Полная версия

Among Wolves

Marcus pushed his chair back and crossed the room to wait, glowering, in the doorway.

“Thank you,” Devin said with a little bow. “Please enjoy the rest of your meal, if you can.”

Gaspard snagged the wine bottle from his end of the table and followed Devin out the door.

They went down the passageway in silence. Devin fumbled with the key and then waited until the others preceded him into the room. When he closed the door, his hands were shaking.

“Well,” he said, turning to Marcus. “I suppose you think I handled that badly.”

“On the contrary,” Marcus replied. “I thought you handled it quite well. You left LeBeau looking very much like the ass Gaspard reported him to be.”

“I wasn’t expecting him to try to embarrass me publicly.”

Gaspard collapsed on Devin’s bunk and uncorked the wine. “He embarrassed himself. I doubt that anyone else agreed with him, Dev.”

“St. Clair seemed quite pleased with LeBeau’s opinions,” Devin pointed out. “He was glowering at me through most of the meal.”

Marcus folded his arms and leaned against the wall. “St. Clair bears watching and so does LeBeau. LeBeau accomplished what he intended to do tonight. If only one of the other passengers repeats this conversation to someone else, the rumor could spread quite quickly that your father favors education for the masses and elevating the Chronicles to Archival status.”

“I never advocated either of those things!” Devin protested.

“No, you didn’t but LeBeau made certain that those views entered the conversation. Whether you actually voiced them or not has little to do with it,” Marcus said.

“I’ll admit I find it difficult to support a system which educates a merchant’s son enough to carry on his father’s business but denies him the right to become a physician or priest unless he finds a sponsor to encourage his scholarship.”

“Apparently, Dr. Rousseau agrees with you.”

Gaspard leaned back against the window and grimaced. “Why don’t you put your stuff away?” he grumbled, pulling Devin’s knapsack out from behind him.

Devin just stared it. “I put it under the bunk when I left.”

He and Marcus grabbed for it at the same time, spreading the drawstring at the top to reveal a sheaf of folded papers.

“Your itinerary?” Marcus asked.

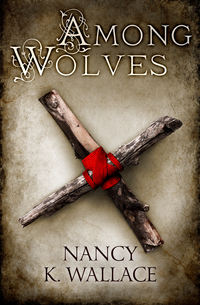

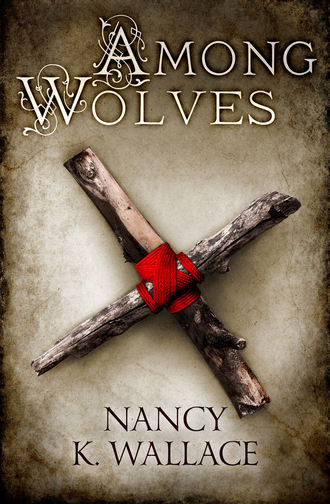

“It appears to be,” Devin replied. He unfolded it, thinking it seemed thicker than before. Something dropped to the floor from between the pages: two twigs tied with red colored thread that formed a miniature cross. He stooped to pick it up but Marcus grabbed his wrist.

“Don’t touch it,” he warned.

“Why?” Gaspard asked, bending over to see it better.

“It carries a curse,” Marcus replied.

“I’ve never heard of such a thing,” Devin said.

“You would never learn about such things in the Archives,” Marcus said, “but cursed crosses are quite common in the rural provinces. Superstition claims that the curse will come true for the first one who touches it.”

“What kind of a curse?” Devin asked.

“It depends on the color of the thread,” Marcus explained. “A blue center promises misfortune, a yellow one – illness, gray – disappointment, and red symbolizes death.”

“So, someone wants me dead?” Devin asked incredulously.

“It would seem so.” Marcus stooped to slide the offending object onto a piece of paper but it eluded him, skittering across the polished wooden floor.

“For God’s sake!” Gaspard protested, picking the thing up between his thumb and forefinger. “It’s only two twigs and some thread. What possible harm could it do?”

Devin watched with a shiver of apprehension as Gaspard unlatched the tiny window and flung it out into the sea. Whoever wished him ill, had entered his locked room and tampered once again with his belongings. The theft and return of the itinerary no longer seemed quite so trivial.

Gaspard turned from the window with a grin. “There, it’s gone. Put it out of your head, Dev. You never touched the thing so the curse can’t come true!”

“But you touched it,” Marcus pointed out darkly.

Gaspard tipped the wine bottle to his lips. “What are friends for?”

CHAPTER 6

Revelations

Gaspard chattered constantly during dinner. The clink of silverware provided a subtle counterpoint to his monologue. Despite his apparent good humor, Devin realized that the incident with the twine-wrapped cross had shaken Gaspard deeply. He simply wasn’t about to admit it to anyone.

They had no clue as to who had broken into Devin’s room. Gaspard and Marcus had entered the ship’s dining room just before Devin, and all the other passengers were present. So, it was impossible to tell who might have been responsible for placing the cross inside the itinerary. Obviously, whoever had done it, either had access to the Captain’s master key, or was a trained thief. No one they had met so far seemed a likely suspect, and Devin was tired of speculation. They’d sat for hours over the little folding table littered by fish bones piled on dirty dishes and greasy, discarded napkins. Devin and Gaspard had perched on the bunk, giving Marcus the only chair in the tiny cabin.

Gaspard lifted the wine bottle to refill Devin’s glass, but he covered it with his hand.

“I’ve had enough,” he muttered irritably, “and so have you.”

“Lighten up,” Gaspard demanded, topping off his own glass. “Why don’t we just forget about the whole thing? No one’s been hurt. It was probably just a childish prank. Someone is simply trying to scare you. If they’d intended to kill you, they could have laced the cross with poison. All you would have had to do was pick it up, and you’d be dead.”

“No, you’d be dead,” Marcus pointed out. “Devin had sense enough not to touch it when he was told not to.”

“So, I’d be dead,” Gaspard conceded. “But I’m not, so that proves my point.”

Devin grinned. “Maybe it’s a slow acting poison and tomorrow when I try to waken you…”

“Enough,” Marcus said. “This is a serious matter. That symbol represents both a warning and a threat.”

“How do you know that?” Devin asked. “I’ve never even seen one of those before.”

“My family has its roots in Sorrento,” Marcus answered. “Those curse symbols are common there. I remember my mother showing me one once. A disgruntled customer had left a blue one on someone’s stall at the market.”

“And people actually fear them?” Gaspard asked.

“Oh, yes,” Marcus said. “They are taken quite seriously. My grandmother used to tell the story of a man who was feuding with his neighbor. One morning he left a red cross in the middle of the road so that his neighbor would step on it when he took his vegetables to market. The neighbor packed up his donkey and started to town, never even seeing the cross lying in the road. The donkey stepped on it instead. That evening on the way home, the donkey tripped along the cliff road. It fell into the sea and drowned.”

Gaspard grimaced. “Shit, Dev, you owe me.”

“Apparently,” Devin agreed, his eyes on his bodyguard. “Marcus, were you raised in Sorrento?”

“No, I was born in Coreé.”

“And when did you decide to go into my father’s service?”

Marcus shrugged. “I don’t remember ever being given a choice. My family has served your family for generations both in Coreé and on your father’s estate in Bourgogne.”

“That’s hardly fair to you, is it?” Devin said.

“Your father has been good to me. Not only did he give me a responsible position in his household but he taught me to read and write.”

“He taught you himself?” Devin asked in astonishment.

Marcus nodded. “Every evening for several years.”

Devin laughed. “That surprises me. I wish I had known before.”

Gaspard savored another sip of wine. “Wasn’t he breaking the law by teaching you?”

“Gaspard,” Devin cautioned.

Marcus extended a placating hand. “It’s a legitimate question. Monsieur Roche said that my position as his bodyguard required me to carry correspondence, and it was necessary that I learn to read and write.”

“And yet, he didn’t sponsor you and send you to school which he could have done legally. He taught you himself,” Gaspard pointed out.

Marcus shrugged again. “I was already in his employ. He’s a good man. He treats his people with respect, both in Coreé and in Sorrento.”

“So, perhaps Henri LeBeau wasn’t so wrong in his assessment of Vincent Roché?” Gaspard remarked thoughtfully.

Devin glared at him. “So, you think my father was wrong to educate Marcus?”

Gaspard’s hand flew to his chest. “I didn’t say that! God, you’re touchy tonight! I am actually questioning LeBeau’s motives. I was wondering if someone had started a movement to discredit the Chancellor.”

Marcus was silent for a moment. “We had the first indications of that several months ago. Unfortunately, we suspect that your father may be one of the instigators.”

Gaspard rolled his eyes. “That’s hardly a surprise.”

“Why didn’t Father tell me?” Devin asked. The Chancellor Elite was elected by the Council. The position was normally held for a lifetime, as long as the candidate remained powerful and respected. Only twice in the past thousand years had a Chancellor been deposed by a political coup, and that had been in the early years of the empire.

“There was nothing you could have done,” Marcus replied.

“I could have stayed home.”

“And what would that have accomplished?” Marcus asked.

“My visit to the provinces wouldn’t have sparked controversy which put my father in a difficult position.”

“Well, now that your trip is underway, conduct yourself in a manner that won’t worsen the problem,” Marcus answered curtly.

“Obviously, it is already worse!” Devin said. “LeBeau is intent on starting rumors, and someone is trying hard to deter me from going.”

“But the Council’s objections and our little folk symbol seem to be at cross purposes,” Gaspard pointed out.

“What do you mean?” Devin asked.

Gaspard leaned back against the wall and drained his wine glass before answering. “It seems to me that this trip plays right into my father’s hands. Why would he try to discourage you from going, if he intends to use your visit to the provinces to discredit your father?” He fumbled for the bottle on the floor, only to find it empty.

“Maybe your father professes one view publicly and works privately to further the opposite position,” Devin said.

“Or perhaps there are two factions working independently,” Marcus suggested.

“At least, I see now why your father didn’t want you coming with me,” Devin said. “Perhaps his plan to hire tutors was just a pretense.”

“Well, I’ll be happy if I’ve helped to ruin his plan,” Gaspard said, yawning. “He can hardly use you to disgrace your father without admitting I’ve done the same to him.” He stood up unsteadily. “I’m going to bed. Why don’t you two figure this out and tell me in the morning.”

“Wait here a moment, Gaspard, while I take the dishes to the galley,” Marcus said. He turned to look at Devin. “You’d better turn in, too.”

Devin snorted. “Who can sleep? There’s far too much to think about.” He watched the door close behind Marcus, glad to see the last of the debris from dinner.

“The day after tomorrow we’ll be off this damn ship,” Gaspard reminded him. “And anyone following us will be far more obvious on land.”

“A sharp shooter doesn’t have to be close to be effective,” Devin muttered.

Gaspard shook his head. “It’s not like you to be so maudlin.”

“I’m just annoyed that a simple trip could be used as a political weapon. I wish my father had been completely honest about why he wanted me to stay home,” Devin said.

Gaspard grunted. “And would you have listened to him?”

“Maybe, if I’d known what was at stake and I’d have to watch for assassins at every turn.”

“Let me do that,” Marcus said, as he slipped back through the door. “That’s why your father sent me.”

“See you in the morning,” Gaspard said, giving him a crooked salute and stumbling out into the passageway.

“Goodnight,” Devin said, making no move to get up. He noticed the satchel in Marcus’s hand and frowned. “You’re not planning to sleep in here, are you?”

“Your father entrusted me with your life,” Marcus replied, putting his satchel on the opposite bunk. “Locks are no deterrent to this intruder, so I’m not going to leave you alone.”

“But your cabin’s just next door,” Devin pointed out.

“I’ve learned only too well that an instant can mean the difference between life and death,” Marcus replied. “Gaspard may scoff at that red cross but I take it very seriously.”

Devin took off his shirt, pulled off his boots, and lay down. He stared at the ceiling, thinking how little he really knew about the man who was sharing his room. His first memory of Marcus was the day after his seventh birthday. His father was dedicating a new park along the Dantzig. The entire family had accompanied him for the celebration. Clouds had scudded across a brilliant blue sky and sailboats dotted the broad river.

They were standing near the new fountain. His father had just finished addressing the crowd when a man suddenly darted forward, a knife in his hand. Andre, already a graduate assistant at the Académie, had grabbed Devin, shielding him with his own body. But the assassin had only targeted the Chancellor. From the protective folds of Andre’s jacket, Devin had heard a startled cry, a scuffle, and the dull thud of a body hitting the cobblestones.

Afraid for his father, Devin had pulled away in time to see Marcus pinning the attacker to the ground. The abandoned knife skittered across the pavement. His father was safe and unhurt, thanks to Marcus’s quick action. Oddly enough, after all these years, two things still troubled Devin about the incident. The first was Andre’s selfless disregard for his own safety. The other was the haunting image of a single tear running down the cheek of Marcus’s prisoner as he lay prostrate on the cobblestones.

Devin turned to look at Marcus sitting on the bunk across from him.

“The day my father was attacked in Verde Park, why did the man cry when you caught him? Was he hurt or simply frustrated that he wasn’t successful?”

Marcus stopped unpacking his belongings. On the table between them he had laid out two pistols, three knives, and a lethal looking coil of wire. He looked up at Devin.

“I wouldn’t have thought you’d remember that. You were only a baby at the time.”

“I was seven,” Devin corrected him.

Marcus closed his satchel and shoved it under the bunk. He loosened the buttons on the neck of his shirt and lay down, his hands folded behind his head.

“Your father was attacked by Emile Rousseau, a stone cutter from Sorrento. Emile had made three requests for sponsorship for his son, Phillippe. The boy was bright but not very strong physically. Emile felt he deserved to be educated. He was anxious that his son be removed from working in the stone quarries. Your father had a great many other things to deal with at the time. He had already sponsored a number of boys, and for one reason or another he postponed his decision about Emile’s son. About three months later, there was an accident at the quarry; Phillippe was crushed between two slabs when a cable broke. Emile blamed your father. He traveled for nine days on foot to reach the capital and kill him.”

Devin found it difficult to breathe. “What happened to him?” he asked.

Marcus extinguished the oil lamp on the table between them.

“He was executed,” he answered. “Now get some sleep.”

CHAPTER 7

Snow in Ombria

After breakfast, Gaspard spent the morning in the lounge dividing his time between Sophie Christophe and Josette Rousseau. For a few minutes, Devin attempted to be equally charming, but Marcus, who took his role of guardian angel very seriously, shadowed his every move, making normal conversation nearly impossible. At last, he sought the relative privacy of the deck, his bodyguard in tow.

The day had dawned clear and cold. It seemed that the Marie Lisette had left spring behind them in Coreé. The trees along the visible shoreline were still bare and leafless. To the north, clouds clustered along the horizon, blue-black and stormy.

“We’re in for a blow,” Marcus said darkly. “That storm is probably just south of Ombria now.”

“Let me guess,” Devin teased, “your grandmother was a sailor, too.”

Marcus didn’t crack a smile. “Sorrento is landlocked,” he retorted. “But, it doesn’t take a sailor to recognize bad weather. I don’t imagine we’ll get much sleep tonight.”

Devin didn’t comment. He wondered if Marcus was aware that he had lain awake most of last night. Every footstep in the passageway had set his heart thumping. He’d always felt safe in Coreé. It wasn’t as though he hadn’t realized, especially after the incident at Verde Park, that his family would live under constant threat. But that threat had only touched him once, personally. His childhood had remained remarkably charmed and unblemished despite his father’s elevated position.

He leaned forward on the rail and watched the churning water as it rushed by the prow.

“Had it occurred to you that Dr. Rousseau might be related to Emile?” he asked, after a moment.

“Dr. Rousseau lives in Treves. His family has resided there for several generations,” Marcus responded.

“He told you that?”

“No, the Captain did. I made it clear that, for security purposes, it was imperative I know more than just the obvious things about the others on board. Besides, any good Captain makes a practice of knowing his passengers, especially, when he is entrusted with carrying the son of the Chancellor Elite.”

Devin rolled his eyes. He seemed doomed to drag his father’s title along with him, like an anchor around his neck. “Do you trust Captain Torrance?”

“Your father booked your passage. He wouldn’t have chosen this particular ship had he any qualms about Captain Torrance’s loyalty or his skill.”

Devin shrugged. He wished he could recapture yesterday’s thrill of excitement. Today, he felt jumpy and suspicious. He envied Gaspard’s carefree attitude. But now that he knew about both the political turmoil in Coreé and its potential threat to his father, they weighed on him. He thought again about his father’s abrupt reversal, the evening before he left, in allowing him to continue with his trip. Had his father wanted Devin out of the city for his own safety? Did he hope that, in fifteen months, the threat of revolution might have been averted or resolved? For the first time Devin truly considered booking his passage back to Coreé when they docked in Pireé.

The wind drove them below deck by afternoon and true to Marcus’s prediction the storm hit by nightfall. The choppy water sent half the passengers, including Gaspard, to their cabins. Dr. Rousseau was kept busy tending seasick travelers for most of the evening. Devin had to admit that the heaving floors made him feel a little uneasy himself, but Marcus seemed completely unaffected.

Devin hadn’t seen Henri LeBeau all day and was surprised when he came into the lounge after dinner. He crossed the floor and headed immediately to where Josette and Devin were seated talking in the corner of the room. Marcus detached himself from the wall and assumed a protective stance next to Devin. The room fell into expectant silence around them.

LeBeau sketched a small bow. “I wondered if I might have a word with you, Monsieur Roché.”

“By all means,” Devin said. “What’s on your mind?”

“Could I speak with you alone?” LeBeau asked.

“That’s not possible,” Marcus replied grimly.

Josette rose to her feet and smiled at Devin. “Forgive me, monsieur, but I should be going.”

Devin stood up, hoping to detain her. “Please stay a little longer. I’m certain this will only take a moment.”

She lowered her lashes and shook her head. “I’ll try to come back later, monsieur, if I can. I need to check with my father and see if there is anything I can do to help him.”

Devin watched her go with regret. With Gaspard sick in his cabin, he’d been free of any competition for Josette’s attention. Tomorrow, she would continue on with the Marie Lisette and he would begin his journey overland across Ombria. He turned in annoyance to LeBeau.

“What is it that you wanted?”

LeBeau cleared his throat. “I’d like to apologize. I drank too much wine before dinner last night. I’m afraid it tends to make me argumentative. I fear I spoiled everyone’s meal. I’m sorry.”

Devin raised his eyebrows. “Surely your political views haven’t changed overnight?”

“Of course, they haven’t,” LeBeau assured him. “But the dinner table was not the place to discuss them.”

Devin inclined his head. “On that we agree.”

“I hope you can forgive me,” LeBeau continued. “I have the utmost respect for both your brother and your father. I regret that you may have found my remarks offensive.”

It was as though Devin could hear his father’s voice in his mind: Never decline an apology that is proffered publicly. If you do, you allow your opponent to become the injured party.

“We all speak without thinking sometimes,” he remarked lightly. “This trip is almost over. Let’s put last night’s discussion behind us.”

“Thank you,” LeBeau said with relief. “My invitation still stands. In spite of everything, I would still like to show you Treves.”

“I’m sorry but our plans are not definite,” Devin answered diplomatically. “I have no idea when we will arrive in Arcadia, so it is impossible to commit to anything.”

LeBeau retrieved an envelope from the inside pocket of his jacket. “I’ve written down my address for you with directions to my summer home, just south of the city. I’d consider it a favor if you’d take the time to stop for a visit.”

When hell freezes over, Devin thought. “Thank you,” he replied, making a production of putting the envelope in his own pocket. “If we cannot take time to visit you, at least I am certain I will see you at the Académie next year.”

LeBeau laid a hand on his arm. “I hope to see you before that.”

Devin resisted the urge to shake off the offending hand, and smiled graciously. “Good night,” he murmured.

LeBeau answered only with a bow. He turned and was gone. Bertrand St. Clair followed discreetly on his heels.

Conversation started again as quickly as it had stopped and Marcus glanced at Devin.

“That was well done,” he said under his breath.

Devin shrugged. “My father would say it is bad form to call a man a liar in public but I was truly tempted.”

The rough night made sleep nearly impossible as the ship tossed uneasily on stormy waters. Both Devin and Marcus were up and dressed before dawn. Up on the forecastle, they discovered a light coating of snow covering the deck. The rigging hung thick with ice. Every movement of the ropes or sails sent glass-like shards smashing onto the deck. Stray flurries still floated down from a leaden sky.

They sailed into a harbor made ghostly with frosted spars and shrouds of mist, docking just as the sun struggled feebly to lighten the skies. They had said their goodbyes to the other passengers last night Devin had received an invitation from Dr. Rousseau to visit his home when he reached Treves. And Gustave Christophe was anxious that he stop in Tarente to meet the boy who swept his shop.

Only Henri LeBeau and Bertrand St. Clair also planned to disembark at Pireé but they had yet to appear on deck when Devin, Gaspard, and Marcus left the ship. Devin’s first steps off the gangplank were awkward and halting. His legs had grown used to the roll of the ship, and solid ground felt surprisingly odd in comparison.

The port of Pireé seemed strange and exotic. The first thing Devin noticed were the large signboards hanging in front of every shop. Instead of words, each bore a painted or carved likeness of the merchandise that was sold inside. The bright and unsophisticated images made him feel as though he had landed in some foreign port where he didn’t speak the language.