Полная версия

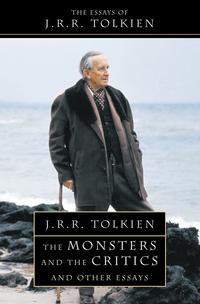

The Monsters and the Critics

Beowulf knows, of course, of hell and judgement: he speaks of it to Unferth; he declares that Grendel shall abide miclan domes and the judgement of scir metod; and finally in his last examination of conscience he says that Waldend fira cannot accuse him of morðorbealo maga. But the crimes which he claims to have avoided are closely paralleled in the heathen Völuspá, where the grim hall, Náströndu á, contains especially menn meinsvara ok morðvarga (perjurers and murderers).

Other references he makes are casual and formal, such as beorht beacen Godes, of the sun (571). An exceptional case is Godes leoht geceas 2469, describing the death of Hrethel, Beowulf’s grandfather. This would appear to refer to heaven. Both these expressions have, as it were, inadvertently escaped from Christian poetry. The first, beacen Godes, is perhaps passable even for a heathen in this particular poem, in which the theory throughout is that good pagans, when not tempted or deluded by the devil, knew of the one God. But the second, especially since Beowulf himself is formally the speaker, is an item of unsuitable diction – which cannot be dismissed as a later alteration. A didactic reviser would hardly have added this detail to the description of the heathen king’s death: he would rather have removed the heathen, or else sent him to hell. The whole story alluded to is pagan and hopeless, and turns on blood-feud and the motive that when a son kills his brother the father’s sorrow is intensified because no vengeance can be exacted. The explanation of such occasional faults is not to be sought in Christian revision, but in the fact that before Beowulf was written Christian poetry was already established, and was known to the author. The language of Beowulf is in fact partly ‘re-paganized’ by the author with a special purpose, rather than christianized (by him or later) without consistent purpose. Throughout the poem the language becomes more intelligible, if we assume that the diction of poetry was already christianized and familiar with Old and New Testament themes and motives. There is a gap, important and effective poetically whatever was its length in time, between Cædmon and the poet of Beowulf. We have thus in Old English not only the old heroic language often strained or misused in application to Christian legend (as in Andreas or Elene), but in Beowulf language of Christian tone occasionally (if actually seldom) put inadvertently in the mouth of a character conceived as heathen. All is not perfect to the last detail in Beowulf. But with regard to Godes leoht geceas, the chief defect of this kind, it may be observed that in the very long speech of Beowulf from 2425–2515 the poet has hardly attempted to keep up the pretence of oratio recta throughout. Just before the end he reminds us and himself that Beowulf is supposed to be speaking by a renewed Beowulf maðelode (2510). From 2444 to 2489 we have not really a monologue in character at all, and the words Godes leoht geceas go rather with gewat secean soðfœstra dom as evidence of the author’s own view of the destiny of the just pagan.

When we have made allowance for imperfections of execution, and even for some intentional modification of character in old age (when Beowulf becomes not unnaturally much more like Hrothgar), it is plain that the characters and sentiments of the two chief actors in the poem are differently conceived and drawn. Where Beowulf’s thoughts are revealed by the poet we can observe that his real trust was in his own might. That the possession of this might was a ‘favour of God’ is actually a comment of the poet’s, similar to the comment of Scandinavian Christians upon their heathen heroes. Thus in line 665 we have georne truwode modgan mœgenes, metodes hyldo. No and is possible metrically in the original; none should appear in translation: the favour of God was the possession of mœgen. Compare 1272–3: gemunde mœgenes strenge, gimfœste gife ðe him God sealde.36 Whether they knew it or not, cuþon (or ne cuþon) heofena Helm herian, the supreme quality of the old heroes, their valour, was their special endowment by God, and as such could be admired and praised.

Concerning Beowulf the poet tells us finally that when the dragon’s ruinous assault was reported, he was filled with doubt and dismay, and wende se wisa þœt he Wealdende ofer ealde riht ecean Dryhtne bitre gebulge. It has been said that ofer ealde riht, ‘contrary to ancient law’, is here given a Christian interpretation; but this hardly seems to be the case. This is a heathen and unchristian fear – of an inscrutable power, a Metod that can be offended inadvertently: indeed the sorrow of a man who, though he knew of God, and was eager for justice, was yet far estranged, and ‘had hell in his heart’.

(c) Lines 175–88

These lines are important and present certain difficulties. We can with confidence accept as original and genuine these words as far as helle gemundon on modsefan – which is strikingly true, in a sense, of all the characters depicted or alluded to in the poem, even if it is here actually applied only to those deliberately turning from God to the Devil. The rest requires, and has often received, attention. If it is original, the poet must have intended a distinction between the wise Hrothgar, who certainly knew of and often thanked God, and a certain party of the pagan Danes – heathen priests, for instance, and those that had recourse to them under the temptation of calamity – specially deluded by the gastbona, the destroyer of souls.37 Of these, particularly those permanently in the service of idols (swylce wœs þeaw hyra), which in Christian theory and in fact did not include all the community, it is perhaps possible to say that they did not know (ne cuþon), nor even know of (ne wiston), the one God, nor know how to worship him. At any rate the hell (of fire) is only predicted for those showing malice (sliðne nið), and it is not plain that the freoðo of the Father is ultimately obtainable by none of these men of old. It is probable that the contrast between 92–8 and 175–88 is intentional: the song of the minstrel in the days of untroubled joy, before the assault of Grendel, telling of the Almighty and His fair creation, and the loss of knowledge and praise, and the fire awaiting such malice, in the time of temptation and despair.

But it is open to doubt whether lines 181–88 are original, or at any rate unaltered. Not of course because of the apparent discrepancy – though it is a matter vital to the whole poem: we cannot dismiss lines simply because they offer difficulty of such a kind. But because, unless my ear and judgement are wholly at fault, they have a ring and measure unlike their context, and indeed unlike that of the poem as a whole. The place is one that offers at once special temptation to enlargement or alteration and special facilities for doing either without grave dislocation.38 I suspect that the second half of line 180 has been altered, while what follows has remodelled or replaced a probably shorter passage, making the comment (one would say, guided by the poem as a whole) that they forsook God under tribulation, and incurred the danger of hell-fire. This in itself would be a comment of the Beowulf poet, who was probably provided by his original material with a reference to wigweorþung in the sacred site of Heorot at this juncture in the story.

In any case the unleugbare Inkonsequenz (Hoops) of this passage is felt chiefly by those who assume that by references to the Almighty the legendary Danes and the Scylding court are depicted as ‘Christian’. If that is so, the mention of heathen þeaw is, of course, odd; but it offers only one (if a marked) example of a confusion of thought fundamental to the poem, and does not then merit long consideration. Of all the attempts to deal with this Inkonsequenz perhaps the least satisfactory is the most recent: that of Hoops,39 who supposes that the poet had to represent the Danish prayers as addressed to the Devil for the protection of the honour of the Christengott, since the prayers were not answered. But this attributes to the poet a confusion (and insincerity) of thought that an ‘Anglo-Saxon’ was hardly modern or advanced enough to achieve. It is difficult to believe that he could have been so singularly ill instructed in the nature of Christian prayer. And the pretence that all prayers to the Christengott are answered, and swiftly, would scarcely have deceived the stupidest member of his audience. Had he embarked on such bad theology, he would have had many other difficulties to face: the long time of woe before God relieved the distress of these Christian Danes by sending Scyld (13); and indeed His permission of the assaults of Grendel at all upon such a Christian people, who do not seem depicted as having perpetrated any crime punishable by calamity. But in fact God did provide a cure for Grendel – Beowulf, and this is recognized by the poet in the mouth of Hrothgar himself (381 ff.). We may acquit the maker of Beowulf of the suggested motive, whatever we may think of the Inkonsequenz. He could hardly have been less aware than we that in history (in England and in other lands), and in Scripture, people could depart from the one God to other service in time of trial – precisely because that God has never guaranteed to His servants immunity from temporal calamity, before or after prayer. It is to idols that men turned (and turn) for quick and literal answers.

NOTES

1 The Shrine, p. 4.

2 Thus in Professor Chambers’s great bibliography (in his Beowulf: An Introduction) we find a section, §8. Questions of Literary History, Date, and Authorship; Beowulf in the Light of History, Archaeology, Heroic Legend, Mythology, and Folklore. It is impressive, but there is no section that names Poetry. As certain of the items included show, such consideration as Poetry is accorded at all is buried unnamed in §8.

3 Beowulf translated into modern English rhyming verse, Constable, 1925.

4 A Short History of English Literature, Oxford Univ. Press, 1921, pp. 2-3.1 choose this example, because it is precisely to general literary histories that we must usually turn for literary judgements on Beowulf. The experts in Beowulfiana are seldom concerned with such judgements. And it is in the highly compressed histories, such as this, that we discover what the process of digestion makes of the special ‘literature’ of the experts. Here is the distilled product of Research. This compendium, moreover, is competent, and written by a man who had (unlike some other authors of similar things) read the poem itself with attention.

5 I include nothing that has not somewhere been said by some one, if not in my exact words; but I do not, of course, attempt to represent all the dicta, wise or otherwise, that have been uttered.

6 The Dark Ages, pp. 252–3.

7 None the less Ker modified it in an important particular in English Literature, Mediæval, pp. 29–34. In general, though in different words, vaguer and less incisive, he repeats himself. We are still told that ‘the story is commonplace and the plan is feeble’, or that ‘the story is thin and poor’. But we learn also at the end of his notice that: ‘Those distracting allusions to things apart from the chief story make up for their want of proportion. They give the impression of reality and weight; the story is not in the air … it is part of the solid world.’ By the admission of so grave an artistic reason for the procedure of the poem Ker himself began the undermining of his own criticism of its structure. But this line of thought does not seem to have been further pursued. Possibly it was this very thought, working in his mind, that made Ker’s notice of Beowulf in the small later book, his ‘shilling shocker’, more vague and hesitant in tone, and so of less influence.

8 Foreword to Strong’s translation, p. xxvi: (See here)

9 It has also been favoured by the rise of ‘English schools’, in whose syllabuses Beowulf has inevitably some place, and the consequent production of compendious literary histories. For these cater (in fact, if not in intention) for those seeking knowledge about, and ready-made judgements upon, works which they have not the time, or (often enough) the desire, to know at first hand. The small literary value of such summaries is sometimes recognized in the act of giving them. Thus Strong (op. cit.) gives a fairly complete one, but remarks that ‘the short summary does scant justice to the poem’. Ker in E. Lit. (Med.) says: ‘So told, in abstract, it is not a particularly interesting story.’ He evidently perceived what might be the retort, for he attempts to justify the procedure in this case, adding: ‘Told in this way the story of Theseus or Hercules would still have much more in it.’ I dissent. But it does not matter, for the comparison of two plots ‘told in this way’ is no guide whatever to the merits of literary versions told in quite different ways. It is not necessarily the best poem that loses least in précis.

10 Namely the use of it in Beowulf, both dramatically in depicting the sagacity of Beowulf the hero, and as an essential part of the traditions concerning the Scylding court, which is the legendary background against which the rise of the hero is set – as a later age would have chosen the court of Arthur. Also the probable allusion in Alcuin’s letter to Speratus: see Chambers’s Widsith, p. 78.

11 This expression may well have been actually used by the eald geneat, but none the less (or perhaps rather precisely on that account) is probably to be regarded not as new-minted, but as an ancient and honoured gnome of long descent.

12 For the words hige sceal þe heardra, heorte þe cenre, mod sceal þe mare þe ure mœgen lytlað are not, of course, an exhortation to simple courage. They are not reminders that fortune favours the brave, or that victory may be snatched from defeat by the stubborn. (Such thoughts were familiar, but otherwise expressed: wyrd oft nereð unfœgne eorl, þonne his ellen deah.) The words of Byrhtwold were made for a man’s last and hopeless day.

13 Foreword to Strong’s translation, p. xxviii. (See here)

14 This is not strictly true. The dragon is not referred to in such terms, which are applied to Grendel and to the primeval giants.

15 He differs in important points, referred to later.

16 I should prefer to say that he moves in a northern heroic age imagined by a Christian, and therefore has a noble and gentle quality, though conceived to be a pagan.

17 It is, for instance, dismissed cursorily, and somewhat contemptuously in the recent (somewhat contemptuous) essay of Dr Watson, The Age of Bede in Bede, His Life, Times, and Writings, ed. A. Hamilton Thompson, 1935.

18 The Dark Ages, p. 57.

19 If we consider the period as a whole. It is not, of course, necessarily true of individuals. These doubtless from the beginning showed many degrees from deep instruction and understanding to disjointed superstition, or blank ignorance.

20 Avoidance of obvious anachronisms (such as are found in Judith, for instance, where the heroine refers in her own speeches to Christ and the Trinity), and the absence of all definitely Christian names and terms, is natural and plainly intentional. It must be observed that there is a difference between the comments of the author and the things said in reported speech by his characters. The two chief of these, Hrothgar and Beowulf, are again differentiated. Thus the only definitely Scriptural references, to Abel (108) and to Cain (108, 1261), occur where the poet is speaking as commentator. The theory of Grendel’s origin is not known to the actors: Hrothgar denies all knowledge of the ancestry of Grendel (1355). The giants (1688 ff.) are, it is true, represented pictorially, and in Scriptural terms. But this suggests rather that the author identified native and Scriptural accounts, and gave his picture Scriptural colour, since of the two accounts Scripture was the truer. And if so it would be closer to that told in remote antiquity when the sword was made, more especially since the wundorsmiþas who wrought it were actually giants (1558, 1562, 1679): they would know the true tale. (See here)

21 In fact the real resemblance of the Aeneid and Beowulf lies in the constant presence of a sense of many-storied antiquity, together with its natural accompaniment, stern and noble melancholy. In this they are really akin and together differ from Homer’s flatter, if more glittering, surface.

22 I use this illustration following Chambers, because of the close resemblance between Grendel and the Cyclops in kind. But other examples could be adduced: Cacus, for instance, the offspring of Vulcan. One might ponder the contrast between the legends of the torture of Prometheus and of Loki: the one for assisting men, the other for assisting the powers of darkness.

23 There is actually no final principle in the legendary hostilities contained in classical mythology. For the present purpose that is all that matters: we are not here concerned with remoter mythological origins, in the North or South. The gods, Cronian or Olympian, the Titans, and other great natural powers, and various monsters, even minor local horrors, are not clearly distinguished in origin or ancestry. There could be no permanent policy of war, led by Olympus, to which human courage might be dedicated, among mythological races so promiscuous. Of course, nowhere can absolute rigidity of distinction be expected, because in a sense the foe is always both within and without; the fortress must fall through treachery as well as by assault. Thus Grendel has a perverted human shape, and the giants or jōtnar, even when (like the Titans) they are of super-divine stature, are parodies of the human-divine form. Even in Norse, where the distinction is most rigid, Loki dwells in Asgarðr, though he is an evil and lying spirit, and fatal monsters come of him. For it is true of man, maker of myths, that Grendel and the Dragon, in their lust, greed, and malice, have a part in him. But mythically conceived the gods do not recognize any bond with Fenris úlfr, any more than men with Grendel or the serpent.

24 The Genesis which is preserved for us is a late copy of a damaged original, but is still certainly in its older parts a poem whose composition must be referred to the early period. That Genesis A is actually older than Beowulf is generally recognized as the most probable reading of such evidence as there is.

25 Actually the poet may have known, what we can guess, that such creation-themes were also ancient in the North. Voluspá describes Chaos and the making of the sun and moon, and very similar language occurs in the Old High German fragment known as the Wessobrunner Gebet. The song of the minstrel lopas, who had his knowledge from Atlas, at the end of the first book of the Aeneid is also in part a song of origins: hic canit errantem lunam solisque labores, unde hominum genus et pecudes, unde imber et ignes. In any case the Anglo-Saxon poet’s view throughout was plainly that true, or truer, knowledge was possessed in ancient days (when men were not deceived by the Devil); at least they knew of the one God and Creator, though not of heaven, for that was lost. (See here)

26 It is of Old Testament lapses rather than of any events in England (of which he is not speaking) that the poet is thinking in lines 175 ff., and this colours his manner of allusion to knowledge which he may have derived from native traditions concerning the Danes and the special heathen religious significance of the site of Heorot (Hleiðrar, œt hœrgtrafum, the tabernacles) – it was possibly a matter that embittered the feud of Danes and Heathobeards. If so, this is another point where old and new have blended. On the special importance and difficulty for criticism of the passage 175–88 see the Appendix.

27 Though only explicitly referred to here and in disagreement, this edition is, of course, of great authority, and all who have used it have learned much from it.

28 I am not concerned with minor discrepancies at any point in the poem. They are no proof of composite authorship, nor even of incompetent authorship. It is very difficult, even in a newly invented tale of any length, to avoid such defects; more so still in rehandling old and oft-told tales. The points that are seized in the study, with a copy that can be indexed and turned to and fro (even if never read straight through as it was meant to be), are usually such as may easily escape an author and still more easily his natural audience. Virgil certainly does not escape such faults, even within the limits of a single book. Modern printed tales, that have presumably had the advantage of proof-correction, can even be observed to hesitate in the heroine’s Christian name.

29 The least satisfactory arrangement possible is thus to read only lines 1–1887 and not the remainder. This procedure has none the less been, from time to time, directed or encouraged by more than one ‘English syllabus’.

30 Equivalent, but not necessarily equal, certainly not as such things may be measured by machines.

31 That the particular bearer of enmity, the Dragon, also dies is important chiefly to Beowulf himself. He was a great man. Not many even in dying can achieve the death of a single worm, or the temporary salvation of their kindred. Within the limits of human life Beowulf neither lived nor died in vain – brave men might say. But there is no hint, indeed there are many to the contrary, that it was a war to end war, or a dragon-fight to end dragons. It is the end of Beowulf, and of the hope of his people.

32 We do, however, learn incidentally much of this period: it is not strictly true, even of our poem as it is, to say that after the deeds in Heorot Beowulf ‘has nothing else to do’. Great heroes, like great saints, should show themselves capable of dealing also with the ordinary things of life, even though they may do so with a strength more than ordinary. We may wish to be assured of this (and the poet has assured us), without demanding that he should put such things in the centre, when they are not the centre of his thought.

33 Free as far as we know from definite physical location. Details of the original northern conception, equated and blended with the Scriptural, are possibly sometimes to be seen colouring the references to Christian hell. A celebrated example is the reference in Judith to the death of Holofernes, which recalls remarkably certain features in Vðluspá. Cf. Judith 115: wyrmum bewunden, and 119: 01ðam wyrmsele with Vōl. 36 sá’s undinn salr orma hryggjum: which translated into O.E. would be se is wunden sele wyrma hrycgum.

34 Such as 168–9, probably a clumsily intruded couplet, of which the only certain thing that can be said is that it interrupts (even if its sense were plain) the natural connexion between 165–7 and 170; the question of the expansion (in this case at any rate skilful and not inapt) of Hrothgar’s giedd, 1724–60; and most notably lines 175–88.

35 Of course the use of words more or less equivalent to ‘fate’ continued throughout the ages. The most Christian poets refer to wyrd, usually of unfortunate events; but sometimes of good, as in Elene 1047, where the conversion of Judas is ascribed to wyrd. There remains always the main mass of the workings of Providence (Metod) which are inscrutable, and for practical purposes dealt with as ‘fate’ or ‘luck’. Metod is in Old English the word that is most nearly allied to ‘fate’, although employed as a synonym of god. That it could be so employed is due probably to its having anciently in English an agental significance (as well as an abstract sense), as in Old Norse where mjōtuðr has the senses ‘dispenser, ruler’ and ‘doom, fate, death’. But in Old English metodsceaft means ‘doom’ or ‘death’. Cf. 2814 f. where wyrd is more active than metodsceaft. In Old Saxon metod is similarly used, leaning also to the side of the inscrutable (and even hostile) aspects of the world’s working. Gabriel in the Hêliand says of John the Baptist that he will not touch wine: so habed im uurdgiscapu, metod gimarcod endi maht godes (128); it is said of Anna when her husband died: that sie thiu mikila maht metodes todelda, uured uurdigiscapu (511). In Old Saxon metod(o)giscapu and metodigisceft, equal Fate, as O.E. metodsceaft.