Полная версия

The Shadow Of The Bell Tower

It’ll be dark soon down there, thought Lucia. I’ll need a light source.

She went into the barn and gave Morocco a little talk, and claimed the carrot the girl used to bring him as a gift. Lucia pulled it out of her pockets and the animal was quick to take it gently with his lips from her hands. She caressed the horse on the back of his nose, looking for a lantern. She saw it, unhooked it from the nail to which it was attached, checked that it was loaded with oil, then concentrated her gaze on the wick, which in a few moments caught fire. Lucia regulated the flame to the minimum, came out of the stable and ventured down the uneven stairs towards the bowels of the earth. Although Earth was one of the elements she had control over, she was a little afraid of it at the time. It almost seemed as if that ladder should never end, because it was so long. But maybe it was just Lucia’s impression. She finally left the last step with her foot. The humidity was strong down there, the girl was freezing the sweat on her, and her breath condensed into little clouds of steam. She raised the lantern flame. There were several corridors, bordered by ancient stone walls and rough bricks. One, very long, was lost in the darkness ahead. Grandmother had told her that there was a long passageway that could be used during sieges, to cross enemy lines and provide supplies for the besieged people and weapons for the city’s defenders. This passage even came out at the country residence of the Baldeschi family, at the beginning of the road to Monsano, a small town located a few leagues away from Jesi, and always a historical ally of our city. On its right, a tunnel would certainly have quickly reached the underground of the cathedral, perhaps even the crypt that housed the relics of St. Septimius. The tunnel on its left could have led to the base of the church of St. Florian, like the ancient Roman cistern. Who knows if the latter was still full of water, Lucia wondered. She decided to go to her right, towards the basement of the Cathedral and, in short, she found herself in a small square chapel. Four white marble statues, without the head, like columns, supported the cross vault of the chapel. Probably, they were statues that had once adorned the Roman baths. Without the heads, which lay piled up in a hidden dark corner, they were used by those who had once designed the cathedral as columns. In the centre of the chapel, under the vault supported by Gothic arches, a small stone altar framed a shrine containing the relics of the first Bishop of Jesi, Septimius. The Saint, like many Christians of the time, had been martyred at the behest of the Roman authorities. The Roman dean who governed the city of Jesi had ordered its beheading, after Septimius had converted to Christianity a large part of the population, including the governor’s daughter. Septimius had been considered a dangerous enemy of the Roman Empire and executed. The bones had been stolen by the first Christians to save them from the desecration of the pagans, and hidden so well that for centuries and centuries no one knew where they were. The Saint was beheaded in 304 and his mortal remains were found only after 1,165 years in Germany. Therefore they had been brought back to that place of worship only about fifty years earlier.

How strange humanity! Lucia said to herself. The same treatment that the Romans gave to the first Christians, who were persecuted, now the Catholic Church seems to give it to those people who do not think like her: who deviate from the official doctrine are accused of heresy and may end up killed in the public square. Witches, heretics, Jews... are tried and burned at the stake, just because they have the courage to express their ideas and knowledge. Well, now the Church takes it out on heretics, tomorrow, in the future, some other faction will take over and perhaps Christians will be persecuted again. Why should there not be justice in this world? What is this God who allows so much evil to exist in the world, but especially in the heart of man?

As she followed the course of her thoughts, a blade of light generated by a setting sun managed to filter through a small mullioned window at the top, at the apse of the cathedral above, illuminating the area where the heads of the Roman statues were piled up. Lucia’s attention was focused on some details that she had not been able to notice before, there near those heads carved in stone so many centuries earlier. A kind of pentacle had been drawn on the beaten earth floor, different from the one she used to see drawn on the cover of the family diary given to her by her grandmother some time before. The design seemed asymmetrical, representing a seven-pointed star carved out by drawing a continuous line within a circle. Each point of the star intersected a point on the circumference, at each of which there were Hebrew inscriptions, whose meaning Lucia did not know. At each of the seven points, the trace of wax cast, left by a candle that had been lit there, was visible. In the centre of the figure were two rag dolls, made of straw around which miniature clothes had been wrapped. They represented an old woman and a girl: the old woman’s clothes were burnt, while the young woman had a brooch fixed to her chest. Lucia gasped, her heart started beating wildly, and in a flash she understood everything. Some black magic rituals had been performed there, and the dolls represented her and her grandmother. It was clear that someone wanted to see them suffer, if not even die. Who? Who could it have been? Only one person could have gone down there. The church above was now closed, forbidden to the faithful for more than a year, so the crypt could not be reached from the cathedral. The passage you had walked through was closed by a constantly barred door, and only her uncle, the Cardinal, the Chief Inquisitor Artemio Baldeschi, had the key. Certainly, it had been too long since there had been no executions in Jesi, the last fire had been lit six years earlier, the one in which Lodomilla had lost her life. Now the Cardinal had to quench his thirst, his desire for victims, his desire to witness suffering and death directly before his eyes, under his gaze. Yes, because unlike the majority of the inquisitors who, once the sentence had been pronounced, handed the victim over to the secular arm of the Law, avoiding witnessing the torment of those they had condemned, Artemio used to attend the execution, in the front row, sometimes holding the torch and setting fire to the stack. He seemed to have a sadistic taste in seeing his victim writhing in the flames, he kept staring at her with his eyes until the end, and for a precise reason: to capture the soul of the condemned man the very moment he left his mortal body.

Emaciated by these reflections, frightened by what she had seen, Lucia grabbed the lantern and rushed up the stairs, her mind occupied by a single fear. Would she find the door open again? What if Uncle had remembered not to lock it and returned to close it? Or what if he did it on purpose, to induce her to go down there and bury her alive? No, it wouldn’t have been enough for Artemio, he had to see his victim’s suffering in the face, it wouldn’t have been like him to let her die there. He just wanted to scare her, and he succeeded. The little wooden door was open, Lucia went out into the hall, rested the lantern where he had taken it, she didn’t even look at Morocco and rushed into the open air, into the Square, still with the heart in her throat.

It was almost the sunset of a warm day at the end of May and the reddish light of the sun gave spectacular colours to the beautiful square where, more than three centuries earlier, Emperor Frederick II of Swabia was born. She said to herself that she should research the meaning of the symbols found in the crypt in the family diary, in the precious manuscript that her grandmother had given her. But now she had to calm down, and decided to take a walk around the city. She crossed the square, reaching the opposite side, turned left and went down to the Longobards’ Coast, to reach the lower part of the town, where merchants and craftsmen lived. The palaces were less sumptuous than those in the upper part of the city, but they were nevertheless enriched with decorative elements, with finished portals and frames around the windows. The facades were almost all embellished with plaster, painted in pastel colours, such as light blue, yellow, ochre, soft orange; it was difficult to leave bricks face to face, as it was for the stately palaces up in the centre. As a reminder that those residences had been built thanks to the money earned by those who lived there, often on the lintels of the portals or windows of the first floor there were inscriptions such as “De sua pecunia” or “Suum lucro condita - Ingenio non sorte”. At the end of the Longobards’ Coast, turning right, you could quickly reach the church dedicated to the apostle Peter, built by the Longobard community living in Jesi in the second half of the tenth third century. “Principles Apostolorum – MCCLXXXXIIII”, could be read above the portal; those who had engraved the date no longer had much memory of how the numbers were written in Latin, or perhaps they had never known it being an architect of Byzantine origin, already used to dealing with Arabic numerals, much easier to memorize. Opposite the church, the Franciolini’s Palace, just completed, was the residence of the People’s Capitan, Guglielmo dei Franciolini. He too had made his fortune as a merchant since, after the discovery of the New World, new commercial channels were opened and many new merchandise had also arrived in Jesi. Those who had been able to take advantage, had succeeded in a short time to accumulate considerable wealth. Lucia dwelt on the rich portal of the palace, limited by two columns and some square sandstone tiles, decorated with depictions of gods and symbols of Roman times. In all probability, while excavating the foundations of the house, decorative elements of a house of some Roman patrician had been found, and these had been reused to embellish the portal. Lucia recognized the God Pan, Bacchus, the Goddess Diana, and then some three-pointed lilies, and... a six-pointed star formed by two crossed triangles - strange, wasn’t it the symbol of the Jews? - and again a five-pointed star, a pentacle, and... a seven-pointed design inscribed in a circle, similar in every way to what he had seen just before in the crypt. These last drawings could not date back to Roman times, and in fact, looking carefully at the tiles on which they were made, one could see that these were of different features, more recent than the others, perhaps made for the purpose of decorating the portal. But what was the meaning of all this? In that little square the sacred coexisted with the profane: on the one hand the church dedicated to the principal of the apostles, to Peter, the first Pope in the history of Christianity, on the other hand pagan figures and symbols that could accuse the landlord of being a heretic. And yet the uncle Cardinal was on good terms with Franciolini, he had even proposed his son to her as her future husband! The more she looked at those symbols, the more Lucia thought that the place had something magical. Perhaps that palace had been built over the ruins of a pagan temple, and had kept its peculiarities. She tried to focus, to open her third eye to the vision, she invoked her spirit, to make it hover high and peer at elements that she would not otherwise have seen. Already in his cup-shaped hands, the semi-fluid ball of colours was materializing, when the door of the palace suddenly opened wide, showing in the half-light a young man wearing light battle armour, riding a powerful steed in turn harnessed on his head to protect him from any blows that might be inflicted by swords and spears.

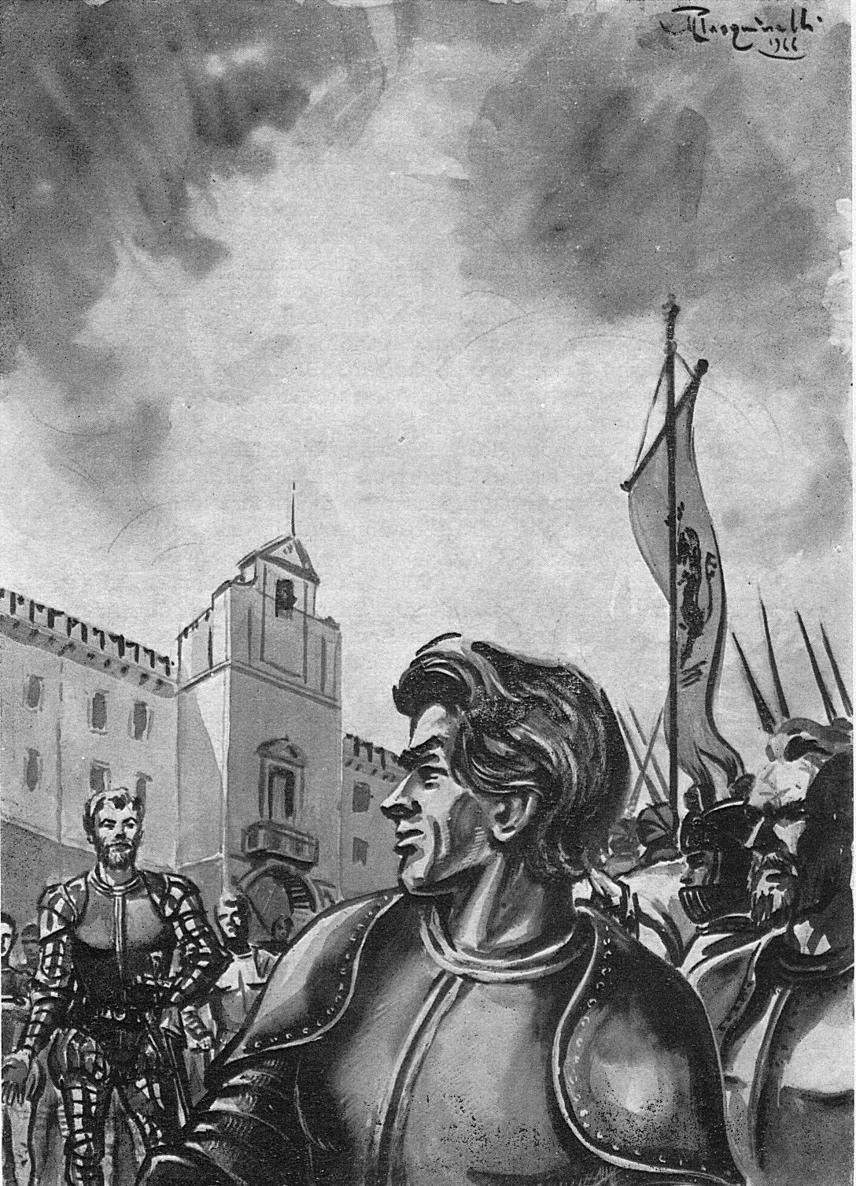

The knight held with his right hand the banner of the Republic of Jesi, representing the rampant lion adorned with the royal crown. As soon as the door was completely open, he spurred the horse outside, almost overwhelming Lucia who was there in front. The girl, frightened, became distracted, and the sphere immediately disappeared. The horse, in front of the unexpected obstacle, soaring, kicking in the air with its front paws. Lucia felt a hoof at a very short distance from her face, but she did not panic and stuck her gaze into the sea-blue eyes of the rider, whose helmet visor was raised. For a moment he lost herself in those eyes, the horse calmed down and the knight looked back at the damsel, staring in turn at the girl’s hazel eyes. There was a moment of calm, of total silence, the crossing of the two glances seemed to have stopped time.

Who was that handsome knight, ready for a hypothetical battle to defend his city? Was it Andrea? If it had been, she should have been grateful to her evil uncle! But maybe Franciolini had other children. She didn’t have time to open her mouth, because after a few moments, the bells of St. Peter’s church began to ring, and gradually they were joined by those of St. Bernard’s church, then those of St. Benedict, and finally those of St. Florian. Throwing a last glance at Lucia, the knight spurred the horse again, reaching the nearby Piazza del Palio4 , the huge open space inside the walls, dominated by the Torre di Mezzogiorno5 . In short, other knights in arms squeezed around the one holding the banner, then came people on foot, armed with crossbows, daggers and any other weapon that could be used against the enemy.

«The Anconetans are attacking us!» cried the noble Franciolini. «Our lookouts sighted them from the Torrione del Montirozzo6 . Today, May 30, 1517, we prepare to defend the walls of our city.»

All the city gates were closed, the majority of the men on foot set out on the guard’s walkways, while the knights gathered in the square inside Porta Valle7 , ready to sortie against the enemy. But for that night, the Ancona army, led by Duke Berengario di Montacuto, did not approach to Jesi, but remained camped further downstream, a few leagues from the town of Monsano, half-hidden in the riparian bush near the Esino River.

For a few days the alert remained. At dusk, the Scolte8 reached the terraces, to strengthen the guard usually given to some lookouts, and from the walls resounded the call of a song that the population had not heard for several years:

«The trumpet sounded, and the day was over,

already by curfew the song went up!

Up, up, to the armed guard towers, there,

Be careful, quietly watch out!»

The People’s Captain had imposed a curfew on the citizens. At 9:00 p.m., those who did not go up to the stands of the walls had to strictly retire into their homes. But the guard was bound to drop early. For the evening of June 3, a party was planned at Palazzo Baldeschi, where the engagement of the Cardinal’s niece, Lucia, with the cadet of the Franciolini’s house would be announced. In those days, every time Lucia crossed her uncle’s eyes, even if she was unable to read his thoughts, she saw only one word drawn on her face: “betrayal”. But she could not understand what interpretation to give to that word, at the same time so simple and so complex.

Chapter 2

Guglielmo dei Franciolini, People’s Capitan of Jesi, was a wise administrator, and he knew well that it was not the case to authorize a sumptuous party just in the days when the enemy was at the gates of the city. But he could not go against the Cardinal, reviving once again the disagreements between civil and ecclesial authorities. Just a few years earlier, the Government Palace had been completed and inaugurated with the blessing of Pope Alexander VI himself, who had granted the citizens of Jesi to continue to adorn the lion with the royal crown, provided that ecclesiastical authority was observed in the city and the countryside. So much so that on the facade of the palace one could read, above the symbol of the city, the inscription “Res Publica Aesina - Libertas ecclesiastica – MD”. And so the infamous Pope Rodrigo Borgia had granted a certain freedom to the Republic of Jesi, provided that it was nevertheless subjected to the power of the Church. With this agreement, the Jesi’s people were also spared the horrors perpetrated in the rest of the Marches by the Pope’s son, Cesare Borgia, who had proposed to become absolute lord of Romagna, Umbria and the Marches with ferocity and betrayal. It was past history, almost twenty years earlier, but in any case Guglielmo had to respect the pacts. Moreover, it was the engagement of his son Andrea with the Cardinal’s niece that further sealed the agreement between the Guelphs9 and Ghibellines of his city. After all, the enemy had been camped a few days ago on the banks of the river, much further downriver, and did not mention moving. On those curfew nights, the lookouts and the Scolte had not noticed any movement; the camp’s bivouac fires were clearly visible, almost kept burning all night long by the people of Ancona. The fear, not unfounded, of Guglielmo and his son Andrea, was that all this was a trick. Perhaps the enemies were waiting for reinforcements to attack, or perhaps they drew the attention of the Jesi’s inhabitants on that small camp, while the bulk of the army would appear elsewhere. The afternoon of Thursday, June 3 had been particularly hot. While Guglielmo was preparing for the ceremony, helped by some servants to wear elegant and colourful brocade dresses, which helped to increase his sweat production, he finished giving orders to the commanders of his guards.

«From vespers onward all the gates of the city must be closed. Also set up chains in the main streets, so that if the enemy breaks in, his progress will be hindered.»

The lieutenant interrupted him.

«The cardinal has made opposing arrangements, my lord. He wants all the gates of the city to be left open, so that the nobles living in the countryside have easy access to his palace and party. We cannot contradict him.»

«Strengthen the guard on the walls!» cried the Captain, tapping a fist on the table to underline his order.

«Even here, I have my doubts as to whether I can do that. The Cardinal, for security purposes, wants most of the armed guards deployed around his palace.»

«The Cardinal, the Cardinal!» Guglielmo was going mad with rage and heat. «So we risk handing the city over to the enemy! So be it, but we will close all the gates of the city at dusk. We’ll leave only Porta St. Florian open, from where the noble laggards can easily reach Palazzo Baldeschi. We’ve never suffered assaults from the western part of the city. The enemy always assaults from the valley, coming from the Esino plain. It would be difficult for an army to come from the hills. Moreover, the western walls are very high and immediately inside Porta St. Florian we have a small fort with a bombard, to further defence. Prepare my steed, and call my son. It’s time to go: we’ll parade with the barded horses through the streets of the centre before we reach the Cardinal’s Palace.»

Roasts of the most varied variety of game, soups, salads and pastas, already in the late afternoon had been arranged on the large table where the guests would take their seats. The Cardinal held Lucia by the hand, while the servants sprayed the roasts, especially the cranes, peacocks and swans, with orange juice and rosewater, in order to make them more appetizing. The beef fillets, once boiled, were completely sprinkled with spices and sugar. Particular attention was paid to the side dishes, vegetables of all types and colours, which more than to be eaten, were used to cheer the eyes of diners and stimulate the appetite. In the soup tureens they showed off soups of various colours. The soups, which were usually served as desserts, had a sweet taste and were seasoned with sugar, saffron, pomegranate seeds and aromatic herbs. The real broth, prepared by boiling a mixture of meat, vegetables and spices in water, was used as a first course, especially in the countryside and in the castles of the peasant nobility. The broth was drunk while the meat, removed from the broth, was eaten separately and served with aromatic herbs. The Cardinal had ordered the cooks not to serve it, while he had instead cooked a novelty, originally from the court of Charles VIII, macaroni, obtained from wheat semolina shaped into vermicelli and seasoned in sauces made with olive oil, butter and cream. The desserts, apple and sponge cake, and fruit, apples, quinces, chestnuts, nuts and berries were placed on two separate tables. The wines in the jugs were those typical of the county, Verdicchio and Malvasìa. Only two jugs contained a red wine, a precious gift given to the Cardinal by the Grand Duke of Portonovo a few years before. On the dessert table, instead, the wine was that of sour cherry, from the countryside of Morro d’Alba.

«The guests will begin to arrive in a moment», said the Cardinal, addressing Lucia, finally freeing her from the grip of his icy hand. The young woman had never been able to understand why her uncle’s hands were always so cold, almost as if blood did not flow under his skin. Not even prolonged contact with her much warmer hand had been able to increase the temperature of Artemio’s. «Let’s go get ready.»

So saying, he retired to his rooms to get dressed in pomp and circumstance, while two young servants approached his niece. They would take her to the toilet, to devote themselves to her, first giving her a perfumed bath, then dressing her, and finally making her wear a sumptuous green silk gown. While she let herself be cared for, Lucia thought back to Andrea Franciolini’s eyes. And already! In those days she had inquired, and the handsome horseman whose eyes she had met only for a moment was her betrothed. And she had fallen in love with his eyes, his face, his poise, it was as if there had always been an alchemical affinity with him. She already felt him part of herself, part of her own soul, her whole body vibrated with the thought that soon she could talk to him, get to know him better, stare into his eyes, that they would certainly hide nothing from her. She looked out the window of the room, but felt a strange sensation: the sky of that long day that was turning into sunset was leaden. A hood of sultriness, of humidity, was gripping the city, instilling in her heart the feeling that something bad was going to happen in the short term, and that this something would also affect her in the long term. But what? She couldn’t understand it, even with her powers of vision. Her uncle’s mind, as usual, had also been hermetically sealed that day, but when she looked into his eyes only one word kept ringing in her head: “Betrayal”. Why? She wanted to make her sphere materialize, to throw it high into the sky so that she could see for her, but she couldn’t do that right now, in front of witnesses. While the tall blonde servant girl finished lacing her dress behind her back, the one with the smallest build and darkest hair made her wear the jewels, necklaces and bracelets of gold and precious stones, of exquisite workmanship, made by the Cardinal especially for her by goldsmiths of the school of Lucagnolo. At that moment, Lucia felt a lack, she felt a twinge in her heart as if someone was piercing it with a dagger, or with a sword. She collapsed in her chair and lost consciousness for a few moments.

«My lady, my lady, how do you feel?» The black maid’s voice came muffled to her ears.

«It’s nothing, it’s just the heat, this cursed heat, and the emotion. I feel better now.»

Lucia hadn’t associated her feeling with what would happen soon afterwards to her beloved Andrea.

Executor of the barbaric aggression of that day was the soldier of Francesco Maria Della Rovere, Duke of Montefeltro and already banner holder of the Church. Since the new Pope, Leo X, had stripped him of his state, he had hired Spanish and Gascon soldiers as mercenaries and, after having plundered many castles devoted to the Pope, he headed towards Jesi, in order to conquer this papal stronghold, with the help of the Ancona’s people led by the Duke of Montacuto and thanks to the secret support of the highest ecclesiastical office of the city, Cardinal Baldeschi. As promised by the Cardinal, the soldier coming from the hills west of Jesi, found Porta St. Florian open, had easy reason of the guards of the Fortino, attacked by surprise, and was soon in Piazza del Mercato, just when the procession of the nobleman Franciolini, coming from Via delle Botteghe, arrived in the same square.