Полная версия

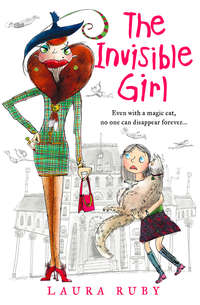

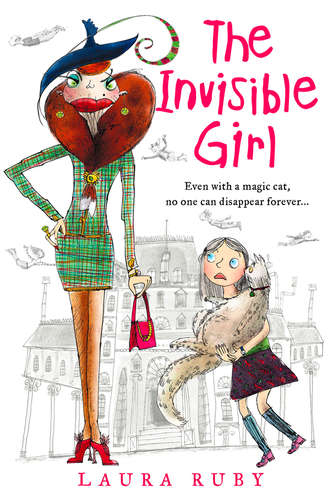

The Invisible Girl

Gurl sat up in bed, clutching her chest. A dream. But not all of it. Not Luigi’s chocolate cake, which she could still smell on her fingertips. Not the cat, who slept across her feet under the threadbare blanket. But what about the rest?

She looked at her hands. They were thin and pale, but they were there, plainly visible. Gurl pulled the covers off her legs. Hands, check. Legs, check. She pulled the covers back up and shivered. The clock on the wall read 5.36am and pinkish sunlight marbled the iron sky outside the windows. The alley had been so much darker. Maybe that was why her hands had looked so strange, why the waiter hadn’t seen her. She had been hidden in dark shadows, odd shadows that mottled her skin.

Yes, she thought. That had to be it.

The cat mewled softly from beneath the blankets and crawled up to sit at Gurl’s side. She wasn’t much to look at. Cats in books had impish black faces and blue eyes, or smushed noses and fur the colour of butterscotch. With a wide, plain face and fur the grey of morning fog, this cat seemed unremarkable in comparison. Except for her eyes, the acid-green eyes that blinked so slowly as Gurl scratched one ear, then the other. The cat rolled over and exposed a white, tufted belly. She put her forepaws in the air and flexed them, clutching at something only she could see.

Gurl scratched the cat’s belly and a strange feeling came over her, a sleepiness, a peacefulness. A musical sort of purring filled Gurl’s ears, erasing the frown that had pulled at her lips. If a tree falls in the forest and there is nobody around, she thought, does it make a sound? If a tree falls…if a tree falls…if a tree falls…

If anyone in the dorm had awakened, they would have thought Gurl had gone into a trance. Time passed, syrup slow, as Gurl scratched and scratched and scratched. Finally, the cat turned her little face to the clock and mewled softly. Gurl shook herself awake and checked the time: 5.57! In three minutes the alarm would ring and all the kids would wake up. What was she going to do with the cat? She couldn’t let anyone see it or else they would take it. Gurl was not very brave, not as brave as she wanted to be, but she was responsible. And if the cat had really chosen her, well then, the cat was Gurl’s responsibility.

Gurl climbed from her bed and pulled a box from underneath it, a box with a couple of old sweaters in the bottom. She reached into her bed, lifted the sleepy animal and laid it gently in the box. The cat peered at Gurl. “I’m sorry,” whispered Gurl, “but I can’t let anyone see you. Can you stay in this box until I can come back?”

The cat circled the box, kneading the sweaters. After curling up in a ball, she reached out with a white paw and rested it on top of Gurl’s hand. “You understand, don’t you?” Gurl breathed. Gurl knew that was a silly thing to think, that the cat was just an animal and couldn’t possibly understand what Gurl was saying. But cats were rare and special, Gurl told herself. Maybe the cat did understand. Gurl gave the cat one last pat and then she closed the box again, hoping that cats liked small spaces and sleeping for hours.

She didn’t have a lot of time to worry about it because soon the alarm rang and the kids climbed from their beds. As usual, no one greeted Gurl, no one asked her if she wanted to sit with them at breakfast. She ate as she always did, in the very back corner of the cafeteria, watching as all the others laughed and talked and shoved one another. It was just as well. Gurl had nothing to say to them anyway. A piece of toast fell lard-side down in front of her, but she ignored it.

“What’s up, Leadfoot?” said a voice. Gurl didn’t have to look to know who it was: Digger.

“Nothing,” Gurl muttered. It was what she always said.

“What? I can’t hear you!” Digger bellowed, getting up from her own table to lumber over to Gurl’s. She was huge, bigger than most of the boys even, with a great square head like a block of wood. She wasn’t much of a flyer, but she didn’t need to be. Once a brick had come loose from the second storey of the dormitory building. It had fallen on Digger’s foot while she was playing killer ball in the yard. She’d turned and proceeded to kick the wall so hard that some of the other bricks came loose. “Nobody messes with me,” she said. “Not even the buildings.”

Digger was tough, the toughest actually. The only thing that wasn’t tough was the way she picked her nose: delicately, with the tip of her pinky extended like she was sipping tea from fine china.

Gurl pushed her eggs around her plate, wondering if Digger would flip them on the floor or in her lap. Not that it mattered, for the eggs smelled like sweaty socks stuffed with day-old fish and were the last things in the world Gurl wanted to eat.

Digger snatched the fork from her hand and smacked Gurl’s plate to the floor, the eggs pellets scattering. “I said, I can’t hear you! Speak, Freak!”

Gurl finally looked up into that big blockhead face. Digger’s expression was the same as the waiter’s had been: smug and triumphant. It was like she knew that Gurl was beaten already, doomed before she began. Gurl thought of what she had done to the waiter, and a tiny smile made her lips curl up at the corners.

Digger’s nostrils flared. “Look at you,” she said. “You’re pathetic. All you do is sit there like a lump and stare at everyone.” With her knuckles, Digger rapped painfully on Gurl’s skull. “Hello, Lump. Is anyone in there?”

For a moment, Gurl wished she could disappear. Wouldn’t that be amazing? Then what would Digger do?

But her hands and legs and the rest of her stayed exactly the way they were and even Digger grew bored. “Freak,” she muttered and went to find someone more interesting to torment.

A word about Hope House: there are places in the world where so many desperate people have lived and so many bad things have happened that the places themselves have become desperately bad. They’re damp and weird and smell like foot fungus. The windows are never clean and the lino curls up at the edges because it can’t stand the floor. Every corner is sprayed with cobwebs and quivering shadows. When you walk into these bad places, you can feel a headache brewing between your eyebrows, a churning in your gut, a cold prickle at the back of your neck. You feel sad and angry and helpless, all at the same time. These bad places seem to hate you, but they also seem to want to keep you there very, very much.

Hope House for the Homeless and Hopeless was one of these places. But, as Gurl had learned in her history lessons, Hope House for the Homeless and Hopeless had not always been called Hope House for the Homeless and Hopeless. Back in the early 1800s, when it was first built, it was called The Asylum For The Poor, The Lazy and The Wretched, and its mission was “to teach idle, wild and disobedient children self-discipline of the body and soul”. After that the name was changed again, to The Home of the Friendless—“for unprotected children whose only crime is poverty”. And then for a while it was called The Institute of the Destitute, which offered orphans job training in such occupations as sheep shearing, basket weaving and flower arranging.

Despite the various name changes, the mission was generally the same: keep homeless kids out of trouble and try to teach them something useful. To that end, in literature class the orphans of Hope House were again composing business letters to rich people urging them to join the Hope House “Adopt-an-Orphan” programme, in which a donation of just $7.50 a day—only the price of a double latte!—would keep an orphan fed for a year. In art they made Hope House oven gloves and place mats, which were sold for $14.95 plus $5.99 shipping and handling on the orphanage website. In computer class they learned how to send emails to thousands of people at a time, with subject lines like “Don’t let hope die at Hope House!” or “The truest heart gives until it hurts!”

As always, Gurl finished her work quickly and then stared out of the window or watched the other students. Preoccupied by the fact that she might have disappeared like a phantom the night before, and by the cat that she hoped was still sleeping in a box underneath her bed, she didn’t notice the new boy until biology. Gurl was particularly bored in biology because they never learned about any animals except birds (with the occasional bat or flying squirrel thrown in). And while Gurl liked birds well enough, she hated it that everyone else worshipped them just because they could fly. Just once Gurl wanted to learn about a wolf or a salmon or a salamander or an ant. “An ant can lift ten times its own body weight,” Gurl had once timidly told her teacher, Miss Dimwiddie, hoping that maybe she might do a lesson on something else. Miss Dimwiddie had barked, “Birds eat ants for lunch.”

This morning Miss Dimwiddie began with the same question she always began with: “Who wants to tell me about the bumblebees?”

“Bumblebees!” echoed Fagin, Miss Dimwiddie’s parrot, who perched on Miss Dimwiddie’s shoulder.

Persnickety’s hand shot into the air. Since it was the only hand to shoot into the air, Miss Dimwiddie said, “Yes, Persnickety.”

“Bumblebees shouldn’t be able to fly,” Persnickety said, knotting her hands on the top of her desk. “Their bodies are too big and their wings are too small.”

“Yes, Persnickety, that’s absolutely right.”

“Absolutely right,” croaked Fagin.

“Now, children, I want you all to remember that. Bumblebees look as if they’d be too heavy to fly and yet scientists have discovered that they beat their wings in circles to create lift. Now, none of you look like you can fly either, but you must all be like the bee. You children can use the bumblebee to inspire you to great heights. All right?”

She smiled, waiting for the students to agree, but the room was silent. Miss Dimwiddie cleared her throat. “Well then. Today we’re going to talk about the blue-footed booby.”

“Blue-footed booby,” parroted Fagin.

The class sniggered and Miss Dimwiddie put her hands on her ample hips. “Does someone want to tell me what’s so funny?” Ruckus, always the first to cause a ruckus, shouted, “You said ‘booby’.”

“You’re the booby,” said Fagin.

Ruckus’s tiny black braids, sticking up from his head like caterpillars reaching for a leaf, shook. “Shut up, you dumb bird.”

Fagin flapped his wings. “Booby head. Worm head.”

Miss Dimwiddie continued as if she hadn’t heard. “I want you all to turn to page eighty-nine in your textbooks. You will see a photograph of the blue-footed booby. Note its distinctive powder-blue feet.”

“Powder-blue feet,” Fagin crowed.

“The blue-footed booby lives on the Galapagos Islands,” said Miss Dimwiddie. “The blue feet play an important part in their mating rituals.” Again she had to ignore a lot of snickering. “The male booby initiates the mating dance by raising one foot and then the other. Like this…” Miss Dimwiddie raised one foot then the other, delicately pointing her toes as they touched the ground. On her shoulder, Fagin did the same.

“See?” said Miss Dimwiddie. “Blue foot, blue foot. Blue foot, blue foot.”

The class bit their knuckles to stifle their laughter. Except for one person, who laughed out loud. Gurl turned to look. In the back of the room was a new boy that Gurl hadn’t noticed before. This was unusual, the not noticing, and because of it Gurl watched him all the more closely. He was broad-cheeked and broad-shouldered, with large, wide-set blue eyes that made him look a bit like a praying mantis. He noticed Gurl noticing him and he raised his eyebrows. She looked away, feeling her face grow hot. (She hated to be noticed noticing.)

Miss Dimwiddie stopped blue-footing about. “That’s enough!” she said sternly. “These are birds we are talking about and they deserve your respect. Birds can fly. Now, correct me if I’m wrong, but none of you can fly as well as a bird, can you?” She cast her icy eyes around the room. “Can any of you fly as well as a bird? And isn’t that why we learn about birds, to learn about flying?”

Fagin squawked. “No feathers. No wings. No crackers for you.”

“There there, Fagin,” said Miss Dimwiddie, patting the bird on the head. “I’ll have you know that the blue-footed booby is one of the most spectacular hunters in the bird kingdom. These birds actually stop in mid-flight and drop into a headlong dive into the ocean from heights of eighty feet.”

The praying mantis boy snorted. “Nathan Johnson has flown higher than that and he isn’t a bird.”

Miss Dimwiddie narrowed her eyes. “Excuse me?”

“Nathan Johnson,” said the boy. “He’s the Wing who won the Flyfest three years running. He can fly ten storeys in the air, go into a free fall and stop two feet before he hits the ground.”

“Really?” said Miss Dimwiddie. “How informative.”

“Ugly boy,” Fagin crowed. “Stupid boy.”

Miss Dimwiddie smiled. “You’re new. Have you gotten your name yet?”

“No,” said the boy. “But I like to call myself—”

Miss Dimwiddie cut him off. “So you admire Nathan Johnson?”

“Yeah,” said the boy. “Doesn’t everyone?”

The students started whispering, much to Miss Dimwiddie’s annoyance. “I admire birds,” said Miss Dimwiddie. “They are the true Wings.”

Mantis Boy scowled. “I still think Nathan Johnson is the best Wing we’ve ever had.”

“Let me guess,” said Miss Dimwiddie. “You’re going to be just like him one day.”

The boy’s scowl got even deeper. “So what if I am?”

“We’ll see about that,” Miss Dimwiddie told him. “At Wing practice you can show everyone at Hope House that you’re better than birds. I’m sure you’ll put on a spectacular show.” She clapped her hands together. “Now let’s turn to the next chapter. Can anyone tell me why crows like shiny objects so much?”

The boy crossed his arms across his chest and stared at Miss Dimwiddie as if he wanted to take a shiny object and thwack her in the head with it. Gurl wished he would, as it could keep them both from talking about birds and about flying. Gurl was so sick of hearing about flying. What was so great about it anyway? What was the point?

She looked down at her hands and tried to convince herself that she was more special because she couldn’t fly. Being a leadfoot made her watchful and patient. It had got her out of Hope House. It had got her a fabulous dinner. And, most importantly, it had got her the cat.

The cat!

After class, Gurl rushed back to the girls’ dorm. She got down on her knees and pulled the box out from under her bed—just enough so that she could see inside, but not far enough that any of the other girls could. The little cat was still there, curled in a tight ball. Gurl breathed a sigh of relief, thankful that the cat hadn’t disappeared.

No, you’re the one who disappears, she thought. But of course that couldn’t be true.

The cat rolled over and stretched, letting Gurl scratch its belly. She didn’t even know this cat and it wasn’t hers, but she already loved it more than she had ever loved anything else. If a tree falls in a forest, and no one is around, she thought, does it make a sound?

And then she thought: Yes. It purrs.

Chapter 3 The Chickens of Hope House

DAYS PASSED AND GURL WAS more and more convinced that though the cat was real, vanishing had been a trick of the light or of her imagination. Every morning, Gurl got up, put the little cat in the box under her bed and warned her to stay put. Remarkably, she did stay, sleeping all day only to wake up to the bits of food Gurl had saved from that night’s dinner. (For some reason, the cat never seemed to need a litterbox and never left a mess. Gurl was too grateful to think about it.) Every night, the little cat sprawled across Gurl’s feet, purring strongly enough that Gurl felt the vibrations all the way up into her heart. Though she felt guilty that the cat was trapped under the bed all day, Gurl told herself that it was only for a while and that eventually she would let the cat go.

Eventually.

Meanwhile, she daydreamed and people-watched through her classes, trying very hard not to be noticed—especially at Wingwork practice. There Coach Bob led the children in their flying exercises, walking back and forth between the rows of kids, his whistle bouncing up and down on his big round belly. “Crouch!” he shouted with his great trapdoor mouth. “Spring! Up!” He watched the kids attempt to get themselves into the air, then took his hat off and threw it to the ground. “Ruckus!” he said. “Do you call that a spring? I call that a wobble. Hogwash, when I told you to use your arms as levers, I meant use them as levers. Are you an orphan or an air traffic controller? And Blush! This is not a game! This is Wingwork! You kids will never be Wings with all this goofing around! Now, all of you, again!” He pointed at two kids who were jumping up and deliberately crashing into each other. “Lunchmeat and Dillydally, see me after practice!”

Gurl followed Coach Bob with a yardstick and a notepad. After the specialist had declared her hopelessly landlocked, Mrs Terwiliger and Coach Bob had excused her from Wingwork and given her a job: record the heights of everyone’s practice leaps. It wasn’t much of a job because the children of Hope House could fly about as well as chickens could, which is to say not very well at all.

Gurl stopped next to Ruckus and measured his next leap. Though he did everything that Coach told him to do—crouched as low as he could go, used his arms for levers—Gurl got a measurement of two feet. Ruckus always got a measurement of two feet.

Ruckus dropped to the ground. Beads of sweat gave him a frosty moustache that gleamed against his chocolate skin. “What was it?” he asked her, breathing hard.

“Two,” she said.

“It was more than two!”

“No, it was two.”

“It was at least three.” His squinty eyes darted left and right, and he dragged a hand through his crazy caterpillar hair.

Gurl sighed and wrote “2” on her notepad.

Ruckus did what he usually did: grabbed the notebook from her hand, tore off the top page and stuffed it into his mouth, chewing defiantly. After he swallowed, he said, “Who’d believe you? You can’t even get your toes off the ground.”

“Neither can you,” said Gurl, under her breath.

“Leadfoot!” Ruckus yelled.

“Ruckus, stop making such a ruckus!” said Coach Bob. “And Gurl…” he began, then trailed off. Coach Bob didn’t like to shout at her. Coach Bob felt bad for her. At least the other kids might fly one day.

She didn’t hope to fly. In her daydreams, no one could. The whole city was rooted as firmly as she was. She imagined a life for herself in her non-flying world, a nice life—not amazing, but nice. A girl who lives with her parents in a tidy brownstone walks to her after-school job as an ice-cream taster. She says the rum banana is good, but the huckleberry swirl needs more swirl. “You can never have enough swirl,” she tells Mr Eiscrememann, the manager of the ice-cream store. “You’re right,” Mr Eiscrememann says. “What a smart girl! What an observant girl! Here, have a sundae!”

Just then, Mrs Terwiliger, the matron of Hope House, flew out of the main building, her skirt so tight in the knees that she looked like an airborne eggwhisk. For a long terrible moment Gurl worried that the cat had been discovered in the box under her bed.

“Coach Bob? Is there trouble? I heard shouting from my office.” She noticed Gurl and smiled. “Oh, hello, Gurl. I didn’t see you standing there.”

Gurl frowned. Mrs Terwiliger had been saying that ever since Gurl could remember, but she’d never thought about it before.

“Gurl, I said ‘hello’.”

“Hello, Mrs Terwiliger,” Gurl said.

“That’s better,” said Mrs Terwiliger, while Coach Bob inspected the brim of his Wing cap. Mrs Terwiliger had been the matron of Hope House for more years than anyone could count. With her tight skirts, poofy blonde hair, drawn-on eyebrows and facelifts that stretched her toffee apple-red lips so wide that the corners nearly grazed her ears, nobody knew how old she was. Somewhere between forty and eighty went the guesses. It was she who started the tradition of naming the children who came to Hope House after their personal characteristics and temperaments. Thus, the baby boy who threw tantrums became Ruckus, the boy with the slick, ruddy skin became Lunchmeat, the boy who was full of excuses became Hogwash and the girl who couldn’t keep her fingers out of her nose became Digger. “It’s just like how the Indians used to name their children. Those Indians were so colourful! Running Bear, Clucking with Turkeys, Little Pee Pee.”

Gurl thought it was lousy to blame the poor Indians for the dumb stuff Mrs Terwiliger called the kids of Hope House. Gurl got her own name because Mrs Terwiliger kept losing her as a baby. “I would turn around and poof! You were gone! And I would say to myself: Self, where is that GURL? Where has that GURL gotten to? And then I’d open the linen closet, looking for some towels, and there you’d be. I suppose I should be grateful that you have no talent for flight. You would have just floated away and no one would have been the wiser. Like a little cloud. Hmmm…Little Cloud would have been a nice name too, wouldn’t it? No?”

Now Gurl wondered about her name, about getting lost all the time. Was it possible that what happened in the alley had happened before? And would it happen again?

Mrs Terwiliger lowered her voice. “How are the children doing today, Bob?” Each syllable uttered by Mrs Terwiliger was enunciated in the most exaggerated fashion, as if the world were populated entirely with lip-readers. “How are they flying?”

Coach Bob shoved the cap back on his head. “What do you think? It’s like they’ve got bowling balls stuffed in their underwear.”

“Oh, dear. I had hoped…” said Mrs Terwiliger. She always hoped that the kids would do better, maybe one day make their way on to a Wing team and make Hope House the talk of the town, but they never did. Gurl looked through the chainlink fence, out on to the street. The people buzzed by, on foot, on flycycles, on rocket boards, in cars, flitting off to wherever they had to be. Some wore business suits, others wore chains and nose rings, but most didn’t notice the kids of Hope House jumping, straining, failing. If they did happen to look, they frowned in concern and pity or giggled in amusement. Even the crows that gathered in the single tree on the grounds seemed to laugh at them: “Ha! Ha! Ha!”

Gurl wondered if that was why Mrs Terwiliger made them practise outside. She kept a metal donation box bolted to the gate, which was often stuffed to the brim with dollar bills. What, thought Gurl, did she spend all that money on? She certainly didn’t spend it on the kids at Hope House. The clothes were tattered, the shoes too small, the food inedible and the dorms freezing. The few times that they got to go out on field trips, Mrs Terwiliger took them to Times Square, gave them each a can full of Hope House pencils and told them to sell the pencils to passersby for a dollar each. She said that it was a character-building exercise.

“Hey!” bellowed a voice. “What are you looking at?”

Mrs Terwiliger, Coach Bob and Gurl turned, expecting to see Ruckus causing a ruckus again. But it wasn’t Ruckus; it was the nameless new boy. He was shouting at a woman who had stopped her flycycle long enough to tape some sort of notice to the front gate. “I said, what are you looking at?”

The woman, dressed in a neon-pink sweatshirt that fell off one shoulder, glanced behind her, as if she assumed he was talking to someone else.

“Yeah, I mean you!” shouted the boy. “What are you looking at?”

The woman held up a hand. “Are you talking to me? I don’t think you’re talking to me, ya little snot.”

Bug Boy laughed. “I think I am tawkin’ to ya,” he said, imitating her thick city accent.