Полная версия

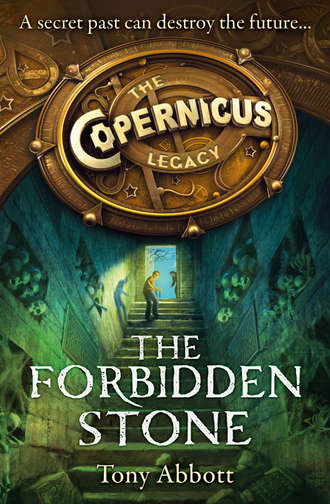

The Forbidden Stone

“I knew it,” Wade growled. “Come on.”

“Fine, but are we still talking about nothing to eat?”

Wade laughed. “Sorry, bro.”

Darrell mumbled something, then hummed a raucous guitar solo as they made their way back up to the dome. Good, thought Wade. This is what Darrell did when he was more or less happy. Obsess about food and hum riffs.

Five minutes later, the boys pushed through the door of the old observatory, and the atmosphere of the large room washed over them like a wave of the past.

Darrell whistled. “You weren’t kidding, steampunk!”

Centered directly below a huge copper dome stood the famous Painter Hall telescope. A twelve-foot-long iron tube built in 1933, it was poised on a brick platform and was meticulously balanced by a giant weight, making it easily maneuverable into any position. Wade explained that the scope’s lens measured a mere nine inches across—compared to, say, the McDonald Observatory’s scope, whose mirror was thirty-six feet across. But this was a historical instrument, and Wade loved that. He loved the places where science and history crisscrossed. There was something exciting about lenses and gears and mechanisms that made exploration that much more, what was the word, human.

Wade had long had a thing for the old Painter Hall telescope, ever since his father first brought him into that round room. It was there he learned to locate the planets and constellations. It was in that observatory that he’d read the myths that lay behind their exotic names. It was there where he’d come to appreciate his own tiny place in the vast cosmos of space.

Where math and magic become one.

“Not bad, huh?”

“Not bad at all.” Darrell jumped up to the platform. “Cables, cranks. Levers. A clock drive! Mechanical future stuff. I love it! What awesome stuff can it do?”

“Not much in the daytime, but we’ll come back tonight for some real stargazing. Don’t mess with anything until I find the operating instructions. You’ll love the way it swings around with just a touch.” Wade plopped down at a small desk near the door. His father was writing a history of the telescope and had set up a research station there. “Just wait. Mars will be as close as a dinner plate.”

“I wish I were close to a dinner plate,” said Darrell. “Do you still have nothing to eat?”

“Since the last time you asked? No. But why don’t you check those pockets you never check?”

“Because I obviously don’t carry food with me … oh.” Darrell pulled a slender packet from his other pocket. “Gum is food, right?”

“It is if you swallow it,” said Wade.

“I always do.”

Before he’d met Darrell and his new stepmom, Sara, three years ago, Wade had hoped for the longest time that his real mother and father would get back together. He was crushed to realize they weren’t going to, and he was still having trouble accepting that the past was really the past. But he saw his real mom often (she lived in California now) and was coming to understand that you move on and learn to live with lots of stuff. He also had to admit that the new families were working out really well.

“Can you believe Mom’s going to be lost in the jungles of South America for a week?” Darrell asked from the platform. “Well, not lost, but hunting down some crazy writer?”

“I know, a week with no phones, no electricity, nothing.”

“Except bugs,” said Darrell. “Lots of bugs. Then she flies to New York. Then London. My jet-setting mom.”

“Sara’s supercool,” Wade said.

“Yes. My mother is.”

Any way you looked at it, the best part of the deal was Darrell himself. From the instant the two boys were introduced, he’d become the brother Wade had always wanted. They complemented each other in just about every way, but at the same time, Wade and Darrell couldn’t be more different.

Darrell had short dark hair, olive skin, and deep brown eyes that he got from his Thai father. Wade was fair-skinned, sandy-haired, and lanky. Darrell was five feet four and a guitarist of strange loud stuff that might be really excellent or might just be loud. Wade was three inches taller and owned an iPod full of Bach, because Bach was not loud, was the most mathematical of composers, and was someone his mother had taught him to love. Darrell was a junior tennis pro. Wade wore sneakers like a junior tennis pro. Darrell was comfortable with just about everyone. Wade felt more comfortable with Darrell than he did with himself. Finally, Darrell was usually smiling, even when he was sleeping, while Wade had invented neurotic worrying.

And he felt a sudden jolt of worry at exactly that moment.

While searching for the telescope’s operating manual on the desk, he’d accidentally moved the mouse on his father’s computer. The screen saver flickered away and an email message popped up. Without wanting to, Wade noticed the sender’s name.

Heinrich Vogel.

“No kidding?” Wade whispered. “Uncle Henry?”

“No. The name is Darrell,” said Darrell from the platform. “I thought being my stepbrother for three years you would know that.”

“No. Dad got an email from Uncle Henry. We were just talking about him. You know he’s not really my uncle, right? He was Dad’s college teacher in Germany. I haven’t seen him since I was seven.”

Darrell hopped down the stairs and peered over Wade’s shoulder. “Emails are private. Don’t read it. What does it say?”

Wade tried not to read it, but his eyes strayed.

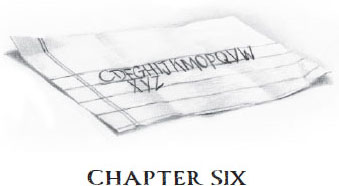

Lca guygas eamizub zb.

Bluysna luynaedab odxx sio wands.

Juilatl lca Hyndblaub xanytq.

Rdse lca loaxma uaxdtb.

Qiz yua lca xybl.

Darrell frowned. “Does Dad read German? Or is that Russian?”

“Neither. It’s got to be some kind of code.”

“Code. Wait, is our dad a spy? He’s a spy, isn’t he? Of course he’s a spy, he never told me he was, which is exactly what a spy would do. I knew it. It’s that beard. No one really knows what he looks like under there.”

“Darrell, no.”

“He’s probably a double agent. That’s the best kind. No one’s a single agent anymore. Or, no, a triple agent. That’s even better. Wait, what is a triple agent—”

The door squeaked open. “So there you are!”

Wade shot up from the desk the moment his father entered the observatory. “Nothing!” he said.

Roald Kaplan had run track in high school, had been a champion long-distance runner in college, and still ran the occasional marathon. He was trim and tall and handsome behind sunglasses and a dark, close-cut beard. “Sara’s safely off on her flight to Bolivia. Thanks for hanging out here, while we did our last-minute zipping around. What are you guys up to?”

“Well,” Darrell piped in, “I found gum.”

“And I …,” Wade said, “… didn’t?”

Darrell cleared his throat. “Wade’s odd behavior means he’s worried. Which, I know, is not breaking news, but he found something bizarro on your computer …”

Wade pointed at the computer screen. “Dad, I’m sorry, but it was an accident that I saw the screen at all. I know I shouldn’t have read the email, but I saw it, and … what’s going on? It’s from Uncle Henry, but it looks like code.”

Dr. Kaplan paused for a long moment. His smile faded away. He leaned over Wade and tapped the keyboard. The email printed out on a nearby printer. Then he deleted the message and shut the computer off.

“Not here. Not now.”

“Can you at least tell us why Uncle Henry’s writing to you in code?” Wade asked when they got into the car. “Is he in trouble? Or in danger? Dad, are we in danger?”

“You worry too much,” said Dr. Kaplan, unconvincingly.

“Is Uncle Henry a spy?” asked Darrell. “Because if he’s a spy, that’s huge. A spy in the family would actually be terrific and awesomely cool. As you probably already know, I would make a perfect spy—”

“Boys, please,” Dr. Kaplan said, weaving through campus traffic and onto the streets. “I’m sure Uncle Henry is just fine, and I’m almost positive it’s some kind of joke message. In any case, it won’t make sense to you—or even to me—until we get home. There are a couple pieces of the puzzle I need to figure it out. Until then …”

Puzzle? Wade didn’t know what to say. He sat quietly looking out the window for the next twenty minutes as they drove from campus into the hills west of Austin.

Darrell did not sit quietly. “I think I have it. Uncle Henry is a professor in Germany, but he’s secretly doing spy stuff. He’s a master cryptographer, and he’s trying to recruit you to be a spy too. Dad, if you can’t do it, I’ll do it. Sure. I know professors make a good cover. They pretend to sit in their offices all sleepy over their books and stuff while secretly they’re running all kinds of spy missions. But middle school kids are even better. No one would ever suspect us. Wade, you could be a spy, too. Of course, you’d do the desk stuff while I go around the world with my band as a cover. Not that the Simpletones would be a cover band. We’d play all original stuff. They call that being in the field. I’d be a field agent. Agent being the technical term for ‘spy’ …”

Darrell hadn’t stopped talking, but as he was often forced to do when his stepbrother thrashed on guitar, Wade had to tune him out to be able to think.

Ever since Uncle Henry had given him the antique celestial map on his seventh birthday, Wade had been a fanatic about star maps and charts and the courses and routes of celestial bodies. He’d stayed up every night for weeks studying the map by moonlight and flashlight. Of course, he learned most things from his father, a brilliant astronomer, but it was probably Uncle Henry’s star map that stole his deeper imagination. The chart was old and strange and mysterious, and in his mind Wade associated all those qualities with the stars themselves. Between his father and Uncle Henry, Wade learned to love the night sky more than anything.

When they finally turned into the driveway of a sprawling home overlooking a shallow valley, Darrell practically exploded in the backseat. “Uncle Henry is a spy! Someone’s casing our house!”

As Dr. Kaplan slowed the car, a shape darted along the side garden and disappeared under the roof that hung over the front door.

Wade stiffened. “Dad, tear out of here—”

“Yoo-hoo!”

A girl in shorts and a stylishly slashed T-shirt strolled out from under the overhang to the car, wheeling an orange suitcase behind her.

It was Lily Kaplan, Wade’s first cousin, his father’s niece. “Surprise, people!”

“Lily? This is a surprise,” said Dr. Kaplan, rolling down the window.

“Like, what are you even doing here?” Darrell asked.

“Like, nice to even see you, too,” Lily said, snapping a picture of Darrell on her cell phone. “Oh, I’m posting that face.” Her thumbs flew over the phone while she talked.

“I’m supposed to be on vacation with my parents in Paris right now,” she said. “That’s in France. One of my school friends was even coming with me. We were going to shop. Well, I was going to shop. Big-time. But then Mom got the flu. Also big-time. Then Dad had to fly to Seattle for work. So good-bye France, and that’s why he called you, Uncle Roald, and … wait. You did talk to my dad? He said he was going to call you.”

Dr. Kaplan frowned. “I …” He fished out his cell phone and tapped it several times. “It must have run out of battery. I’m so sorry I didn’t get his message.”

Lily clucked her tongue. “No one should ever let his battery run down. I never let my battery run down. Your phone is like your brain. More important, even. Anyway, my dad dropped us here for the week and—ta-da!—here we are.”

Something sparked in Wade’s head. “Us? We? Here we are?”

Lily turned and made a little wave toward the house. “Becca came with me. Wade, you remember Becca, right?”

Of course he did.

Becca Moore.

The instant Becca walked out of the shade of the overhang, Wade stood up like a soldier at attention. He couldn’t stop himself. It was instinctive and weird. He knew it was. But more than being weird, it hurt, because Wade was still in the car. You don’t stand up in cars. Even convertibles, which his dad’s car was not. As Wade jammed his head into the ceiling, he knew it must look epically dumb.

Guys didn’t stand up for just anyone.

But then, Becca Moore was not just anyone. She was … interesting. His brain wouldn’t let him go any further than that.

Interesting.

Becca was born in Massachusetts and had moved to Austin when she was eight. She was tall and fair and had long brown, almost black hair tied in a loose ponytail. Wade was a little afraid of her because she was so smart, but she didn’t broadcast it and was almost as quiet as he was, which was another cool thing about her. As she walked over to the car, she was wearing a faded red 2012 Austin Teen Book Festival T-shirt, slim blue jean leggings, and mouse-gray ballet flats so soft they made no more sound than if she were barefoot.

Interesting.

Dr. Kaplan got out of the car and hugged both girls. “Well, we’re glad to have you visit. Come on in!”

Darrell couldn’t stop laughing as Wade unfolded himself from the car and limped to the front door.

No sooner had they all piled inside than Lily spun around. “Pose!” She snapped another picture with her phone. “So awesome. Wade with his eyes closed. Darrell looking like … Darrell.” Then she found a seat in the living room, tugged a sleek tablet computer from her bag, and instantly began to type on its touch-screen keyboard. She looked up. “I’m writing a travel blog. But you knew that, right?”

No one knew that. If Wade had realized he would end up on the internet, he might have combed his hair that morning. Or washed it.

Lily grinned as she typed. “Vacation Day One. The Big Disappointment. A week with my cousins Wade and Darrell. I can barely bring my fingers to type these words …”

Darrell frowned. “Ha. And also, ha.”

Tearing his eyes away from Becca, who sat quietly on the couch next to Lily, Wade watched his father move distractedly around the living room. The coded email from Uncle Henry was obviously on his mind. Of course it was. Code? What did code even mean, except keeping a secret from someone? Who would Uncle Henry and his dad need to keep secrets from?

When the snappy conversation between Lily and Darrell finally paused, he spoke up. “Dad, the email?”

“I need your celestial map,” his father said, as if he’d been waiting for a lull, too. “The star chart Uncle Henry gave you when you were seven.”

Wade blinked. “Really? Why?”

“You’ll see,” his father said.

In the quiet of his room, Wade slid open the top drawer of his desk. He removed the leather folder as he had the night before. The map, so precious and so rare, would now, suddenly, be the center of everyone’s attention. But why did Dad want the chart? Puzzling over this, he brought it into the dining room, where he found them all sitting around the table.

His father pulled out a chair for him. “Wade, open the map, please …”

He unzipped the folder and opened it flat, revealing the thick sheet of parchment creased over itself twice. He saw, as he hadn’t in the darkness of his room the night before, faint, penciled letters on the backside, reading, Happy Birth-day, Wade. Carefully, he unfolded the parchment on the table and spread it out faceup.

Becca leaned over it, her eyes glowing. “Wade, this is so gorgeous. Wow …”

“Thanks,” he said quietly.

Spread out, the map was about the size of a small poster. It had been engraved in 1515 and was exquisitely hand painted. The heavens were colored deep blue, and the original forty-eight constellations described by the ancient Greek astronomer Ptolemy were drawn and starred in silver inks. Crater, Lyra, Orion, Cassiopeia, all the others. Evenly spaced around the map’s edge was a sequence of letters in gold forming an incomplete alphabet, which had always puzzled Wade and about which his father had offered no real explanation.

“Okay, so,” Dr. Kaplan said, taking a deep breath. “First we have the email.” He produced the printed email from his blazer pocket, then carefully traced his fingers over the letters bordering Wade’s star map. “Uncle Henry gave you this chart for your birthday, knowing you would like it.”

“I love it,” Wade said almost reverently. “It’s what really got me super-interested in the stars.”

“I know,” his father said. “Maybe you don’t remember me telling you, but it wasn’t the first time I had seen this map. Heinrich showed it to me while I was still a student, quite a few years before you were born. He had a little apartment then; he still does.”

“Have you seen him since then?” Becca asked.

“Once, then letters, email once in a while,” he said. “Heinrich had always been a collector of antiques. One night twenty or so years ago, in front of me and some other students, he unfolded five identical printings, all hand-colored, of the same map from the sixteenth century. This map. As we all watched, he took out a pen, dipped it in gold ink, and without a word, inked an alphabet around the edge of each one.”

“But the alphabet is messed up,” Lily said. “It’s only got … seventeen letters.” On her tablet she typed in the gold-inked letters framing the star map, while Darrell did the same on a yellow pad.

C D F G H I J K M O P Q V W X Y Z

“Of course.” Dr. Kaplan slipped on a pair of reading glasses. “We noticed the same thing. Heinrich told us our alphabets were one part of a cipher—a code—of his own invention. He said we might have to use it someday. Before we ever needed it, he said, he would see that we each received one copy of the map. Then he put them away before we could really do any figuring. And that was that. I never thought much about the maps again until your seventh birthday, Wade, when he gave you this one. He brushed off any mention of the code then. I assumed it didn’t matter anymore.”

Darrell shook his head slowly. “But it does matter. And it proves I was right. He was a spy. He was pretending to be a professor, but he was a secret agent.”

Dr. Kaplan cracked a smile. “I really don’t think so. He’s retired now, but he was one of the foremost physicists of his day. When he first showed us the maps, he swore us to secrecy. He called our little group of five students Asterias. That’s the Latin name for the sea star. We were, Heinrich said, like the five arms of the starfish, and he was the head. It seemed a little silly at the time. A professor’s whimsy. But we were graduating and going our separate ways, so we all agreed. In the last few years I lost communication with most of them, and he’s never asked me to use the code. Until today.”

Wade breathed in to try to calm himself. It didn’t work. A hundred questions collided in his brain. “Are you saying that the cipher on the map will decode the email?”

“But not all the letters are there,” said Becca. “If it’s a standard substitution code, it needs all twenty-six letters.”

Everyone looked at her.

“Substitution code?” said Darrell. “Uh-huh. Putting aside for a moment what substitution codes even are, how do you know about them?”

Becca blushed a little. “I read. A lot. Last summer I read all the Sherlock Holmes stories. You know what I mean, right, Dr. Kaplan?”

He smiled. “I do. Sherlock Holmes solves substitution codes in several of the stories. When we asked Heinrich about the missing letters, he just winked and slyly tapped the side of his nose. We pressed him about what he meant, and he said, ‘when things are missing, you look for them!’ You’re all pretty brainy, so the first step for us is, what letters are missing?”

Lily had apparently already figured it out and told them with a grin. “A, B, E, L, N, R, S, T, and U!”

“Good,” Dr. Kaplan said. He wrote them on Darrell’s pad.

A B E L N R S T U

“Nine letters. The cipher begins as a fairly simple Caesar code, a substitution code originated a couple of thousand years ago by Julius Caesar for his private letters. Heinrich was a student of ciphers, and he modified this in his own way.

“So, the letters not on the map form a secret word or phrase. You unscramble the missing letters to find the words, then put them at the beginning of the alphabet to make the full twenty-six letters again.”

“Nine letters could spell a lot of words,” said Darrell.

Dr. Kaplan nodded. “But they should somehow be familiar to the person for whom the code is intended …” He paused, stroking his chin. “My diary. I kept a journal then, a student notebook, where I wrote down lecture notes and random things. It’s in my office. Hold on.” He left the room at a trot.

“We can start,” said Becca. “A, B, E, L, N, R, S, T, and U. Let’s think.”

The dining room went quiet, except for Darrell’s pencil scratching and occasional humming and Lily’s fingers tapping on the tablet’s screen. Becca frowned and looked off across the room.

Wade tried to think, but the image of Uncle Henry inking the maps in gold was mesmerizing. Was it by candlelight, their student faces glowing? Was his apartment as hushed as their dining room was right now? Why did he do it in the first place?

His father returned, leafing through a small black notebook. “Maybe the answer is somewhere in here …”

“I get the words rest, nut, and eat,” Darrell said finally.

“Of course you do,” said Lily. “I see ears.”

“I get lean burst,” said Becca with a smile. “Do I get a prize for using all the letters?”

Wade resisted jumping up and shouting, “Yes, you do!”

But the more he studied the letters, the more they began to shift places like the panels in one of those number slide puzzles. This was how his mind often solved math problems. His father said he was a natural at numbers. And now, apparently, at letters, too.

Common combinations … S … T … slid forward and back … vowels moved and moved again. Fixing his eyes on the letters, Wade went through them again, again, then click. Solved. Or sort of solved. He cleared his throat. “Well …”

Four faces looked at him.

“One thing the letters spell is blue star with an extra n,” he said. “I don’t know what the n stands for, but a blue star is a real thing. If a star appears blue, it means it’s approaching Earth.”

Dr. Kaplan stared at the letters on the pad, nodding. Then he turned to the last page in his notebook and smiled. “Oh, boy. Close. Very close. But look.”

As they watched him, he slowly rewrote blue star n as blau stern.

“Blau stern?” said Becca. “That’s blue star in German.”

“Exactly,” Dr. Kaplan said, showing them the words in his notebook. “Blau Stern was the name of the café in Berlin where we met after classes—”

“I knew it!” said Darrell. “Your spy hangout!”

Roald blew out a fast breath. “Hardly, Darrell. But we’ve done it. Good work. What we do now is take the secret phrase and add it to the beginning of the incomplete alphabet to make a full twenty-six letters.”