Полная версия

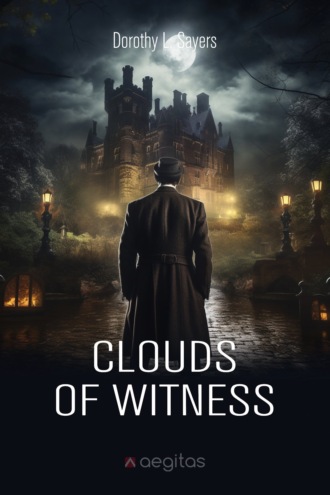

Clouds of Witness

Mr. Pettigrew-Robinson was angry, quite simply, because the detective from Scotland Yard had not accepted his help in searching the house and grounds for footprints. As an older man of some experience in these matters (Mr. Pettigrew-Robinson was a county magistrate) he had gone out of his way to place himself at the man's disposal. Not only had the man been short with him, but he had rudely ordered him out of the conservatory, where he (Mr. Pettigrew-Robinson) had been reconstructing the affair from the point of view of Lady Mary.

All these angers and embarrassments might have caused less pain to the company had they not been aggravated by the presence of the detective himself, a quiet young man in a tweed suit, eating curry at one end of the table next to Mr. Murbles, the solicitor. This person had arrived from London on Friday, had corrected the local police, and strongly dissented from the opinion of Inspector Craikes. He had suppressed at the inquest information which, if openly given, might have precluded the arrest of the Duke. He had officiously detained the whole unhappy party, on the grounds that he wanted to re-examine everybody, and was thus keeping them miserably cooped up together over a horrible Sunday; and he had put the copingstone on his offences by turning out to be an intimate friend of Lord Peter Wimsey's, and having, in consequence, to be accommodated with a bed in the gamekeeper's cottage and breakfast at the Lodge.

Mr. Murbles, who was elderly and had a delicate digestion, had travelled up in a hurry on Thursday night. He had found the inquest very improperly conducted and his client altogether impracticable. He had spent all his time trying to get hold of Sir Impey Biggs, K.C., who had vanished for the week-end, leaving no address. He was eating a little dry toast, and was inclined to like the detective who called him "Sir," and passed him the butter.

"Is anybody thinking of going to church?" asked the Duchess.

"Theodore and I should like to go," said Mrs. Pettigrew-Robinson, "if it is not too much trouble; or we could walk. It is not so very far."

"It's two and a half miles, good," said Colonel Marchbanks.

Mr. Pettigrew-Robinson looked at him gratefully.

"Of course you will come in the car," said the Duchess. "I am going myself."

"Are you, though?" said the Hon. Freddy. "I say, won't you get a bit stared at, what?"

"Really, Freddy," said the Duchess, "does that matter?"

"Well," said the Hon. Freddy, "I mean to say, these bounders about here are all Socialists and Methodists…"

"If they are Methodists," said Mrs. Pettigrew-Robinson, "they will not be at church."

"Won't they?" retorted the Hon. Freddy. "You bet they will if there's anything to see. Why, it'll be better'n a funeral to 'em."

"Surely," said Mrs. Pettigrew-Robinson, "one has a duty in the matter, whatever our private feelings may be-especially at the present day, when people are so terribly slack."

She glanced at the Hon. Freddy.

"Oh, don't you mind me, Mrs. P.," said that youth amiably. "All I say is, if these blighters make things unpleasant, don't blame me."

"Whoever thought of blaming you, Freddy?" said the Duchess.

"Manner of speaking," said the Hon. Freddy.

"What do you think, Mr. Murbles?" inquired her ladyship.

"I feel," said the lawyer, carefully stirring his coffee, "that, while your intention is a very admirable one, and does you very great credit, my dear lady, yet Mr. Arbuthnot is right in saying it may involve you in some-er-unpleasant publicity. Er-I have always been a sincere Christian myself, but I cannot feel that our religion demands that we should make ourselves conspicuous-er-in such very painful circumstances."

Mr. Parker reminded himself of a dictum of Lord Melbourne.

"Well, after all," said Mrs. Marchbanks, "as Helen so rightly says, does it matter? Nobody's really got anything to be ashamed of. There has been a stupid mistake, of course, but I don't see why anybody who wants to shouldn't go to church."

"Certainly not, certainly not, my dear," said the Colonel heartily. "We might look in ourselves, eh, dear? Take a walk that way I mean, and come out before the sermon. I think it's a good thing. Shows we don't believe old Denver's done anything wrong, anyhow."

"You forget, dear," said his wife, "I've promised to stay at home with Mary, poor girl."

"Of course, of course-stupid of me," said the Colonel. "How is she?"

"She was very restless last night, poor child," said the Duchess. "Perhaps she will get a little sleep this morning. It has been a shock to her."

"One which may prove a blessing in disguise," said Mrs. Pettigrew-Robinson.

"My dear!" said her husband.

"Wonder when we shall hear from Sir Impey," said Colonel Marchbanks hurriedly.

"Yes indeed," moaned Mr. Murbles. "I am counting on his influence with the Duke."

"Of course," said Mrs. Pettigrew-Robinson, "he must speak out-for everybody's sake. He must say what he was doing out of doors at that time. Or, if he does not, it must be discovered. Dear me! That's what these detectives are for, aren't they?"

"That is their ungrateful task," said Mr. Parker suddenly.

He had said nothing for a long time, and everybody jumped.

"There," said Mrs. Marchbanks, "I expect you'll clear it all up in no time, Mr. Parker. Perhaps you've got the real mur-the culprit up your sleeve all the time."

"Not quite," said Mr. Parker, "but I'll do my best to get him. Besides," he added, with a grin, "I'll probably have some help on the job."

"From whom?" inquired Mr. Pettigrew-Robinson.

"Her grace's brother-in-law."

"Peter?" said the Duchess. "Mr. Parker must be amused at the family amateur," she added.

"Not at all," said Parker. "Wimsey would be one of the finest detectives in England if he wasn't lazy. Only we can't get hold of him."

"I've wired to Ajaccio- poste restante," said Mr. Murbles, "but I don't know when he's likely to call there. He said nothing about when he was coming back to England."

"He's a rummy old bird," said the Hon. Freddy tactlessly, "but he oughter be here, what? What I mean to say is, if anything happens to old Denver, don't you see, he's the head of the family, ain't he-till little Pickled Gherkins comes of age."

In the frightful silence which followed this remark the sound of a walking-stick being clattered into an umbrella-stand was distinctly audible.

"Who's that, I wonder," said the Duchess.

The door waltzed open.

"Mornin', dear old things," said the newcomer cheerfully. "How are you all? Hullo, Helen! Colonel you owe me half a crown since last September year. Mornin', Mrs. Marchbanks, Mornin' Mrs. P. Well, Mr. Murbles, how d'you like this bill-beastly weather? Don't trouble to get up, Freddy; I'd simply hate to inconvenience you. Parker, old man, what a damned reliable old bird you are! Always on the spot, like that patent ointment thing. I say, have you all finished? I meant to get up earlier, but I was snorin' so Bunter hadn't the heart to wake me. I nearly blew in last night, only we didn't arrive till 2 A.M. and I thought you wouldn't half bless me if I did. Eh, what, Colonel? Aeroplane. Victoria from Paris to London-North-Eastern to Northallerton-damn bad roads the rest of the way, and a puncture just below Riddlesdale. Damn bad bed at the 'Lord in Glory'; thought I'd blow in for the last sausage here, if I was lucky. What? Sunday morning in an English family and no sausages? God bless my soul, what's the world coming to, eh, Colonel? I say, Helen, old Gerald's been an' gone an' done it this time, what? You've no business to leave him on his own, you know; he always gets into mischief. What's that? Curry? Thanks, old man. Here, I say, you needn't be so stingy about it; I've been travelling for three days on end. Freddy, pass the toast. Beg pardon, Mrs. Marchbanks? Oh, rather, yes; Corsica was perfectly amazin'-all black-eyed fellows with knives in their belts and jolly fine-looking girls. Old Bunter had a regular affair with the inn-keeper's daughter in one place. D'you know, he's an awfully susceptible old beggar. You'd never think it, would you? Jove! I am hungry. I say, Helen, I meant to get you some fetchin' crepe-de-Chine undies from Paris, but I saw that old Parker was gettin' ahead of me over the bloodstains, so we packed up our things and buzzed off."

Mrs. Pettigrew-Robinson rose.

"Theodore," she said, "I think we ought to be getting ready for church."

"I will order the car," said the Duchess. "Peter, of course I'm exceedingly glad to see you. Your leaving no address was most inconvenient. Ring for anything you want. It is a pity you didn't arrive in time to see Gerald."

"Oh, that's all right," said Lord Peter cheerfully; "I'll look him up in quod. Y'know it's rather a good idea to keep one's crimes in the family; one has so many more facilities. I'm sorry for poor old Polly, though. How is she?"

"She must not be disturbed to-day," said the Duchess with decision.

"Not a bit of it," said Lord Peter; "she'll keep. Today Parker and I hold high revel. To-day he shows me all the bloody footprints-it's all right, Helen, that's not swearin', that's an adjective of quality. I hope they aren't all washed away, are they, old thing?"

"No," said Parker, "I've got most of them under flowerpots."

"Then pass the bread and squish," said Lord Peter, "and tell me all about it."

The departure of the church-going element had induced a more humanitarian atmosphere. Mrs. Marchbanks stumped off upstairs to tell Mary that Peter had come, and the Colonel lit a large cigar.

The Hon. Freddy rose, stretched himself, pulled a leather arm-chair to the fireside, and sat down with his feet on the brass fender, while Parker marched round and poured himself out another cup of coffee.

"I suppose you've seen the papers," he said.

"Oh, yes, I read up the inquest," said Lord Peter.

"Y'know, if you'll excuse my saying so, I think you rather mucked it between you."

"It was disgraceful," said Mr. Murbles, "disgraceful. The Coroner behaved most improperly. He had no business to give such a summing-up. With a jury of ignorant country fellows, what could one expect? And the details that were allowed to come out! If I could have got here earlier-"

"I'm afraid that was partly my fault, Wimsey," said Parker penitently. "Craikes rather resents me. The Chief Constable at Stapley sent to us over his head, and when the message came through I ran along to the Chief and asked for the job, because I thought if there should be any misconception or difficulty, you see, you'd just as soon I tackled it as anybody else. I had a few little arrangements to make about a forgery I've been looking into, and, what with one thing and another, I didn't get off till the night express. By the time I turned up on Friday, Craikes and the Coroner were already as thick as thieves, had fixed the inquest for that morning-which was ridiculous-and arranged to produce their blessed evidence as dramatically as possible. I only had time to skim over the ground (disfigured, I'm sorry to say, by the prints of Craikes and his local ruffians), and really had nothing for the jury."

"Cheer up," said Wimsey. "I'm not blaming you. Besides, it all lends excitement to the chase."

"Fact is," said the Hon. Freddy, "that we ain't popular with respectable Coroners. Giddy aristocrats and immoral Frenchmen. I say, Peter, sorry you've missed Miss Lydia Cathcart. You'd have loved her. She's gone back to Golders Green and taken the body with her."

"Oh, well," said Wimsey. "I don't suppose there was anything abstruse about the body."

"No," said Parker, "the medical evidence was all right as far as it went. He was shot through the lungs, and that's all."

"Though, mind you," said the Hon. Freddy, "he didn't shoot himself. I didn't say anything, not wishin' to upset old Denver's story, but, you know, all that stuff about his bein' so upset and go-to-blazes in his manner was all my whiskers."

"How do you know?" said Peter.

"Why, my dear man, Cathcart'n I toddled up to bed together. I was rather fed up, havin' dropped a lot on some shares, besides missin' everything I shot at in the mornin', an' lost a bet I made with the Colonel about the number of toes on the kitchen cat, an' I said to Cathcart it was a hell of a damn-fool world, or words to that effect. 'Not a bit of it,' he said; 'it's a damn good world. I'm goin' to ask Mary for a date to-morrow, an' then we'll go and live in Paris, where they understand sex.' I said somethin' or other vague, and he went off whistlin'."

Parker looked grave. Colonel Marchbanks cleared his throat.

"Well, well," he said, "there's no accounting for a man like Cathcart, no accounting at all. Brought up in France, you know. Not at all like a straightforward Englishman. Always up and down, up and down! A sad, poor fellow. Well, well, Peter, hope you and Mr. Parker will find out something about it. We mustn't have poor old Denver cooped up in gaol like this, you know. Awfully unpleasant for him, poor chap, and with the birds so good this year. Well, I expect you'll be making a tour of inspection, eh, Mr. Parker? What do you say to shoving the balls about a bit, Freddy?"

"Right you are," said the Hon. Freddy; "you'll have to give me a hundred, though, Colonel."

"Nonsense, nonsense," said that veteran, in high good humour; "you play an excellent game."

Mr. Murbles having withdrawn, Wimsey and Parker faced each other over the remains of the breakfast.

"Peter," said the detective, "I don't know if I've done the right thing by coming. If you feel-"

"Look here, old man," said his friend earnestly, "let's cut out the considerations of delicacy. We're goin' to work this case like any other. If anything unpleasant turns up, I'd rather you saw it than anybody else. It's an uncommonly pretty little case, on its merits, and I'm goin' to put some damn good work into it."

"If you're sure it's all right-"

"My dear man, if you hadn't been here I'd have sent for you. Now let's get to business. Of course, I'm settin' off with the assumption that old Gerald didn't do it."

"I'm sure he didn't," agreed Parker.

"No, no," said Wimsey, "that isn't your line. Nothing rash about you-nothing trustful. You are expected to throw cold water on my hopes and doubt all my conclusions."

"Right ho!" said Parker. "Where would you like to begin?"

Peter considered. "I think we'll start from Cathcart's bedroom," he said.

The bedroom was of moderate size, with a single window overlooking the front door. The bed was on the right-hand side, the dressing-table before the window. On the left was the fireplace, with an arm-chair before it, and a small writing-table.

"Everything's as it was," said Parker. "Craikes had that much sense."

"Yes," said Lord Peter. "Very well. Gerald says that when he charged Cathcart with bein' a scamp, Cathcart jumped up, nearly knockin' the table over. That's the writin'-table, then, so Cathcart was sittin' in the arm-chair. Yes, he was-and he pushed it back violently and rumpled up the carpet. See! So far, so good. Now what was he doin' there? He wasn't readin', because there's no book about, and we know that he rushed straight out of the room and never came back. Very good. Was he writin'? No, virgin sheet of blottin'-paper-"

"He might have been writing in pencil," suggested Parker.

"That's true, old Kill-Joy, so he might. Well, if he was he shoved the paper into his pocket when Gerald came in, because it isn't here; but he didn't, because it wasn't found on his body; so he wasn't writing."

"Unless he threw the paper away somewhere else," said Parker. "I haven't been all over the grounds, you know, and at the smallest computation-if we accept the shot heard by Hardraw at 11.50 as the shot-there's an hour and a half unaccounted for."

"Very well. Let's say there is nothing to show he was writing. Will that do? Well, then-"

Lord Peter drew out a lens and scrutinised the surface of the arm-chair carefully before sitting down in it.

"Nothing helpful there," he said. "To proceed, Cathcart sat where I am sitting. He wasn't writing-you're sure this room hasn't been touched?"

"Certain."

"Then he wasn't smoking."

"Why not? He might have chucked the stub of a cigar or cigarette into the fire when Denver came in."

"Not a cigarette," said Peter, "or we should find traces somewhere-on the floor or in the grate. That light ash blows about so. But a cigar-well, he might have smoked a cigar without leaving a sign, I suppose. But I hope he didn't."

"Why?"

"Because, old son, I'd rather Gerald's account had some element of truth in it. A nervy man doesn't sit down to the delicate enjoyment of a cigar before bed, and cherish the ash with such scrupulous care. On the other hand, if Freddy's right, and Cathcart was feelin' unusually sleek and pleased with life, that's just the sort of thing he would do."

"Do you think Mr. Arbuthnot would have invented all that, as a matter of fact?" said Parker thoughtfully. "He doesn't strike me that way. He'd have to be imaginative and spiteful to make it up, and I really don't think he's either."

"I know," said Lord Peter. "I've known old Freddy all my life, and he wouldn't hurt a fly. Besides, he simply hasn't the wits to make up any sort of a story. But what bothers me is that Gerald most certainly hasn't the wits either to invent that Adelphi drama between him and Cathcart."

"On the other hand," said Parker, "if we allow for a moment that he shot Cathcart, he had an incentive to invent it. He would be trying to get his head out of the-I mean, when anything important is at stake it's wonderful how it sharpens one's wits. And the story being so farfetched does rather suggest an unpractised storyteller."

"True O King. Well, you've sat on all my discoveries so far. Never mind. My head is bloody but unbowed. Cathcart was sitting here-"

"So your brother said."

"Curse you, I say he was; at least, somebody was; he's left the impression of his sit-me-down-upon on the cushion."

"That might have been earlier in the day."

"Rot. They were out all day. You needn't overdo this Sadducee attitude, Charles. I say Cathcart was sitting here, and-hullo! hullo!"

He leaned forward and stared into the grate.

"There's some burnt paper here, Charles."

"I know. I was frightfully excited about that yesterday, but I found it was just the same in several of the rooms. They often let the bedroom fires go out when everybody's out during the day, and relight them about an hour before dinner. There's only the cook, housemaid, and Fleming here, you see, and they've got a lot to do with such a large party."

Lord Peter was picking the charred fragments over.

"I can find nothing to contradict your suggestion," he sadly said, "and this fragment of the Morning Post rather confirms it. Then we can only suppose that Cathcart sat here in a brown study, doing nothing at all. That doesn't get us much further, I'm afraid." He got up and went to the dressing-table.

"I like these tortoiseshell sets," he said, "and the perfume is 'Kaiser du Soir'-very nice too. New to me. "Must draw Bunter's attention to it. A charming manicure set, isn't it? You know, I like being clean and all that, but Cathcart was the kind of man who always impressed you as bein' just a little too well turned out. Poor devil! And he'll be buried at Golders Green after all. I only saw him once or twice, you know. He impressed me as knowin' about everything there was to know. I was rather surprised at Mary's takin' to him, but, then, I know really awfully little about Mary. You see, she's five years younger than me. When the war broke out she'd just left school and gone to a place in Paris, and I joined up, and she came back and did nursing and social work, so I only saw her occasionally. At that time she was rather taken up with new schemes for puttin' the world to rights and hadn't a lot to say to me. And she got hold of some pacifist fellow who was a bit of a stumer, I fancy. Then I was ill, you know, and after I got the chuck from Barbara I didn't feel much like botherin' about other people's heart-to-hearts, and then I got mixed up in the Attenbury diamond case-and the result is I know uncommonly little about my own sister. But it looks as though her taste in men had altered. I know my mother said Cathcart had charm; that means he was attractive to women, I suppose. No man can see what makes that in another man, but mother is usually right. What's become of this fellow's papers?"

"He left very little here," replied Parker. "There's a cheque-book on Cox's Charing Cross branch, but it's a new one and not very helpful. Apparently he only kept a small current account with them for convenience when he was in England. The cheques are mostly to self, with an occasional hotel or tailor."

"Any pass-book?"

"I think all his important papers are in Paris. He has a flat there, near the river somewhere. We're in communication with the Paris police. He had a room in Albany. I've told them to lock it up till I get there. I thought of running up to town tomorrow."

"Yes you'd better. Any pocket-book?"

"Yes; here you are. About £30 in various notes, a wine-merchant's card, and a bill for a pair of riding-breeches."

"No correspondence?"

"Not a line."

"No," said Wimsey, "he was the kind, I imagine, that didn't keep letters. Much too good an instinct of self-preservation."

"Yes. I asked the servants about his letters, as a matter of fact. They said he got a good number, but never left them about. They couldn't tell me much about the ones he wrote, because all the outgoing letters are dropped into the post-bag, which is carried down to the post-office as it is and opened there, or handed over to the postman when-or if-he calls. The general impression was that he didn't write much. The housemaid said she never found anything to speak of in the waste-paper basket."

"Well, that's uncommonly helpful. Wait a moment. Here's his fountain-pen. Very handsome-Onoto with complete gold casing. Dear me! entirely empty. Well, I don't know that one can deduce anything from that, exactly. I don't see any pencil about, by the way. I'm inclined to think you're wrong in supposing that he was writing letters."

"I didn't suppose anything," said Parker mildly. "I daresay you're right."

Lord Peter left the dressing-table, looked through the contents of the wardrobe, and turned over the two or three books on the pedestal beside the bed.

" La Patisserie de la Heine Pedauque, L'Anneau d'Amethyste, South Wind (our young friend works out very true to type), Chronique d'un Cadet de Contras (tut-tut, Charles!') Manon Lescaut. H'm! Is there anything else in this room I ought to look at?"

"I don't think so. Where'd you like to go now?"

"We'll follow 'em down. Wait a jiff. Who are in the other rooms? Oh, yes. Here's Gerald's room. Helen's at church. In we go. Of course, this has been dusted and cleaned up, and generally ruined for purposes of observation?"

"I'm afraid so. I could hardly keep the Duchess out of her bedroom."

"No. Here's the window Gerald shouted out of. H'm! Nothing in the grate here, naturally-the fire's been lit since. I say, I wonder where Gerald did put that letter to-Freeborn's, I mean."

"Nobody's been able to get a word out of him about it," said Parker. "Old Mr. Murbles had a fearful time with him. The Duke insists simply that he destroyed it. Mr. Murbles says that's absurd. So it is. If he was going to bring that sort of accusation against his sister's fiancé he'd want some evidence of a method in his madness, wouldn't he? Or was he one of those Roman brothers who say simply: 'As the head of the family I forbid the banns and that's enough'?"

"Gerald," said Wimsey, "is a good, clean, decent, thoroughbred public schoolboy, and a shocking ass. But I don't think he's so mediaeval as that."

"But if he has the letter, why not produce it?"

"Why, indeed? Letters from old college friends in Egypt aren't, as a rule, compromising."

"You don't suppose," suggested Parker tentatively, "that this Mr. Freeborn referred in his letter to any old-er-entanglement which your brother wouldn't wish the Duchess to know about?"

Lord Peter paused, while absently examining a row [missing] "That's an idea," he said. "There were occasions-mild ones, but Helen would make the most of them."