that the good lady would be happy with her sister, Mrs. Smith, till his finances were in better order. When he got his money he lost no time in settling Mr. Robinson's little account, and was fortunate enough to intercept another, about which Mr. Brett the tailor was growing seriously uneasy. He would not for the world have parted with the precious document, but he began to wonder how he should extricate himself from his growing embarrassments. Lydia—half suspicious, half laughing—made a remark about his continual absence from home. "You are getting to be very gay, ain't you, Mr. Thorne?" she said; and she pulled her curl with her old liveliness, and watched him while she spoke.

"Well, rather so: it does seem like it," he allowed.

"I think you'll be getting too fine for Bellevue street," said the girl: "I'm afraid we ain't scarcely smart enough for you already."

Had she any idea how much he was in their power? Was this a taunt or a chance shot?

"Oh no, I think not," he said. "You see, Miss Bryant, I'm used to Bellevue street now. By the way, I shall dine out again to-morrow."

"What! again to-morrow?" Lydia compressed her lips and looked at him. "Oh, very well: it is a fine thing to have friends make so much of one," she said as she turned to leave the room.

Percival came home late the next evening. As he passed Judith's sitting-room the door stood wide and revealed its desolate emptiness. Was she gone, absolutely gone? And he had been out and had never had a word of farewell from her! Perhaps she had looked for him in the middle of the day and wondered why he did not come. Down stairs he heard Lydia calling to the girl: "Emma, didn't I tell you to put the 'Lodgings' card up in the windows as soon as Miss Lisle was out of the house? It might just as well have been up before. What d'ye mean by leaving it lying here on the table? You're enough to provoke a saint—that you are! How d'ye know a score of people mayn't have been looking for lodgings to-day, and I dare say there won't be one to-morrow. If ever there was a lazy, good-for-nothing—" The violent slamming of the kitchen-door cut off the remainder of the discourse, but a shrill screaming voice might still be heard. Percival was certain that the tide of eloquence flowed on undiminished, though of articulate words he could distinguish none. It is to be feared that Emma was less fortunate.

It was true, then. Judith was gone, and that without a farewell look or touch of the hand to mark the day! They had lived for months under the same roof, and, though days might pass without granting them a glimpse of each other, the possibility of a meeting was continually with them. It was only that night that Percival, sitting by his cheerless fireside, understood what that possibility had been to him. He consoled himself as well as he could for his ignorance of the hour of Judith's departure by reflecting that Lydia would have followed her about with malicious watchfulness, and would either have played the spy at their interview or invented a parting instead of that which she had not seen. "She can't gossip now," thought Percival.

Meanwhile, Lydia perceived, beyond a doubt, that they must have arranged some way of meeting, since they had not taken the trouble to say "Good-bye."

[TO BE CONTINUED.]THE HARVESTING-ANTS OF FLORIDA

IN the low pine barrens of Florida are large districts thickly dotted over with small mounds made by a species of ant whose habits are unknown to the scientific world. Each mound is surrounded by a circle of small chips and pieces of charcoal, which the busy inhabitants often bring from a long distance. The hills are regular in outline, with a crater-like depression on the summit, in the centre of which is the gateway or entrance.

These ants do not live in vast communities like the mound-builders of the North, but each hill seems to be a republic by itself, though separate colonies in the same neighborhood have friendly relations with each other. Their color is rufous or reddish-brown, and they are furnished with stings like bees and wasps, and, like the honey-bee, always die after inflicting a wound, for their stings are torn from their bodies and left in the victim. The pain inflicted is about the same as that caused by the sting of the honey-bee. But they are not as vicious as most stinging insects: they will submit to considerable rough treatment before resorting to this last resource.

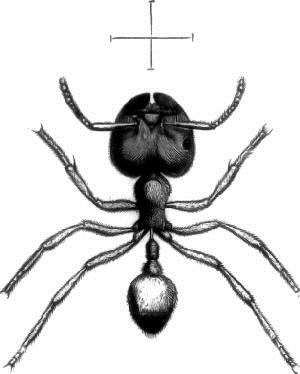

There are three sets of neuters in each colony—major and minor workers and soldiers: also one wingless queen is found in each nest. The head is very large, especially that of the soldier.1 The workers minor—which are the true workers—have regular well-defined teeth on the mandibles, while most of the soldiers have merely the rudiments or teeth entirely obsolete. All the queens which I have found—eighteen in number—have perfectly smooth mandibles, without the least vestige of a tooth.

Early in December, 1877, I brought a large colony of these ants from one of the hills, including the workers major and minor and soldiers, and established them in a glass jar which I placed in my study. They very soon commenced work, tunnelling the earth and erecting a formicary, as nearly as they could after the pattern of their home on the barrens. The mining was done entirely by the small workers. At first they refused all animal food, but ate greedily fruit and sugar, and all kinds of seeds which I gave them were immediately taken below, out of sight. I now visited the mounds on the barrens and found abundant indications of their food-supplies. At the base of each mound was a heap of chaff and shells of various kinds of seeds. The chaff was Aristida speciformis, which grew plentifully all about. I also found many seeds of Euphorbia and Croton, and several species of leguminous seeds. But the ants were not bringing seeds in at this time of year: they were only carrying out the discarded seeds and chaff; and only on the warmest days were they very active. But they do not wholly hibernate. Even after a frosty night, by ten o'clock in the morning many of the hills would be quite active.

SOLDIER.

I sent specimens to the Rev. Dr. McCook of Philadelphia to be named, and he identified them as Pogono myrmex crudelis, described by Smith as Atta crudelis2 Dr. McCook predicted from their close structural resemblance to the Texan "agricultural ant" that they would prove to be harvesting-ants.

On excavating a nest I found chambers or store-rooms filled with various kinds of seeds. But, so far as I have observed, the seeds are not eaten until they are swollen or sprouted, when the outer covering bursts of itself. At this stage the starch is being converted into sugar, and this seems to be what the ants are after. They also seemed to be very fond of the yellow pollen-dust of the pine. The catkins of the long-leaved pine (Pinus australis) commenced falling in February, and I noticed ants congregated on them; so I took those just ready to discharge the pollen, and shook the dust on the mound in little heaps, which were soon surrounded by ants, crowding and jostling each other in their eagerness to obtain a share.