Полная версия

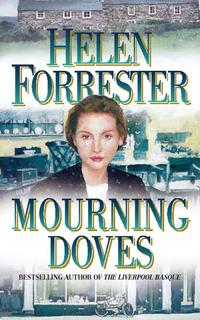

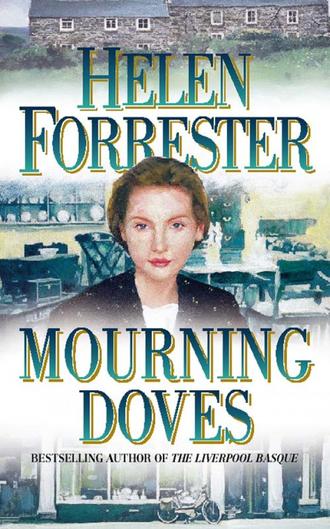

Mourning Doves

Looking down at the smelly garments, she realised dully that she did not know how to wash clothes properly, and she wondered if they would be able to employ a washerwoman. Even during the war, when they had had to manage the house with only Winnie living in, they had been able to find women to do the washing and clean the house; they were usually army privates’ wives, living on very small army pay, who had children whom they did not want to leave alone for long. They had been thankful to come in by the day to earn an extra few shillings.

As she washed herself in the sink of the jewel of her mother’s house, the bathroom, which glittered with white porcelain and highly polished mahogany, she remembered the earth lavatory of the cottage. Such primitive sanitary arrangements meant that they must take with them the old-fashioned washstands with their attendant china basins, jugs, buckets and chamber pots; she recollected that three rooms in their present home were still equipped with these pieces of furniture. And there was a tin bath in the cellar – they would need that, with all the work that it implied – heating and carrying jugs of hot water upstairs to a bedroom, and afterwards bringing down the dirty water, not to speak of the dragging up and down of the bath itself, all chores that she herself would probably have to attend to.

While she brushed her hair and then tied it into a neat knot to be pinned at the back of her neck, she wondered resentfully whether, in addition to all the usual jobs her mother expected her to do, she was going to spend her whole future trying to deal with the domestic problems of the cottage.

Later, when she was dressed, the last button of a clean black blouse done up and a black bow tied under her chin, she paused to look at herself in the mirror, and made a wry face. She looked pinched and old. She was drained by the fears besetting her, acutely aware of her own ignorance. Even Ethel, struggling to make the fire go in the breakfast room, was not as helpless as she was. At least Ethel could make a fire and could probably cook a meal on it if she had to.

Why haven’t I learned to cook? she asked herself dully. Or even watched Mrs Walls, when she comes in on Mondays to do the washing? Or looked to see in what order Dorothy does the rooms, so that she doesn’t redistribute the dust? And as for making the cottage garden look decent, I don’t know how to begin.

The answer was clear to her. As a single, upper middle-class lady, she was not expected to know. Her job was to run after her mother, be her patient companion, carry her parcels, find her glasses, help her choose library books in the Argosy Library, make a fourth player at cards if no one else was available, write invitations and thank-you notes – and be careful always to be pleasant and never give offence to men, particularly to her father. And when her parents were gone, she would probably do the same for Edna – tolerated in her brother-in-law’s house, either because Edna had begged a roof for her or, on Paul’s part, from a faint sense of duty to a penniless woman.

‘I wish I were dead,’ she hissed tearfully at the reflection in the wardrobe mirror, and went down to the breakfast room to find a pencil and make a list.

Chapter Seven

While Dorothy and Ethel finished cleaning the breakfast room, Celia, list in hand, went down to the basement to talk to Winnie.

On seeing her young mistress, the cook hastily rose from eating her own breakfast at the kitchen table. With the corner of her white apron, she surreptitiously dabbed the corners of her mouth.

‘Don’t get up, Winnie. Finish your breakfast. I just thought I’d have a word with you, before Mother rings for her tray.’

Winnie sank slowly back into her chair and picked up her fork again. She looked cautiously at Celia, who had walked over to the kitchen dresser and taken down a cup and saucer. The girl looked as if she were on the point of collapse.

‘Would you be liking a cup of tea, Miss?’

Celia laid the cup and saucer down in front of the cook, and then pulled out another kitchen chair to sit down on. ‘Yes, please, if you can spare it from your pot.’

‘To be sure, Miss.’

While Celia slowly sipped a very strong cup of tea and Winnie finished up her egg and fried bread, both women basked in the warmth of the big fire in the kitchen range. Ethel had made it ready in anticipation of Winnie’s beginning the serious cooking of the day as soon as she had finished her own meal.

The heat was very comforting, and some of Celia’s jitteriness left her. ‘I was wondering, Winnie,’ she began, ‘if one of you could come out to the Meols cottage with me and help me clean it. I think it will take more than one day. Could two of you manage, here, to look after Mother? I think I may have to be quick about making arrangements, and we can’t move anything from this house until the other one is clean. Mr Billings, the agent, will be going out there today to make sure it is watertight.’

At the reminder of the impending demise of the household, poor Winnie’s breast heaved under her blue and white striped dress. Her response, however, showed no resentment. She said helpfully, ‘Oh, aye, Miss. Our Dorothy would be the best one to take – and you’d need to get the chimneys swept, no doubt.’ She paused and ran her tongue round her teeth, to rid them of bits of egg, while she considered the situation. ‘Anybody living nearby will put you on to a sweep, I’m sure. And you’d have to take brooms and brushes – and dusters and polish with you, wouldn’t you?’

In twenty minutes, Winnie had a cleaning campaign worked out. She inquired whether the water in the house was turned on.

Feeling a little ashamed at how low they had sunk, Celia admitted that there was only a pump that did not work and a well of uncertain cleanliness. She said hopefully, ‘I think Mr Fairbanks from next door would let us take water from his pump for a day or two. He’s very nice.’

‘Would he? That would be proper kind. A friendly neighbour’s worth a lot.’ Winnie heaved herself out of her chair and began to clear the table. ‘You’d better get a plumber to fix the pump, hadn’t you? You could ask him what to do about the well. He’ll know – and I’ll put together some lunch for you.’

Celia began to feel that her life was regaining some sense of order, and she looked gratefully at the cook. ‘You’re wonderful, Winnie,’ she said with feeling, as she took her empty teacup to the kitchen sink ready for Ethel when she came down to the basement kitchen to do the washing up.

At that moment, Dorothy, carrying her brooms, bucket, dustpan and brush, and carpet sweeper, pushed open the kitchen door. She was bent on snatching her breakfast before she had to serve Louise and Celia their meal. Winnie told her immediately that she would be spending the next day in Meols, cleaning Miss Celia’s new home.

Dorothy opened her mouth to protest, and then decided that it might be a bit of a change. She nodded assent, and said, ‘Yes, Miss,’ to Celia very primly, as if being whisked out to Meols was something that happened regularly to her. Then she hung up her dustpan and brush in a cupboard, and picked up the carpet sweeper again to take it outside to empty it into the dustbin. She unlocked the heavy back door and trotted into the brick-lined area outside.

As she opened the flaps of the carpet sweeper and shook out the dust, she could hear, very distantly, Ethel singing ‘The Roses of Picardy’, as she scrubbed the front steps, and she began to regret her agreement to go out to Meols. Out there, it would likely be scrubbing, scrubbing all the way, she considered sourly, as she clicked the sweeper shut. Why hadn’t she suggested that Miss should take Ethel instead?

Before leaving the kitchen, Celia turned and gave the cook a quick hug. ‘I don’t know what we’re going to do without you,’ she said.

Winnie forced a smile, and wondered what she was going to do without the Gilmore family, whom she had served for over fifteen years. All through the war, I stayed with them, she considered dolefully, when I could have earned much more in a munitions factory – I was proper stupid. I could have saved something to help me now.

A bell in the corner of the kitchen rang, and she turned to see which one it was. ‘Your mam’s awake,’ she shouted after Celia, who was running up the kitchen stairs. ‘Will you tell me when she’s ready for her breakfast?’

‘I will.’

As Celia went up the second staircase to her mother’s bedroom, she smiled slightly. Things were already changing. Winnie would never have referred to her mother as ‘your mam’ if her father had been alive; and, at the sound of the bell, Dorothy would have had to climb the two staircases to inquire directly what it was that Madam required.

Considering her flood of tears the previous night, Louise managed a remarkably solid breakfast. Celia, who did not want any, sat on the bed beside her, patiently wondering how to discuss their problems with her without causing yet another collapse into tears.

Finally, Louise laid her empty cup down on its saucer, and sighed. ‘Put the tray on the side table for me, dear,’ she ordered.

Celia did as she was bidden, while Louise crossed her hands over her stomach and stared disconsolately out of the window at a fine March day. She took no notice when Celia pulled out of her skirt pocket the list she had made earlier.

‘Mother,’ she said tentatively, ‘because Cousin Albert thinks we may have to move quickly from here, I’ve made a rough list of what I think we must do at once.’

Her mother turned to look at her, her pale, slightly protruding blue eyes showing no sign of tears. There was, however, a total absence of expression in them, and Celia wondered if her mother was feeling the same sense of unreality that she was, as if she were a long way off from what was happening, that this wasn’t her life at all; she was merely watching a play.

‘Yes, dear?’ Louise’s voice was quite calm, though she sounded weary.

Celia gathered her wandering thoughts, and began by saying, ‘I thought we’d better see, first, how much money we have access to.’ She paused, feeling that it was vulgar to consider money when they had just been bereaved. But they had to live until the house was sold, so she added firmly, ‘I suppose that dear Papa gave you the housekeeping at the beginning of the month?’

Louise gave a sobbing sigh, and said, ‘Yes, dear. I hope I can make it last through the first week in April.’

‘Then there’s the cheque Mr Billings gave you yesterday. How do we get money for it? Do you know?’

‘Your dear father always paid it into my bank account, and when I wanted to pay for a special dress, or something, for either you or me – or gifts – personal things, I wrote a cheque. I’m sure Mr Carruthers would show us how to put Mr Billings’ cheque into my account.’

‘Is there anything in the account at present?’

‘I don’t think so, dear. Your dear father got me to write a cheque on it for him about three months ago. It was a loan.’

Celia felt an uncomfortable qualm in her stomach at this disclosure. She wondered what else her father might have done, which would further imperil their limited finances. She suggested that if Louise felt strong enough they should pay a call on the bank that afternoon, to which Louise agreed.

‘Did Papa have a solicitor for his affairs, Mama?’

‘Well, he had Mr Barnett, of course, who came to the funeral, dear. As far as I know, he did any legal work in connection with your father’s business. He’s supposed to be supervising the sale of this house, remember?’ Louise moved restlessly in her bed. ‘But Father didn’t use his services very much, because he was expensive. He even wrote his will himself; but Cousin Albert says that it is perfectly valid. He said it was witnessed by Andy McDougall and his chief clerk.’

Celia knew of old Mr McDougall. When he had attended the funeral, he had looked as ferocious as his reputation held him to be, and with him there had been another old gentleman, who could well have been his chief clerk. She recollected vaguely that he was a corn merchant and had a small office, similar to her father’s, in the same building. She had noticed Cousin Albert talking with them after the funeral, probably because, as Albert had told her, he needed, first, to satisfy himself of the authenticity of the witnesses’ signatures to the will.

‘Do we need a solicitor, Celia?’ The question held a hint of anxiety in it.

Celia chewed her lower lip. ‘I don’t really know, Mama,’ she confessed. ‘But this house belongs to you – and it’s a handsome house – it must be worth quite a lot.’ How could she say that she did not trust her father’s cousin very much – she had no real reason to feel like this, except that he was being very domineering and he had apparently tried to collect the rents which Mr Billings had refused to hand over to him.

She said slowly, ‘I think that you should have a legal man to make sure that you receive what is yours.’

Her mother gave a small shocked gasp, and Celia hastily added, ‘Well, laws are funny things, and it is difficult for us to know what we are signing – we can read it – but understanding is something different. Did you understand the papers that you signed for Mr Barnett and the estate agent the other day?’

Louise was frightened. ‘Not really; they both said they gave them permission to sell the house and for the agent to charge me a commission for doing it. Should I have had a solicitor of my own? Albert said I should sign – and he was once a solicitor himself.’ She looked helplessly up at Celia.

‘Try not to worry, Mama. The papers probably are all right.’ How could she say to her mother that it was Albert Gilmore himself about whom she felt doubtful? She finally replied carefully, ‘I know he was a solicitor. But he’s looking after the will – which is Father’s affair. You don’t have anybody. Perhaps there should be someone who is interested only in your affairs.’

‘Yes, dear. I see.’ Louise was trembling with apprehension as she began slowly to get out of bed. Her huge, lace-trimmed cotton nightgown caught in the bedclothes, and momentarily a fine pair of snow-white legs were exposed to the spring sunlight pouring through the windows.

She hastily hitched her gown more modestly round her, but not before Celia had the sudden realisation that, though her mother always appeared old to her and her face petulant, she was extremely well preserved, with a perfect skin and luxuriant hair.

She might marry again. And, if she did, where would I be? she asked herself fearfully.

She swallowed hard. She had enough to worry about without anything else.

She said carefully, as she moved out of Louise’s way, ‘Perhaps Mr Carruthers at the bank could recommend a solicitor to us. We could ask him.’

As Louise nodded agreement, they both heard the front door bell faintly tinkling in the kitchen.

‘I think that will be Phyllis. She left her card yesterday when we were out, and said she would come again today. There are some cards on the tray for you, too. Will you be all right, Mother, if I go down? We could walk round to the bank this afternoon. Phyllis won’t stay long.’

Louise was already on her way to the bathroom and in the distance they could hear Dorothy running across the hall to answer the front door. Over her shoulder, Louise agreed resignedly, and then said in a more normal voice, ‘Really, Phyllis should not be walking out in her condition.’

‘Times have changed, Mother. Ladies-in-waiting go about a lot more than they used to do.’

‘A true gentlewoman would not!’ The remark sounded so much more like her mother’s usual disapproval of Phyllis that Celia was quite relieved. Louise had disapproved of Phyllis ever since she had first appeared at the front door, when she was nine years old, to ask if Celia could come out to play hopscotch. In Louise’s opinion, the daughter of a carriage builder – a tradesman – was no companion for the granddaughter of a baronet and daughter of a prominent businessman in commerce. The girls had, however, clung to each other. Both were lonely and shy, great bookworms, and were over-protected – Phyllis because she was a precious only child and Celia because she was to be kept at home as a companion-help. Neither was allowed to mix very much with other children.

Celia let her mother cross the passage to the bathroom, and then ran lightly down the stairs, to be enveloped – as far as was possible – in her friend’s arms.

Chapter Eight

With a toddler clinging to her hand, Phyllis greeted her friend tenderly. ‘I’m so sad for you and for Mrs Gilmore. It must be terrible for you.’

‘Thank you, dear. How are you?’

The inquiry did not need a reply. Phyllis was her usual untidy self. Her hair below her wide-brimmed beige hat was threatening to fall down her back at any minute, and her face was drained of colour, except for black rings round her tired eyes. Her long black skirt, which had dog hairs on it, half-covered her swollen ankles. To disguise her pregnancy, she wore an out-of-fashion cheviot cape of her mother’s which barely met across her swollen stomach.

Phyllis simply grimaced in response to Celia’s mechanical inquiry, and then shrugged as if to convey that her well-being was of no consequence.

Celia went down on her knees to ask the toddler, ‘And how’s little Eric today?’

Eric turned away from her and buried his grubby, marmalade-smeared face in his mother’s skirt. Celia smiled and patted his flaxen head as she got up again.

‘Come into the breakfast room. There’s a good fire there. Dorothy hasn’t done the sitting room yet.’

Phyllis sighed with relief as she sank into Louise’s favourite chair. It was upholstered in faded green velveteen and was armless, which allowed space for the stout or pregnant to spread their skirts comfortably around them. She remarked with feeling, ‘I shall be thankful when my little burden arrives.’

‘It can’t be long now, can it?’ Celia asked. Though Phyllis had explained to her how dreadfully vulgar were the things a husband did to you which led to having a baby, Celia had never liked to inquire how long it took the baby to grow.

‘Any time now, the midwife thinks. This morning she advised that I should stay close to home.’ She shifted uneasily in her chair, and then went on, ‘You always get hours of warning, though, so I thought I should squeeze in a visit to you. You and Mrs Gilmore must be absolutely devastated.’

Celia nodded. She did not know how to explain what she was feeling, because after her little talk with Winnie in the basement kitchen she had sensed in herself a stirring of relief.

She had realised suddenly that she was not grieving for her father so much as she was upset at her own lack of competence in dealing with the disarray he had left behind him. He had been very hard to live with; and she had to admit that she had not, in the past week, missed his hectoring voice criticising some alleged fault in her behaviour.

To cover her confusion at Phyllis’s remark, she glanced round to check on little Eric.

She saw that he had discovered one of the household cats asleep on what had been Timothy Gilmore’s chair. He was nuzzling into the animal’s long black fur. It seemed to be tolerating him quite well, so she asked Phyllis if she was comfortable in the chair in which she was sitting. Having been assured ruefully that she was – as far as it was possible to be comfortable in her situation – Celia asked, ‘How many babies do you want to have, Phyllis?’

Phyllis laughed. She said cynically. ‘I don’t have any say in the matter. They simply come.’

‘Does it hurt?’

‘Yes – and it makes you so tired afterwards and you want to cry a lot. And husbands don’t like that, of course.’ Phyllis winced under her breath and straightened her back.

Celia drew a stool towards the fire, so that she could sit close to her friend. ‘Perhaps, when Mr Woodcock progresses in his career, you will be able to have a nanny as well as your maid?’ she suggested. She leaned forward to tug at the bell pull hanging beside the fireplace, to call Dorothy and ask her to bring some coffee.

Phyllis slowly drew off her black gloves, as she replied, ‘I hope so.’

Long ago, she had, when Celia had asked her, told her frankly the basic facts of sexual intercourse and that it was a right of a man to demand it of his wife. Poor Phyllis had gone into her marriage totally ignorant of what it implied, and had been so shocked and her husband so clumsy that she had never enjoyed it. She endured it as best she could – and the babies came, and her husband grew ever more irritable and hard to live with. Neither she nor Celia, therefore, had any idea that intercourse could be pleasurable. It was popular to coo over babies and forget what went beforehand.

Celia did not know the details of Phyllis’s marriage, but she did understand that her friend was worn out and unhappy, and she had long since begun to think that marriage was not quite the happy state that girls were told it was.

If one had an income of one’s own, she had considered, it would be pleasanter to remain single – except that one could not have a baby, and she herself would love to have just one, like little Eric.

Phyllis returned to the reason for her visit. ‘How is Mrs Gilmore?’ she asked.

‘She seems more herself this morning, a little less exhausted.’

‘I was horrified to see the For Sale notice on your gate. Does Mrs Gilmore really want to move?’

Even to Phyllis, Celia did not feel able to talk of financial problems; it was not the thing. So she said abruptly that the house was far too big and that they were going to renovate a summer cottage that they owned, in Meols. ‘The sea air, you know – Mother thinks it will be good for both of us. My Aunt Felicity left the place to Mother. Father didn’t like it, so it has been let for a number of years. It’s vacant now.’

Phyllis’s dejected expression lifted a little. ‘How lovely to be able to live by the sea,’ she responded longingly.

‘You’ll have to bring the family to visit us, once we’re settled in,’ Celia replied with a sudden glint of enthusiasm. ‘Sea air would do you a world of good.’ She suddenly saw an advantage to living in Meols. She could really give some relief to Phyllis by inviting her out for the day, with the children.

A sullen Dorothy arrived in response to the bell, and Celia told her to bring a pot of coffee and some biscuits and a glass of milk for Eric.

Celia’s ring had interrupted an anxious conning by Winnie and Dorothy of the Situations Vacant column in The Lady, a magazine devoted to the interests of middle-class families, which included a constant search for competent, cheap domestics.

Back in the kitchen, while she assembled the tray, Winnie glumly closed the magazine. ‘All the best jobs is in the south. Nothin’ up in the north here at all. We’d better look in the evening paper when it comes.’

‘Oh, aye,’ Dorothy agreed, as she quickly measured coffee beans into the grinder and turned the handle vigorously. ‘I were thinking I might try for a waitress’s job. You get tips then.’

‘That’s all right if you’ve got a home to go to. If you haven’t, you’ve got to find a room somewhere – and that’ll cost you.’

‘I suppose.’ Dorothy whisked the ground coffee into a pot and poured boiling water over it from the kettle kept simmering on the hob. She stirred the coffee and clapped the lid on the pot. Then, as she paused to let the grounds settle, she asked, ‘Do you know where the Missus is? I want to do her bedroom.’

‘Lying in her nice warm bath, I’ll be bound – and no hot water left for washing the tiles in the hall. You take the tray up, and I’ll put the big kettle on the fire again.’

‘Ta ever so.’

As Dorothy moved a small side table closer to Celia and then set the tray down on it, she took a quick look at Phyllis’s face. Very close to her time, she reckoned knowingly, and this was confirmed by Phyllis’s face suddenly puckering up as the ache in her back became sharper.