полная версия

полная версияThe Emancipation of Massachusetts

The old world was passing away, a new era was opening, and a few words are due to that singular aristocracy which so long ruled New England. For two centuries Increase Mather has been extolled as an eminent example of the abilities and virtues which then adorned his order. In 1681, when all was over, he published a solemn statement of the attitude the clergy had held toward the Baptists, and from his words posterity may judge of their standard of morality and of truth.

“The Annabaptists in New England have in their narrative lately published, endeavoured to … make themselves the innocent persons and the Lord’s servants here no better than persecutors.... I have been a poor labourer in the Lord’s Vineyard in this place upward of twenty years; and it is more than I know, if in all that time, any of those that scruple infant baptism, have met with molestation from the magistrate merely on account of their opinion.” [Footnote: Preface to Ne Sutor.]

CHAPTER V. – THE QUAKERS

The lower the organism, the less would seem to be the capacity for physical adaptation to changed conditions of life; the jelly-fish dies in the aquarium, the dog has wandered throughout the world with his master. The same principle apparently holds true in the evolution of the intellect; for while the oyster lacks consciousness, the bee modifies the structure of its comb, and the swallow of her nest, to suit unforeseen contingencies, while the dog, the horse, and the elephant are capable of a high degree of education. [Footnote: Menial Evolution in Animals, Romanes, Am. ed. pp. 203-210.]

Applying this law to man, it will be found to be a fact that, whereas the barbarian is most tenacious of custom, the European can adopt new fashions with comparative ease. The obvious inference is, that in proportion as the brain is feeble it is incapable of the effort of origination; therefore, savages are the slaves of routine. Probably a stronger nervous system, or a peculiarity of environment, or both combined, served to excite impatience with their surroundings among the more favored races, from whence came a desire for innovation. And the mental flexibility thus slowly developed has passed by inheritance, and has been strengthened by use, until the tendency to vary, or think independently, has become an irrepressible instinct among some modern nations. Conservatism is the converse of variation, and as it springs from mental inertia it is always a progressively salient characteristic of each group in the descending scale. The Spaniard is less mutable than the Englishman, the Hindoo than the Spaniard, the Hottentot than the Hindoo, and the ape than the Hottentot. Therefore, a power whose existence depends upon the fixity of custom must be inimical to progress, but the authority of a sacred caste is altogether based upon an unreasoning reverence for tradition,—in short, on superstition; and as free inquiry is fatal to a belief in those fables which awed the childhood of the race, it has followed that established priesthoods have been almost uniformly the most conservative of social forces, and that clergymen have seldom failed to slay their variable brethren when opportunity has offered. History teems with such slaughters, some of the most instructive of which are related in the Old Testament, whose code of morals is purely theological.

Though there may be some question as to the strict veracity of the author of the Book of Kings, yet, as he was evidently a thorough churchman, there can be no doubt that he has faithfully preserved the traditions of the hierarchy; his chronicle therefore presents, as it were, a perfect mirror, wherein are reflected the workings of the ecclesiastical mind through many generations. According to his account, the theocracy only triumphed after a long and doubtful struggle. Samuel must have been an exceptionally able man, for, though he failed to control Saul, it was through his intrigues that David was enthroned, who was profoundly orthodox; yet Solomon lapsed again into heresy, and Jeroboam added to schism the even blacker crime of making “priests of the lowest of the people, which were not of the sons of Levi,” [Footnote: I Kings xii. 31.] and in consequence he has come down to posterity as the man who made Israel to sin. Ahab married Jezebel, who introduced the worship of Baal, and gave the support of government to a rival church. She therefore roused a hate which has made her immortal; but it was not until the reign of her son Jehoram that Elisha apparently felt strong enough to execute a plot he had made with one of the generals to precipitate a revolution, in which the whole of the house of Ahab should be murdered and the heretics exterminated. The awful story is told with wonderful power in the Bible.

“And Elisha the prophet called one of the children of the prophets, and said unto him, Gird up thy loins, and take this box of oil in thine hand, and go to Ramoth-gilead: and when thou comest thither, look out there Jehu, … and make him arise up … and carry him to an inner chamber; then take the box of oil, and pour it on his head, and say, Thus saith the Lord, I have anointed thee king over Israel....

“So the young man … went to Ramoth-gilead.... And he said, I have an errand to thee, O captain....

“And he arose, and went into the house; and he poured the oil on his head, and said unto him, Thus saith the Lord God of Israel, I have anointed thee king over the people of the Lord, even over Israel.

“And thou shalt smite the house of Ahab thy master, that I may avenge the blood of my servants the prophets....

“For the whole house of Ahab shall perish: … and I will make the house of Ahab like the house of Jeroboam the son of Nebat, … and the dogs shall eat Jezebel....

“Then Jehu came forth to the servants of his lord: … And he said, Thus spake he to me, saying, Thus saith the Lord, I have anointed thee king over Israel.

“Then they hasted, … and blew with trumpets, saying, Jehu is king. So Jehu … conspired against Joram....

“But king Joram was returned to be healed in Jezreel of the wounds which the Syrians had given him, when he fought with Hazael king of Syria....

“So Jehu rode in a chariot, and went to Jezreel; for Joram lay there....

“And Joram … went out … in his chariot, … against Jehu.... And it came to pass, when Joram saw Jehu, that he said, Is it peace, Jehu? And he answered, What peace, so long as the whoredoms of thy mother Jezebel and her witchcrafts are so many?

“And Joram turned his hands, and fled, and said to Ahaziah, There is treachery, O Ahaziah.

“And Jehu drew a bow with his full strength, and smote Jehoram between his arms, and the arrow went out at his heart, and he sunk down in his chariot....

“But when Ahaziah the king of Judah saw this, he fled by the way of the garden house. And Jehu followed after him, and said, Smite him also in the chariot. And they did so....

“And when Jehu was come to Jezreel, Jezebel heard of it; and she painted her face, and tired her head, and looked out at a window.

“And as Jehu entered in at the gate, she said, Had Zimri peace, who slew his master?…

“And he said, Throw her down. So they threw her down: and some of her blood was sprinkled on the wall, and on the horses: and he trod her under foot....

“And Ahab had seventy sons in Samaria. And Jehu wrote letters, … to the elders, and to them that brought up Ahab’s children, saying, … If ye be mine, … take ye the heads of … your master’s sons, and come to me to Jezreel by to-morrow this time.... And it came to pass, when the letter came to them, that they took the king’s sons, and slew seventy persons, and put their heads in baskets, and sent him them to Jezreel....

“And he said, Lay ye them in two heaps at the entering in of the gate until the morning....

“So Jehu slew all that remained of the house of Ahab in Jezreel, and all his great men, and his kinsfolks, and his priests, until he left him none remaining.

“And he arose and departed, and came to Samaria. And as he was at the shearing house in the way, Jehu met with the brethren of Ahaziah king of Judah....

“And he said, Take them alive. And they took them alive, and slew them at the pit of the shearing house, even two and forty men; neither left he any of them....

“And when he came to Samaria, he slew all that remained unto Ahab in Samaria, till he had destroyed him, according to the saying of the Lord, which he spake to Elijah.

“And Jehu gathered all the people together, and said unto them, Ahab served Baal a little; but Jehu shall serve him much. Now therefore call unto me all the prophets of Baal, all his servants, and all his priests; let none be wanting: for I have a great sacrifice to do to Baal; whosoever shall be wanting, he shall not live. But Jehu did it in subtilty, to the intent that he might destroy the worshippers of Baal....

“And Jehu sent through all Israel: and all the worshippers of Baal came, so that there was not a man left that came not. And they came into the house of Baal; and the house of Baal was full from one end to another....

“And it came to pass, as soon as he had made an end of offering the burnt offering, that Jehu said to the guard and to the captains, Go in, and slay them; let none come forth. And they smote them with the edge of the sword; and the guard and the captains cast them out....

“Thus Jehu destroyed Baal out of Israel.” [Footnote: 2 Kings ix., x.]

Viewed from the standpoint of comparative history, the policy of theocratic Massachusetts toward the Quakers was the necessary consequence of antecedent causes, and is exactly parallel with the massacre of the house of Ahab by Elisha and Jehu. The power of a dominant priesthood depended on conformity, and the Quakers absolutely refused to conform; nor was this the blackest of their crimes: they believed that the Deity communicated directly with men, and that these revelations were the highest rule of conduct. Manifestly such a doctrine was revolutionary. The influence of all ecclesiastics must ultimately rest upon the popular belief that they are endowed with attributes which are denied to common men. The syllogism of the New England elders was this: all revelation is contained in the Bible; we alone, from our peculiar education, are capable of interpreting the meaning of the Scriptures: therefore we only can declare the will of God. But it was evident that, were the dogma of “the inner light” once accepted, this reasoning must fall to the ground, and the authority of the ministry be overthrown. Necessarily those who held so subversive a doctrine would be pursued with greater hate than less harmful heretics, and thus contemplating the situation there is no difficulty in understanding why the Rev. John Wilson, pastor of Boston, should have vociferated in his pulpit, that “he would carry fire in one hand and faggots in the other, to burn all the Quakers in the world;” [Footnote: New England Judged, ed. 1703, p. 124.] why the Rev. John Higginson should have denounced the “inner light” as “a stinking vapour from hell;” [Footnote: Truth and Innocency Defended, ed. 1703, p. 80.] why the astute Norton should have taught that “the justice of God was the devil’s armour;” [Footnote: New England Judged, ed. 1703, p. 9.] and why Endicott sternly warned the first comers, “Take heed you break not our ecclesiastical laws, for then ye are sure to stretch by a halter.” [Footnote: Idem, p. 9.]

Nevertheless, this view has not commended itself to those learned clergymen who have been the chief historians of the Puritan commonwealth. They have, on the contrary, steadily maintained that the sectaries were the persecutors, since the company had exclusive ownership of the soil, and acted in self-defence.

The case of Roger Williams is thus summed up by Dr. Dexter: “In all strictness and honesty he persecuted them—not they him; just as the modern ‘Come-outer,’ who persistently intrudes his bad manners and pestering presence upon some private company, making himself, upon pretence of conscience, a nuisance there; is—if sane—the persecutor, rather than the man who forcibly assists, as well as courteously requires, his desired departure.” [Footnote: As to Roger Williams, p. 90.]

Dr. Ellis makes a similar argument regarding the Quakers: “It might appear as if good manners, and generosity and magnanimity of spirit, would have kept the Quakers away. Certainly, by every rule of right and reason, they ought to have kept away. They had no rights or business here.... Most clearly they courted persecution, suffering, and death; and, as the magistrates affirmed, ‘they rushed upon the sword.’ Those magistrates never intended them harm, … except as they believed that all their successive measures and sharper penalties were positively necessary to secure their jurisdiction from the wildest lawlessness and absolute anarchy.” [Footnote: Mass. and its Early History, p. 110] His conclusion is: “It is to be as frankly and positively affirmed that their Quaker tormentors were the aggressive party; that they wantonly initiated the strife, and with a dogged pertinacity persisted in outrages which drove the authorities almost to frenzy....” [Footnote: Idem, p. 104]

The proposition that the Congregationalists owned the territory granted by the charter of Charles I. as though it were a private estate, has been considered in an earlier chapter; and if the legal views there advanced are sound, it is incontrovertible, that all peaceful British subjects had a right to dwell in Massachusetts, provided they did not infringe the monopoly in trade. The only remaining question, therefore, is whether the Quakers were peaceful. Dr. Ellis, Dr. Palfrey, and Dr. Dexter have carefully collected a certain number of cases of misconduct, with the view of proving that the Friends were turbulent, and the government had reasonable grounds for apprehending such another outbreak as one which occurred a century before in Germany and is known as the Peasants’ War. Before, however, it is possible to enter upon a consideration of the evidence intelligently, it is necessary to fix the chronological order of the leading events of the persecution.

The twenty-one years over which it extended may be conveniently divided into three periods, of which the first began in July, 1656, when Mary Fisher and Anne Austin came to Boston, and lasted till December, 1661, when Charles II. interfered by commanding Endicott to send those under arrest to England for trial. Hitherto John Norton had been preeminent, but in that same December he was appointed on a mission to London, and as he died soon after his return, his direct influence on affairs then probably ceased. He had been chiefly responsible for the hangings of 1659 and 1660, but under no circumstances could they have been continued, for after four heretics had perished, it was found impossible to execute Wenlock Christison, who had been condemned, because of popular indignation.

Nevertheless, the respite was brief. In June, 1662, the king, in a letter confirming the charter, excluded the Quakers from the general toleration which he demanded for other sects, and the old legislation was forthwith revived; only as it was found impossible to kill the schismatics openly, the inference, from what occurred subsequently, is unavoidable, that the elders sought to attain their purpose by what their reverend historians call “a humaner policy,” [Footnote: As to Roger Williams, p. 134.] or, in plain English, by murdering them by flogging and starvation. Nor was the device new, for the same stratagem had already been resorted to by the East India Company, in Hindostan, before they were granted full criminal jurisdiction. [Footnote: Mill’s British India, i. 48, note.]

The Vagabond Act was too well contrived for compassing such an end, to have been an accident, and portions of it strongly suggest the hand of Norton. It was passed in May, 1661, when it was becoming evident that hanging must be abandoned, and its provisions can only be explained on the supposition that it was the intention to make the infliction of death discretionary with each magistrate. It provided that any foreign Quaker, or any native upon a second conviction, might be ordered to receive an unlimited number of stripes. It is important also to observe that the whip was a two-handed implement, armed with lashes made of twisted and knotted cord or catgut. [Footnote: New England Judged, ed. 1703, p. 357, note.] There can be no doubt, moreover, that sundry of the judgments afterward pronounced would have resulted fatally had the people permitted their execution. During the autumn following its enactment this statute was suspended, but it was revived in about ten months.

Endicott’s death in 1665 marks the close of the second epoch, and ten comparatively tranquil years followed. Bellingham’s moderation may have been in part due to the interference of the royal commissioners, but a more potent reason was the popular disgust, which had become so strong that the penal laws could not be enforced.

A last effort was made to rekindle the dying flame in 1675, by fining constables who failed in their duty to break up Quaker meetings, and offering one third of the penalty to the informer. Magistrates were required to sentence those apprehended to the House of Correction, where they were to be kept three days on bread and water, and whipped. [Footnote: Mass. Rec. v. 60.] Several suffered during this revival, the last of whom was Margaret Brewster. At the end of twenty-one years the policy of cruelty had become thoroughly discredited and a general toleration could no longer be postponed; but this great liberal triumph was only won by heroic courage and by the endurance of excruciating torments. Marmaduke Stevenson, William Robinson, Mary Dyer, and William Leddra were hanged, several were mutilated or branded, two at least are known to have died from starvation and whipping, and it is probable that others were killed whose fate cannot be traced. The number tortured under the Vagabond Act is unknown, nor can any estimate be made of the misery inflicted upon children by the ruin and exile of parents.

The early Quakers were enthusiasts, and therefore occasionally spoke and acted extravagantly; they also adopted some offensive customs, the most objectionable of which was wearing the hat; all this is immaterial. The question at issue is not their social attractiveness, but the cause whose consequence was a virulent persecution. This can only be determined by an analysis of the evidence. If, upon an impartial review of the cases of outrage which have been collected, it shall appear probable that the conduct of the Friends was sufficiently violent to make it credible that the legislature spoke the truth, when it declared that “the prudence of this court was exercised onely in making provission to secure the peace & order heere established against theire attempts, whose designe (wee were well assured by our oune experjence, as well as by the example of theire predecessors in Munster) was to vndermine & ruine the same;” [Footnote: Mass. Rec. vol. iv. pt. 1, p. 385.] then the reverend historians of the theocracy must be considered to have established their proposition. But if, on the other hand, it shall seem apparent that the intense vindictiveness of this onslaught was due to the bigotry and greed of power of a despotic priesthood, who saw in the spread of independent thought a menace to the ascendency of their order, then it must be held to be demonstrated that the clergy of New England acted in obedience to those natural laws, which have always regulated the conduct of mankind.

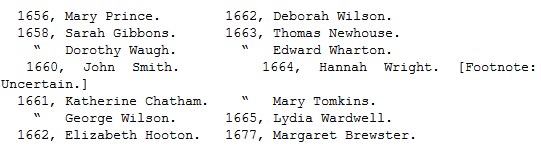

CHRONOLOGY.

1656, July. First Quakers came to Boston.

1656, 14 Oct. First act against Quakers passed. Providing that ship-masters bringing Quakers should be fined £100. Quakers to be whipped and imprisoned till expelled. Importers of Quaker books to be fined. Any defending Quaker opinions to be fined, first offence, 40s.; second, £4; third, banishment.

1657, 14 Oct. By a supplementary act; Quakers returning after one conviction for first offence, for men, loss of one ear; imprisonment till exile. Second offence, loss other ear, like imprisonment. For females; first offence, whipping, imprisonment. Second offence, idem. Third offence, men and women alike; tongue to be bored with a hot iron, imprisonment, exile. [Footnote: Mass. Rec. vol. iv. pt. 1, p. 309.]

1658. In this year Rev. John Norton actively exerted himself to secure more stringent legislation; procured petition to that effect to be presented to court.

1658, 19 Oct. Enacted that undomiciled Quakers returning from banishment should be hanged. Domiciled Quakers upon conviction, refusing to apostatize, to be banished, under pain of death on return. [Footnote: Idem, p. 346.]

Under this act the following persons were hanged:

1659, 27 Oct. Robinson and Stevenson hanged.

1660, 1 June. Mary Dyer hanged. (Previously condemned, reprieved, and executed for returning.)

1660-1661, 14 Mar. William Leddra hanged.

1661, June. Wenlock Christison condemned to death; released.

1661, 22 May. Vagabond Act. Any person convicted before a county magistrate of being an undomiciled or vagabond Quaker to be stripped naked to the middle, tied to the cart’s tail, and flogged from town to town to the border. Domiciled Quakers to be proceeded against under Act of 1658 to banishment, and then treated as vagabond Quakers. The death penalty was still preserved but not enforced. [Footnote: Mass. Rec. vol. iv. pt. 2, p. 3.]

1661, 9 Sept. King Charles II. wrote to Governor Endicott directing the cessation of corporal punishment in regard to Quakers, and ordering the accused to be sent to England for trial.

1661. 27 Nov. Vagabond Act suspended.

1662. 28 June. The company’s agents, Bradstreet and Norton, received from the king his letter of pardon, etc., wherein, however, Quakers are excepted from the demand made for religious toleration.

1662, 8 Oct. Encouraged by the above letter the Vagabond law revived.

1664-5, 15 March. Death of John Endicott. Bellingham governor. Commissioners interfere on behalf of Quakers in May. The persecution subsides.

1672, 3 Nov. Persecution revived by passage of law punishing persons found at Quaker meeting by fine or imprisonment and flogging. Also fining constables for neglect in making arrests and giving one third the fine to informers. [Footnote: Mass. Rec. v. 60.]

1677, Aug. 9. Margaret Brewster whipped for entering the Old South in sackcloth.

TURBULENT QUAKERS

“It was in the month called July, of this present year [1656] when Mary Fisher and Ann Austin arrived in the road before Boston, before ever a law was made there against the Quakers; and yet they were very ill treated; for before they came ashore, the deputy governor, Richard Bellingham (the governor himself being out of town) sent officers aboard, who searched their trunks and chests, and took away the books they found there, which were about one hundred, and carried them ashore, after having commanded the said women to be kept prisoners aboard; and the said books were, by an order of the council, burnt in the market-place by the hangman.... And then they were shut up close prisoners, and command was given that none should come to them without leave; a fine of five pounds being laid on any that should otherwise come at, or speak with them, tho’ but at the window. Their pens, ink, and paper were taken from them, and they not suffered to have any candle-light in the night season; nay, what is more, they were stript naked, under pretence to know whether they were witches [a true touch of sacerdotal malignity] tho’ in searching no token was found upon them but of innocence. And in this search they were so barbarously misused that modesty forbids to mention it: And that none might have communication with them a board was nailed up before the window of the jail. And seeing they were not provided with victuals, Nicholas Upshal, one who had lived long in Boston, and was a member of the church there, was so concerned about it, (liberty being denied to send them provision) that he purchased it of the jailor at the rate of five shillings a week, lest they should have starved. And after having been about five weeks prisoners, William Chichester, master of a vessel, was bound in one hundred pound bond to carry them back, and not suffer any to speak with them, after they were put on board; and the jailor kept their beds … and their Bible, for his fees.” [Footnote: Sewel, p. 160.]