Полная версия

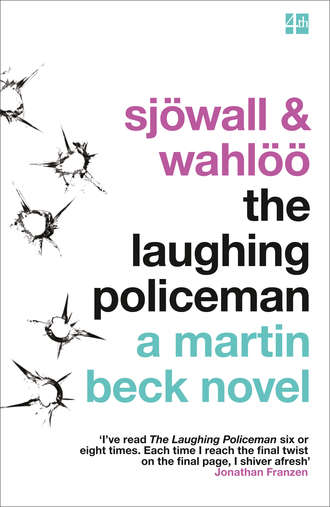

The Laughing Policeman

‘Sat’ was perhaps not the right word. Stenström's dark-blue poplin raincoat was soaked with blood and he sprawled in his seat, his right shoulder against the back of a young woman who was sitting next to him, bent double.

He was dead. Like the young woman and the six other people in the bus.

In his right hand he held his service pistol.

7

The rain kept on all night and although the sun, according to the almanac, rose at twenty minutes to eight the time was nearer nine before it was strong enough to penetrate the clouds and disseminate an uncertain, hazy light.

Across the pavement on Norra Stationsgatan stood the red doubledecker bus just as it had stopped ten hours previously.

But that was the only thing that was the same. By now about fifty men were inside the extensive cordons, and outside them the crowd of curious onlookers got bigger and bigger. Many had been standing there ever since midnight, and all they had seen was police and ambulance men and wailing emergency vehicles of every conceivable kind. It had been a night of sirens, with a constant stream of cars roaring along the wet streets, apparently going nowhere and for no reason.

Nobody knew anything for sure, but there were two words that were whispered from person to person and soon spread in concentric circles through the crowd and the surrounding houses and city, finally taking more definite shape and being flung out across the country as a whole. By now the words had reached far beyond the frontiers.

Mass murder.

Mass murder in Stockholm.

Mass murder in a bus in Stockholm.

Everybody thought they knew this much at least.

Very little more was known at police headquarters on Kungsholmsgatan. It wasn't even known for certain who was in charge of the investigation. The confusion was complete. Telephones rang incessantly, people came and went, floors were dirtied and the men who dirtied them were irritable and clammy with sweat and rain.

‘Who's working on the list of names?’ Martin Beck asked.

‘Rönn, I should think,’ said Kollberg without turning round. He was busy taping a plan to the wall. The sketch was over three yards long and more than half a yard wide and was awkward to handle.

‘Can't someone give me a hand?’ he said.

‘Sure,’ said Melander calmly, putting down his pipe and standing up.

Fredrik Melander was a tall, lean man of grave appearance and methodical disposition. He was forty-eight years old and a detective inspector on the homicide squad. Kollberg had worked together with him for many years. He had forgotten how many. Melander, on the other hand, had not. He was known never to forget anything.

Two telephones rang.

‘Hello. This is Superintendent Beck. Who? No, he's not here. Shall I ask him to call? Oh, I see.’

He put the phone down and reached for the other one. An almost white-haired man of about fifty opened the door cautiously and stopped doubtfully on the threshold.

‘Well, Ek, what do you want?’ Martin Beck asked as he lifted the receiver.

‘About the bus …’ the white-haired man said.

‘When will I be home? I haven't the vaguest idea,’ said Martin Beck into the telephone.

‘Hell,’ Kollberg exclaimed as the strip of tape got tangled up between his fat fingers.

‘Take it easy,’ Melander said.

Martin Beck turned back to the man in the doorway.

‘Well, what about the bus?’

Ek shut the door behind him and studied his notes.

‘It's built by the Leyland factories in England,’ he said. ‘It's an Atlantean model, but here it's called Type H35. It holds seventy-five seated passengers. The odd thing is –’

The door was flung open. Gunvald Larsson stared incredulously into his untidy office. His light raincoat was sopping wet, like his trousers and his fair hair. His shoes were muddy.

‘What a bloody mess in here,’ he grumbled.

‘What was the odd thing about the bus?’ Melander asked.

‘Well, that particular type isn't used on route 47.’

‘Isn't it?’

‘Not as a rule, I mean. They usually put German buses on, made by Büssing. They're also doubledeckers. This was just an exception.’

‘A brilliant clue,’ Gunvald Larsson said. ‘The madman who did this only murders people in English buses. Is that what you mean?’

Ek looked at him resignedly. Gunvald Larsson shook himself and said, ‘By the way, what's the horde of apes doing down in the vestibule? Who are they?’

‘Journalists,’ Ek said. ‘Someone ought to talk to them.’

‘Not me,’ Kollberg said promptly.

‘Isn't Hammar or the Commissioner or the Attorney General or some other higher-up going to issue a communiqué?’ Gunvald Larsson said.

‘It probably hasn't been worded yet,’ said Martin Beck. ‘Ek is right. Someone ought to talk to them.’

‘Not me,’ Kollberg repeated.

Then he wheeled round, almost triumphantly, as if he had had a brainwave.

‘Gunvald,’ he said. ‘You were the one who got there first. You can hold the press conference.’

Gunvald Larsson stared into the room and pushed a wet tuft of hair off his forehead with the back of his big hairy right hand. Martin Beck said nothing, not even bothering to look towards the door.

‘OK,’ Gunvald Larsson said. ‘Get them herded in somewhere. I'll talk to them. There's just one thing I must know first.’

‘What?’ Martin Beck asked.

‘Has anyone told Stenström's mother?’

Dead silence fell, as though the words had robbed everyone in the room of the power of speech, including Gunvald Larsson himself. The man on the threshold looked from one to the other.

At last Melander turned his head and said, ‘Yes. She's been told.’

‘Good,’ Gunvald Larsson said, and banged the door.

‘Good,’ said Martin Beck to himself, drumming the top of the desk with his fingertips.

‘Was that wise?’ Kollberg asked.

‘What?’

‘Letting Gunvald … Don't you think we'll get enough abuse in the press as it is?’

Martin Beck looked at him but said nothing. Kollberg shrugged.

‘Oh well,’ he said. ‘It doesn't matter.’

Melander went back to the desk, picked up his pipe and lit it.

‘No,’ he said. ‘It couldn't matter less.’

He and Kollberg had got the sketch up now. An enlarged drawing of the lower deck of the bus. Some figures were sketched in. They were numbered from one to nine.

‘Where's Rönn with that list?’ Martin Beck mumbled.

‘Another thing about the bus –’ Ek said obstinately.

And the telephones rang.

8

The office where the first improvised confrontation with the press took place was decidedly ill-suited to the purpose. It contained nothing but a table, a few cupboards and four chairs, and when Gunvald Larsson entered the room, it was already stuffy with cigarette smoke and the smell of wet overcoats.

He stopped just inside the door, looked round at the assembled journalists and photographers and said tonelessly, ‘Well, what do you want to know?’

They all began to talk at once. Gunvald Larsson held up his hand and said, One at a time, please. You, there, can start. Then we'll go from left to right.'

Thereafter the press conference proceeded as follows:

QUESTION: When was the bus found?

ANSWER: About ten minutes past eleven last night.

Q: By whom?

A: A man in the street who then stopped a radio patrol car.

Q: How many were in the bus?

A: Eight.

Q: Were they all dead?

A: Yes.

Q: How had they died?

A: It's too soon yet to say.

Q: Was their death caused by external violence?

A: Probably.

Q: What do you mean by probably?

A: Exactly what I say.

Q: Were there any signs of shooting?

A: Yes.

Q: So all these people had been shot dead?

A: Probably.

Q: So it's really a question of mass murder?

A: Yes.

Q: Have you found the murder weapon?

A: No.

Q: Have the police detained anyone yet?

A: No.

Q: Are there any traces or clues that point to one particular person?

A: No.

Q: Were the murders committed by one and the same person?

A: Don't know.

Q: Is there anything to indicate that more than one person killed these eight people?

A: No.

Q: How could one single person kill eight people in a bus before anyone had time to resist?

A: Don't know.

Q: Were the shots fired by someone inside the bus or did they come from outside?

A: They did not come from outside.

Q: How do you know?

A: The windowpanes that were damaged had been fired at from inside.

Q: What kind of weapon had the murderer used?

A: Don't know.

Q: It must surely have been a machine gun or a submachine gun?

A: No comment.

Q: Was the bus standing still when the murders were committed or was it moving?

A: Don't know.

Q: Doesn't the position in which the bus was found indicate that the shooting took place while it was in movement and that it then mounted the pavement?

A: Yes.

Q: Did the police dogs get a scent?

A: It was raining.

Q: It was a doubledecker bus, wasn't it?

A: Yes.

Q: Where were the bodies found? On the upper or lower deck?

A: On the lower one.

Q: All eight?

A: Yes.

Q: Have the victims been identified?

A: No.

Q: Has any of them been identified?

A: Yes.

Q: Who? The driver?

A: No. A policeman.

Q: A policeman? Can we have his name?

A: Yes. Detective Sub-inspector Åke Stenström.

Q: Stenström? From the homicide squad?

A: Yes.

A couple of the reporters tried to push towards the door, but Gunvald Larsson again put up his hand.

‘No running back and forth, if you don't mind,’ he said. ‘Any more questions?’

Q: Was Inspector Strenström one of the passengers in the bus?

A: He wasn't driving at any rate.

Q: Do you consider he was there just by chance?

A: Don't know.

Q: The question was put to you personally. Do you consider it a mere chance that one of the victims is a man from the CID?

A: I have not come here to answer personal questions.

Q: Was Inspector Stenström working on any special investigation when this happened?

A: Don't know.

Q: Was he on duty last night?

A: No.

Q: He was off duty?

A: Yes.

Q: Then he must have been there by chance. Can you name any of the other victims?

A: No.

Q: This is the first time a real mass murder has occurred in Sweden. On the other hand there have been several similar crimes abroad in recent years. Do you think that this maniacal act was inspired by what happened in America, for instance?

A: Don't know.

Q: Is it the opinion of the police that the murderer is a madman who wants to draw sensational attention to himself?

A: That is one theory.

Q: Yes, but it doesn't answer my question. Are the police working on the lines of that theory?

A: All clues and suggestions are being followed.

Q: How many of the victims are women?

A: Two.

Q: So six of the victims are men?

A: Yes.

Q: Including the bus driver and Inspector Stenström?

A: Yes.

Q: Just a minute, now. We've been told that one of the people in the bus survived and was taken away in an ambulance that arrived on the scene before the police had had time to cordon off the area.

A: Oh?

Q: Is this true?

A: Next question.

Q: Apparently you were one of the first policemen to arrive on the scene?

A: Yes.

Q: What time did you get there?

A: At eleven twenty-five.

Q: What did it look like inside the bus just then?

A: What do you think?

Q: Can you say it was the most ghastly sight you've ever seen in your life?

Gunvald Larsson stared vacantly at the questioner, who was quite a young man with round, steel-rimmed glasses and a somewhat unkempt red beard. At last he said, ‘No. I can't.’

The reply caused some bewilderment. One of the woman journalists frowned and said lamely and incredulously, ‘What do you mean by that?’

‘Exactly what I say.’

Before joining the police force Gunvald Larsson had been a regular seaman in the navy. In August, 1943, he had been one of those to go through the submarine Ulven, which had struck a mine and had been salvaged after having lain on the seabed for three months. Several of the thirty-three killed had been on the same courses with him. After the war, one of his duties had been to help with the extradition of the Baltic collaborators from the camp at Ränneslätt. He had also seen the arrival of thousands of victims who had been repatriated from the German concentration camps. Most of these had been women and many of them had not survived.

However, he saw no reason to explain himself to this youthful assembly but said laconically, ‘Any more questions?’

‘Have the police been in touch with any witnesses of the actual event?’

‘No.’

‘In other words, a mass murder has been committed in the middle of Stockholm. Eight people have been killed, and that's all the police have to say?’

‘Yes.’

With that, the press conference was concluded.

9

It was some time before anyone noticed that Rönn had come in with the list. Martin Beck, Kollberg, Melander and Gunvald Larsson stood leaning over one of the tables, which was littered with photographs from the scene of the crime, when Rönn suddenly stood next to them and said, ‘It's ready now, the list.’

He was born and raised in Arjeplog and although he had lived in Stockholm for more than twenty years he had still kept his north-Swedish dialect.

He laid the list on a corner of the table, drew up a chair and sat down.

‘Don't go around frightening people,’ Kollberg said.

It had been silent in the room for so long that he had started at the sound of Rönn's voice.

‘Well, let's see,’ Gunvald Larsson said impatiently, reaching for the list.

He looked at it for a while. Then he handed it back to Rönn.

‘That's about the most cramped writing I've ever seen. Can you really read that yourself? Haven't you typed out any copies?’

‘Yes,’ Rönn replied. ‘I have. You'll get them in a minute.’

‘OK,’ said Kollberg. ‘Let's hear.’

Rönn put on his glasses and cleared his throat. He glanced through his notes.

Of the eight dead, four lived in the vicinity of the terminus,' he began. ‘The survivor also lived there.’

‘Take them in order if you can,’ Martin Beck said.

‘Well, first of all there's the driver. He was hit by two shots in the back of the neck and one in the back of the head and must have been killed outright.’

Martin Beck had no need to look at the photograph that Rönn extracted from the pile on the table. He remembered all too well how the man in the driver's seat had looked.

‘The driver's name was Gustav Bengtsson. He was forty-eight, married, two children, lived at Inedalsgatan 5. His family has been notified. It was his last run for the day and when he had let off the passengers at the last stop he would have driven the bus to the Hornsberg depot at Lindhagensgatan. The money in his fare purse was untouched and in his wallet he had 120 kronor.’

He glanced at the others over his glasses.

‘There's no more about him for the moment.’

‘Go on,’ Melander said.

‘I'll take them in the same order as on the sketch. The next is Åke Stenström. Five shots in the back. One in the right shoulder from the side, might have been a ricochet. He was twenty-nine and lived –’

Gunvald Larsson interrupted him.

‘You can skip that. We know where he lived.’

‘I didn't,’ Rönn said.

‘Go on,’ said Melander.

Rönn cleared his throat.

‘He lived on Tjärhovsgatan together with his fiancée …’

Gunvald Larsson interrupted him again.

‘They were not engaged. I asked him not long ago.’

Martin Beck cast an irritated glance at Gunvald Larsson and nodded to Rönn to continue.

‘Together with Åsa Torell, twenty-four. She works at a travel agency.’

He gave Gunvald Larsson a quick look and said, ‘In sin. I don't know whether she's been told.’

Melander took his pipe out of his mouth and said, ‘She has been told.’

None of the five men around the table looked at the pictures of Stenström's mutilated body. They had already seen them and preferred not to see them again.

‘In his right hand he held his service pistol. It was cocked but he had not fired a shot. In his pockets he had a wallet containing 37 kronor, identification card, a snapshot of Åsa Torell, a letter from his mother and some receipts. Also, driving licence, notebook, pens and bunch of keys. It will all be sent up to us when the boys at the lab are through with it. Can I go on?’

‘Yes, please,’ said Kollberg.

‘The girl in the seat next to Stenström was called Britt Danielsson. She was twenty-eight, unmarried and worked at Sabbatsberg Hospital. She was a registered nurse.’

‘I wonder whether they were together,’ Gunvald Larsson said. ‘Perhaps he was having a bit of fun on the side.’

Rönn looked at him disapprovingly.

‘We'd better find out,’ Kollberg said.

‘She shared a room at Karlbergsvägen 87 with another nurse from Sabbatsberg. According to her roommate, Monika Granholm by name, Britt Danielsson was coming straight from the hospital. She was hit by one shot. In the temple. She was the only one in the bus to be struck by only one bullet. She had thirty-eight different things in her handbag. Shall I enumerate them?’

‘Christ, no,’ said Gunvald Larsson.

‘Number four on the list and on the sketch is Alfons Schwerin, the survivor. He was lying on his back on the floor between the two longitudinal seats at the rear. You already know his injuries. He was hit in the abdomen and one bullet lodged in the region of the heart. He lives alone at Norra Stationsgatan 117. He is forty-three and employed by the highway department of the city council. How is he, by the way?’

‘Still in a coma,’ Martin Beck said. ‘The doctors say there's just a chance he'll regain consciousness. But if he does they don't know whether he'll be able to talk or even to remember anything.’

‘Can't you talk with a bullet in your belly?’ Gunvald Larsson asked.

‘Shock,’ said Martin Beck.

He pushed back his chair and stretched himself. Then he lit a cigarette and stood in front of the sketch.

‘What about this one in the corner?’ he said. ‘Number eight?’

He pointed to the seat at the very back of the bus in the right-hand corner. Rönn consulted his notes.

‘He got eight bullets in him. In the chest and abdomen. He was an Arab and his name was Mohammed Boussie, Algerian subject, thirty-six, no relations in Sweden. He lived at a kind of boarding house on Norra Stationsgatan. Was obviously on his way home from work at the Zig-Zag, that grill restaurant on Vasagatan. There's nothing more to say about him at the moment.’

‘Arabia,’ said Gunvald Larsson. ‘Isn't that where there's usually an awful lot of shooting?’

‘Your political knowledge is devastating,’ Kollberg said. ‘You should apply for a transfer to Sepo.’

‘Its correct name is the Security Department of the National Police Board,’ said Gunvald Larsson.

Rönn got up, fished one or two pictures out of the pile and lined them up on the table.

‘This guy we haven't been able to identify,’ he said. ‘Number six. He was sitting on the outside seat immediately behind the middle doors and was hit by six shots. In his pockets he had the striking surface of a matchbox, a packet of Bill cigarettes, a bus ticket and 1,823 kronor in cash. That was all.’

‘A lot of money,’ Melander said thoughtfully.

They leaned over the table and studied the pictures of the unknown man. He had slithered down in the seat and lay sprawled against the back with arms hanging and his left leg stuck out in the aisle. The front of his coat was soaked in blood. He had no face.

‘Hell, it would have to be him,’ Gunvald Larsson said. ‘His own mother wouldn't recognize him.’

Martin Beck had resumed his study of the sketch on the wall. Holding his left hand in front of his face he said, ‘I'm not so sure there weren't two of them after all.’

The others looked at him.

‘Two what?’ Gunvald Larsson asked.

‘Two gunmen. Look at all the passengers, they never moved from their seats. Except the one who's still alive and he might have tumbled off afterwards.’

‘Two madmen?’ Gunvald Larsson said sceptically. ‘At the same time?’

Kollberg went and stood beside Martin Beck.

‘You mean that someone should have had time to react if there had been only one? Hm, maybe. But he simply mowed them down. It happened rather fast, and when you think they were all caught napping …’

‘Shall we go on with the list? We'll find that out as soon as we know whether there was one weapon or two.’

‘Sure,’ said Martin Beck. ‘Go on, Einar.’

‘Number seven is a foreman called Johan Källström. He was sitting beside the man who has not yet been identified. He was fifty-two, married and lived at Karlbergsvägen 89. According to his wife he was coming from the workshop on Sibyllegatan, where he'd been working overtime. Nothing startling about him.’

‘Nothing except that he got a bellyful of lead on the way home from work,’ said Gunvald Larsson.

‘By the window immediately in front of the middle doors we have Gösta Assarsson, number eight. Forty-two. Half his head was shot away. He lived at Tegnérgatan 40, where he also had his office and his business, an export and import firm that he ran together with his brother. His wife didn't known why he was on the bus. According to her, he should have been at a club meeting on Narvavägen.’

‘A-ha,’ said Gunvald Larsson. ‘Out carousing.’

‘Yes, there are signs that point to that. In his briefcase he had a bottle of whisky. Johnnie Walker, Black Label.’

‘A-ha,’ said Kollberg, who was an epicure.

‘In addition he was well supplied with condoms,’ said Rönn. ‘He had seven in an inside pocket. Plus a chequebook and over 800 kronor in cash.’

‘Why seven?’ Gunvald Larsson asked.

The door opened and Ek stuck his head in.

‘Hammar says you're all to be in his office in fifteen minutes. Briefing. Quarter to eleven, that's to say.’

He disappeared.

‘OK, let's go on,’ Martin Beck said.

‘Where were we?’

‘The guy with the seven johnnies,’ said Gunvald Larsson.

‘Is there anything more to be said about him?’ Martin Beck asked.

Rönn glanced at the sheet of paper covered with his scribbling.

‘I don't think so.’

‘Go on, then,’ said Martin Beck, sitting down at Gunvald Larsson's desk.

‘Two seats in front of Assarsson sat number nine, Mrs Hildur Johansson, sixty-eight, widow, living at Norra Stationsgatan 119. Shot in the shoulder and through the neck. She has a married daughter on Västmannagatan and was on her way home from there after baby-sitting.’

Rönn folded the piece of paper and tucked it into his jacket pocket.

‘That's the lot,’ he said.

Gunvald Larsson sighed and arranged the pictures in nine neat stacks.

Melander put his pipe down, mumbled something and went out to the toilet.

Kollberg tilted his chair and said, ‘And what do we learn from all this? That on quite an ordinary evening on quite an ordinary bus, nine quite ordinary people get mowed down with a submachine gun for no apparent reason. Apart from this guy who hasn't been identified, I can't see anything odd about any of these people.’