Полная версия

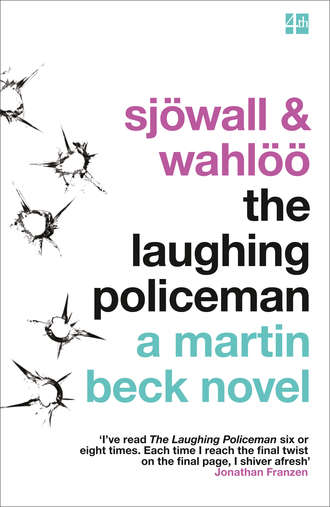

The Laughing Policeman

MAJ SJÖWALL

AND PER WAHLÖÖ

The Laughing Policeman

Translated from the Swedish by Alan Blair

Copyright

This novel is entirely a work of fiction. The names, characters and incidents portrayed in it are the work of the author's imagination. Any resemblance to actual persons living or dead, events or localities is entirely coincidental.

4th Estate

An imprint of HarperCollinsPublishers Ltd. 1 London Bridge Street London SE1 9GF

www.harpercollins.co.uk

This ebook first published by Harper Perennial in 2007

This 4th Estate edition published in 2016

This translation first published by Random House Inc, New York, in 1970

Originally published in Sweden by P. A. Norstedt & Soners Forlag

Copyright text © Maj Sjöwall and Per Wahlöö 1968

Copyright introduction © Jonathan Franzen 2009

Cover photograph © Shutterstock

PS Section © Richard Shephard 2007

PS™ is a trademark of HarperCollinsPublishers Ltd.

Maj Sjöwall and Per Wahlöö assert the moral right to be identified as the authors of this work

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the non-exclusive, non-transferable right to access and read the text of this ebook on-screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, down-loaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins ebooks

HarperCollinsPublishers has made every reasonable effort to ensure that any picture content and written content in this ebook has been included or removed in accordance with the contractual and technological constraints in operation at the time of publication

Source ISBN: 9780007242948

Ebook Edition © APRIL 2009 ISBN: 9780007323548

Version: 2016-10-13

From the reviews of the Martin Beck series:

‘First class’

Daily Telegraph

‘One of the most authentic, gripping and profound collections of police procedural ever accomplished’

MICHAEL CONNELLY

‘Hauntingly effective storytelling’

New York Times

‘There's just no question about it: the reigning King and Queen of mystery fiction are Maj Sjöwall and her husband Per Wahlöö’

The National Observer

‘Sjöwall/Wahlöö are the best writers of police procedural in the world’

Birmingham Post

Contents

Title Page

Copyright

Praise

Introduction

Chapter 1

Chapter 2

Chapter 3

Chapter 4

Chapter 5

Chapter 6

Chapter 7

Chapter 8

Chapter 9

Chapter 10

Chapter 11

Chapter 12

Chapter 13

Chapter 14

Chapter 15

Chapter 16

Chapter 17

Chapter 18

Chapter 19

Chapter 20

Chapter 21

Chapter 22

Chapter 23

Chapter 24

Chapter 25

Chapter 26

Chapter 27

Chapter 28

Chapter 29

Chapter 30

Keep Reading

About the Authors

Also by Maj Sjöwall and Per Wahlöö

About the Publisher

INTRODUCTION

An actual Swedish person, my college roommate Ekström, introduced me to this book. He gave me a mass-market edition on whose cover was a cheesy photograph of a raincoated man in mod sunglasses pointing a sub-machine gun into the reader’s face. This was in 1979. I was exclusively reading great literature (Shakespeare, Kafka, Goethe), and although I could forgive Ekström for not understanding what a serious person I’d become, I had zero interest in opening a book with such a lurid cover. It wasn’t until several years later, on a morning when I was sick in bed and too weak to face the likes of Faulkner or Henry James, that I happened to pick up the little paperback again. And how perfectly comforting The Laughing Policeman turned out to be! Once I’d made the acquaintance of Inspector Martin Beck, I was never again so afraid of colds (and my wife was never again so afraid of how grouchy I would be when I got one), because colds were henceforth associated with the grim, hilarious world of Swedish murder police. There were ten Martin Beck mysteries altogether, each of them readable cover-to-cover on the worst day of a sore throat. The volume I loved best and reread most often was The Laughing Policeman. Its happily cohabiting authors, Maj Sjöwall and Per Wahlöö, had wedded the satisfying simplicities of genre fiction to the tragicomic spirit of great literature. Their books combined beautiful, deft detective work with powerful pure evocations of the kind of misery that people with sore throats so crave the company of.

‘The weather was abominable,’ the authors inform us on the first page of The Laughing Policeman; and abominable it remains thereafter. The floors at police headquarters are ‘dirtied’ by men ‘irritable and clammy with sweat and rain.’ One chapter is set on a ‘repulsive Wednesday.’ Another begins: ‘Monday. Snow. Wind. Bitter cold.’ As with the weather, so with society as a whole. Sjöwall and Wahlöö’s negativity towards postwar Sweden – a theme in all ten of their books – reaches its delirious apex in The Laughing Policeman. Not only does the Swedish winter weather inevitably suck, but the Swedish journalists are inevitably sensationalist and stupid, the Swedish landladies inevitably racist and rapacious, the Swedish police administrators inevitably self-serving, the Swedish upper class inevitably decadent or vicious, the Swedish antiwar demonstrators inevitably persecuted, the Swedish ashtrays inevitably overflowing, the Swedish sex inevitably sordid or unappetizingly blatant, the Swedish streets at Christmastime inevitably nightmarish. When Detective Lennart Kollberg finally gets an evening off and pours himself a nice big glass of akvavit, you can be sure that his phone is about to ring with urgent business. Stockholm in the late sixties probably really did have more than its share of ugliness and frustrations, but the perfect ugliness and perfect frustration depicted in the novel are clearly comic exaggerations.

Needless to say, the book’s exemplary sufferer, Martin Beck, fails to see the humour. Indeed, what makes the novel so comforting to read is precisely its denial of comfort to its main character. When, on Christmas Day, his children play him a recording of ‘The Laughing Policeman’, in which the singer Charles Penrose gives out big belly laughs between the verses, Beck listens to it stone-faced while the children laugh and laugh. Beck blows his nose and sneezes, enduring an apparently incurable cold, smoking his nasty Floridas. He’s stoop-shouldered, grey-skinned, bad at chess. He has stomach ulcers, drinks too much coffee (‘in order to make his condition a little worse’), and sleeps alone on the living-room sofa (in order to avoid his nag of a wife). At no point does he brilliantly help solve the mass murder that’s committed in Chapter 2 of the book. He does achieve one valuable insight – he guesses which cold case a deceased young colleague has been reworking – but he neglects to mention this insight to anyone else, and by failing to perform a thorough search of his dead colleague’s desk he inflicts a month and a half of avoidable misery on his department. His most memorable act in the book is to prevent a crime, by removing bullets from a gun, rather than to solve one.

One striking thing about Sjöwall and Wahlöö, as mystery writers, is how honestly unsmitten they are with their main character. They let Martin Beck be a real policeman, which is to say that they resist the temptation to make him a romantic rebel, a heroic misfit, a brilliant problem-solver, an exciting drinker, a secret do-gooder, or any of the other self-flattering personae that crime writers are wont to project onto their protagonists. Beck is cautious, recessive, phlegmatic, and altogether unwriterly. By nonetheless rendering him with exacting sympathy, Sjöwall and Wahlöö are, in effect, swearing their allegiance to the realities of police work. They do occasionally indulge themselves with their secondary characters, notably Lennart Kollberg, the ‘sensualist’ and gun-hater in whose leftist tirades it’s hard not to hear the authors’ own voices and opinions. But Kollberg, tellingly, is the one detective who feels ever more estranged from the police department. Later in the series, he finally quits the force altogether, while Martin Beck dutifully persists in rising through the ranks. Although much is made (and rightly so) of Sjöwall and Wahlöö’s ambition to create a ten-volume portrait of a corrupt modern society, no less impressive is their openness to discovering, book by book, via the character of Martin Beck, how stubbornly Other the world of police work is.

As long as the mass murder remains unsolved, Beck can be nothing but miserable. He and his colleagues pursue a thousand useless leads, go door to door in freezing winds, endure abuse from fools and sadists, make punishingly long drives on wintery roads, read unimaginable reams of dull reports. To do police work is, in a word, to suffer. We readers, not being Martin Beck, can laugh at how awful the world is and with what cruel efficiency it visits pain on the detectives; we readers are having fun all along. And yet it’s the suffering cops who, in the end, produce the beautiful thing: the simultaneous solution of a very old crime and a horrific new one, a solution that turns on a delicious piece of automotive arcana, a solution foreshadowed by the words of witness after witness, ‘It’s funny you should ask …’ The Laughing Policeman is a journey through real-world ugliness toward the self-sufficient beauties of good police work. The book is fuelled by the tension between the dystopic vision of its authors and the essential optimism of its genre. When Martin Beck finally does laugh, on the final page, it’s in recognition of how unnecessary all the suffering turns out to have been. How unreal.

Jonathan Franzen

1

On the evening of 13 November it was pouring in Stockholm. Martin Beck and Kollberg sat over a game of chess in the latter's flat not far from the underground station of Skärmarbrink in the southern suburbs. Both were off duty insomuch as nothing special had happened during the last few days.

Martin Beck was bad at chess but played all the same. Kollberg had a daughter who was just over two months old. On this particular evening he was forced to baby-sit, and Martin Beck on the other hand had no wish to go home before it was absolutely necessary. The weather was abominable. Driving curtains of rain swept over the rooftops, pattering against the windows, and the streets lay almost deserted; the few people to be seen evidently had urgent reasons to be out on such a night.

Outside the American embassy on Strandvägen and along the streets leading to it, 412 policemen were struggling with about twice as many demonstrators. The police were equipped with tear-gas bombs, pistols, whips, truncheons, cars, motorcycles, shortwave radios, battery megaphones, riot dogs and hysterical horses. The demonstrators were armed with a letter and cardboard signs, which grew more and more sodden in the pelting rain. It was difficult to regard them as a homogeneous group, for the crowd comprised every possible kind of person, from thirteen-year-old schoolgirls in jeans and duffel coats and dead-serious political students to agitators and professional trouble-makers, and at least one eighty-five-year-old woman artist with a beret and a blue silk umbrella. Some strong common motive had induced them to defy both the rain and whatever else was in store. The police, on the other hand, by no means comprised the force's élite. They had been mustered from every available precinct in town, but every policeman who knew a doctor or was good at dodging had managed to escape this unpleasant assignment. There remained those who knew what they were doing and liked it, and those who were considered cocky and who were far too young and inexperienced to try and get out of it; besides, they hadn't a clue as to what they were doing or why they were doing it. The horses reared up, chewing their bits, and the police fingered their holsters and made charge after charge with their truncheons. A small girl was bearing a sign with the memorable text: DO YOUR DUTY! KEEP FUCKING AND MAKE MORE POLICE! Three thirteen-stone patrolmen flung themselves at her, tore the sign to pieces and dragged her into a squad car, where they twisted her arms and pawed her breasts. She had turned thirteen on this very day and had not yet developed any.

Altogether more than fifty persons were seized. Many were bleeding. Some were celebrities, who were not above writing to the papers or complaining on the radio and television. At the sight of them, the sergeants on duty at the local police station had a fit of the shivers and showed them the door with apologetic smiles and stiff bows. Others were less well treated during the inevitable questioning. A mounted policeman had been hit on the head by an empty bottle and someone must have thrown it.

The operation was in the charge of a high-ranking police officer trained at a military school. He was considered an expert on keeping order and he regarded with satisfaction the utter chaos he had managed to achieve.

In the apartment at Skärmarbrink, Kollberg gathered up the chessmen, jumbled them into the wooden box and shut the sliding lid with a smack. His wife had come home from her evening course and gone straight to bed.

‘You'll never learn this,’ Kollberg said plaintively.

‘They say you need a special gift for it,’ Martin Beck replied gloomily. ‘Chess sense I think it's called.’

Kollberg changed the subject.

‘I bet there's a right to-do at Strandvägen this evening,’ he said.

‘I expect so. What's it all about?’

‘They were going to hand a letter over to the ambassador,’ Kollberg said. ‘A letter. Why don't they post it?’

‘It wouldn't cause so much fuss.’

‘No, but all the same, it's so stupid it makes you ashamed.’

‘Yes,’ Martin Beck agreed.

He had put on his hat and coat and was about to go. Kollberg got up quickly.

‘I'll come with you,’ he said.

‘Whatever for?’

‘Oh, to stroll around a little.’

‘In this weather?’

‘I like rain,’ Kollberg said, climbing into his dark-blue poplin coat.

‘Isn't it enough for me to have a cold?’ Martin Beck said.

Martin Beck and Kollberg were policemen. They belonged to the homicide squad. For the moment they had nothing special to do and could, with relatively clear consciences, consider themselves free.

Downtown no policemen were to be seen in the streets. The old lady outside the central station waited in vain for a beat officer to come up to her, salute, and smilingly help her across the street. A person who had just smashed the glass of a showcase with a brick had no need to worry that the rising and falling wail from a patrol car would suddenly interrupt his doings.

The police were busy.

A week earlier the police commissioner had said in a public statement that many of the regular duties of the police would have to be neglected because they were obliged to protect the American ambassador against letters and other things from people who disliked Lyndon Johnson and the war in Vietnam.

Detective Inspector Lennart Kollberg didn't like Lyndon Johnson and the war in Vietnam either, but he did like strolling about the city when it was raining.

At eleven o'clock in the evening it was still raining and the demonstration could be regarded as broken up.

At the same time eight murders and one attempted murder were committed in Stockholm.

2

Rain, he thought, looking out of the window dejectedly. November darkness and rain, cold and pelting. A forerunner of the approaching winter. Soon it would start to snow.

Nothing in town was very attractive just now, especially not this street with its bare trees and large, shabby blocks of flats. A bleak esplanade, misdirected and wrongly planned from the outset. It led nowhere in particular and never had, it was just there, a dreary reminder of some grandiose city plan, begun long ago but never finished. There were no well-lit shop windows and no people on the pavements. Only big, leafless trees and street lamps, whose cold white light was reflected by puddles and wet car roofs.

He had trudged about so long in the rain that his hair and the legs of his trousers were sopping wet, and now he felt the moisture along his shins and right down his neck to the shoulder blades, cold and trickling.

He undid the two top buttons of his raincoat, stuck his right hand inside his jacket and fingered the butt of the pistol. It, too, felt cold and clammy.

At the touch, an involuntary shudder passed through the man in the dark-blue poplin raincoat and he tried to think of something else. For instance of the hotel balcony at Andraitz, where he had spent his holiday five months earlier. Of the heavy, motionless heat and of the bright sunshine over the quayside and the fishing boats and of the limitless, deep-blue sky above the mountain ridge on the other side of the bay.

Then he thought that it was probably raining there too at this time of year and that there was no central heating in the houses, only open fireplaces.

And that he was no longer in the same street as before and would soon be forced out into the rain again.

He heard someone behind him on the stairs and knew that it was the person who had got on outside Ahléns department store on Klarabergsgatan in the centre of the city twelve stops before.

Rain, he thought. I don't like it. In fact I hate it. I wonder when I'll be promoted. What am I doing here anyway and why aren't I at home in bed with …

And that was the last he thought.

The bus was a red doubledecker with cream-coloured top and grey roof. It was a Leyland Atlantean model, built in England, but constructed for the Swedish right-hand traffic, introduced two months before. On this particular evening it was plying on route 47 in Stockholm, between Bellmansro at Djurgården and Karlberg, and vice versa. Now it was heading north-west and approaching the terminus on Norra Stationsgatan, situated only a few yards from the city limits between Stockholm and Solna.

Solna is a suburb of Stockholm and functions as an independent municipal administrative unit, even if the boundary between the two cities can only be seen as a dotted line on the map.

It was big, this red bus; over 36 feet long and nearly 15 feet high. It weighed more than 15 tons. The headlights were on and it looked warm and cosy with its misty windows as it droned along deserted Karlbergsvägen between the lines of leafless trees. Then it turned right into Norrbackagatan and the sound of the engine was fainter on the long slope down to Norra Stationsgatan. The rain beat against the roof and windows, and the wheels flung up hissing cascades of water as it glided downward, heavily and implacably.

The hill ended where the street did. The bus was to turn at an angle of 30 degrees, on to Norra Stationsgatan, and then it had only some 300 yards left to the end of the line.

The only person to observe the vehicle at this moment was a man who stood flattened against a house wall over 150 yards farther up Norrbackagatan. He was a burglar who was about to smash a window. He noticed the bus because he wanted it out of the way and had waited for it to pass.

He saw it slow down at the corner and begin to turn left with its side lights blinking. Then it was out of sight. The rain pelted down harder than ever. The man raised his hand and smashed the pane.

What he did not see was that the turn was never completed.

The red doubledecker bus seemed to stop for a moment in the middle of the turn. Then it drove straight across the street, climbed the sidewalk and burrowed halfway through the wire fence separating Norra Stationsgatan from the desolate freight depot on the other side.

Then it pulled up.

The engine died but the headlights were still on, and so was the lighting inside.

The misty windows went on gleaming cosily in the dark and cold.

And the rain lashed against the metal roof.

The time was three minutes past eleven on the evening of 13 November, 1967.

In Stockholm.

3

Kristiansson and Kvant were radio patrol policemen in Solna.

During their not-very-eventful careers they had picked up thousands of drunks and dozens of thieves, and once they had presumably saved the life of a six-year-old girl by seizing a notorious sex maniac who was just about to assault and murder her. This had happened less than five months ago, and although it was a fluke it constituted a feat which they intended to live on for a long time.

On this particular evening they had not picked up anything at all, apart from a glass of beer each; as this was perhaps against the rules, it had better be ignored.

Just before ten thirty they got a call on the radio and drove to an address at Kapellgatan in the suburb of Huvudsta, where someone had found a lifeless figure lying on the front steps. It took them only three minutes to drive there.

Sure enough, sprawling in front of the street door lay a human being in frayed black trousers, down-at-heel shoes and a shabby pepper-and-salt overcoat. In the lit hallway inside stood an elderly woman in slippers and dressing gown. She was evidently the one who had complained. She gesticulated at them through the glass door, then opened it a few inches, stuck her arm through the crack and pointed demandingly to the motionless form.

‘A-ha, and what's all this?’ Kristiansson said.

Kvant bent down and sniffed.

‘Out cold,’ he said with deeply-felt distaste. ‘Give us a hand, Kalle.’

‘Wait a second,’ Kristiansson said.

‘Eh?’

‘Do you know this man, madam?’ Kristiansson asked more or less politely.

‘I should say I do.’

‘Where does he live?’

The woman pointed to a door three yards farther inside the hall.

‘There,’ she said. ‘He fell asleep while he was trying to unlock the door.’

‘Oh yes, he has the keys in his hand,’ Kristiansson said, scratching his head. ‘Does he live alone?’

‘Who could live with an old bastard like that?’ the lady said.

‘What are you going to do?’ Kvant asked suspiciously.

Kristiansson didn't answer. Bending down, he took the keys from the sleeper's hand. Then he jerked the drunk to his feet with a grip that denoted many years' practice, pushed open the front door with his knee and dragged the man towards the flat. The woman stood on one side and Kvant remained on the outer steps. Both watched the scene with passive disapproval.