Полная версия

A History of Food in 100 Recipes

Records show that in addition to bread, the ancient Egyptians enjoyed a diet rich in fruit, vegetables and poultry. They used herbs, from cumin to fenugreek, and that scenes of domestic cooking were considered important for the afterlife confirms that it was as vital a part of everyday life then as it is now.

2

Kanasu broth

(Meat and vegetable stew)

circa 1700 BC

AUTHOR: Unknown, FROM: The Babylonian Collection

Recipe 23, tablet A, 21 kinds of meat broth and four kinds of vegetable broth. Kanasu Broth. Leg of mutton is used. Prepare water add fat. Samidu; coriander; cumin; and kanasu. Assemble all the ingredients in the cooking vessel, and sprinkle with crushed garlic. Then blend into the pot suhutinnu and mint.

Does the average Iraqi wandering the banks of the Tigris, munching on a minced meat kubbah, realise that he or she is treading a patch of land that 4,000 years ago saw the birth of haute cuisine?

While the Middle Kingdom of ancient Egypt developed some of the rudiments of cooking, Mesopotamia, which occupied the patch between the Tigris and Euphrates rivers, became a gastronomically advanced civilisation. The land was fertile, more fertile than today. Indeed, the people had an extraordinarily diverse diet that featured many kinds of vegetable, including leeks, shallots, garlic, rocket, chickpeas, lentils, lettuce, peas, figs, pomegranates and much more. They ate a huge diversity of cheese, up to 300 different kinds of bread and an amazing variety of soup. A Mesopotamian’s supper of bread, soup and cheese might be rather more sophisticated than our own.

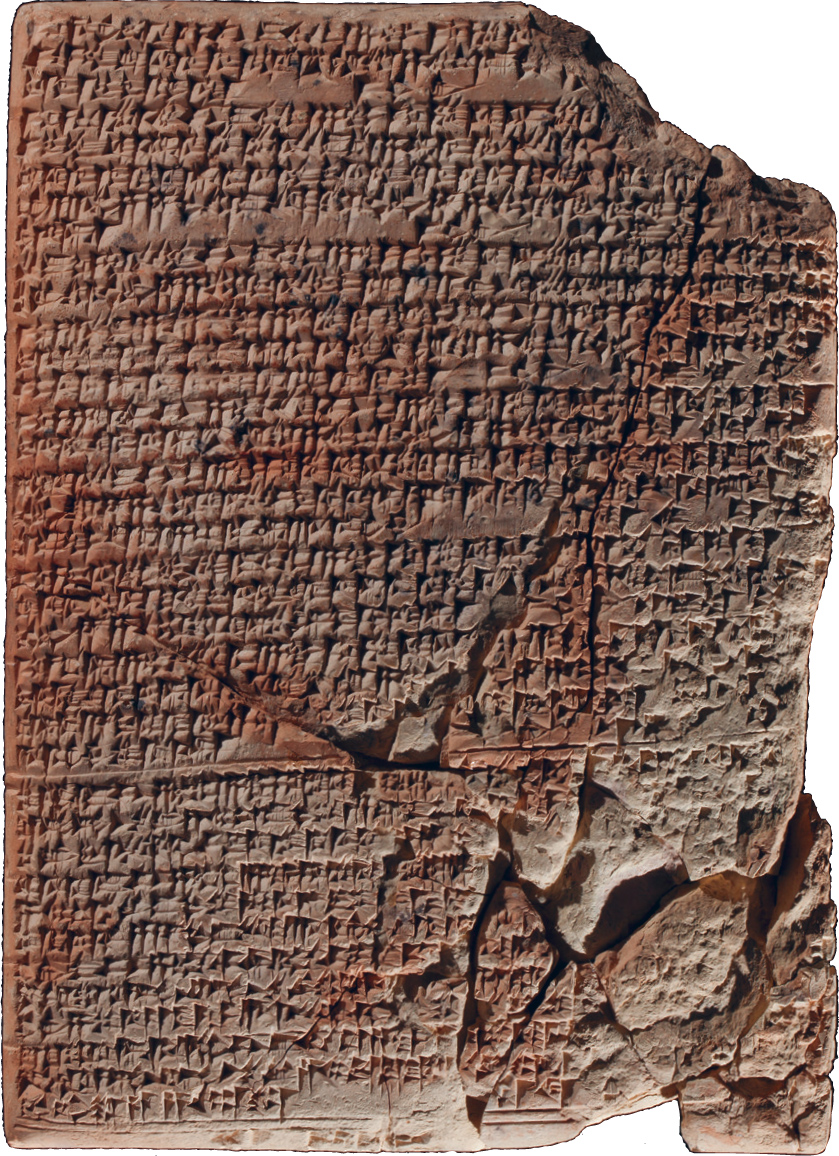

Yale Babylonian Collection

Recipe for Kanasu broth carved on a clay tablet.

We know all this from detailed records. But while today you might sketch out a recipe on a notepad, publish it in a book, put it online or on an iPhone app, in those days it was a rather more laborious process. Firstly, assuming you were a member of the rarefied and literate professional classes, you made a clay tablet, then, presumably while it was still wet, with a blunt reed stylus you slowly carved out your recipe in Akkadian cuneiform, an ancient pictorial precursor of alphabetic writing.

Many such stone tablets have lasted and survived more in less intact. At the New England University of Yale, a large number of tablets are stored as part of its Babylonian Collection, among some 40,000 artefacts acquired by the university in 1933. In an effort to preserve the tablets further, the curators had them baked and then had them copied. For many years it was assumed that the inscriptions were obscure pharmaceutical formulas but then French Assyriologist Jean Bottéro took a closer look, reporting his findings in 2004.

Focusing initially on three cracked, caramel-coloured tablets, he managed to decipher the code and on reading them discovered that they weren’t complicated equations, just recipes. The tablets revealed a rich variety of cuisine, moreover, a sophisticated mix of skill and artistry and a wonderful breadth of ingredients. Among the tablets, on a piece of clay measuring just 12 by 16 centimetres, is the recipe for kanasu broth.

Kanasu, ancient wheat – not dissimilar to durum – was mixed into a lamb stew as a thickener. Think of it as lamb casserole cooked with pearl barley. The recipe itself is brief, partly due to the time it would have taken to scratch it onto the clay and partly, as Bottéro believes, the recording of the dish constituted a kind of ritual. This wasn’t a recipe for the beginner, either: with no quantities or cooking times, it assumes a fair degree of culinary know-how.

The lamb stew is just one of twenty-one meat- and vegetable-based dishes, but it sounds a little tastier than some of the other recipes, such as one for braised turnips that begins: ‘Meat is not needed. Boil water. Throw fat in.’. Because many of the ingredients need some deciphering – samidu, for instance, was either semolina or fine white flour used for thickening, while suhutinnu was probably a root vegetable like a carrot or a parsnip – they can be hard to replicate in the modern kitchen. Indeed, having spent years deciphering the recipes, Bottéro – himself an accomplished cook – declared: ‘I would not wish such meals on any save my worst enemies.’ He may have been thinking of grasshoppers in a fermented sauce, which turns up in one of the tablets. By constrast, an editorial in the New Haven Register gave the thumbs up to Bottéro’s decoded recipe for kanasu broth, stating: ‘You can almost smell the 4,000-year-old leg of lamb bubbling in a sauce thick with mysterious Mesopotamian herbs.’.

While the dishes may not all be to the modern taste, the ingredients listed in the tablets are impressively varied, as are the various cooking techniques, suggesting that – given the number of tools required – these were dishes cooked in temples or palaces, rather than in the average home, in a mud hut, or cave, where equipment would have been rudimentary, to say the least. Recipes variously call for slicing, squeezing, pounding, steeping, shredding, marinating and straining. So even way back in the days when countries had eleven letters to their name, when people were inventing the wheel, reading the livers of chickens and believing that when you died you went underground and ate dirt, cooks were doing pretty much what most still do today.

3

Tiger nut sweets

circa 1400 BC

AUTHOR: Unknown, FROM: The Bible, Genesis 43: 11

And their father Israel said unto them, If it must be so now, do this; take of the best fruits in the land in your vessels, and carry down the man a present, a little balm, and a little honey, spices and myrrh, nuts and almonds.

Don’t think that food in prehistorical times was entirely savoury – all roasted lamb, flatbreads and chickpeas. After all they were human, just like you and me. And while I might crave a HobNob come four o’clock, so the ancients would have needed to sate their cravings for sweet things.

If we are to believe the story of Joseph’s rise to prominence in Egypt – and a large entertainment industry depends on it, or his colourful coat, to be precise – then archaeological evidence suggests he may have lived around 1700 bc.

According to the biblical account, after Joseph’s jealous brothers had forced him into exile – selling him as a slave to people travelling into Egypt – he rose in prominence partly due to his gift for interpreting dreams in which he advised the Pharoah to store up food during the good years, in anticipation of lean years to come. Sure enough those lean years came and people flocked from neighbouring countries to buy grain, including Joseph’s estranged brothers, looking for food to take back to famine-ravaged Canaan.

Joseph, rewarded with king-like status for his dream-interpreting and so grand now that they don’t recognise him as their long-lost brother, permits them to take food back to their family, saying that they can have more food but only if they return with their younger brother Benjamin. This they tell their father back home, who is suspicious at first but then relents. He then sends off his sons with advice and a few things in their pockets that unwittingly ensures him a place in A History of Food in 100 Recipes. For take a closer look at what he stuffs in those pockets: honey, spices, nuts and almonds. All the ingredients, in short, for tiger nuts.

No doubt he also popped a recipe for them in Benjamin’s top pocket. It was an early example of the tradition of taking a sweet gift to someone as a sign of appreciation or affection. Fragments of such a recipe exist on scraps of parchment from the same era and they are called tiger nuts because they resemble the tuber root of the same name. They are thought to be the earliest sweets and, with their sticky mix of honey, dates, sesame seeds and almonds – blended together and rolled into balls – are pretty nutritious too. Try them after dinner with a dark, black cup of intense coffee. And make sure to don a dressing gown or cloak decorated with a patchwork of colours, for added authenticity.

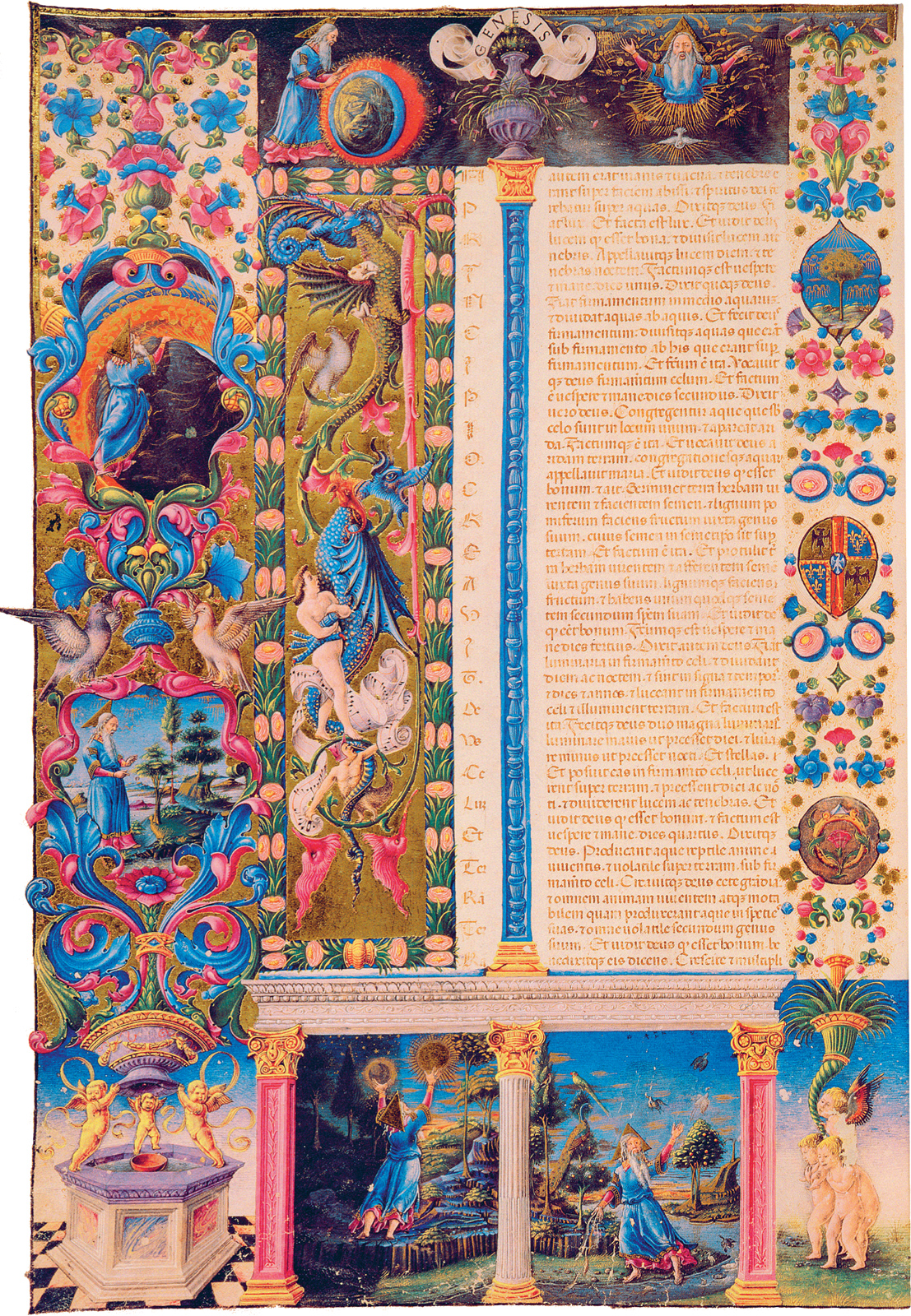

Bridgeman Art Library: Biblioteca Estense Universitaria, Modena, Italy

A piece of fine parchment paper showing Genesis, the creation of the universe, from the magnificent Italian Renaissance Bible of Borso d’Este Vol 1.

4

Fish baked in fig leaves

350 BC

AUTHOR: Archestratus, FROM: Hedypatheia (Life of Luxury)

You could not possibly spoil it even if you wanted to … Wrap it [the fish] in fig leaves with a little marjoram. No cheese, no nonsense! Just place it gently in fig leaves and tie them up with a string, then put it under hot ashes.

Archestratus’s mission in life was to visit as many lands as he could reach in search of good things to eat. A Sicilian, he ventured all over Greece, southern Italy, Asia Minor and areas around the Black Sea. He tasted his way to paradise and then recorded it in classical Greek hexameters. Not the way one might record recipes these days, but maybe he felt it added a lyrical nuance to his findings, as well as a playful parody of epic poetry.

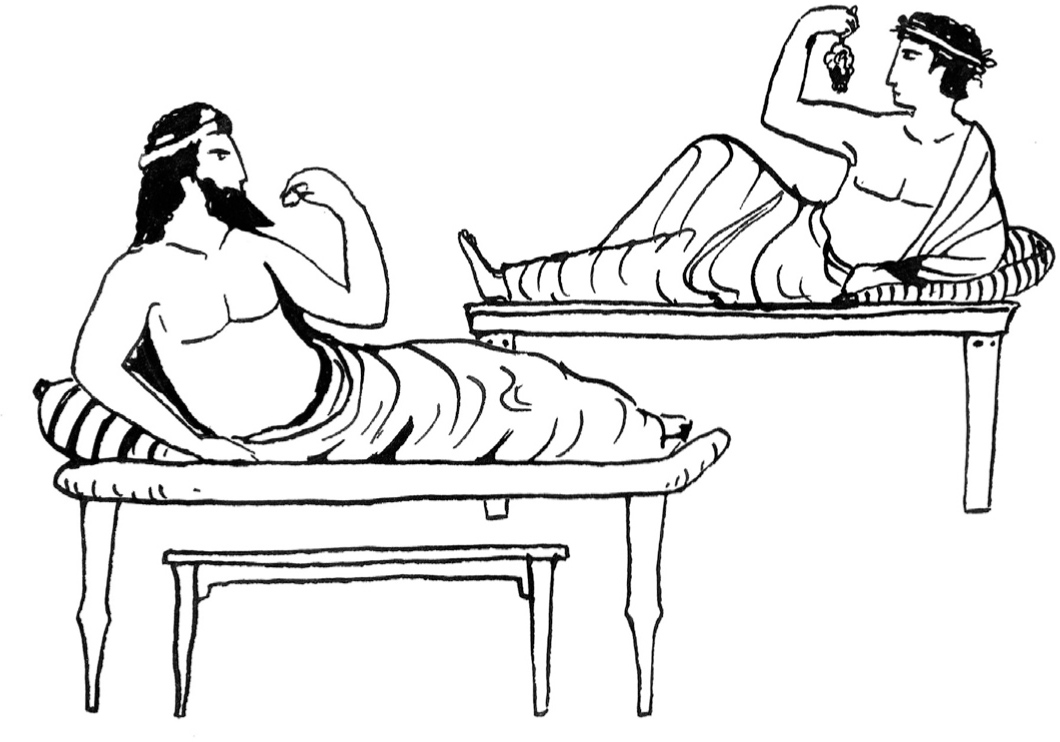

The entire project was recorded in the form of a poem appropriately entitled Hedypatheia or ‘Life of Luxury’. And while only fragments of it remain, there are enough of them for us to get a good idea of the food he ate, what he thought of it and, vitally, how it was cooked. Archestratus’s writings on ingredients, dishes and his views on flavour combinations paint a picture of the well-to-do of ancient Greece in around 350 bc. Their tastes were cosmopolitan and they appear to fit the stereotypical image of them taught at school – lying languidly on couches, eating in a reclining position, grapes dangling from their fingers.

The poem shows Archestratus to be a man of strong likes and dislikes. He was not a great eater of meat, for instance, its link with religious sacrifice making it less appealing as a dish for feasting, but he loved sea and river food. Of the sixty-two fragments that remain of his poem, forty-eight concern fish. He divided these into two categories: tough fish that needed marinating and the finer type that could be cooked straight away. And his guiding principle in cooking it was simplicity. He believed that the better quality of the raw product, the fewer additional ingredients the cook needed to add. Cooking should be simple – preferably grilling with the lightest of seasoning and oil, such as in this recipe for cooking a variety of shark: ‘In the city of Torone you must buy belly steaks of the karkharias sprinkling them with cumin and not much salt. You will add nothing else, dear fellow, unless maybe green olive oil.’ The recipe for baked fish, at the top of this chapter, is prepared with a similar lack of fuss.

‘All other methods are mere sidelines to my mind,’ he wrote. ‘Thick sauces poured over, cheese melted over, too much oil over – as if they were preparing a tasty dish of dogfish.’ Perhaps this was a rebellion against the meals he had endured as a child, which could be very rich as well as over-abundant. As Plato wrote disparagingly: ‘[Sicily is] obsessed with food, a gluttonous place where men eat two banquets a day and never sleep alone at night.’

As well as his disdain for sauces, Archestratus was insistent on what he considered were worthy ingredients. ‘Eat what I recommend,’ he said. ‘All other delicacies are a sign of abject poverty – I mean boiled chickpeas, beans, apples and dried figs.’ And he was obsessed with where food came from and where the best ingredients were to be found. ‘Let it come from Byzantium if you want the best,’ he wrote, like the voiceover of an early product endorsement.

Of the few meats he liked – hare, deer, ‘sow’s womb’ and all sorts of birds, from geese to starlings and blackbirds (animals not used for sacrifice, that is) – he preferred the following method of serving: ‘[Bring] the roast meat in and serve to everyone while they are drinking, hot, simply sprinkled with salt, taking it from the spit while a little rare. Do not worry if you see ichor [blood – used normally with reference to the Greek gods] seeping from the meat, but eat greedily.’ As with cooking fish, the principles are of a dish simply prepared and served.

Highly opinionated Archestratus may have been, but he was also extremely knowledgeable. Indeed, he demonstrated a sophisticated appreciation of the various parts of a fish, writing of the subtle differences in texture between the flesh of the fin, belly, head or tail. Subsequent writers relied on his expertise. Athenaeus of Naucratis, author of the Learned Banquet in around AD 200 and a man without whom we would have little knowledge of the cultural pursuits of the ancient world, was much influenced by his predecessor. He wrote of Archestratus: ‘He diligently travelled all lands and sea in his desire … of tasting carefully the delights of the belly.’

While his musings on food are appealingly vivacious, Archestratus’s recipe writing is deliciously free and passion-fuelled, such as when championing the finest-quality ingredients: ‘If you can’t get hold of that [sugar], demand some Attic [Greek] honey, as that will set your cake off really well. This is the life of a freeman! Otherwise one might as well … be buried measureless fathoms underground.’ Probably the world’s earliest cookbook, Life of Luxury has all the energy and colour of a modern bestseller.

5

To salt ham

160 BC

AUTHOR: Cato the Elder, FROM: De agri cultura (On Farming)

Salting of ham and ofellae [small chunks of pork] according to the Puteoli [a Roman colony in southern Italy] method. Hams should be salted as follows: in a vat, or in a big pot. After buying hams [legs of pork] cut off the hooves. Use half a modius [a dry measure equivalent to about 9 litres (2 gallons)] of ground Roman salt per each ham. Put some salt on the bottom of the vat or pot, and place the ham on it skin downwards and cover it with salt. Then, place the next ham on it skin downwards and cover it with salt in the same way. Take care that the meat does not touch … After all the hams are placed in this way, cover them with salt so that the meat cannot be seen; make the surface of the salt smooth. After the hams stay for five days in the salt, remove them all, each with its own salt. Those that were on top should be placed on the bottom and covered with salt as previously. After twelve days altogether take the hams out; remove the salt, hang them in a draught and cure them for two days. On the third day, take the hams down and clean them with a sponge, smear them with olive oil mixed with vinegar and hang them in the building where you keep the meat. No pest will attack them.

Roman politician Marcius Porcius Cato was brought up on a farm south-east of Rome near a city called Tusculum. He enlisted as a solder at seventeen and later rose to high office as a statesman, known as a skilful orator who made use of his public-speaking prowess by chastising those in the Senate whom he felt were too liberal. This accorded with his latter role as censor, an official position that included supervising public morality and which he took to with enthusiasm. With his clamp-down on immoral officials and support of a law against luxury, he was identified with the job – known to posterity as Cato the Censor. He was censorious about those he thought were extravagant – he wouldn’t have approved of the creamy sauces that came out of Apicius’s kitchen 150 years later – while the first-century historian Plutarch praised him not for any triumphs as military leader but that ‘by his discipline and temperance, [he] kept the Roman state from sinking into vice’.

Perhaps it was his childhood on the farm that had instilled in the young Cato a Spartan frugality. His father apparently died while Cato was quite young and he inherited considerable responsibilities, learning the business of farming in his early teens. As an older man, he ate with his servants, was a strict parent, a harsh husband, an inflexible official and, by all accounts, a downright bore.

He was also a prolific author, although only fragments tend to remain of his writings. He wrote a history of Italy in Latin, published a collection of his speeches – including the deadly retrospective On His Consulship (he’d been a consul before discovering his métier as censor) – and a tome entitled On Soldiery. Not even fragments of the latter remain but one can imagine the sort of thing it might have included: dawn rises, cold showers, spotless uniforms and suicidal charging at the enemy.

But one volume that has survived completely intact is his De agri cultura, or ‘On Farming’. A manual on good agricultural practice, it advises, for example, how many slaves to hire for the olive harvest and how – in one particularly charming note – a slave’s ration might be reduced should he be so audacious as to fall ill. It also gives details on how to preserve food, including the earliest recorded description of how to salt pork – the recipe that heads this chapter. In addition Cato offers recipes for pickling and smoking, and his writings show that he had considerable expertise, employing methods that would be just as workable today.

Knowing how to preserve meat, fish or indeed fruit was vital in the centuries preceding the advent of the supermarket and the fridge. Indeed Polish professor Maria Dembinska, writing in the late twentieth century, has described it as ‘the greatest worry of primitive man’. In the days when finding food for everyday consumption was a trial, if not life-endangering, its preservation was all the more important. That ever-present fear of hunger challenged man’s ingenuity to find methods to both preserve food and then store it effectively.

How much less meat we might waste today if we had to hunt it ourselves – if we had speared it while it was charging at us. Preserving food was necessary not just so that it would last beyond the weekend but because food might be sourced at quite a distance from where it would be consumed. So people buried food in situ. Excavations on the Irish and Norwegian coasts have uncovered bones, for example, from fish buried between 5000 and 2000 bc. That they were excavated shows a skill in burying fish, if not in retrieving it. Without a map to mark the spot, that fish remained buried for rather longer than was perhaps intended.

Herodotus, meanwhile, wrote 2400 years ago of the Babylonians and Egyptians drying fish in the wind and the sun. And meat was often hung in the roofs of houses. Perhaps that is how it came to be smoked – by mistake over a home fire, but resulting in another method of preserving food as well as enhancing the flavour. The Vikings may have developed this concept, although no records exist to confirm this. Once it was discovered that salt was a proficient preserver, that idea quickly spread too. By 1800 BC there were salt mines all over the place. Although many still preferred to bury their fish, particularly in the lands of the north.

A Swedish census from 1348 records the existence of a man called Olafuer Gravlax. He lived in Jamtland in central Sweden and as his surname means ‘buried fish’ we can assume that that’s what he did. Whoever first produced gravlax – cured salmon – in Scandinavia probably did it by mistake, his aim simply being to store fish for the winter season when freezing temperatures and ice-covered rivers and lakes would have made fishing almost impossible. Burying it also would have kept it away from thieves – from ‘those on two, as well as those on four legs’, as the Norwegian author Astri Riddervold puts it.

So he buried his fish. Then when he dug it up months later, it would have stunk, horribly, having lain underground and then fermented. But, ignoring the smell, whoever dug it up then bravely tasted it and found it not just to be edible but to have a remarkable flavour, albeit very different from that of the fresh fish he had buried all those months before. It was a miracle. The following season, maybe he added salt to one fish, a little sugar to another and sugar and salt to another. Perhaps he then experimented to see what happened if he stored it for less time – a few months, weeks, then days.

Who knows quite how it happened and when it became an established practice. But people liked the tart taste and it became a culinary tradition, not to mention a commercial enterprise. Indeed, while Olafuer Gravlax buried fish he may not have run the entire business. This we can surmise from another record – this time in the 1509 annals of Stockholm – which lists one Martin Surlax, whose surname translates as ‘sour fish’. So as sour fish is the result of burying fish, perhaps Mr Gravlax buried it while Mr Surlax dug it up.

Gravlax brings echoes of the 1980s, when it was all the rage in Britain, served at dinner parties with dill sauce. These days you don’t of course need to bury it to make it as a trip to the supermarket makes its procurement rather easier. And with the addition of salt, sugar, dill and some spices (peppercorns and coriander seeds), you can even do your own burying – in the fridge for just two days. Back in the fourteenth century it wouldn’t have been quite so straightforward, but those early fish buriers were clearly on to something. They may have been using their instincts when they added salt and sugar, but they were unknowingly engaging in a very complicated scientific process. The salt drew out the water but also refreshed the proteins and preserved the fish.

Be they medieval fish buriers who cured salmon for a living or a Roman disciplinarian who salted pork in his spare time, these early innovators used their ingenuity to keep hunger at bay. Meanwhile, the techniques that once staved off real hunger in former times now sate the greed of the modern snacker today. For where would we be without all those salty, sugary goodies to make us obese and thirsty?

6

Roast goat

30 BC

AUTHOR: Virgil, FROM: Georgics II: 545

Therefore to Bacchus duly will we sing,

Meet honour with ancestral hymns, and cakes

And dishes bear him; and the doomed goat

Led by the horn shall at the altar stand,

Whose entrails rich on hazel-spits we’ll roast.

You may not consider Virgil to be a recipe writer, yet here is what amounts to a recipe for goat, roasted on an early version of a spit. And I’m not the only one who has cited this extract as a recipe. It was quoted back in the 1800s, to illustrate the simplicity of roasting as a cooking method. In a section entitled ‘The Ladies Department’ in an 1825 edition of the US publication the American Farmer, the poem is referred to with the comment that ‘Roasting is the most simple and direct application of heat in the preparation of food.’ While four years earlier, in 1821, Frederick Accum in his Culinary Chemistry also cites Virgil, going on to say: ‘Roasting on a spit appears to be the most ancient process of rendering animal food eatable by means of the action of heat.’

Before metal spits were devised, meat would be skewered onto branches pulled from trees – often hazel wood, as in Virgil’s poem. The sap in the wood, when heated, would make the branch turn (so long as the animal being cooked was light enough, such as a small bird like a lark; it wouldn’t happen if you skewered a pig on it) and people who witnessed it thought it supernatural. Hazel was also used as a divining rod.

But quite how roasting came about can only be guessed at. For thousands of years the human race ate its food raw, and then between the discovery of how to make fire and the appearance of the Neanderthals, man began to cook his food. So at some point, while using fire for warmth or to ward off wild animals, a discovery was made. Did the spark from a fire catch light and burn down the lair of some wild pigs? Did man smell the roasting fat and try out the first pork scratchings? Or did a grazing mammoth fall into a fire pit, the smell of its cooked flesh wafting on the wind in an appetising new aroma?