Полная версия

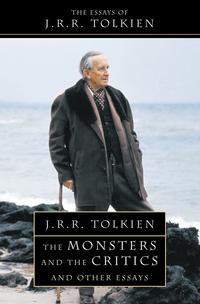

The Monsters and the Critics

Beowulf is not an ‘epic’, not even a magnified ‘lay’. No terms borrowed from Greek or other literatures exactly fit: there is no reason why they should. Though if we must have a term, we should choose rather ‘elegy’. It is an heroic-elegiac poem; and in a sense all its first 3,136 lines are the prelude to a dirge: him þa gegiredan Geata leode ad ofer eorðan unwaclicne: one of the most moving ever written. But for the universal significance which is given to the fortunes of its hero it is an enhancement and not a detraction, in fact it is necessary, that his final foe should be not some Swedish prince, or treacherous friend, but a dragon: a thing made by imagination for just such a purpose. Nowhere does a dragon come in so precisely where he should. But if the hero falls before a dragon, then certainly he should achieve his early glory by vanquishing a foe of similar order.

There is, I think, no criticism more beside the mark than that which some have made, complaining that it is monsters in both halves that is so disgusting; one they could have stomached more easily. That is nonsense. I can see the point of asking for no monsters. I can also see the point of the situation in Beowulf. But no point at all in mere reduction of numbers. It would really have been preposterous, if the poet had recounted Beowulf’s rise to fame in a ‘typical’ or ‘commonplace’ war in Frisia, and then ended him with a dragon. Or if he had told of his cleansing of Heorot, and then brought him to defeat and death in a ‘wild’ or ‘trivial’ Swedish invasion! If the dragon is the right end for Beowulf, and I agree with the author that it is, then Grendel is an eminently suitable beginning. They are creatures, feond mancynnes, of a similar order and kindred significance. Triumph over the lesser and more nearly human is cancelled by defeat before the older and more elemental. And the conquest of the ogres comes at the right moment: not in earliest youth, though the nicors are referred to in Beowulf’s geogoðfeore as a presage of the kind of hero we have to deal with; and not during the later period of recognized ability and prowess;32 but in that first moment, which often comes in great lives, when men look up in surprise and see that a hero has unawares leaped forth. The placing of the dragon is inevitable: a man can but die upon his death-day.

I will conclude by drawing an imaginary contrast. Let us suppose that our poet had chosen a theme more consonant with ‘our modern judgement’; the life and death of St Oswald. He might then have made a poem, and told first of Heavenfield, when Oswald as a young prince against all hope won a great victory with a remnant of brave men; and then have passed at once to the lamentable defeat of Oswestry, which seemed to destroy the hope of Christian Northumbria; while all the rest of Oswald’s life, and the traditions of the royal house and its feud with that of Deira might be introduced allusively or omitted. To any one but an historian in search of facts and chronology this would have been a fine thing, an heroic-elegiac poem greater than history. It would be much better than a plain narrative, in verse or prose, however steadily advancing. This mere arrangement would at once give it more significance than a straightforward account of one king’s life: the contrast of rising and setting, achievement and death. But even so it would fall far short of Beowulf. Poetically it would be greatly enhanced if the poet had taken violent liberties with history and much enlarged the reign of Oswald, making him old and full of years of care and glory when he went forth heavy with foreboding to face the heathen Penda: the contrast of youth and age would add enormously to the original theme, and give it a more universal meaning. But even so it would still fall short of Beowulf. To match his theme with the rise and fall of poor ‘folk-tale’ Beowulf the poet would have been obliged to turn Cadwallon and Penda into giants and demons. It is just because the main foes in Beowulf are inhuman that the story is larger and more significant than this imaginary poem of a great king’s fall. It glimpses the cosmic and moves with the thought of all men concerning the fate of human life and efforts; it stands amid but above the petty wars of princes, and surpasses the dates and limits of historical periods, however important. At the beginning, and during its process, and most of all at the end, we look down as if from a visionary height upon the house of man in the valley of the world. A light starts – lixte se leoma ofer landa fela – and there is a sound of music; but the outer darkness and its hostile offspring lie ever in wait for the torches to fail and the voices to cease. Grendel is maddened by the sound of harps.

And one last point, which those will feel who to-day preserve the ancient pietas towards the past: Beowulf is not a ‘primitive’ poem; it is a late one, using the materials (then still plentiful) preserved from a day already changing and passing, a time that has now for ever vanished, swallowed in oblivion; using them for a new purpose, with a wider sweep of imagination, if with a less bitter and concentrated force. When new Beowulf was already antiquarian, in a good sense, and it now produces a singular effect. For it is now to us itself ancient; and yet its maker was telling of things already old and weighted with regret, and he expended his art in making keen that touch upon the heart which sorrows have that are both poignant and remote. If the funeral of Beowulf moved once like the echo of an ancient dirge, far-off and hopeless, it is to us as a memory brought over the hills, an echo of an echo. There is not much poetry in the world like this; and though Beowulf may not be among the very greatest poems of our western world and its tradition, it has its own individual character, and peculiar solemnity; it would still have power had it been written in some time or place unknown and without posterity, if it contained no name that could now be recognized or identified by research. Yet it is in fact written in a language that after many centuries has still essential kinship with our own, it was made in this land, and moves in our northern world beneath our northern sky, and for those who are native to that tongue and land, it must ever call with a profound appeal – until the dragon comes.

APPENDIX

(a) Grendel’s Titles

The changes which produced (before A.D. 1066) the mediaeval devil are not complete in Beowulf, but in Grendel change and blending are, of course, already apparent. Such things do not admit of clear classifications and distinctions. Doubtless ancient pre-Christian imagination vaguely recognized differences of ‘materiality’ between the solidly physical monsters, conceived as made of the earth and rock (to which the light of the sun might return them), and elves, and ghosts or bogies. Monsters of more or less human shape were naturally liable to development on contact with Christian ideas of sin and spirits of evil. Their parody of human form (earmsceapen on weres wœstmum) becomes symbolical, explicitly, of sin, or rather this mythical element, already present implicit and unresolved, is emphasized: this we see already in Beowulf, strengthened by the theory of descent from Cain (and so from Adam), and of the curse of God. So Grendel is not only under this inherited curse, but also himself sinful: manscaða, synscaða, synnum beswenced; he is fyrena hyrde. The same notion (combined with others) appears also when he is called (by the author, not by the characters in the poem) hœþen, 852, 986, and helle hœfton,feond on helle. As an image of man estranged from God he is called not only by all names applicable to ordinary men, as wer, rinc, guma, maga, but he is conceived as having a spirit, other than his body, that will be punished. Thus alegde hœþene sawle: þœr him hel onfeng, 852; while Beowulf himself says ðœr abidan sceal miclan domes, hu him scir Metod scrifan wille, 978.

But this view is blended or confused with another. Because of his ceaseless hostility to men, and hatred of their joy, his super-human size and strength, and his love of the dark, he approaches to a devil, though he is not yet a true devil in purpose. Real devilish qualities (deception and destruction of the soul), other than those which are undeveloped symbols, such as his hideousness and habitation in dark forsaken places, are hardly present. But he and his mother are actually called deofla, 1680; and Grendel is said when fleeing to hiding to make for deofla gedrœg. It should be noted that feond cannot be used in this question: it still means ‘enemy’ in Beowulf, and is for instance applicable to Beowulf and Wiglaf in relation to the dragon. Even feond on helle, 101, is not so clear as it seems (see below); though we may add wergan gastes, 133, an expression for ‘devil’ later extremely common, and actually applied in line 1747 to the Devil and tempter himself. Apart, however, from this expression little can be made of the use of gast, gœst. For one thing it is under grave suspicion in many places (both applied to Grendel and otherwise) of being a corruption of gœst, gest ‘stranger’; compare Grendel’s title cwealmcuma, 792 = wœlgœst, 1331, 1995. In any case it cannot be translated either by the modern ghost or spirit. Creature is probably the nearest we can now get. Where it is genuine it applies to Grendel probably in virtue of his relationship or similarity to bogies (scinnum ond scuccum), physical enough in form and power, but vaguely felt as belonging to a different order of being, one allied to the malevolent ‘ghosts’ of the dead. Fire is conceived as a gœst (1123).

This approximation of Grendel to a devil does not mean that there is any confusion as to his habitation. Grendel was a fleshly denizen of this world (until physically slain). On helle and helle (as in helle gast 1274) mean ‘hellish’, and are actually equivalent to the first elements in the compounds deaþscua, sceadugengea, helruna. (Thus the original genitive helle developed into the Middle English adjective helle, hellene ‘hellish’, applicable to ordinary men, such as usurers; and even feond on helle could be so used. Wyclif applies fend on helle to the friar walking in England as Grendel in Denmark.) But the symbolism of darkness is so fundamental that it is vain to look for any distinction between the þystru outside Hrothgar’s hall in which Grendel lurked, and the shadow of Death, or of hell after (or in) Death.

Thus in spite of shifting, actually in process (intricate, and as difficult as it is interesting and important to follow), Grendel remains primarily an ogre, a physical monster, whose main function is hostility to humanity (and its frail efforts at order and art upon earth). He is of the fifelcyn, a þyrs or eoten; in fact the eoten, for this ancient word is actually preserved in Old English only as applied to him. He is most frequently called simply a foe: feond, lað, sceaða, feorhgeniðla, laðgeteona, all words applicable to enemies of any kind. And though he, as ogre, has kinship with devils, and is doomed when slain to be numbered among the evil spirits, he is not when wrestling with Beowulf a materialized apparition of soul-destroying evil. It is thus true to say that Grendel is not yet a real mediaeval devil – except in so far as mediaeval bogies themselves had failed (as was often the case) to become real devils. But the distinction between a devilish ogre, and a devil revealing himself in ogre-form – between a monster, devouring the body and bringing temporal death, that is inhabited by an accursed spirit, and a spirit of evil aiming ultimately at the soul and bringing eternal death (even though he takes a form of visible horror, that may bring and suffer physical pain) – is a real and important one, even if both kinds are to be found before and after 1066. In Beowulf the weight is on the physical side: Grendel does not vanish into the pit when grappled. He must be slain by plain prowess, and thus is a real counterpart to the dragon in Beowulf’s history.

(Grendel’s mother is naturally described, when separately treated, in precisely similar terms: she is wif, ides, aglœc wif; and rising to the inhuman: merewif, brimwylf, grundwyrgen. Grendel’s title Godes andsaca has been studied in the text. Some titles have been omitted: for instance those referring to his outlawry, which are applicable in themselves to him by nature, but are of course also fitting either to a descendant of Cain, or to a devil: thus heorowearh, dœdhata, mearcstapa, angengea.)

(b) ‘Lof’ and ‘Dom’; ‘Hell’ and ‘Heofon’

Of pagan ‘belief’ we have little or nothing left in English. But the spirit survived. Thus the author of Beowulf grasped fully the idea of lof or dom, the noble pagan’s desire for the merited praise of the noble. For if this limited ‘immortality’ of renown naturally exists as a strong motive together with actual heathen practice and belief, it can also long outlive them. It is the natural residuum when the gods are destroyed, whether unbelief comes from within or from without. The prominence of the motive of lof in Beowulf – long ago pointed out by Earle – may be interpreted, then, as a sign that a pagan time was not far away from the poet, and perhaps also that the end of English paganism (at least among the noble classes for whom and by whom such traditions were preserved) was marked by a twilight period, similar to that observable later in Scandinavia. The gods faded or receded, and man was left to carry on his war unaided. His trust was in his own power and will, and his reward was the praise of his peers during his life and after his death.

At the beginning of the poem, at the end of the first section of the exordium, the note is struck: lofdœdum sceal in mœgþa gehwœre man geþeon. The last word of the poem is lofgeornost, the summit of the praise of the dead hero: that was indeed lastworda betst. For Beowulf had lived according to his own philosophy, which he explicitly avowed: ure œghwylc sceal ende gebidan worolde lifes; wyrce se ðe mote domes œr deaþe: þœt bið dryhtguman æfter selest, 1386 ff. The poet as commentator recurs again to this: swa sceal man don, þonne he æt guðe gegan þenceð longsumne lof: na ymb his lif cearað, 1534 ff.

Lof is ultimately and etymologically value, valuation, and so praise, as we say (itself derived from pretium). Dom is judgement, assessment, and in one branch just esteem, merited renown. The difference between these two is not in most passages important. Thus at the end of Widsith, which refers to the minstrel’s part in achieving for the noble and their deeds the prolonged life of fame, both are combined: it is said of the generous patron, lof se gewyrceð, hafað under heofonum heahfœstne dom. But the difference has an importance. For the words were not actually synonymous, nor entirely commensurable. In the Christian period the one, lof, flowed rather into the ideas of heaven and the heavenly choirs; the other, dom, into the ideas of the judgement of God, the particular and general judgements of the dead.

The change that occurs can be plainly observed in The Seafarer, especially if lines 66–80 of that poem are compared with Hrothgar’s giedd or sermon in Beowulf from 1755 onwards. There is a close resemblance between Seafarer 66–71 and Hrothgar’s words 1761–8, a part of his discourse that may certainly be ascribed to the original author of Beowulf, whatever revision or expansion the speech may otherwise have suffered. The Seafarer says:

ic gelyfe no

þœt him eorðwelan ece stondað.

Simle þreora sum þinga gehwylce

œr his tid[d]ege to tweon weorþeð:

adl oþþe yldo oþþe ecghete

fœgum fromweardum feorh oðþringeð.

Hrothgar says:

oft sona bið

þœt þec adl oððe ecg eafoþes getwœfeð,

oððe fyres feng, oððe flodes wylm,

oððe gripe meces, oððe gares fliht,

oððe atol yldo; oððe eagena bearhtm

forsiteð ond forsworceð. Semninga bið

þœt þec, dryhtguma, deað oferswyðeð.

Hrothgar expands þreora sum on lines found elsewhere, either in great elaboration as in the Fates of Men, or in brief allusion to this well-known theme as in The Wanderer 80 ff. But the Seafarer, after thus proclaiming that all men shall die, goes on: ‘Therefore it is for all noble men lastworda betst (the best memorial), and praise (lof) of the living who commemorate him after death, that ere he must go hence, he should merit and achieve on earth by heroic deeds against the malice of enemies (feonda), opposing the devil, that the children of men may praise him afterwards, and his lof may live with the angels for ever and ever, the glory of eternal life, rejoicing among the hosts.’

This is a passage which from its syntax alone may with unusual certainty be held to have suffered revision and expansion. It could easily be simplified. But in any case it shows a modification of heathen lof in two directions: first in making the deeds which win lof resistance to spiritual foes – the sense of the ambiguous feonda is, in the poem as preserved, so defined by deofle togeanes; secondly, in enlarging lof to include the angels and the bliss of heaven. lofsong, loftsong are in Middle English especially used of the heavenly choirs.

But we do not find anything like this definite alteration in Beowulf. There lof remains pagan lof, the praise of one’s peers, at best vaguely prolonged among their descendants awa to ealdre. (On soðfœstra dom, 2820, see below.) In Beowulf there is hell: justly the poet said of the people he depicted helle gemundon on modsefan. But there is practically no clear reference to heaven as its opposite, to heaven, that is, as a place or state of reward, of eternal bliss in the presence of God. Of course heofon, singular and plural, and its synonyms, such as rodor, are frequent; but they refer usually either to the particular landscape or to the sky under which all men dwell. Even when these words are used with the words for God, who is Lord of the heavens, such expressions are primarily parallels to others describing His general governance of nature (e.g. 1609 ff.), and His realm which includes land and sea and sky.

Of course it is not here maintained – very much the contrary – that the poet was ignorant of theological heaven, or of the Christian use of heofon as the equivalent of caelum in Scripture: only that this use was of intention (if not in practice quite rigidly) excluded from a poem dealing with the pagan past. There is one clear exception in lines 186 ff: wel bið þœm þe mot œfter deaðdœge Drihten secean, ond to Fœder fœþmum freoðo wilnian. If this, and the passage in which it occurs, is genuine – descends, that is, without addition or alteration from the poet who wrote Beowulf as a whole – and is not, as, I believe, a later expansion, then the point is not destroyed. For the passage remains still definitely an aside, an exclamation of the Christian author, who knew about heaven, and expressly denied such knowledge to the Danes. The characters within the poem do not understand heaven, or have hope of it. They refer to hell – an originally pagan word.33 Beowulf predicts it as the destiny of Unferth and Grendel. Even the noble monotheist Hrothgar – so he is drawn, quite apart from the question of the genuineness of the bulk of his sermon from 1724–60 – refers to no heavenly bliss. The reward of virtue which he foretells for Beowulf is that his dom shall live awa to ealdre, a fortune also bestowed upon Sigurd in Norse (that his name œ mun uppi). This idea of lasting dom is, as we have seen, capable of being christianized; but in Beowulf it is not christianized, probably deliberately, when the characters are speaking in their proper persons, or their actual thoughts are reported.

The author, it is true, says of Beowulf that him of hreðre gewat sawol secean soðfœstra dom. What precise theological view he held concerning the souls of the just heathen we need not here inquire. He does not tell us, saying simply that Beowulf’s spirit departed to whatever judgement awaits such just men, though we may take it that this comment implies that it was not destined to the fiery hell of punishment, being reckoned among the good. There is in any case here no doubt of the transmutation of words originally pagan. soðfœstra dom could by itself have meant simply the ‘esteem of the true-judging’, that dom which Beowulf as a young man had declared to be the prime motive of noble conduct; but here combined with gewat secean it must mean either the glory that belongs (in eternity) to the just, or the judgement of God upon the just. Yet Beowulf himself, expressing his own opinion, though troubled by dark doubts, and later declaring his conscience clear, thinks at the end only of his barrow and memorial among men, of his childlessness, and of Wiglaf the sole survivor of his kindred, to whom be bequeaths his arms. His funeral is not Christian, and his reward is the recognized virtue of his kingship and the hopeless sorrow of his people.

The relation of the Christian and heathen thought and diction in Beowulf has often been misconceived. So far from being a man so simple or so confused that he muddled Christianity with Germanic paganism, the author probably drew or attempted to draw distinctions, and to represent moods and attitudes of characters conceived dramatically as living in a noble but heathen past. Though there are one or two special problems concerning the tradition of the poem and the possibility that it has here and there suffered later unauthentic retouching,34 we cannot speak in general either of confusion (in one poet’s mind or in the mind of a whole period), or of patch-work revision producing confusion. More sense can be made of the poem, if we start rather with the hypothesis, not in itself unlikely, that the poet tried to do something definite and difficult, which had some reason and thought behind it, though his execution may not have been entirely successful.

The strongest argument that the actual language of the poem is not in general the product either of stupidity or accident is to be found in the fact that we can observe differentiation. We can, that is, in this matter of philosophy and religious sentiment distinguish, for instance: (a) the poet as narrator and commentator; (b) Beowulf; and (c) Hrothgar. Such differentiation would not be achieved by a man himself confused in mind, and still less by later random editing. The kind of thing that accident contrives is illustrated by drihten wereda, ‘lord of hosts’, a familiar Christian expression, which appears in line 2186, plainly as an alteration of drihten Wedera ‘lord of the Geats’. This alteration is obviously due to some man, the actual scribe of the line or some predecessor, more familiar with Dominus Deus Sabaoth than with Hrethel and the Weder-Geatish house. But no one, I think, has ventured to ascribe this confusion to the author.

That such differentiation does occur, I do not attempt here to prove by analysis of all the relevant lines of the poem. I leave the matter to those who care to go through the text, only insisting that it is essential to pay closer attention than has usually been paid to the circumstances in which the references to religion, Fate, or mythological matters each appear, and to distinguish in particular those things which are said in oratio recta by one of the characters, or are reported as being said or thought by them. It will then be seen that the narrating and commenting poet obviously stands apart. But the two characters who do most of the speaking, Beowulf and Hrothgar, are also quite distinct. Hrothgar is consistently portrayed as a wise and noble monotheist, modelled largely it has been suggested in the text on the Old Testament patriarchs and kings; he refers all things to the favour of God, and never omits explicit thanks for mercies. Beowulf refers sparingly to God, except as the arbiter of critical events, and then principally as Metod, in which the idea of God approaches nearest to the old Fate. We have in Beowulf’s language little differentiation of God and Fate. For instance, he says gœð a wyrd swa hio scel and immediately continues that dryhten holds the balance in his combat (441); or again he definitely equates wyrd and metod (2526 f.).35 It is Beowulf who says wyrd oft nereð unfœgne eorl, þonne his ellen deah (immediately after calling the sun beacen Godes), which contrasts with the poet’s own comment on the man who escaped the dragon (2291): swa mœg unfœge eaðe gedigean wean ond wrœcsið, se ðe Wealdendes hyldo gehealdeþ. Beowulf only twice explicitly thanks God or acknowledges His help: in lines 1658–61, where he acknowledges God’s protection and the favour of ylda Waldend in his combat under the water; in his last speech, where he thanks Frean Wuldurcyninge … ecum Dryhtne for all the treasure, and for helping him to win it for his people. Usually he makes no such references. He ascribes his conquest of the nicors to luck – hwœþre me gesœlde, 570 ff. (compare the similar words used of Sigemund, 890). In his account to Hygelac his only explanation of his preservation in the water-den is nœs ic fœge þa gyt (2141). He does not allude to God at all in this report.