Полная версия

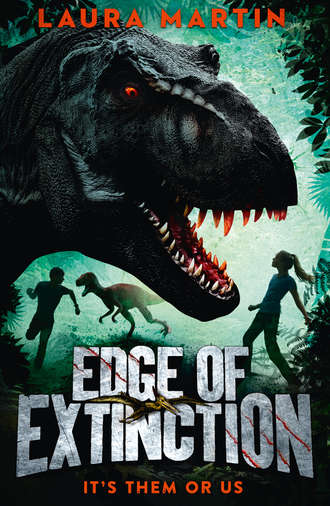

Edge of Extinction

Copyright

First published in Great Britain by HarperCollins Children’s Books in 2016

HarperCollins Children’s Books is a division of HarperCollinsPublishers Ltd,

HarperCollins Publishers

1 London Bridge Street

London SE1 9GF

The HarperCollins Children’s Books website address is

www.harpercollins.co.uk

EDGE OF EXTINCTION

Text copyright © Laura Martin 2016

Cover illustration © Fred Gambino

Cover design © HarperCollins Publishers 2016

Laura Martin asserts the moral right to be identified as the author of this work.

A catalogue copy of this book is available from the British Library.

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the non-exclusive, non-transferable right to access and read the text of this e-book on screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, down-loaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins.

Source ISBN: 9780008152895

Ebook Edition © 2016 ISBN: 9780008152901

Version: 2016-04-13

For all the kids with their nose in a book.

You are my favourite kind of dreamer.

Contents

Cover

Title Page

Copyright

Dedication

Chapter 1

Chapter 2

Chapter 3

Chapter 4

Chapter 5

Chapter 6

Chapter 7

Chapter 8

Chapter 9

Chapter 10

Chapter 11

Chapter 12

Chapter 13

Chapter 14

Chapter 15

Chapter 16

Chapter 17

Chapter 18

Chapter 19

Chapter 20

Chapter 21

Chapter 22

Chapter 23

Chapter 24

Chapter 25

Coming soon

About the Publisher

I needed two minutes. Just enough time to get to the maildrop and back, but I had to time it perfectly. Dying wasn’t an option today, just like it hadn’t been an option the last ten times I’d done this. I’d thought it would get easier after the first time. It hadn’t.

I gritted my teeth and scanned the holoscreen again. The mail was due to arrive in less than a minute, and although the forest above me looked harmless, I knew better. The shadows between the trees were too silent, too watchful. I hit the refresh button. The drill was simple – refresh the screen, scan for a full minute, refresh again and scan the opposite direction. I imagined it was similar to what parents used to teach their kids about crossing the street, back when there were still streets to cross and cars to drive on them.

The thumping whirr of the plane crackled out of the holoscreen’s speakers and I glanced at my watch. 6:59 a.m. Right on time. My nerves tingled with a dizzying mix of excitement and terror as I watched the small black aeroplane come into view on the holoscreen. It whipped the surrounding forest into a frenzy as it glided just above tree level. I bounced on the balls of my feet, rolling my head back and forth to stretch out my neck as I gave myself a mental pep talk. Be smart. Be aware. Be fast, I commanded myself. Every second counted. A small hatch at the bottom of the plane opened and a large bundle fell the remaining thirty feet to the maildrop’s landing pad. The plane quickly regained altitude and zipped away over the trees towards the other side of the compound, where it would pick up the outgoing mail.

With one last look to confirm the coast was clear, I clambered up the ladder, unlatched the thick metal plate that served as the compound’s entrance, and launched myself from the hatch. It was like entering another world. After the silence of the tunnel, the buzz of insects was almost deafening. My feet dug into soft, damp earth as I ran, and the humidity made the air heavy in my lungs. I felt alive. I felt exposed.

The maildrop was located one hundred yards to my left and I reached it just as the lid was starting to close. The maildrops had been designed back when our founding fathers had believed that the human race would be able to live at least part of their lives topside. They’d been wrong. The drops had all been re-engineered over fifty years ago so that no one had to risk their life venturing aboveground. But there was a thirty-second delay before the mail shot underground to be sorted and searched. Thirty seconds was all that I needed.

There were at least forty packages and letters, and I pawed through them looking for the marines’ official seal. My breath caught in my throat when I finally spotted a large bundle with the black circle and golden ark on the side. Jackpot. I grabbed the package by each end and ripped it right down the middle, hoping the marines would think it had broken open when the plane dropped it. Inside I found a jumble of uniforms, regulation grey socks and port-screen batteries. I was starting to worry that this whole trip was going to be a bust when I saw the small black box. I scooped it up, feeling an almost painful surge of hope in my chest.

The tiny devices were used to pass information and messages between the compounds. This one’s rubberised case was roughly the size of a deck of cards and was made to protect the data plugs on the inside from the jarring airdrop. I was already pushing it on time, but I jerked the scan plug out of my pocket and jammed it into the side of the box anyway. Maybe this time the box would have something.

Five seconds later, I’d downloaded everything the information box could tell me. Pulling out my plug, I wiped the box on my grey uniform to remove any traces of my fingerprints before pushing it back inside the half-open package. In a community where resources meant the difference between life and death, theft was not tolerated. Although, I reasoned, I hadn’t really stolen the information. I’d just made a copy of it. Still, if the marines even suspected the information box had been breached, there would be an investigation. I double-checked the package to make sure I’d left no trace of my tampering. My double-checking nearly cost me my hands, but I managed to yank them out before the steel lid of the drop clicked shut. Seconds later the packages plummeted down the three storeys to the mailroom below.

I heard the sound of a tree branch snap and I jerked my head up, scanning the surrounding trees. My feeling of elated hope from just moments before fizzled in my chest, replaced with a cold familiar knot of fear. I’d been above for only a minute, but that was more than enough time for them to get my scent. I’d taken too long at the maildrop. Double-checking the package had been a stupid mistake. And my survival depended on not making stupid mistakes.

Turning on my heel, I sprinted for the compound entrance. I spotted the disturbance to my left when I was still fifty yards from safety. The ground began to tremble under my feet, and I willed myself not to panic. Panicking could happen later, when I was safely underground with two feet of concrete above my head.

I spotted the first one out of the corner of my eye as it burst from the trees. Blood-red scales winked in the dawn light as its opaque eyes focussed on me. It was just over ten feet and moved with the quick, sharp movements of a striking snake.

My stomach lurched sickeningly as I recognised the sharp, arrow-shaped head, powerful hindquarters and massive back claw of this particular dinosaur. It was a deinonychus. Those monsters hunted in packs. Sure enough, I heard a screech to my left, but I didn’t bother to look. Looking took time I didn’t have. I hit the twenty-yard mark with my heart trying to claw its way up my throat. The deinonychus was gaining on me.

Fifteen yards.

Ten yards.

Five.

Two.

Like a baseball player sliding into home base, I dropped neatly down the compound hatch and locked it in one practised movement before plummeting the remaining few feet to the floor. Two seconds later, too close for comfort, I heard its claws tear at the metal lid. A heartbeat after that, the rest of its hunting mates joined it in an attempt to flush me out of my hole. I was lucky I was fast, but then again, you didn’t last long topside if you weren’t.

I leaned over the small holoscreen monitor on the wall and typed in the anonymous user code my best friend, Shawn, had shown me when I was seven. Almost five years later and it still worked. The screen beeped and chirped happily at me, completely at odds with the crunching, scratching and mewling screams coming from five feet above.

The creatures would dig around the concrete-enforced entrance for another ten minutes or so before they moved on, and I didn’t want anyone else to run into them. Not that many people ventured topside besides me. It wasn’t exactly legal. The compound marines would be furious if they knew that an eleven-year-old girl had dared to stick her head above the ground. I bit my lip and typed in the message that would be delivered across North Compound. “Pack of deinonychus at entrance C. 7:01 a.m. – Anonymous User.” I had my own code, but there would be too many questions if I used it. Questions I had no intention of answering.

I glanced up at the only security camera in this tunnel. It had been disabled for exactly two days and eleven hours. They weren’t as hard to break as you’d think. The fact that it was still broken was a little amazing, though. I’d thought I’d have to break it again this morning. Compound security must be slipping with all of the extra manpower they’d been throwing at tunnel reinforcements.

I sank down against the wall and took a deep breath, readjusting my lungs to the filtered, weightless air of the compound. I always felt like my senses were somehow dulled and muted after surviving a trip topside. Things down here just weren’t as bright, smells weren’t as strong, and sounds weren’t as crisp. Not that I could really complain. The topside world was amazing, but the compound had one thing going for it the topside world never could. It was safe.

I pulled the scan plug out of my pocket and stared at it for a second, wondering what information I’d managed to copy this time. It was probably nothing, I warned myself. Just the same old messages about supply drops and regulation enforcements. But a stubbornly hopeful part of me couldn’t help but think that maybe, just maybe, this time it would have information on it about my dad. I tucked the plug into my bag, careful to conceal it inside the lining. I would hide it properly later, but this would have to do for now. Getting the information almost made up for the fact that I was going to be late to class. Again. But at that moment, after almost becoming a dinosaur’s breakfast, I couldn’t make myself care.

Deciding that I was going to be late no matter what I did, I reached in my pack and pulled out my journal. Its leather cover was soft and familiar under my hands as I opened it to the entry I’d made about Deinonychus. I looked at my rough sketch of the dinosaur that still screeched above me and shook my head in disgust. The dusty volume I’d found on this particular dinosaur had apparently been riddled with errors. For one, that back claw was way longer than I had drawn it, and I’d had no idea just how fast they really were. I quickly sketched in the claw and added in the few facts I’d been able to gather while running for my life. Satisfied, I put it away to work on at another time. Even though the camera in this tunnel was disabled, it made me nervous having my journal out in the open. It wasn’t exactly legal either.

As I shut my pack, I realised that my hands were still trembling and I flexed my fingers in irritation. I was safe, but my hammering heart and tingling nerves hadn’t got the message yet. Nothing like a good dinosaur attack to wake you up in the morning, I thought wryly.

My dad used to tell me stories about life before the dinosaurs, before the Ark Plan had been enacted, but it was hard to believe them. I couldn’t imagine a world where people lived with all that sun and sky and freedom, three things sadly lacking in North Compound. I glanced up and felt a reluctant gratitude for the thick concrete above my head. Without it, the human race wouldn’t exist. And I guess when you thought of it that way, sun, sky and freedom weren’t that high a price to pay.

The holoscreen beside me chirped, and I squinted at it. Someone had responded to my alert. It flashed twice and then a message scrolled across the screen. “Sector 24 reinforcements postponed due to deinonychus report. Reminder – no resident in North Compound is authorised to have an anonymous account.” I rolled my eyes. Our government’s quest to abolish the anonymous accounts had failed time and time again. But I was glad to see that tunnel reinforcements had been moved. The compound’s marines occasionally had to go topside to check that the reinforcements were being installed properly, and even with their stun guns, it was often deadly. My anonymous account had potentially saved someone from getting eaten today.

One of the deinonychus’s claws screeched across the metal hatch that separated their world from mine, forcing me to clap my hands over my ears. The creatures were still scrabbling and roaring, furious at their lost meal. And I wished, for the millionth time, that I could feed them the idiot scientists who had brought them out of extinction in the first place. Although being ripped to pieces might be too kind for the people who had almost wiped out the entire human race.

I needed to get away from the compound entrance before someone came to investigate my report. As I got to my feet, I eyed my reflection in the glossy surface of the holoscreen. Sweat dripped down my face, my grey eyes looked a bit wild and my curly red hair had broken free from its ponytail. As I battled to get it back under control, I remembered my dad standing behind me, a look of pure bafflement on his face as he tried to force my hair into some sort of order. At times like that, I think both of us had thought about my mum and how, if she hadn’t died giving birth to me, it probably would have been her teaching me about hairstyles. He’d actually got pretty good at it before he’d disappeared, but I’d never developed the knack. Now I scraped it back into its ponytail. It would have to do. I set out at a jog.

The floor of the tunnel slanted downwards as I wound my way through the cement maze that made up North Compound. Of the four compounds in the United States, North was the smallest. Sometimes I loved that, but most of the time I didn’t. It meant that I knew everyone in the compound and everyone knew me. Which would be fine, if everyone also didn’t hate me.

I’d played around with the idea of asking for a voluntary transfer to East Compound or West Compound, but I’d never been able to bring myself to do it. The clues to my dad’s disappearance were here. So here was where I had to stay. I turned a corner and ran past countless doors embedded in the tunnel wall but ignored them. They were empty by now anyway – everyone needed to report to work by seven fifteen sharp if they wanted to avoid a late penalty. That thought had me picking up my pace. Goose bumps broke out on my arms as the temperature dropped the further down into the compound I went, the walls alternating between the smooth concrete of man and the rough rock of nature.

The North Compound, like the other three compounds, had originally been built as a bunker in case of nuclear decimation or something like that. Almost two hundred years ago, engineers had sat around discussing how to turn an abandoned rock quarry into an underground city where people could survive for months or even years. They had no way of knowing that what they built would protect the human race, not from nuclear fallout but from animals that had been extinct for thousands of years. I wondered if they would have designed things differently if they’d known.

Five minutes later I was out of the habitation sector and entering the main labyrinth. Here the tunnels bustled with activity as men and women, wearing the same faded grey as myself, hurried off to their various occupations. I weaved my way through the crowd, avoiding eye contact. Five years had taken the edge off most of the residents’ general dislike for me but hadn’t dulled it completely. I did my best to stay off their radar, and in return they didn’t go out of their way to give me dirty looks. It wasn’t a foolproof system, but it worked.

I made it through the crowd and jogged down the side tunnel towards the school sector and my homeroom. Right before I rounded the last turn, a muffled sob brought me to a halt. Not again. I groaned as I backtracked down the tunnel. Stopping outside the third storage door, I lifted the latch and flicked on the light.

Shamus was sitting in the corner of the small stone room, wedged between two stacks of broken desks, just like I knew he would be. His big blue eyes blinked up at me, and I sighed. Shamus Clark was five and, like me, a social outcast. His father was the allotment manager, the most hated job in the NC. No one liked to be told that their food ration had been cut. Unfortunately, the other kindergarteners in Shamus’s class had inherited their parents’ prejudices. I knew how that felt all too well.

“Toby again?” I asked, wiping a tear off his chubby cheek with my thumb.

Shamus nodded, scrubbing at his snotty nose with his sleeve. “He … he pushed me down, and he took my lunch ticket. I scraped my knee. See!” Tears momentarily forgotten, he proudly showed me a small scrape.

Lunch tickets were given out to each family as part of their weekly allotment and were the first thing taken away if a job was shirked or done poorly. Knowing your child would go hungry was enough to keep people reporting to work every day. It was a harsh system, but it was fair. Although that could be said about every aspect of compound life. I frowned. No matter how good the system was, it hadn’t prevented Shamus from being bullied. Toby’s parents didn’t seem to care that Toby stole Shamus’s lunch tickets because they failed to provide them for him.

“You are going to have to start standing up for yourself,” I explained gently, pulling Shamus to his feet and brushing dirt off his uniform. He wiped his eyes and looked unconvinced. “You know he only takes it because he’s hungry, right?” I sighed. “Let’s go. We need to get you to class.” Shamus trudged along beside me, his hot little hand grasping mine, and I felt a flash of guilt. If I’d got eaten this morning, who would have found Shamus in the broom closet?

I knocked on the door of Schoolroom A, and the kindergarten teacher, Mrs Shapiro, answered looking annoyed. With a wide smile I didn’t really mean, I ushered Shamus into the room.

“I’m sorry he’s late. It’s completely my fault.”

Mrs Shapiro huffed in exasperation, slamming the door in my face. Lovely.

Two minutes later, I slid through my classroom door and to my desk in one seamless motion, keeping my eyes down in the hopes that Professor Lloyd wouldn’t see me if I couldn’t see him. Slipping my port out of my backpack, I laid it on my desk and finally looked up. Luckily, his back was to me as he scrawled out an agenda on the board.

“Not bad,” quipped a familiar voice at my elbow. I flicked my eyes up to see Shawn Reilly grinning at me from across the aisle. I rolled my eyes and bit back a smile.

“Shamus,” I mouthed in explanation as I turned on my port. Its screen flashed blue and then green.

Shawn held up three fingers, wordlessly asking if it was the third time in the last few weeks that I’d had to help out Shamus.

I shook my head and held up four. He nodded. The PA system hissed and crackled, and we all fell silent as we waited for the day’s announcements.

“Good morning,” barked the voice of our head marine, First General Ron Kennedy. I wrinkled my nose in dislike. Each compound had ten marines stationed to keep the peace and assist in brief forays topside for things like tunnel reinforcements. They were the Noah’s eyes and ears at each of the compounds, reporting back problems that arose. Of those ten, General Kennedy was my least favourite. “Today is Monday, September 1. Day number 54,351 here in North Compound.” Kennedy went on. “Please rise for the pledge.” As one, the class rose and turned to face the black flag with the Noah’s symbol of a golden boat positioned in the corner of the classroom.

“We pledge obedience to the cause,” the class chanted in unison, “of the survival of the human race. And we give thanks for our Noah, who saved us from extinction. One people, underground, indivisible, with equality and life for all.” We took our seats.

“Tunnel repairs are continuing,” General Kennedy’s voice went on, “so please avoid using the southern tunnels in sections twenty-nine to thirty-four unless absolutely necessary. Mail was delivered today,” he said, and then he paused as though he could hear the excited murmur that had greeted this news. Mail was delivered only four times a year between compounds, and sometimes less than that due to the danger of sharing the skies with the flying dinosaurs. Although I was pretty sure the ones that flew and swam weren’t technically considered dinosaurs. I remembered a science lesson where we’d learned they were really just flying and swimming reptiles, but I didn’t see what the difference was.

“As always, the mail will be searched and sorted before being delivered. We appreciate your patience as we work to ensure the safety of all citizens here in North.”

When I glanced up, Shawn was studying me suspiciously, his brow furrowed over dark blue eyes.

I tried to keep my face blank, like the mail being delivered and my being late had absolutely nothing to do with each other. But I was a horrible liar.

“It wasn’t just Shamus, was it?” Shawn hissed, pointing an accusing finger at me. “You were checking the maildrop again.”

“Shhhh,” I hissed back, as General Kennedy went on to discuss the upcoming compound-wide assembly scheduled for later this week.

“You are going to get killed,” Shawn frowned. “And all for some stupid hunch.”

“I won’t.” I huffed into my still-wet fringe in exasperation, wishing that I’d chosen a best friend who wasn’t so nosey. “And it isn’t a hunch.”

Shawn raised an eyebrow at me. “OK,” I conceded. “It’s a hunch.” But just because year after year there’d been no mention of the disappearance of the compound’s lead scientist didn’t mean there never would be, I thought stubbornly. How could I explain to Shawn the pull I felt to find out what had happened to my dad? I imagined it was similar to what it felt like to lose a limb, a constant nagging sense of something missing, a dull ache that wouldn’t go away.