Полная версия

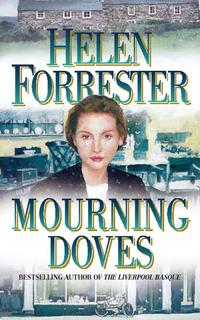

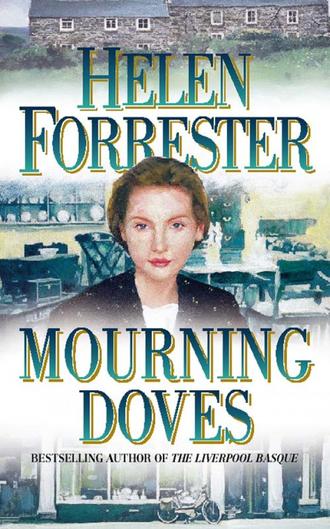

Mourning Doves

As he looked down at her, Louise’s silence did not seem to disconcert him in the least. His faded blue eyes held the hint of a smile, as he said, ‘You must be Mrs Gilmore. The gentleman as was here to take a quick look at the cottage for you said as you would be coming. He come out late Tuesday. Nearly dark, it was.’

A quiet rage against Cousin Albert rose in Louise, blotting out all sense of fear or grief. So, during his stay with her, he had not spent all his time in Timothy’s office checking over with the clerk just exactly what the financial situation was; he had also been out here, planning to condemn her to live in this awful place. He knew precisely what it was like.

With sudden understanding she realised how she had been manipulated. Albert and Mr Barnett had made her sign away her present home.

It was so unfair. They should have explained to her what she was about to do. Consulted her. The fact that the outcome would probably have been the same did not make any difference. She had not been asked what she felt about moving out here.

Could she not have sold this horrible cottage and bought another tiny house in a decent, civilised Liverpool street?

No time had been allowed her to recover from her bereavement, she raged; there had been no understanding that she was distraught with grief.

She was healthily furious, not only with Albert and Mr Barnett, but also with Timothy.

Timothy might have had enough sense to tell her that she owned their home, when he had originally transferred it.

Unless he had not trusted her? What a dreadful thought!

That was it. He must have felt, like Cousin Albert, that she was not capable of dealing with the ownership of such a valuable property; in transferring the ownership to her he must simply have been ensuring that no creditor of his could ever seize his home.

Men were like that, she felt with sudden, bitter understanding of the helplessness imposed on women.

She drew herself up to her full height, and replied frigidly to the stranger. ‘Yes, I am Mrs Timothy Gilmore.’

‘And the young lady?’

‘My daughter, Miss Celia Gilmore.’

The man smiled down at the tiny younger woman. Framed by untidy blonde hair, her face had the whiteness of skin never exposed to sunlight. Her loose, black-belted jacket and full skirt were relieved only by a white blouse. A tiny gold cross and chain glittered on a blue-white throat. A wide-brimmed black hat, worn squarely on her head, did nothing to improve her looks. A proper little mouse, her mam’s companion-help, he judged her, but probably amiable enough to be a good neighbour. ‘Nice to know yez, luv,’ he said warmly.

Celia smiled nervously in return. She sensed that the old man approved of her. It felt nice; she rarely got approval from anybody. As her mother’s patient shadow, she was usually barely noticed.

Their visitor pointed an arthritic finger at the house next door, and, as if taking it for granted that the ladies would be moving into the cottage they had just inspected, he said, ‘I’m your neighbour. Me name’s Eddie Fairbanks. Was head gardener to the earl till he sold the family home to be a nursing home for wounded soldiers. Proper kind to me, he was. Served him forty years I did, ever since I were a lad of ten, so I was close to retirement, anyway. He give me the cottage rent free for me lifetime and me wife’s lifetime – ’cos, he said, I designed one of the best rose gardens in the north for him, and he loved roses. He hoped the servicemen would enjoy the garden. He lives in London now.’ He paused to take a breath, while the two women stared at him. Since they did not say anything, he went on, ‘My Alice passed away six years ago, so I manage by meself.’ He paused again, as if expecting some response from Louise, but when there was none, he asked, ‘Would you like a cuppa tea? The kettle’s already hot. That house must’ve been cold when you went in – with the wind, and all.’

‘No, thank you,’ Louise replied stiffly. Tea with a gardener? What was she coming to?

Celia, however, caught her arm and, smiling unexpectedly prettily at the old man, she said, ‘Mother! It would be so nice to get acquainted with Mr Fairbanks. He might be able to tell us more than Mr Billings would.’

‘Ha! Old Billings?’ interjected Mr Fairbanks. ‘In Birkenhead, eh? He hasn’t taken much care of the place for you, has he?’

Celia replied ruefully, ‘No, not by the look of it.’ She turned her head to smile up at her mother. ‘A cup of tea would be lovely, Mother.’ She gave Louise’s arm a warning little tug. In their desperate situation, a male neighbour could be very helpful.

Louise was still inwardly steaming with rage, but out of courtesy she reluctantly agreed. She said to Mr Fairbanks, ‘Very well. It is very kind of you.’

She made herself smile at the man, and he said, obviously pleased, ‘That’s better, Ma’am. This way, if you please.’

He led them down the path and round the wild, ragged front hedge. At the halfway mark, it suddenly became a neatly trimmed privet, and he led them into a front garden boasting a few daffodils and other small spring blooms. Near the house wall, sheltered from the cold wind, a blaze of red tulips stood tall and straight as an honour guard. The front window was neatly draped with lace curtains, and the front door stood open, giving a glimpse of a flowered stair carpet.

They entered through a lobby similar to the other one next door, though it lacked the stained-glass window in the inner door and the tiles were covered by a large doormat.

They carefully wiped their feet as they went in, and looked down the passageway with some curiosity.

It had the same brown paint with cream upperworks as the house they had just been in. It was, however, spotlessly clean, and the hall runner was thick cream wool with a lively Turkish pattern in dark reds and greens. Celia looked at it and hesitated to step on it.

‘My shoes must still be muddy from the garden,’ she said doubtfully to the old man.

‘Don’t worry, luv. The carpet cleans up fairly easy.’ He smiled at her and at her mother behind her, and gestured towards the colourful stair carpet. ‘Alice and me, we hooked all the carpets in the house. Pure wool, they are. They sponge clean something wonderful.’

Murmuring polite amazement at such industry, the ladies were ushered into the back room, where a good coal fire glowed. ‘Come in, come in and warm yourselves.’

He eased a rather bewildered Louise into a battered rocking chair, and told Celia to take the chair opposite, which was a low nursing chair with a padded seat and back, its velveteen worn with age.

As she sat down, she wondered how many babies Alice had fed while seated in the armless chair. She spread her skirt comfortably round her, and, a little sadly, thought how good it must feel to have a baby at the breast and be cosy with it by the fire. Then, as Mr Fairbanks hurried to get his best, flowered cups and saucers out of a corner cupboard and set them on a table in the centre of the little room, she almost blushed at her wickedness at harbouring such an idea.

Her duty was to her mother; she had been taught that in childhood, and, anyway, at aged twenty-four she was on the shelf – too old to think of marriage and babies.

Edna had been the pretty one, who had been groomed for marriage and had gone triumphantly to the altar with Paul Fellowes, a good solid match. Her father had, however, been worried when a besotted Edna had insisted on following her husband out to Brazil, though she was pregnant with their first child. Her daughter had survived being born in a hot climate, only to die of dysentery at the age of two. There had been no other children, and Celia often wondered why. Her friend, Phyllis Woodcock, had told her ruefully that babies arrived every year.

Edna was lucky that Paul was still alive. Had it not been for the contract in Brazil, he would surely have volunteered for the army at the beginning of the war, and it would have been remarkable if he had managed to survive until the conflict ended. She wondered if he had felt any regret at not being able to come home and fight – or had he thankfully made the business contract with Brazil, an allied country, an excuse not to have to sacrifice himself for king and country?

The latter was such an ignoble thought that she immediately turned her attention back to her mother.

Louise was sitting silently, her eyes half-closed, as the fire warmed her frozen feet. Her sudden spate of rage was draining away, and she felt dreadfully tired. She longed to lie down in the cosseting safety of her own bed.

After a few minutes, she roused herself sufficiently to take off her gloves and allow the heat to warm her hands. While Mr Fairbanks bustled into the kitchen to fill the kettle, Celia whispered to her, ‘When do you think Paul and Edna will dock?’

Before replying, Louise waited for Mr Fairbanks to push between them to place the kettle on the hob, and turn it over the fire. It soon began to sing, and Mr Fairbanks said cheerfully, ‘It won’t be long, Ma’am.’

Louise acknowledged his remark with a condescending nod, and then, as he vanished in search of milk and sugar, replied to Celia, ‘I really don’t know. Albert thought it would be within two weeks. He thought it very likely that they had sailed a day or two before … before …’ Her lower lip began to tremble.

Celia’s voice was very gentle, as she suggested, ‘So that it is possible that they will not receive his letter – or your letter to Edna?’

‘Yes, dear.’

‘That’s what he said to me. In any case, once they get word in Southampton, I am sure they will take the first train up here.’

‘Yes, dear.’

It was Celia’s turn to sigh. ‘I wish they were here. Paul would know what to do about everything.’ She felt like adding, ‘And he would know how to deal with Cousin Albert, so that at least we would know more exactly what our financial situation really is.’ She restrained herself, however, because she could see that her mother was crying silently to herself.

Louise’s tears had not gone unnoticed by Mr Fairbanks. It was clear that Albert had told him the reason for Louise’s coming to the cottage, because he said soothingly to her, as he rescued the puffing kettle and took it over to the table to fill the large earthenware teapot, ‘Don’t grieve, Ma’am. A good cup of tea’ll set you up.’

He stirred the pot briskly, put an ancient knitted tea cosy over it, and asked, ‘How much sugar, Ma’am?’

‘Two, please.’

‘And you, Miss Celia?’

‘The same, please.’ Really, he was being immensely kind, Celia thought, just like a grandfather would be. Both sets of her grandparents had died when she was small, and she had little recollection of them, except of veined wrinkled hands producing bonbons and popping them into her mouth, and being hugged and kissed. Her mother might not be getting much comfort from their encounter with Mr Fairbanks, but she herself was.

Before giving them their tea, Mr Fairbanks went back to his corner cupboard and produced a largish bottle.

‘Would you be liking a drop of rum in your tea, Ma’am? It might help you a bit, like …’

Louise glanced up at him. For a moment she was shocked out of her misery. ‘Oh, no, thank you. I couldn’t possibly!’ A gentlewoman drinking rum like a common sailor’s wife? Brandy, perhaps, but not rum!

Celia, however, saw the sense of his suggestion, and she said, ‘Have a tiny bit, Mother. It would give you strength. And we have yet to get to Birkenhead, to see Mr Billings – and then go home – it will take all your strength.’

Louise faltered. The remaining part of the afternoon stretched before her like a long staircase hard to climb, and she was so tired, so dreadfully tired.

Mr Fairbanks smiled at her encouragingly, ‘It won’t do you no harm, Ma’am.’

She was persuaded, and she did cheer up, though she drank her two cups of tea with her nose wrinkling up in distaste at the odour of the rum.

Eddie Fairbanks did not offer rum to Celia. As a single lady she shouldn’t be drinking anything but wine, and he didn’t have anything like that in the house.

Warmed and comforted and a little drunk, Louise relaxed enough to ask the old man if he knew what had happened to her childhood playmates, the Lytham family, who used to live in his house.

He did not know where the family was, he said. He knew only that the leasehold of both cottages had run out, and that the Lythams had not renewed theirs, but that Celia’s grandfather had come to an agreement with the earl to renew his for another hundred years. ‘Because the houses are very well built, and your granddad probably wanted to keep his in the family for holidays.’

It was obvious from Louise’s expression that she had no idea what was meant by leasehold, so Celia asked, ‘What exactly does that mean? I’ve always wondered.’

Mr Fairbanks picked up his cup of tea, and took a sip. ‘Well, you see, luv, nobody round these parts owns much land. Nearly all of it has belonged to the earl since time began. If you want to build on land round here – or farm it – you can persuade the earl to give you a long lease on it – these cottages had one for fifty years – and then you can build on it. However, at the end of the lease, you have to pay the earl to renew it; otherwise the land – and the buildings that you have built on it – revert to him, and he can rent them to somebody or pull them down.’ He put his cup down neatly in its saucer, and then added, ‘And what’s more, you’ll probably find that Mr Billings ‘as been paying a ground rent to his lordship’s agent each year on your behalf.’

Louise asked, ‘Can we sell the cottage, if we want to?’

‘Oh, yes, Ma’am, if someone is prepared to buy the lease from you. But you’d have difficulty getting a good price for it – they’re a bit isolated – it’s a fair walk to Meols railway station, and your cottage has bin proper neglected, if I may say so. And in winter the wind comes in from the sea something awful. The gentleman that came to look at it brought Mr Parry, the estate agent from Hoylake, along with him – and that’s what he said. Neither house is worth a great deal.’

Louise felt a little comforted. At least Albert had considered selling the cottage, before he had condemned her to it.

For her part, Celia swallowed hard. Pay an earl for the right to live in a house that belonged to you, but you probably could not sell? What other money problems that they knew nothing about lurked amid the present turmoil of their lives? What other financial demands could they expect? She felt faint with fear, unreasonable fear that Cousin Albert might have deserted them, leaving them penniless. He had made it clear that the price of their Liverpool home would be used as the foundation of their income, and certainly not to buy another house. Once he had sold it for them, would he be honest and hand over the money? Celia felt sick with apprehension.

Her mother must have had similar vague fears, because she said rather desperately to her daughter, ‘Perhaps we should go to see Mr Billings now, Celia.’ She rose carefully, to hand her cup to their host, and thank him quite sweetly for his hospitality. He was a mere working man – but he was male and he knew things that she did not. Like Celia, Louise began to view him as a possible pillar of support, like a good butler would have been, had she been fortunate enough to have one in her employ, instead of a giggling fool of a parlourmaid.

Chapter Four

Eddie Fairbanks insisted on walking with the ladies down the sandy lane to Meols Station, and waiting with them until the steam train chugged in. He recommended that, instead of changing to the electric train at Birkenhead Park Station, they should get a cab from that station to Mr Billings’ office. ‘Being as it’s getting late, and his office is nearer to Park than it is to Birkenhead Central.’

They took his advice, and were fortunate in catching small, rotund Mr Billings just as he was putting on his overcoat ready to go home.

As the ladies were ushered in, after being announced by his fourteen-year-old office boy, he resignedly took off his bowler hat again and hung it on the coat stand, then went to sit at his desk. As the women entered, he half rose in his chair and smiled politely at them.

The office boy sullenly pulled out chairs for the forlorn couple. Because of their late arrival, he would be late home and his mother would scold him. He returned to the outer office to sit on his high stool and depressedly contemplate the beckoning spring sunshine which lit the untidy builder’s yard outside.

Louise had retired behind her mourning veil, and Mr Billings eyed her with some trepidation: widows could be very tiresome, particularly a real lady like this Gilmore woman; they never understood what you told them. Since she showed no indication of an ability to speak, he turned his eyes upon her companion, a thin sickly-looking woman, dressed in mourning black. She must be the daughter. He smiled again.

‘Good afternoon, ladies. How can I help you?’ he inquired politely of Celia. Then, before Celia could respond, he added, ‘May I express my condolences at your sad loss. Very sad, indeed.’

There was a murmur of thanks from behind Louise’s veil, and Celia blinked back tears. They were not only tears because of the loss of her autocratic father, but tears for herself because she had little idea of how to deal with business matters – and Mr Billings represented a solid weight of them.

With what patience he could muster after a long, trying day, Mr Billings waited for one of them to speak, and, after a few moments, Celia nervously wetted her lips, and explained about the need to get the cottage at Meols into liveable shape.

While he considered this, Mr Billings brushed his moustache with one stout red finger and then twisted the waxed points at each end of it. He said slowly, ‘Oh, aye, it needs a bit of doing up if you’re going to live in it yourselves. It was rented for a good many years to a Miss Hornby after your auntie died; she was crippled and she never did aught about aught. When she died, Mr Gilmore saw no point in doing repairs on a place he didn’t use – and the rent wasn’t much. So I had the ground-floor windows boarded up – they being expensive to replace if they were broken by vandals. And that’s how it’s been for a couple of years now.’

He clasped his hands over his waistcoat and leaned back in his chair.

Celia told him about the broken bedroom window and asked if he could recommend a builder who could repair it quickly, and anything else that needed doing, like new floorboards in the hall bedroom.

He immediately wrote out on the back of one of his business cards the name and address of a Hoylake man, Ben Aspen, who, he assured Celia, was as honest as the day. ‘I’ll get my own man to put a new windowpane in for you tomorrow – I got a handyman I keep to do small repairs. Later on, you can tell Ben Aspen what else you want doing.’

She was greatly relieved and thanked him, as she carefully put the card into her handbag.

‘Don’t mention it, Miss,’ he replied, as he turned to her mother, to address the daunting veil. ‘Seeing as how you’re here, Ma’am, I’d like to speak to you about your property in Birkenhead.’

Louise sniffed back her tears and lifted her veil sufficiently to apply a black handkerchief to mop up under it. ‘Yes?’ she fluttered nervously.

She jumped as Mr Billings shouted to his young clerk, still fidgeting in the outer office, ‘George, bring the Gilmore file.’

Muttering maledictions under his breath, the youngster got down the file and brought it in and laid it in front of Mr Billings. When he was dismissed he bowed obsequiously to the ladies as he passed them.

They ignored him.

‘Now, let me see.’ Mr Billings rustled through an inordinate number of pieces of paper, while Celia watched anxiously.

‘Humph.’ He leaned back in his chair again, and addressed Louise. ‘Now, yesterday afternoon a Mr Albert Gilmore come in. Said he was your trustee – when he said it, I thought for a second that you was passed on as well as Mr Gilmore. Anyway, he says that I’m to send the cheque for your rents to him, like I always sent them to Mr Timothy Gilmore – prompt each quarter day.’

Celia drew in her breath sharply, and opened her mouth to protest, but, seeing her expression, Mr Billings continued, ‘Yes, Miss. That was my reaction, too. Them houses belong to you, Mrs Gilmore – according to my notes, they’re your dowry, and, therefore, they aren’t part of Mr Gilmore’s estate; and so I tell him – and he was really put out. But I said to him as it is one thing to send the rents to your hubby, Ma’am, for which I have had your written permission these many years – in fact, my father had it before me – but another to hand them over to a stranger I don’t know.’

He straightened up and looked at Louise, rightly proud of his personal rectitude.

Both Louise and Celia gasped at this information, and Celia felt sick, because it tended to confirm her poor opinion of Cousin Albert. It did not occur to her that Albert merely wanted to check that Mr Billings handed over the correct sum each month.

Louise was so shaken that she actually threw back her veil, to reveal a plump, blotched face, which might have still been pretty in happier circumstances. ‘But he has no right,’ she faltered.

‘Precisely, Ma’am.’

Mr Billings smiled knowingly at her. ‘But it so happened, Ma’am, that I was a trifle late making up me books this quarter and didn’t do your account till this morning. One tenant, Mrs Halloran, being late with her rent – she owed five shillings – I held back to give her a chance to get up to date before I reported to Mr Gilmore that she was in arrears. I read your sad news in the obituary column, Ma’am – and I’m proper sorry about it, Ma’am – so I held the cheque back until I heard from you. I’d have written to you in a few days, if you hadn’t come in.’

He fumbled in his waistcoat pocket and brought out a key ring. Then, selecting a key, he got up and went to a small safe at the back of the room. He took out an envelope and handed it to Louise.

‘There you are, Ma’am. A cheque for three months’ rents in total. Mrs H. paid up, and there was no repairs this quarter – it’s less me commission, of course. All rents up to and including last Saturday, payable to you today, Lady Day, as per usual, Ma’am.’

Louise looked up at him with real gratitude. She was not sure how to cash a cheque, but she did know that it represented welcome money. In her cash box at home, she had a month’s housekeeping in five-pound notes, which Timothy had given her, as he usually did on the first of each month; beyond that she had no idea what she was supposed to do about money. Behind her expressions of woe a deeper fear of destitution had haunted her as well as Celia.

Her thanks were echoed by Celia, who hastily added that they would, as soon as the cottage was habitable, be leaving their home in West Derby, Liverpool – it was already up for sale – and that she or her mother would let him know, before the next quarter day, which would be Midsummer’s Day, exactly where he should send the next cheque.

He was a kindly man, and, as he gently clasped Louise’s hand when they took their departure, he felt some pity for her. Women were so helpless without menfolk – and there were so many of them bereaved by the war. They had the brains of chickens – and it appeared to him that these two already might have a fox in the coop.

He said impulsively, ‘If I can be of help, dear ladies, don’t hesitate to call on me.’

Though Louise only nodded acceptance of this offer, Celia, whose stomach had been clenched with fear ever since her father’s clerk had come running up the front steps with the terrible news of Timothy’s sudden death, felt herself relax a little. She longed to put her head on the little man’s stout shoulder and weep out her terror at being so alone. Instead, she held out her hand a little primly to have it shaken by him and apologised for keeping him late at his office.